Encyclopedia of Drugs, Alcohol, and Addictive Behavior 2Nd Ed Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progressive-Era Hygienic Ideology, Waste, and Upton Sinclair's the Jungle

Processes of Elimination: Progressive-Era Hygienic Ideology, Waste, and Upton Sinclair's The Jungle J. Michael Duvall Disappointed that The Jungle did not result in a ground-swell of socialist sentiment, Upton Sinclair famously evaluated his best-known novel as a kind of failure. "I aimed at the public's heart," he wrote, "and by accident hit them in the stomach."1 Yet no one could doubt that Sinclair aimed at the public's heart, given The Jungle's sentimentality, but the idea that he hit the public in the stomach by accident obviously overstates the case. More likely, Sinclair aimed at the public's stomach, but hoped that the blow would cause moral outrage and a lasting change in the public's heart. He was following a venerable recipe for fomenting moral judgment: begin with your basic jeremiad, ladle in liberal amounts of the filthy and the revolting, and stir.2 As William Ian Miller affirms in The Anatomy of Disgust, Sinclair's gambit is right on target. Disgust and moral judgment are nearly always wrapped up together, for "except for the highest-toned discourses of moral philosophers, moral judgment seems almost to demand the idiom of disgust. That makes me sick! What revolting behavior! You give me the creeps!'3 Miller's illustration of how disgust surfaces in expressions of moral judgment highlights that disgust is encoded bodily. This is evidenced in the adjectives "sick" and "revolting" and the noun "the creeps," all three quite visceral in their tone and implications. Invoking the disgusting is but one way in which The Jungle enlists the body, in this case, the bodies of readers themselves. -

Iuscholarworks Dr. Ruth Clifford Engs Presentations, Publications

Indiana University Bloomington IUScholarWorks Dr. Ruth Clifford Engs Presentations, Publications & Research Data Collection Citation for this item To obtain the citation format and information for this document go to: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/17143 The Collection This document is part of a collection that serves two purposes. First, it is a digital archive for a sampling of unpublished documents, presentations, questionnaires and limited publications resulting from over forty years of research. Second, it is a public archive for data on college student drinking patterns on the national and international level collected for over 20 years. Research topics by Dr. Engs have included the exploration of hypotheses concerning the determinants of behaviors such as student drinking patterns; models that have examine the etiology of cycles of prohibition and temperance movements, origins of western European drinking cultures (attitudes and behaviors concerning alcohol) from antiquity, eugenics, Progressive Era, and other social reform movements with moral overtones-Clean Living Movements; biographies of health and social reformers including Upton Sinclair; and oral histories of elderly monks. This collection is found at IUScholarWorks: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/16829 Indiana University Archives Paper manuscripts and material for Dr. Engs can be found in the IUArchives http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/findingaids/view?doc.view=entire_text&docId=InU-Ar- VAC0859 1 Engs- American Cycles of Prohibition. Paper presented: Kettil Bruun Annual meeting. June 2. 1992. AMERICAN CYCLES OF PROHIBITION: DO THEY HAVE ROOTS IN ANCIENT DRINKING NORMS ? Ruth C. Engs, Professor. Applied Health Science, HPER 116, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405. Paper Presented: Kettil Bruun Society's Alcohol Epidemiology Meeting. -

Dr. Ruth C(Lifford) Engs - Presentations, Publications & Research Data Collection

Indiana University Bloomington IUScholarWorks Citation for this item Citation format and information for this document is found at: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/17484 This paper is from: Dr. Ruth C(lifford) Engs - Presentations, Publications & Research Data Collection. This collection is found at IUScholarWorks: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/16829 When in the collection and within a category, click on “title” to see all items in alphabetical order. The Collection This document is part of a collection that serves two purposes. First, it is a digital archive for a sampling of unpublished documents, presentations, questionnaires and limited publications resulting from over forty years of research. Second, it is a public archive for data on college student drinking patterns on the national and international level collected for over 20 years. Research topics by Dr. Engs have included the exploration of hypotheses concerning the determinants of behaviors such as student drinking patterns; models that have examine the etiology of cycles of prohibition and temperance movements, origins of western European drinking cultures (attitudes and behaviors concerning alcohol) from antiquity, eugenics, Progressive Era, and other social reform movements with moral overtones-Clean Living Movements; biographies of health and social reformers including Upton Sinclair; and oral histories of elderly monks. Indiana University Archives Paper manuscripts and material for Dr. Engs can be found in the IUArchives http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/findingaids/view?doc.view=entire_text&docId=InU-Ar-VAC0859 Journal of School Health • April 1991, Vol. 61, No. 4 Resurgence of a New "Clean Living" Movement in the United States Ruth C. Engs ABSTRACT During the late 19th century, a "clean living" movement emerged in the U.S. -

Eugenics, Immigration Restriction and Birth Control

Engs, Ruth Clifford (2014). Eugenics, Immigration Restriction and the Birth Control Movements. In: Katherine A.S. Sibley (ed.), A Companion to Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. Wiley Online Library: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Retrieved from IUScholarworks repository at: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/19003. Complete book available at Wiley Online Library: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/book/10.1002/9781118834510 NOTE: Paper manuscripts and material for Dr. Engs can be found in the IUArchives. Finding aid for collection is available at: http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/findingaids/view?doc.view=entire_text&docId=InU-Ar-VAC085 Information for this and similar works found on: http://alcohol.iu.edu - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - Chapter 16: EUGENICS, IMMIGRATION RESTRICTION AND THE BIRTH CONTROL MOVEMENTS Ruth Clifford Engs ABSTRACT: Agitation for eugenics, immigration restriction, and birth control were intertwined during the first decades of the twentieth century along with numerous other health issues. Campaigns for these causes led to public policies in an effort to improve the physical, mental and social health of the nation. However, these issues were not considered of historical interest until the post-World War II era. Eugenics and the leaders of the eugenics movement were often discredited by late twentieth-century historians as elitists or racists, while early immigration restriction laws and nativism gained renewed interest, and birth control and its early leaders such as Margaret Sanger were both eulogized and demonized. Contested interpretations of all three of these reform movements and their leaders have been found since the 1950s. BACKGROUND INFORMATION The importance of the “rights of society” versus “the rights of the individual” goes in and out of fashion. -

Thesis of Painted Women and Patrons

THESIS OF PAINTED WOMEN AND PATRONS: AN ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL ITEMS AND IDENTITY AT A VICTORIAN-ERA RED LIGHT DISTRICT IN OURAY, COLORADO Submitted by Kristin A. Gensmer Department of Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2012 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Mary Van Buren Linda Carlson Lynn Kwiatkowski Copyright by Kristin A. Gensmer 2012 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT OF PAINTED WOMEN AND PATRONS: AN ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL ITEMS AND IDENTITY AT A VICTORIAN-ERA RED LIGHT DISTRICT IN OURAY, COLORADO Archaeological investigations of prostitution tend to focus on identifying the presence of females in male spaces and differentiating brothel assemblages from surrounding households. These approaches often focus on upper-class establishments and define prostitutes solely by their labor. Additionally, these scholars neglect the fact that prostitution could not exist without customers. Although often ignored, personal items represent one of the few means of addressing such oversights. In this thesis, I analyze a sample of 948 personal items recovered from the Vanoli Site (5OR30) in conjunction with data gleaned from historic documents including censuses and photographs in order to discuss Victorian-era prostitution in Ouray, Colorado. This project was designed to 1) explore the premise that the prostitute was a performative identity constructed through the manipulation of clothing, accessories, cosmetics, and hygiene by sex workers as part of their work; 2) examine the similarities between prostitutes and other working- class women in Ouray, 3) provide information about the otherwise invisible customers. The personal items and documentary evidence indicate that women and men on the Vanoli block were presenting a clean, well-groomed, and thoroughly working-class appearance. -

This Outline and Bibliography Are Found on the Oncourse Web Site for This Course

OUTLINE FOR THE HISTORY OF PUBLIC HEALTH LECTURE SPH 505 Dr. Ruth Clifford Engs, Professor Emerita, Department of Applied Health Science, School of Public Health, Bloomington, IN. email: [email protected] Webpage: www.indiana.edu/~engs/ IUScholarworks permanent repository webpage: https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/handle/2022/16829/browse?type=title This outline and bibliography are found on the Oncourse web site for this course. They can also be accessed at any time at: www.indiana.edu/~engs/alectures.shtml INTRODUCTION TO THE OUTLINE Objective: the purpose of these lectures is to present an overview of the history, and to some extent the historiography of public health, and its many entities over the centuries-- particularly from the mid-19th century-- so as to gain insight into the depth and breadth of our discipline. Background: The foundation of modern public health in western society emerged out of the mid-19th and early 20th centuries. Various fields of interest and concern often intertwined and overlapped in this era. These different aspects of public health including hygiene, preventive medicine, environmental concerns, physiology, physical and recreational activities and research diverged over the twentieth century into seemingly separate fields of study and practice. We have now come back together in the early twenty-first century under one public health umbrella. The history of anything is based upon perceptions which may, or may not, be what actually occurred. An historian interprets the event based upon primary sources which include original documents, eyewitness reports, or artifacts. For example, field notes of the number of head injuries of high school football players with certain type of helmet in 1982 in Bloomington, IN or a diary or letters about the cholera epidemic and the weather summer 1832 in Boston. -

Chapter One: Introduction

Engs, Ruth Clifford. Clean Living Movements: American Cycles of Health Reform. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2001 Chapter One: Introduction There is a tide in the affairs of men, with flood and ebb, we will admit readily enough. Luther Gulick, World=s Work (1908) When the moment is ripe, only the fanatic can hatch a genuine mass movement. Eric Hoffer, The True Believer (1951) American reform has come in waves, with a decade or more of intense activity followed by periods of relative apathy about social problems. Ronald G. Walters, American Reformers 1815-1860 (1978) The chief function...of physical exercise, is to establish habits of clean living, health and stamina on a permanent basis [italics mine]. William Hemmingway, Harper=s Weekly (1913) Since colonial times, four AGreat Awakenings@ have occurred in the United States. These social movements have typically begun with religious revivals from which significant political, economic, and social changes emerged. William G. McLoughlin (1978, xiii), a religious historian, in his Revivals, Awakenings, and Reform, has defined awakenings as Aperiods of cultural revitalization that begin in a general crisis of beliefs and values and extend over a period of a generation or so during which time a profound reorientation in beliefs and values takes place. Revivals alter the lives of individuals; awakenings alter the world-view of a whole people or culture.@ These awakenings have come in roughly eighty-to one hundred- year cycles.1 James Q. Wilson (1980, 29-30) has argued that Great Awakenings occur at 1 Engs - Clean Living ch. 1 This chapterl from final draft. Please check hard copy of book for quotations for use in any publications. -

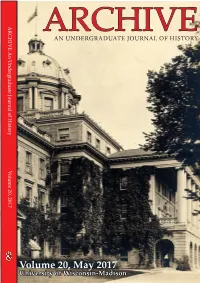

ARCHIVE – Volume 20

ARCHIVE An Undergraduate Journal of History of Journal Undergraduate An ARCHIVE ARCHIVEAN UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF HISTORY Volume 20, 2017 Volume Volume 20, May 2017 University of Wisconsin-Madison VOLUME 20, MAY 2017 AN UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF HISTORY ARCHIVE An interdisciplinary journal featuring undergraduate work in history and related fields, founded in 1998. Editor-In-Chief Maren Harris Editorial Board David Clerkin Isaac Mehlhaff Hilary Miller Rachel Pope Lucas Sczygelski Madeline Sweitzer Connor Touhey Emma Wathen Faculty Advisor Professor Sarah Thal Published by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Printing services provided by DoIt Digital Publishing COVER IMAGE This photo shows a side view of Bascom Hall from the southeast, taken after the portico was remodeled in 1895 but before the dome burned on October 10, 1916. Image courtesy of University of Wisconsin-Madison Digital Collections. CONTENTS HINDENBERG V. S CHURZ How Wisconsin’s German Americans Helped Defeat American Nazism 7 Kyle Watter BABY OR THE BOTTLE Effects of Social Movements on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in the United States 21 Hannah Teller THEOLOGY AS AN INSTRUMENT FOR CHANGE Religious Revival and Abolitionist Sentiment in 18th-Century Connecticut 41 Alexandra Aaron SINCE YOU WENT AWay The Gendered Experience in World War II Letters 55 Emma Sayner ALCOHOL AND SOCIALIZation IN SLAVE SOCIETIES OF THE NEW WORLD 73 Luke Voegeli HOW STEREOTYPES SHAPED AN EPIDEMIC The Co-Occurence of HIV and Mental Illness 97 Marissa Korte FEEDING ON EMPIRES Piracy in the South China Sea at the Turn of the 19th Century 121 Lezhi Wang BASEBALL BEHIND A MASK Jews, African Americans, and Identity On and Off the Baseball Field 141 Ben Pickman NEW YORK’S MUNICIPAL Health CRISIS The Creation of the Health and Hospitals Corporation 169 Hanan Lane A NOTE FROM THE EDITORS The 2017 Editorial Board is proud to present the 20th edition of ARCHIVE. -

William Banting and Bantingism: a Cultural History of a Victorian Anti-Fat Aesthetic Jaime Michelle Miller Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Theses & Dissertations English Summer 2014 "Do You Bant?" William Banting and Bantingism: A Cultural History of a Victorian Anti-Fat Aesthetic Jaime Michelle Miller Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the European History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Jaime M.. ""Do You Bant?" William Banting and Bantingism: A Cultural History of a Victorian Anti-Fat Aesthetic" (2014). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, English, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/xda4-7y41 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds/59 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DO YOU BANT?” WILLIAM BANTING AND BANTINGISM: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF A VICTORIAN ANTI-FAT AESTHETIC by Jaime Michelle Miller B.A. May 2000, The College of William and Mary M.A. August 2002, Old Dominion University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ENGLISH OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2014 ved by: Imtiaz HacihJDfrefctor) Manuela Mourao (Member) UMI Number: 3662236 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

The Sociological Roots of Eugenics Demographic, Ethnographic and Educational Solutions to the Racial Crises in Progressive America

The Sociological Roots of Eugenics Demographic, Ethnographic and Educational Solutions to the Racial Crises in Progressive America Michael Kohlman Editor’s note: This paper is adapted from “The An- Introduction thropology of Eugenics in America: Ethnographic, Race-Hygiene and Human Geography Solutions to My current research primarily explores the educa- the Great Crises of Progressive America,” first pub- tional programs and impacts of the eugenics move- lished in the Alberta Science Education Journal, ment in North America from its Progressive Era as- volume 42, number 2. cent through its purported rapid decline after World War II. Eugenics education was a top priority for the disciples of Sir Francis Galton, the celebrated founder Abstract of the “science of race-betterment.” In America, the seminal ideas of Galton and other pioneers combined This paper explores the directors, popularizers and with pre-existing Nativist or Nordic biases and prior educators of the sociological aspects of the American strains of scientific racism, such as Samuel Morton eugenics movement in the Progressive Era. Human and the American School of Anthropology. In the first geography (especially the fledgling discipline of half of the “American Century,” public eugenics demography), sociobiology (human fertility and so- education for the burgeoning middle classes and cial hygiene) and ethnology (pedigree studies and professional groups, and formal courses for future racial characteristics) were considered important generations who would inherit the onus of “racial “roots”’ of the “tree” of the applied science of eugen- civic duty” were both seen as vital to the success of ics (see Figure 1). This essay concentrates on a few the movement. -

2018 Finkelstein Alexander Th

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ROAD POWER: THE POLITICS OF AMERICAN HIGHWAY DEVELOPMENT, 1900-1939 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By ALEXANDER FINKELSTEIN Norman, Oklahoma 2018 ROAD POWER: THE POLITICS OF AMERICAN HIGHWAY DEVELOPMENT, 1900-1939 A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY _______________________________ Dr. David Wrobel, Chair _______________________________ Dr. Kathleen Brosnan _______________________________ Dr. Anne Hyde © Copyright by ALEXANDER FINKELSTEIN 2018 All Rights Reserved. iv Acknowledgements Writing a thesis is no easy task, but the people around me have made the process smooth, meaningful, and, enjoyable. I am eternally grateful to my thesis committee for engaging with me and helping me mature as a person and scholar. David Wrobel ensured I never lost sight of my goal or the bigger picture. I am indebted to him for the continuous advice and his willingness to engage with my many (and oftentimes unwieldy) drafts. Kathleen Brosnan taught me how to express my ideas clearly and probe my ideas for deeper meaning. Though this is perhaps not the shortest thesis ever produced, “concision and precision” has and will continue to guide my writing. Anne Hyde helped make the transition to graduate school as seamless as possible. I thank her for always being willing to bounce ideas off of and reminding me to remember the human aspect of the story. Beyond Drs. Wrobel, Brosnan, and Hyde, I have found a community at the University of Oklahoma of my fellow graduate students and the professors that have unceasingly continued to push me to grow and work harder. -

Engs - Presentations, Publications & Research Data Collection

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUScholarWorks Indiana University Bloomington IUScholarWorks Citation for this item Citation format and information for this document is found at: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/18504 This paper is from: Dr. Ruth C(lifford) Engs - Presentations, Publications & Research Data Collection. This collection is found at IUScholarWorks: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/16829 When in the collection and within a category, click on “title” to see all items in alphabetical order. The Collection This document is part of a collection that serves two purposes. First, it is a digital archive for a sampling of unpublished documents, presentations, questionnaires and limited publications resulting from over forty years of research. Second, it is a public archive for data on college student drinking patterns on the national and international level collected for over 20 years. Research topics by Dr. Engs have included the exploration of hypotheses concerning the determinants of behaviors such as student drinking patterns; models that have examine the etiology of cycles of prohibition and temperance movements, origins of western European drinking cultures (attitudes and behaviors concerning alcohol) from antiquity, eugenics, Progressive Era, and other social reform movements with moral overtones-Clean Living Movements; biographies of health and social reformers including Upton Sinclair; and oral histories of elderly monks. Indiana University Archives Paper manuscripts and material for Dr. Engs can be found in the IUArchives http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/findingaids/view?doc.view=entire_text&docId=InU-Ar- VAC0859 1 Engs- history of public health OUTLINE FOR LECTURES ON “THE HISTORY OF PUBLIC HEALTH”1 Dr.