Documenting Wallenberg. a Compilation of Interviews With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numero 8, Junio–Julio 2018 Al La Tuta

Numero 8, Junio–Julio 2018 Al la tuta mondo: Bonvenon al la verda Gotenburgo ! Bonvolu viziti nian retpaĝon: www.esperanto-gbg.org Enhavo Paĝo 2. Enhavo. 17. Senlime en Kungahälla. Pri Ora Ĵurnalo. Kungahälla. 3. Espeporko informas. Oriente ĉe la rivero. Sommardagar i Göteborg – pröva en 18. Klosterkullen. intensivkurs i Esperanto 2018. ”Konungahælla Ytri”. 4. Esperanto ĉe la Roskilde-festivalo. 19. Ragnhildsholmen. Esperantofestival den 13–19 juli på La trireĝa renkontiĝo. Esperanto-Gården och Folkets Hus i 20. Upupo. Lesjöfors, Värmland. Vortludo de Monica Eissing. Somera programo en Grésillon. Anekdoto (el 1904). 5. Valdemar Langlet – forgesita heroo. 21. Pentekosto en la preĝejo de Angered. 6. Paret Langlet. 22. En vänlig grönskas rika dräkt. Ps. 201. 7. Skandinava Esperanto-kongreso memore 23. La 100-jara jubileo de la unua landa al la unua Skandinava kongreso, kiu kunveno de la sameoj. okazis 1918 en Gotenburgo. 24. Svenska teckenspråkets dag – La tago de 8. La jarkunsido de SEF sur la ŝipo Pearl la sveda signolingvo, 14 majo. Seaways, la 11an de majo. 25. Gejunuloj el Ukrainio vizitis Goteburgon. 9. Ana Cumbelic Rössum – interparolo sur 26. ”Esperanto – ett påhitt”. la ŝipo. Vad säger de om esperanto på Twitter? 10. Pliaj renkontoj sur la ŝipo. 27. Kia estas averaĝa Esperantisto? 11. Jens Larsen – ĉiĉeronis nin en 28. Kresko – Ora Ĵurnalos motsvarighet i Kopenhago. Kroatien. El ”Finaj vortoj” de Jens Larsen post la Recenzo de ”Adam Smith – vivo kaj ĉiĉeronado. verko” de Bo Sandelin. 13. Tri interesaj prelegantoj el Norvegio. 29. Miljöpartiet och esperanto. 14. En la katedralo Karl Johan en Oslo. Esperantista verkisto kiel kandidato por Debato en la revuo NU (liberala) 24an de la Nobel-Premio pri literaturo? majo 2018. -

Gratuities Gratuities Are Not Included in Your Tour Price and Are at Your Own Discretion

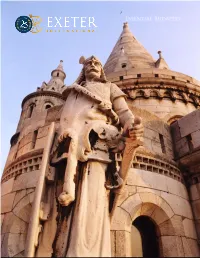

Upon arrival into Budapest, you will be met and privately transferred to your hotel in central Budapest. On the way to the hotel, you will pass by sights of historical significance, including St. Stephen’s Basilica, a cross between Neo-Classical and Renaissance-style architecture completed in the late 19th century and one of Budapest’s noteworthy landmarks. Over the centuries, Budapest flourished as a crossroads where East meets West in the heart of Europe. Ancient cultures, such as the Magyars, the Mongols, and the Turks, have all left an indelible mark on this magical city. Buda and Pest, separated by the Danube River, are characterized by an assortment of monuments, elegant streets, wine taverns, coffee houses, and Turkish baths. Arrival Transfer Four Seasons Gresham Palace This morning, after meeting your driver and guide in the hotel lobby, drive along the Danube to see the imposing hills of Buda and catch a glimpse of the Budapest Royal Palace. If you like, today you can stop at the moving memorial of the Shoes on the Danube Promenade. Located near the parliament, this memorial honors the Jews who fell victim to the fascist militiamen during WWII. Then drive across the lovely 19th-century Chain Bridge to the Budapest Funicular (vertical rail car), which will take you up the side of Buda’s historic Royal Palace, the former Hapsburg palace during the 19th century and rebuilt in the Neo-Classical style after it was destroyed during World War II. Today the castle holds the Hungarian National Gallery, featuring the best of Hungarian art. -

The Wallenberg Affair and the Onset of the Cold War

REVIEW ESSAY The Wallenberg Affair and the Onset of the Cold War ✣ Marvin W. Makinen Stefan Karner, ed., Auf den Spuren Wallenbergs. Innsbruck: Studien Verlag, 2015. 200 pp. €24.90. This book contains revised versions of essays about Raoul Wallenberg orig- inally presented at a conference in mid-November 2012 at the Diplomatic Academy in Vienna, organized by Stefan Karner, the director of the Ludwig Boltzmann-Institut für Kriegsfolgen-Forschung, in Graz, Austria. The con- ference was one of many events around the world that marked Wallenberg’s 100th birthday and was held with the intention of bringing together interna- tionally known researchers who have worked on the history of Wallenberg’s activities in the closing months of World War II in Budapest, as well as re- searchers who have tried to bring clarity to his fate in Soviet captivity. Karner is known for his historical research on Austrians who served in the German army during World War II and were arrested as prisoners-of-war in the So- viet Union and of Austrians arrested in Soviet-occupied Austria after World War II. The book consists of contributions written originally in English or in German, in addition to contributions prepared originally in Russian and then translated into German. Presentation of research reports either in English or in German may limit not only the general readership of the book but also that of many individuals who have maintained interest in the subject or have followed its development over many decades. Considering that some contri- butions were translated from Russian into German, it is surprising that the entire book was not published in one language, either English or German. -

The Hungarian Economic “Renaissance”, Shows The

HUNGARIAN NATIONAL TRADING HOUSE STATE SECR. ECONOMIC DIPLOMACY Innovative solutions of high How Hungary specialization in frontline successfully dealt sectors p. 8-9 with the crisis p. 5 HUNGARY Supplement in Leaps in Growth Sunday 4 December 2016 ABOUT HUNGARY Hungarian Rhapsody... The Hungarian economic History, arts, sciences, inventions, great achievements of the past and present. “renaissance”, shows the way An impressive mixture creates the profile of a historic nation. p. 3 The country that leads the way to economic growth in Europe in recent years. STUDYING IN HUNGARY By changing their decade-long mentality in a short economy, particular emphasis was placed in encour- time, Hungarians managed to turn a statism-type aging foreign investments, mainly through incentives. The crucial role of education economy with watertight structures of the eastern Hungary, as a member of the European Union has block, into a market economy. The country, with created a favorable institutional framework that of- in development a midsize -for European standards- economy, fers substantial incentives to domestic and especially based itself mainly on heavy industry, while the foreign investors. The latter have contributed to the The diplomas awarded by Hungarian universities sector of services has played a significant role economy more than $ 92 billion in direct foreign in- have a worldwide high prestige, while foreign in the ongoing development, which contributed vestments since 1989. language courses are of high quality, with very more than 60% to the GDP of the country. affordable -or even zero- tuition. To speed up Hungary’s transition to a market p. 4 p. 12 Building bridges between THE HUNGARIAN TOURISM An important growth Greece and Hungary engine for Hungary The medium-term prospects of the Greek The Hungarian economy is growing multidimen- sionally, utilizing all the areas that can contribute market, have sparked the interest of to the overall GDP. -

La Place De L'helvète : Considérations Sur Un Vivant Qui Passe

RubriqueUn vivant cinéma qui suissepasse 77 Un vivant qui passe La place de l’Helvète : Considérations sur Un vivant qui passe 1 Le cinéma « alternatif » Spoutnik, à Genève, l’a montré en septembre 2001. par Alain Freudiger 2 Cette phrase d’un discours de Jean-Pascal Delamuraz, alors président de la Confédéra- tion, prononcée en 199 avait été relevée par l’écrivain Adolf Muschg dans un essai intitulé « Wenn Auschwitz in der Schweiz liegt », paru en Réalisé par Claude Lanzmann en 1997, Un vivant qui passe n’a jamais été français peu après. Voir Adolf Muschg, Cinq dis- 1 cours d’un Suisse à sa nation qui n’en est pas projeté en Suisse – à une exception notable . Cela est d’autant plus sur- une, Ed. Zoé, Genève, 199. prenant que, outre l’importance majeure de Lanzmann comme réalisa- 3 « Dr Rossel : mais ils avaient l’impression de teur depuis Shoah (1985), ce film touche à des questions particulièrement faire quelque chose d’utile. C’est l’impression cruciales pour la Suisse : la neutralité, la Croix Rouge, l’humanitaire, la que ça donnait, parce que, si on leur parlait des non-implication… Il est possible que personne n’ait souhaité program- camps, des prisonniers, des détenus, quoi, et des choses comme ça, ils disaient : ‹ Oui, mais mer ce film à sa sortie, puisque la Suisse était alors empêtrée dans la crise enfin, l’Allemagne fait maintenant, ici, un travail des fonds en déshérence. Pourtant, il constitue une excellente réponse invraisemblable, extraordinaire, dont toute l’Eu- rope nous sera reconnaissante. › » Claude Lanz- au trop fameux « Auschwitz, ce n’est quand même pas en Suisse ! » de mann, Un vivant qui passe. -

January 2011 Angelo Roncalli (John XXIII) Synopsis of Documents

January 2011 Angelo Roncalli (John XXIII) Synopsis of Documents Introduction: When reviewing Angelo Roncalli's activities in favor of the Jewish people across many years, one may distinguish three parts; the first, during the years 1940-1944, when he served as Apostolic Delegate of the Vatican in Istanbul, Turkey, with responsibility over the Balkan region. The second, as a Nuncio in France, in 1947, on the eve of the United Nations decision on the creation of a Jewish state. Finally, in 1963, as Pope John XXIII, when he brought about a radical positive change in the Church's position of the Jewish people. 1) As the Apostolic Delegate in Istanbul, during the Holocaust years, Roncalli aided in various ways Jewish refugees who were in transit in Turkey, including facilitating their continued migration to Palestine. His door was always open to the representatives of Jewish Palestine, and especially to Chaim Barlas, of the Jewish Agency, who asked for his intervention in the rescue of Jews. Among his actions, one may mention his intervention with the Slovakian government to allow the exodus of Jewish children; his appeal to King Boris II of Bulgaria not to allow his country's Jews to be turned over to the Germans; his consent to transmit via the diplomatic courier to his colleague in Budapest, the Nuncio Angelo Rotta, various documents of the Jewish Agency, in order to be further forwarded to Jewish operatives in Budapest; valuable documents to aid in the protection of Jews who were authorized by the British to enter Palestine. Finally, above all -- his constant pleadings with his elders in the Vatican to aid Jews in various countries, who were in danger of deportation by the Nazis. -

„Das Gesundheitswesen Im Ghetto Theresienstadt“ 1941 – 1945

Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit „Das Gesundheitswesen im Ghetto Theresienstadt“ 1941 – 1945 Verfasser Wolfgang Schellenbacher angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. Phil.) Wien, 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt A 312 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt Geschichte Betreuerin: Univ.-Doz. Dr. Brigitte Bailer 1 Index 1. Einleitung ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Aufbau der Arbeit ........................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Quellenlage und Forschungsstand............................................................................................ 6 1.2.1 Literatur zur Ghettoselbstverwaltung............................................................................................12 2. Geschichte Theresienstadts...............................................................................................14 2.1 Planungen zur Errichtung des Ghettos Theresienstadt.....................................................14 2.2 Exkurs: Die Festung Theresienstadt ......................................................................................16 2.3 Sammel- und Durchgangslager für Juden aus dem „Protektorat“ (November 1941 bis Juni 1942)............................................................................................................................................18 2.4 Altersghetto..................................................................................................................................21 -

Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945

DECISIONS AMID CHAOS: JEWISH SURVIVAL IN BUDAPEST, MARCH 1944 – FEBRUARY 1945 Allison Somogyi A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Christopher Browning Chad Bryant Konrad Jarausch © 2014 Allison Somogyi ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Allison Somogyi: Decisions amid Chaos: Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945 (Under the direction of Chad Bryant) “The Jews of Budapest are completely apathetic and do virtually nothing to save themselves,” Raoul Wallenberg stated bluntly in a dispatch written in July 1944. This simply was not the case. In fact, Jewish survival in World War II Budapest is a story of agency. A combination of knowledge, flexibility, and leverage, facilitated by the chaotic violence that characterized Budapest under Nazi occupation, helped to create an atmosphere in which survival tactics were common and widespread. This unique opportunity for agency helps to explain why approximately 58 percent of Budapest’s 200,000 Jews survived the war while the total survival rate for Hungarian Jews was only 26 percent. Although unique, the experience of Jews within Budapest’s city limits is not atypical and suggests that, when fortuitous circumstances provided opportunities for resistance, European Jews made informed decisions and employed everyday survival tactics that often made the difference between life and death. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everybody who helped me and supported me while writing and researching this thesis. First and foremost I must acknowledge the immense support, guidance, advice, and feedback given to me by my advisor, Dr. -

Harmony of Babel Harmony of Babel Profiles of Famous Polyglots of Europe

In the late 1980s the distinguished interpreter Kató Lomb researched historical and contemporary lomb polyglots in an effort to understand their linguistic feats. Among her fellow polyglots she asked: “When can we say we know a language?” “Which is the most important language skill: grammar, vocabulary, or good pronunciation?” harmony “What method did you use to learn languages?” “Has it ever happened to you that you started learning a language, but could not cope with it?” of “What connection do you see between age and babel language learning?” “Are there ‘easy’ and ‘difficult,’ ‘rich’ and ‘poor,’ ‘beautiful’ and ‘less beautiful’ languages?” :Europe Polyglots of Famous of Profiles “What is multilingualism good for?” The answers Lomb collected from her interlocutors are singular and often profound. Grounded in real-world experience, they will be of interest to linguaphiles who are seeking to supplement their theoretical knowledge of language learning. kató lomb (1909–2003) was called “possibly HARMONY the most accomplished polyglot in the world” by linguist Stephen Krashen. One of the pioneers of simultaneous interpreting, Lomb worked in 16 languages in her native Hungary and abroad. She wrote several books on language and language of BABEL learning in the 1970s and 1980s. Profiles of Famous Polyglots of Europe http://tesl-ej.org KATÓ LOMB berkeley · kyoto HARMONY of BABEL HARMONY of BABEL profiles of famous polyglots of europe KATÓ LOMB Translated from the Hungarian by Ádám Szegi Edited by Scott Alkire tesl-ej Publications Berkeley, California & Kyoto, Japan Originally published in Hungary as Bábeli harmónia (Interjúk Európa híres soknyelvű embereivel) by Gondolat, Budapest, in 1988. -

H.U.G.E.S. a Visit to Budapest (25Th September -30Th September

H.U.G.E.S. A Visit to Budapest (25th September -30th September) 26th September, Monday The first encounter between our students and the Comenius partners took place in the hotel lobby, from where they were escorted by two volunteer students (early birds) to school. On the way to school they were given a taste of the city by the same two students, Réka Mándoki and Eszter Lévai, who introduced some of the famous buildings and let the enthusiastic teachers take several photos of them. In the morning there was a reception in school. The teachers met the head mistress, Ms Veronika Hámori, and the deputy head, Ms Katalin Szabó, who showed them around in the school building. Then, the teachers visited two classroom lessons, one of them being an English lesson where they enchanted our students with their introductory presentations describing the country they come from. The second lesson was an advanced Chemistry class, in which our guests were involved in carrying out experiments. Although they blew and blew, they didn’t blow up the school building. In the afternoon, together with the students involved in the project (8.d), we went on a sightseeing tour organised by the students themselves. A report on the event by a pupil, Viktória Bíró 8.d At the end of September my English group took a trip to the heart of Budapest. We were there with teachers from different countries in Europe. We walked along Danube Promenade, crossed Chain Bridge and went up to Fishermen’s Bastion. Fortunately, the weather was sunny and warm. -

'Owned' Vatican Guilt for the Church's Role in the Holocaust?

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 4 (2009): Madigan CP 1-18 CONFERENCE PROCEEDING Has the Papacy ‘Owned’ Vatican Guilt for the Church’s Role in the Holocaust? Kevin Madigan Harvard Divinity School Plenary presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Council of Centers on Christian-Jewish Relations November 1, 2009, Florida State University, Boca Raton, Florida Given my reflections in this presentation, it is perhaps appropriate to begin with a confession. What I have written on the subject of the papacy and the Shoah in the past was marked by a confidence and even self-righteousness that I now find embarrassing and even appalling. (Incidentally, this observation about self-righteousness would apply all the more, I am afraid, to those defenders of the wartime pope.) In any case, I will try and smother those unfortunate qualities in my presentation. Let me hasten to underline that, by and large, I do not wish to retract conclusions I have reached, which, in preparation for this presentation, have not essentially changed. But I have come to perceive much more clearly the need for humility in rendering judgment, even harsh judgment, on the Catholic actors, especially the leading Catholic actors of the period. As José Sanchez, with whose conclusions in his book on understanding the controversy surrounding the wartime pope I otherwise largely disagree, has rightly pointed out, “it is easy to second guess after the events.”1 This somewhat uninflected observation means, I take it, that, in the case of the Holy See and the Holocaust, the calculus of whether to speak or to act was reached in the cauldron of a savage world war, wrought in the matrix of competing interests and complicated by uncertainty as to whether acting or speaking would result in relief for or reprisal. -

Digital Mathematics: Bringing Google G(Math) Into the Classroom Presented By: Keirsten Pugh

Webinar Transcript: Digital Mathematics: Bringing Google g(Math) into the Classroom Presented by: Keirsten Pugh [SLIDE - WEBINAR: Digital Mathematics: Bringing Google g(Math) into the Classroom] [Image of ipad with the word g(Math) written on it Text on slide: JUNE 1st 3:30 – 4:45pm EST Presented by: Keirsten Pugh, OCT Associate Regional Coaching Manager, LEARNstyle Ltd. Image of LD@school logo Image of Twitter logo @LDatSchool #LDwebinar] [Amy Gorecki]: The LD@school team is very pleased to welcome our guest speaker Kiersten Pugh whose presentation this afternoon is entitled Digital Mathematics: Bringing Google g(Math) into the Classroom. [SLIDE – Funding for the production of this webinar was provided by the Ministry of Education] [Image of LD@school logo Text on slide: Please note that the views expressed in this webinar are the views of the presenters and do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry of Education or the Learning Disabilities Association of Ontario.] [Amy Gorecki]: The Ministry of Education provided funding for the production of this webinar. Please note that the views expressed in this webinar are the views of the presenter and do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry of Education or the Learning Disabilities Association of Ontario. [SLIDE - Don’t forget to use our social media hashtag!] [Text on slide: #LDwebinar Image of Twitter bird using megaphone @LDatSchool] [Amy Gorecki]: We will also be tweeting throughout the webinar so if you would like to participate you can send us a tweet by using our handle @LDatSchool, or the hashtag #LDwebinar. [SLIDE – WELCOME] [Images of Keirsten Pugh Text on slide: Keirsten Pugh, OCT Associate Regional Coaching Manager, LEARNstyle Ltd.] [Amy Gorecki]: That takes care of our housekeeping for this afternoon so let's get started.