The Wallenberg Affair and the Onset of the Cold War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945

DECISIONS AMID CHAOS: JEWISH SURVIVAL IN BUDAPEST, MARCH 1944 – FEBRUARY 1945 Allison Somogyi A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Christopher Browning Chad Bryant Konrad Jarausch © 2014 Allison Somogyi ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Allison Somogyi: Decisions amid Chaos: Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945 (Under the direction of Chad Bryant) “The Jews of Budapest are completely apathetic and do virtually nothing to save themselves,” Raoul Wallenberg stated bluntly in a dispatch written in July 1944. This simply was not the case. In fact, Jewish survival in World War II Budapest is a story of agency. A combination of knowledge, flexibility, and leverage, facilitated by the chaotic violence that characterized Budapest under Nazi occupation, helped to create an atmosphere in which survival tactics were common and widespread. This unique opportunity for agency helps to explain why approximately 58 percent of Budapest’s 200,000 Jews survived the war while the total survival rate for Hungarian Jews was only 26 percent. Although unique, the experience of Jews within Budapest’s city limits is not atypical and suggests that, when fortuitous circumstances provided opportunities for resistance, European Jews made informed decisions and employed everyday survival tactics that often made the difference between life and death. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everybody who helped me and supported me while writing and researching this thesis. First and foremost I must acknowledge the immense support, guidance, advice, and feedback given to me by my advisor, Dr. -

Raoul Wallenberg, Hero and Victim – His Life and Feats. by Jill Blonsky

Raoul Wallenberg, hero and victim His life and feats By Jill Blonsky About the author Jill Blonsky resides in Chester, UK. As a long-standing member of the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) she coordinates the activities of the ONG in the United Kingdom. Ms. Blonsky has a significant experience working with NGO's and charities and she holds a M.A. (Hons) degree in Russian studies with Distinction in English, Education and History subsidiaries. She also has studies in other disciplines, including Forensic Psychology and Egyptology. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) is a global-reach NGO based in New York, with offices also in Berlin, Buenos Aires and Jerusalem. The IRWF's main mission is to preserve and divulge the legacy of Raoul Wallenberg and his likes, the courageous women and men who reached-out to the victims of the Holocaust. The IRWF focuses on research and education, striving to instil the spirit of solidarity of the Rescuers in the hearts and minds of the young generations. At the same time, the IRWF organizes campaigns for Raoul Wallenberg, the victim, trying to shed light on his whereabouts. Amongst its most notable campaign, a petition to President Putin, signed by more than 20,000 people and the institution of a 500,000 Euro reward for reliable information about the fate of Raoul Wallenberg and his chauffer, Vilmos Langfelder, both of them abducted by the Soviets on January 17th, 1945. Contents: 1. The Lull before the Storm i. Attitude to Jews pre 1944 ii. The Nazis enter Hungary iii. The Allies Wake Up 2. -

The Southern Institute for Education and Research at Tulane University

The Southern Institute For Education and Research at Tulane University Presents STORIES OF HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS IN NEW ORLEANS ISAAC NEIDERMAN ISAAC NEIDERMAN WAS BORN IN TRANSYLVANIA, ROMANIA. IN 1939, NAZI-ALLIED HUNGARY ANNEXED THAT REGION. ISAAC WAS FIFTEEN YEARS OLD. JEWS WERE BEATEN, EXPROPRIATED, AND FORCED INTO GHETTOES. IN 1944, THE NAZIS AND THEIR COLLABORATORS BEGAN DEPORTING THE JEWS TO AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU DEATH CAMP IN POLAND. ISAAC WAS ORDERED INTO A NAZI “LABOR BATTALION” AND SENT TO BUDAPEST, THE HUNGARIAN CAPITAL. HE SOON ESCAPED AND OBTAINED A FALSE PASSPORT FROM RAOUL WALLENBERG, THE SWEDISH “DIPLOMAT” WHO RESCUED JEWS. ISAAC WAS LIBERATED BY RUSSIAN TROOPS IN JANUARY 1945. ISAAC COMES FROM A FAMILY OF NINE. HE IS THE ONLY SURVIVOR. THIS INTERVIEW WAS CONDUCTED BY THE SOUTHERN INSTITUTE’S PLATER ROBINSON IN 2000. PR (PLATER ROBINSON) IN (ISSAC NIEDERMAN) PR Well, Isaac, thank you very much for coming. I’d like to begin by asking you when and where you were born please. MAP OF ROMANIA ZOOMING IN ON SATU-MARE, TRANSYLVANIA IN Sure, I was born in Romania, in the state of Transylvania. The city is called Satu-Mare. It was a city of about a hundred thousand. There were twenty-five to thirty thousand Jews living in there, most of them very religious Orthodox Jews. We had a nice comfortable life there because I come from four, five generation before me, they were all Jews, they were all born there; of course it wasn’t Romania at the time, it was Hungary before the First World War. But Romania occupied it after the First World War. -

Raoul Wallenberg BASIC INFORMATION

Student presentation on Rightrous Among the Nations Raoul Wallenberg BASIC INFORMATION • Raoul Gustaf Wallenberg was born on 4th August 1912 and died probably on 17th July 1947. • He was Swedish architect, businessman, diplomat and humanitarian. • He is widely celebrated for his successful efforts to rescue between tens of thousands and one hundred thousand Jews in Nazi-occupied Hungary during the Holocaust from Hungarian Fascists and the Nazis during the later stages of World War II. BASIC INFORMATION • While serving as Sweden's special envoy in Budapest between July and December 1944, Wallenberg issued protective passports and sheltered Jews in buildings designated as Swedish territory saving tens of thousands of lives. • He was detained by Soviet authorities on suspicion of espionage and imprisoned in the prison Lubyanka in Moscow, where he reportedly died. BACKROUND • He was a member of a prominent family of bankers and industrialists. • His father died of cancer three months before he was born, and his maternal grandfather died three months after his birth. His mother and grandmother, both suddenly widows, raised him together. • After high school and eight months in the Swedish military, his paternal grandfather sent him to study in Paris, where he spent one year. In 1931, he enrolled in the University of Michigan in the United States to study architecture. • He visited Hungary on business in the early 1940s, during World War II and he became increasingly disturbed by the plans of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler to kill all the Jews of Europe. • In 1944, the World Jewish Congress and the American War Refugee Board asked Wallenberg to help and he agreed to go to Hungary to save the remaining Jews there. -

Hungary: the Assault on the Historical Memory of The

HUNGARY: THE ASSAULT ON THE HISTORICAL MEMORY OF THE HOLOCAUST Randolph L. Braham Memoria est thesaurus omnium rerum et custos (Memory is the treasury and guardian of all things) Cicero THE LAUNCHING OF THE CAMPAIGN The Communist Era As in many other countries in Nazi-dominated Europe, in Hungary, the assault on the historical integrity of the Holocaust began before the war had come to an end. While many thousands of Hungarian Jews still were lingering in concentration camps, those Jews liberated by the Red Army, including those of Budapest, soon were warned not to seek any advantages as a consequence of their suffering. This time the campaign was launched from the left. The Communists and their allies, who also had been persecuted by the Nazis, were engaged in a political struggle for the acquisition of state power. To acquire the support of those Christian masses who remained intoxicated with anti-Semitism, and with many of those in possession of stolen and/or “legally” allocated Jewish-owned property, leftist leaders were among the first to 1 use the method of “generalization” in their attack on the facticity and specificity of the Holocaust. Claiming that the events that had befallen the Jews were part and parcel of the catastrophe that had engulfed most Europeans during the Second World War, they called upon the survivors to give up any particularist claims and participate instead in the building of a new “egalitarian” society. As early as late March 1945, József Darvas, the noted populist writer and leader of the National Peasant -

Raoul Wallenberg – Not an Accidental Choice for Hungary in 1944

1 Raoul Wallenberg – Not An Accidental Choice for Hungary in 1944 Susanne Berger and Dr. Vadim Birstein On July 8, 1944, a young Swedish businessman Raoul Wallenberg, a member of an influential Swedish family of bankers and industrialists, arrived in Budapest, appointed Secretary to the Royal Swedish Legation (Embassy).2 In his work in Budapest, he also represented the American War Refugee Board (WRB), an organization established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in January 1944.3 The WRB’s task was to provide active aid to civilian victims of the Nazi and Axis powers. Although Hungary had been formally allied with Nazi Germany since 1940, on March 19, 1944 Germany had nevertheless moved to occupy the country. In a short few months, almost 500,000 Jews who had been residing in the Hungarian countryside were deported to extermination camps in Poland and Czechoslovakia. At the time of Wallenberg’s arrival in Budapest in July 1944, only 200,000 Jews living in the capital remained. Wallenberg’s initial task in Budapest was to protect a few hundred families of Jewish-Hungarian industrialists and businessmen important for the Hungarian economy. Soon his mission expanded, however. Rather than limiting the persons to be rescued to individuals with personal or business ties to Sweden, Wallenberg tried to save as many of Budapest's Jews as possible. On January 15, 1945, Raoul Wallenberg was detained by Soviet military authorities and transferred to Moscow, where he was imprisoned and investigated by Soviet military counterintelligence SMERSH.4 Presumably, Wallenberg died in Moscow's investigation prison «Lubyanka» on July 17 or shortly after – most likely, he was killed on direct orders of the Soviet leadership. -

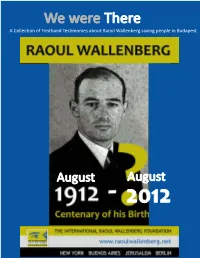

We Were There. a Collection of Firsthand Testimonies

We were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies about Raoul Wallenberg saving people in Budapest August August 2012 We Were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies About Raoul Wallenberg Saving People in Budapest 1 Contributors Editors Andrea Cukier, Daniela Bajar and Denise Carlin Proofreader Benjamin Bloch Graphic Design Helena Muller ©2012. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) Copyright disclaimer: Copyright for the individual testimonies belongs exclusively to each individual writer. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) claims no copyright to any of the individual works presented in this E-Book. Acknowledgments We would like to thank all the people who submitted their work for consideration for inclusion in this book. A special thanks to Denise Carlin and Benjamin Bloch for their hard work with proofreading, editing and fact-checking. 2 Index Introduction_____________________________________4 Testimonies Judit Brody______________________________________6 Steven Erdos____________________________________10 George Farkas___________________________________11 Erwin Forrester__________________________________12 Paula and Erno Friedman__________________________14 Ivan Z. Gabor____________________________________15 Eliezer Grinwald_________________________________18 Tomas Kertesz___________________________________19 Erwin Koranyi____________________________________20 Ladislao Ladanyi__________________________________22 Lucia Laragione__________________________________24 Julio Milko______________________________________27 -

Teacher's Guide

Teacher’s Guide Brief bios Agnes Mandl Adachi She was born in 1918, Budapest in Hungary. As a teenager, she attended Budapest's prestigious Baar Madas private school, run by the Hungarian Protestant Church. Although she was the only Jewish student there, Agnes' parents believed that the superior education at the school was important for their daughter. Agnes' father, a textile importer, encouraged his daughter to think for herself. Agnes then studied teaching techniques with famous Italian educator Maria Montessori in Italy. She was in Switzerland in 1939 to study French. She returned to Budapest in 1940. After the Germans occupied Hungary in 1944, Agnes was given refuge in the Swedish embassy. She then began to work for Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg in his efforts to save the Jews of Budapest, including the distribution of protective passes (Schutz-Pass). When the Soviets entered Budapest, Agnes decided to go to Romania. After the war, she went to Sweden and Australia before moving to the U.S. She married to Mazazumi Adachi. She published a book about Wallenberg: Adachi, Agnes, Child of the winds: my mission with Raoul Wallenberg. Chicago 1989. Ernest Bokor He was born in August 1920, in Debrad’ (Czechoslovakia, Hungarian name of the village: Debrőd; before June 1920 part of Hungary) in an observant Jewish family. In his childhood, he lived with his family in another town Dubovec (Dobóca) in Czechoslovakia. He lost his father in 1932. Ernest went to Budapest after high school to work and help his family. He was a member of the Shomer Hatzair Movement (cf.: Keywords for Teachers). -

Raoul Wallenberg: Report of the Swedish-Russian Working Group

Raoul Wallenberg Report of the Swedish-Russian Working Group STOCKHOLM 2000 Additional copies of this report can be ordered from: Fritzes kundservice 106 47 Stockholm Fax: 08-690 9191 Tel: 08-690 9190 Internet: www.fritzes.se E-mail: [email protected] Ministry for Foreign Affairs Department for Central and Eastern Europe SE-103 39 Stockholm Tel: 08-405 10 00 Fax: 08-723 11 76 _______________ Editorial group: Ingrid Palmklint, Daniel Larsson Cover design: Ingrid Palmklint Cover photo: Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest, November 1944, Raoul Wallenbergföreningen Printed by: Elanders Gotab AB, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN: ISBN: 91-7496-230-2 2 Contents Preface ..........................................7 I Introduction ...................................9 II Planning and implementation ..................12 Examining the records.............................. 16 Interviews......................................... 22 III Political background - The USSR 1944-1957 ...24 IV Soviet Security Organs 1945-1947 .............28 V Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest .................32 Background to the assignment....................... 32 Operations begin................................... 34 Protective power assignment........................ 37 Did Raoul Wallenberg visit Stockholm in late autumn 1944?.............................................. 38 VI American papers on Raoul Wallenberg - was he an undercover agent for OSS? .........40 Conclusions........................................ 44 VII Circumstances surrounding Raoul Wallenberg’s detention and arrest in Budapest -

Schult, Tanja, a Hero's Many Faces: Raoul

Page 1 of 6 Biro, Ruth. Schult, Tanja. A Hero’s Many Faces: Raoul Wallenberg in Contemporary Monuments. The Holocaust and Its Context Series. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. Pp. 425. Notes, Illustrations, Bibliography, Index. AHEA: E-journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 5 (2012): http://ahea.net/e-journal/volume-5-2012 Schult, Tanja, A Hero’s Many Faces: Raoul Wallenberg in Contemporary Monuments. The Holocaust and Its Context Series. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. Pp. 425. Notes, Illustrations, Bibliography, Index. Reviewed by Ruth G. Biro, Duquesne University This book by Swedish scholar Tanja Schult details 31 monuments in 12 countries on five continents dedicated to Raoul Wallenberg, Swedish diplomat rescuer of Jews in Budapest, Hungary in 1944-1945. The 2012 paperback edition contains some recent additions to her 2009 hardcover volume of the same title, which was a slightly revised version of her doctoral dissertation at Humboldt University, Berlin in 2007. Schult was educated in art history and Scandinavian studies in Erlangen and Lund and is currently a researcher at Stockholm University. The publisher’s series promotes international research on the Holocaust, Holocaust remembrance and interpretation, relevance of the Holocaust issues to contemporary society, and dissemination of innovative Holocaust scholarship in the English-speaking world. Schult presents an interdisciplinary socio-historical approach to Wallenberg monuments that represents the viewpoint of art history and how artists of the works expressed their ideas of Wallenberg’s deeds, fate, and legacy. She examined the dynamics of Wallenberg’s activities, the artistic interpretations of memorials to him, ways in which individuals, groups, and nations have honored Wallenberg, and how his humanitarian actions have come to symbolize moral courage against oppression, resistance to injustices, and the struggle for human rights. -

Sweden, the United States, and Raoul Wallenberg's Mission to Hungary In

MatzSweden, the United States, and Raoul Wallenberg’s Mission to Hungary in 1944 Sweden, the United States, and Raoul Wallenberg’s Mission to Hungary in 1944 ✣ Johan Matz Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/jcws/article-pdf/14/3/97/698041/jcws_a_00249.pdf by guest on 25 September 2021 Introduction Some have argued that Sweden, by commissioning Raoul Wallenberg to Bu- dapest, was the only one of the ªve neutral states in Europe to heed the U.S. request of 25 May 1944 for an increased diplomatic and consular presence in Hungary. Such a claim, however, fails to account for the particular nature of Sweden’s acceptance. The Swedish response to the request was not altogether negative, but neither was it wholly favorable. In fact, Sweden did not agree to increase the number of ofªcial government personnel at its legation in Buda- pest. What Sweden did offer was a sui generis solution with important reser- vations attached. Sweden was not alone in wanting to keep the mission at arm’s length. The United States—the initiator of the project—turned out to be even more hesitant than the Swedes about implementing it. The U.S. government was tardy in issuing instructions for the mission because the 25 May 1944 request, which was made by the United States War Refugee Board (WRB), ran coun- ter to the ofªcial policy of isolating Hungary. That the mission began at all must primarily be ascribed to the U.S. min- ister to Sweden, Herschel V. Johnson, who strove to achieve a solution accept- able to all parties. -

Holocaust Timeline

Selection from The Holocaust: A North Carolina Teacher’s Resource, North Carolina Council on the Holocaust (N.C. Dept. of Public Instruction), 2019, www.ncpublicschools.org/holocaust-council/guide/. HOLOCAUST TIME LINE North Carolina Council on the Holocaust, N.C. Dept. of Public Instruction 1932 March 13 In the presidential election in Germany, Adolf Hitler, leader of the Nazi (National Socialist) Party, receives 30% of the vote, and President Hindenburg receives 49.6%. In an April run-off election, Hitler receives 37% and Hindenburg 53%. July 31 In elections for the Reichstag (parliament), the Nazi Party receives 38%, the Social Demo- crats 22%, the Communists 14%, the Catholic Center Party 12%, and other parties 14%. 1933 Jan. 30 Hitler is appointed chancellor of Germany by President Hindenburg. Feb. 28 The Nazis use the burning of the Reichstag (parliament) building in Berlin as an excuse to suspend civil rights of all Germans in the name of national security. March 4 Franklin D. Roosevelt is inaugurated president of the United States. He remains president until his death less than one month before the end of the war in Europe. March 5 In the last free election in Germany until after World War II, the Nazis receive 44% of the popular vote in parliamentary elections. Hitler arrests the Communist parliamentary lead- ers in order to achieve a majority in the Reichstag. March 22 FIRST CONCENTRATION CAMP, Dachau, is opened in Nazi Germany to imprison poli- tical prisoners, many of them dissidents of the regime. March 24 HITLER BECOMES DICTATOR. The Reichstag gives Hitler power to enact laws without a parliamentary vote, in effect creating a dictatorship (Enabling Act).