The EJVS Mbh 1 Complete Normal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Un/Selfish Leader Changing Notions in a Tamil Nadu Village

The un/selfish leader Changing notions in a Tamil Nadu village Björn Alm The un/selfish leader Changing notions in a Tamil Nadu village Doctoral dissertation Department of Social Anthropology Stockholm University S 106 91 Stockholm Sweden © Björn Alm, 2006 Department for Religion and Culture Linköping University S 581 83 Linköping Sweden This book, or parts thereof, may be reproduced in any form without the permission of the author. ISBN 91-7155-239-1 Printed by Edita Sverige AB, Stockholm, 2006 Contents Preface iv Note on transliteration and names v Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Structure of the study 4 Not a village study 9 South Indian studies 9 Strength and weakness 11 Doing fieldwork in Tamil Nadu 13 Chapter 2 The village of Ekkaraiyur 19 The Dindigul valley 19 Ekkaraiyur and its neighbours 21 A multi-linguistic scene 25 A religious landscape 28 Aspects of caste 33 Caste territories and panchayats 35 A village caste system? 36 To be a villager 43 Chapter 3 Remodelled local relationships 48 Tanisamy’s model of local change 49 Mirasdars and the great houses 50 The tenants’ revolt 54 Why Brahmans and Kallars? 60 New forms of tenancy 67 New forms of agricultural labour 72 Land and leadership 84 Chapter 4 New modes of leadership 91 The parliamentary system 93 The panchayat system 94 Party affiliation of local leaders 95 i CONTENTS Party politics in Ekkaraiyur 96 The paradox of party politics 101 Conceptualising the state 105 The development state 108 The development block 110 Panchayats and the development block 111 Janus-faced leaders? 119 -

The Great Author of Summaries- Contemporary of Buddhaghosa

UNIVERSITY OF CEYLON REVIEW The Great Author of Summaries- Contemporary of Buddhaghosa UDDHADATTA'S Manuals of Vinaya and Abhidhamma are now known to orientalists through the editions of the Pali Text B Society. I In the Introductory Note to the Abhidhammavatiira, Mrs. C. A. F. Rhys Davids remarks: "According to the legend, Buddhadatta recast in a condensed shape that which Buddhaghosa handed on, in Pali, from the Sinhalese Commentaries. But the psychology and philosophy are pre- sented through the prism of a second vigorous intellect, under fresh aspects, in a style often less discursive and more graphic than that of the great Com- msntator, and with strikingly rich vocabulary, as is revealed by the dimensions of the Index. .. So little was the modestly expressed ambition of Buddha- datta's Commentator realized :-that the great man's death would leave others room to emerge from eclipse-a verse that forcibly recalls George Meredith's quip uttered at Tennyson's funeral-' Well, a -, it's a great day for the minor poets'!" The legend that she refers to is found in the Pali Commentary on the Vina- yavinicchaya and in the Buddhaghosu-p paiti, The former work was composed by the Sinhalese Elder, Mahasami Vacissara, in about the r zth century A.D., and is still unpublished. In its introduction it states: "Ayarn kira Bhadanta- Buddhadatt acariyo Lankadlpato sajatibhfimin Jambudipam agacchanto Bhadanta-Buddhaghosacariyau J ambudipavasikehi . mahatheravarehi kataradhanan Sihalatthakathan parivattetva . miilabhasaya tipitaka- pariyattiya atthakatham likhitum Lankadlpam gacchantam antar amagge disva sakacchaya samupaparikkhitva ... balavaparitosam patva ... 'tumhe yathadhippeta-pariyantarn likhitam atthakatham amhakam pesetha, mayam assa pan a .. -

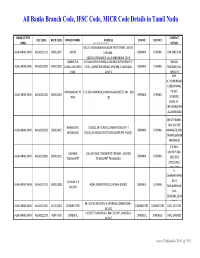

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 54.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 41] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2013 Aippasi 6, Vijaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 2893-3026 Notice .. 3026-3028 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 43888. My son, D. Ramkumar, born on 21st October 1997 43891. My son, S. Antony Thommai Anslam, born on (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 4/81C, Lakshmi 20th March 1999 (native district: Thoothukkudi), residing at Mill, West Colony, Kovilpatti, Thoothukkudi-628 502, shall Old No. 91/2, New No. 122, S.S. Manickapuram, Thoothukkudi henceforth be known as D. RAAMKUMAR. Town and Taluk, Thoothukkudi-628 001, shall henceforth be G. DHAMODARACHAMY. known as S. ANSLAM. Thoothukkudi, 7th October 2013. (Father.) M. v¯ð¡. Thoothukkudi, 7th October 2013. (Father.) 43889. I, S. Salma Banu, wife of Thiru S. Shahul Hameed, born on 13th September 1975 (native district: Mumbai), 43892. My son, G. Sanjay Somasundaram, born residing at No. 184/16, North Car Street, on 4th July 1997 (native district: Theni), residing Vickiramasingapuram, Tirunelveli-627 425, shall henceforth at No. 1/190-1, Vasu Nagar 1st Street, Bank be known as S SALMA. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2015 [Price: Rs. 31.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 9] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 4, 2015 Maasi 20, Jaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu – 2046 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages. Change of Names .. 587-664 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 8469. I, B. Sahayarani, wife of Thiru M. Bergmans, 8472. I, Janaki, wife of Thiru T. Ramesh, born on born on 3rd May 1970 (native district: Madurai), 24th April 1979 (native district: Madurai), residing at residing at No. 27, Xavier Monica Illam, K.P. Street, No. 109/32, Mela Kailasapuram, Madurai-625 018, New Ellis Nagar, Madurai-625 010, shall henceforth be shall henceforth be known as R. MURUGESWARI. known as M. SAGAYARANI. ü£ùA. B. SAHAYARANI. Madurai, 23rd February 2015. Madurai, 23rd February 2015. 8473. I, M. Ravichandran, son of Thiru K. Muthiah, 8470. I, P. Pushpa, wife of Thiru N. Jesukaran Isravel, born on 28th January 1964 (native district: Madurai), born on 16th May 1972 (native district: Kanyakumari), residing residing at Old No. 9, New No. 3/389, Kambar Salai, at No. 940/2, A-1C, S.T.C. College Road, New Zion Street, Dhinamani Nagar, Madurai-625 018, shall henceforth be Perumalpuram, Tirunelveli-627 007, shall henceforth be known as M RICHARD. -

Irrigation Infrastructure – 21 Achievements During the Last Three Years

INDEX Sl. Subject Page No. 1. About the Department 1 2. Historic Achievements 13 3. Irrigation infrastructure – 21 Achievements during the last three years 4. Tamil Nadu on the path 91 of Development – Vision 2023 of the Hon’ble Chief Minister 5. Schemes proposed to be 115 taken up in the financial year 2014 – 2015 (including ongoing schemes) 6. Inter State water Issues 175 PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT “Ú®ts« bgU»dhš ãyts« bgUF« ãyts« bgU»dhš cyf« brê¡F«” - kh©òäF jäœehL Kjyik¢r® òu£Á¤jiyé m«kh mt®fŸ INTRODUCTION: Water is the elixir of life for the existence of all living things including human kind. Water is essential for life to flourish in this world. Therefore, the Great Poet Tiruvalluvar says, “ڮϋW mikahJ cybfå‹ ah®ah®¡F« th‹Ï‹W mikahJ xG¡F” (FwŸ 20) (The world cannot exist without water and order in the world can exists only with rain) Tamil Nadu is mainly dependent upon Agriculture for it’s economic growth. Hence, timely and adequate supply of “water” is an important factor. Keeping the above in mind, I the Hon’ble Chief Minister with her vision and intention, to make Tamil Nadu a “numero uno” State in the country with “Peace, Prosperity and Progress” as the guiding principle, has been guiding the Department in the formulation and implementation of various schemes for the development and maintenance of water resources. On the advice, suggestions and with the able guidance of Hon’ble Chief Minister, the Water Resources Department is maintaining the Water Resources Structures such as, Anicuts, Tanks etc., besides rehabilitating and forming the irrigation infrastructure, which are vital for the food production and prosperity of the State. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2011 [Price: Rs. 28.00 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 31] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 17, 2011 Aadi 32, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2042 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 1789-1856 Notices .. 1857 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES My daughter, K. Revathy, born on 30th December 1995 I, Selvasundari, wife of Thiru M. Stephen Arumugam, (native district: Tirunelveli), residing at No. 41, 7th Street, born on 19th August 1961 (native district: Dindigul), residing NGO Colony, Melagaram, Tenkasi Taluk, Tirunelveli- at No. 36/34-B, New Street, Sandrorkuppam, Ambur, Vellore- 627 818, shall henceforth be known as K REVATHY DHARANI. 635 814, shall henceforth be known as M. SELVASUNDARI. SELVASUNDARI. P. KUMARVEL. Ambur, 8th August 2011. Tenkasi, 8th August 2011. (Father.) My son, I. Hariprasath, born on 8th June 1997 (native My son, Suriya, born on 22nd July 2008 (native district: district: Vellore), residing at Old No. 1/50, New No. 1/40, Tiruvallur), residing at QTR No. 1088, Block-D, Type-I Spl, Perumal Koil Street, Sethuvandai Village and Post, GC CRPF, Avadi, Chennai-600 065, shall henceforth be Katpadi Taluk, Vellore-632 602, shall henceforth be known known as P.D. -

Framework Agreement

Frame Work Agreement executed among Electronics Technology Parks Kerala (Technopark), 2015 Taurus Investment Holdings LLC and THR India Ventures LLC, for the development of the Taurus Downtown Technopark project at Technopark Phase 3, Thiruvananthapuram, India. FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT This Framework Agreement (hereinafter referred to as the "Agreement") executed at Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India on this the 30th day of September, 2015 by and amongst: Electronics Technology Parks, Kerala, Kariavattom, Thiruvananthapuram 695581, a society registered under The Travancore-Cochin Literary, Scientific and Charitable Societies (Registration) Act, 1955, with the objective of establishing information technology parks in Kerala (hereinafter referred to as 'Technopark", which expression shall unless repugnant to the meaning or context thereof, be deemed to mean and include its successors and assigns) and acting through Mr K G Girish Babu, Chief Executive Officer, consequent to full authority vested in him by its governing body for the purpose, of THE FIRST PART; AND TAURUS INVESTMENT HOLDINGS, LLC, a company incorporated under the laws of Delaware, USA and having its registered office at 22 Batterymarch Street, Boston, MA 02109, USA, hereinafter referred to as "TIH", which expression shall unless it is repugnant to the meaning or context thereof, be deemed to mean and include its successors and permitted assigns, acting through its President, Mr Erik Rijnbout, or any other Authorized Signatory by virtue of resolutions taken in the Board meeting dated -

Emerging Kerala 2012 a Global Connect Initiative

Government of Kerala Emerging Kerala 2012 A Global Connect Initiative FACT SHEET Date : 12 – 14 September 2012 Venue : Hotel Le-Meridian, Kochi, Kerala. Event Objective Objective of this Global Connect Initiative is to bring all stakeholders who are prime drivers of economy to engage in policy dialogues with the Government towards formulating a collective vision as well as to facilitate business to business linkages to enable growth. The event would also make Kerala a premier global hub of economic activity, through fostering entrepreneurship and industry, which could leverage its inherent strengths, resulting in equitable socio-economic growth. Plenary Sessions : a) Kerala Developmental Model: Enabling Faster Inclusive and Sustainable Growth b) Bridging the Infrastructure Gap: Role of PPPs to Spur Growth c) Manufacturing, International Trade and Exports d) Financial Reforms for Inclusive Growth Sectoral Conferences : Defence & Aerospace; Green Energy & Environmental Technologies; Financial Services; Food & Agro Processing; Healthcare; Education; Infrastructural Development; IT and IT Enabled Services; Manufacturing; MSMEs; Ports, Logistics and Ship Building; Science & Technology (Bio Technology, Nano Technology and Life Sciences), Tourism etc. Key Speakers / : Chief Guest: Dr Manmohan Singh, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India. Guests of Dignitaries Honour and Other Key Dignitaries: Mr Oommen Chandy, Hon’ble Chief Minister of Kerala; Mr A K Antony, Defence Minister; Mr Ghulam Nabi Azad, Minister of Health and Family Welfare; Dr Farooq Abdulla, -

Sacredkuralortam00tiruuoft Bw.Pdf

THE HERITAGE OF INDIA SERIES Planned by J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon.), D.D. (Aberdeen). Right Reverend V. S. AZARIAH, LL.D. (Cantab.), Bishop of Dornakal. E. C. BEWICK, M.A. (Cantab.) J. N. C. GANGULY. M.A. (Birmingham), {TheDarsan-Sastri. Already published The Heart of Buddhism. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., D.Litt. (Cantab.) A History of Kanarese Literature, 2nd ed. E. P. RICE, B.A. The Samkhya System, 2nd ed. A. BERRDZDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.) As"oka, 3rd ed. JAMES M. MACPHAIL, M.A., M.D. Indian Painting, 2nd ed. Principal PERCY BROWN, Calcutta. Psalms of Maratha Saints. NICOL MACNICOL, M.A. D.Litt. A History of Hindi Literature. F. E. KEAY, M.A. D.Litt. The Karma-Mlmamsa. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.) Hymns of the Tamil aivite Saints. F. KINGSBURY, B.A., and G. E. PHILLIPS, M.A. Hymns from the Rigveda. A. A. MACDONELL, M.A., Ph.D., Hon. LL.D. Gautama Buddha. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., D.Litt. (Cantab.) The Coins of India. C. J. BROWN, M.A. Poems by Indian Women. MRS. MACNICOL. Bengali Religious Lyrics, Sakta. EDWARD THOMPSON, M.A., and A. M. SPENCER, B.A. Classical Sanskrit Literature, 2nd ed. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.). The Music of India. H. A. POPLEY, B.A. Telugu Literature. P. CHENCHIAH, M.L., and RAJA M. BHUJANGA RAO BAHADUR. Rabindranath Tagore, 2nd ed. EDWARD THOMPSON, M.A. Hymns of the Alvars. J. S. M. HOOPER, M.A. (Oxon.), Madras. -

LIST of KUDIMARAMATH WORKS 2019-20 WATER BODIES RESTORATION with PARTICIPATORY APPROACH Annexure to G.O(Ms)No.58, Public Works (W2) Department, Dated 13.06.2019

GOVERNMENT OF TAMILNADU PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT WATER RESOURCES ORGANISATION ANNEXURE TO G.O(Ms.)NO. 58 PUBLIC WORKS (W2) DEPARTMENT, DATED 13.06.2019 LIST OF KUDIMARAMATH WORKS 2019-20 WATER BODIES RESTORATION WITH PARTICIPATORY APPROACH Annexure to G.O(Ms)No.58, Public Works (W2) Department, Dated 13.06.2019 Kudimaramath Scheme 2019-20 Water Bodies Restoration with Participatory Approach General Abstract Total Amount Sl.No Region No.of Works Page No (Rs. In Lakhs) 1 Chennai 277 9300.00 1 - 26 2 Trichy 543 10988.40 27 - 82 3 Madurai 681 23000.00 83 - 132 4 Coimbatore 328 6680.40 133 - 181 Total 1829 49968.80 KUDIMARAMATH SCHEME 2019-2020 CHENNAI REGION - ABSTRACT Estimate Sl. Amount No Name of District No. of Works Rs. in Lakhs 1 Thiruvallur 30 1017.00 2 Kancheepuram 38 1522.00 3 Dharmapuri 10 497.00 4 Tiruvannamalai 37 1607.00 5 Villupuram 73 2642.00 6 Cuddalore 36 815.00 7 Vellore 53 1200.00 Total 277 9300.00 1 KUDIMARAMATH SCHEME 2019-2020 CHENNAI REGION Estimate Sl. District Amount Ayacut Tank Unique No wise Name of work Constituency Rs. in Lakhs (in Ha) Code Sl.No. THIRUVALLUR DISTRICT Restoration by Removal of shoals and Reconstruction of sluice 1 1 and desilting the supply channel in Neidavoyal Periya eri Tank in 28.00 Ponneri 354.51 TNCH-02-T0210 ponneri Taluk of Thiruvallur District Restoration by Removal of shoals and Reconstruction of sluice 2 2 and desilting the supply channel in Voyalur Mamanikkal Tank in 44.00 Ponneri 386.89 TNCH-02-T0187 ponneri Taluk of Thiruvallur District Restoration by Removal of shoals and Reconstruction -

13 Maritime History of the Pearl Fishery Coast With

MARITIME HISTORY OF THE PEARL FISHERY COAST WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THOOTHUKUDI THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE MANONMANIAM SUNDARANAR UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY By Sr. S. DECKLA (Reg. No. 1090) DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY MANONMANIAM SUNDARANAR UNIVERSITY TIRUNELVELI OCTOBER 2004 13 INDEX INTRODUCTION CHAPTER ONE CHAPTER TWO CHAPTER THREE CHAPTER FOUR CHAPTER FIVE CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY 14 INTRODUCTION Different concepts have been employed by historians in different times to have a comprehensive view of the past. We are familiar with political history, social history, economic history and administrative history. Maritime history is yet another concept, which has been gaining momentum and currency these days. It (maritime history) has become a tool in the hands of several Indian historians who are interested in Indo- Portuguese history. The study of maritime history enables these researchers to come closer to the crucial dynamics of historical process. Maritime history embraces many aspects of history, such as international politics, navigation, oceanic currents, maritime transportation, coastal society, development of ports and port-towns, sea-borne trade and commerce, port-hinterland relations and so on1. As far as India and the Indian Ocean regions are concerned, maritime studies have a great relevance in the exchange of culture, establishment of political power, the dynamics of society, trade and commerce and religion of these areas. The Indian Ocean served not only as a conduit for conducting trade and commerce, but also served and still serves, as an important means of communication. The Indians have carried commodities to several Asian and African countries even before the arrival of the Europeans from India.