The Politics of Redress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concise Ancient History of Indonesia.Pdf

CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY OF INDONESIA CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY O F INDONESIA BY SATYAWATI SULEIMAN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION JAKARTA Copyright by The Archaeological Foundation ]or The National Archaeological Institute 1974 Sponsored by The Ford Foundation Printed by Djambatan — Jakarta Percetakan Endang CONTENTS Preface • • VI I. The Prehistory of Indonesia 1 Early man ; The Foodgathering Stage or Palaeolithic ; The Developed Stage of Foodgathering or Epi-Palaeo- lithic ; The Foodproducing Stage or Neolithic ; The Stage of Craftsmanship or The Early Metal Stage. II. The first contacts with Hinduism and Buddhism 10 III. The first inscriptions 14 IV. Sumatra — The rise of Srivijaya 16 V. Sanjayas and Shailendras 19 VI. Shailendras in Sumatra • •.. 23 VII. Java from 860 A.D. to the 12th century • • 27 VIII. Singhasari • • 30 IX. Majapahit 33 X. The Nusantara : The other islands 38 West Java ; Bali ; Sumatra ; Kalimantan. Bibliography 52 V PREFACE This book is intended to serve as a framework for the ancient history of Indonesia in a concise form. Published for the first time more than a decade ago as a booklet in a modest cyclostyled shape by the Cultural Department of the Indonesian Embassy in India, it has been revised several times in Jakarta in the same form to keep up to date with new discoveries and current theories. Since it seemed to have filled a need felt by foreigners as well as Indonesians to obtain an elementary knowledge of Indonesia's past, it has been thought wise to publish it now in a printed form with the aim to reach a larger public than before. -

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte KITLV, Leiden Henk Schulte Nordholt KITLV, Leiden Editorial Board Michael Laffan Princeton University Adrian Vickers Sydney University Anna Tsing University of California Santa Cruz VOLUME 293 Power and Place in Southeast Asia Edited by Gerry van Klinken (KITLV) Edward Aspinall (Australian National University) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki The Making of Middle Indonesia Middle Classes in Kupang Town, 1930s–1980s By Gerry van Klinken LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‐ Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC‐BY‐NC 3.0) License, which permits any non‐commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: PKI provincial Deputy Secretary Samuel Piry in Waingapu, about 1964 (photo courtesy Mr. Ratu Piry, Waingapu). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klinken, Geert Arend van. The Making of middle Indonesia : middle classes in Kupang town, 1930s-1980s / by Gerry van Klinken. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, ISSN 1572-1892; volume 293) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26508-0 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-26542-4 (e-book) 1. Middle class--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 2. City and town life--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 3. -

Indonesia – the Presence of the Past

lndonesia - The Presence of the Past A festschrift in honour of Ingrid Wessel Edited by Eva Streifeneder and Antje Missbach Adnan Buyung Nasution Antje Missbach Asvi Warman Adam Bernhard Dahm Bob Sugeng Hadiwinata Daniel S. Lev Doris Jedamski Eva Streifeneder Franz Magnis-Suseno SJ Frederik Holst Ingo wandelt Kees van Dijk Mary Somers Heidhues Nadja Jacubowski Robert Cribb Sri Kuhnt-Saptodewo Tilman Schiel Uta Gärtner Vedi R. Hadiz Vincent J. H. Houben Watch lndonesia! (Alex Flor, Marianne Klute, ....--.... Petra Stockmann) regioSPECTRA.___.... Indonesia — The Presence of the Past A festschrift in honour of Ingrid Wessel Edited by Eva Streifeneder and Antje Missbach Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Indonesia – The Presence of the Past. A festschrift in honour of Ingrid Wessel Eva Streifeneder and Antje Missbach (eds.) Berlin: regiospectra Verlag 2008 (2nd edition) ISBN 978-3-940-13202-4 Layout by regiospectra Cover design by Salomon Kronthaler Cover photograph by Florian Weiß Printed in Germany © regiospectra Verlag Berlin 2007 All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. For further information: http://www.regiospectra.com. Contents In Appreciation of Ingrid Wessel 9 Adnan Buyung Nasution Traces 11 Uta Gärtner Introduction 13 Antje Missbach and Eva Streifeneder Acknowledgements 17 Part I: Indonesia’s Exposure to its Past Representations of Indonesian History 21 A Critical Reassessment Vincent J. H. Houben In Search of a Complex Past 33 On the Collapse of the Parliamentary Order and the Rise of Guided Democracy in Indonesia Daniel S. -

India's Approach to Asia

INDIA’S APPROACH TO ASIA Strategy, Geopolitics and Responsibility INDIA’S APPROACH TO ASIA Strategy, Geopolitics and Responsibility Editor Namrata Goswami INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES & ANALYSES NEW DELHI PENTAGON PRESS India’s Approach to Asia: Strategy, Geopolitics and Responsibility Editor: Namrata Goswami First Published in 2016 Copyright © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi ISBN 978-81-8274-870-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining written permission of the copyright owner. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, or the Government of India. Published by PENTAGON PRESS 206, Peacock Lane, Shahpur Jat, New Delhi-110049 Phones: 011-64706243, 26491568 Telefax: 011-26490600 email: [email protected] website: www.pentagonpress.in Branch Flat No.213, Athena-2, Clover Acropolis, Viman Nagar, Pune-411014 Email: [email protected] In association with Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No. 1, Development Enclave, New Delhi-110010 Phone: +91-11-26717983 Website: www.idsa.in Printed at Avantika Printers Private Limited. Contents Foreword ix Acknowledgements xi India’s Strategic Approach to Asia 1 Namrata Goswami RISING POWERS AND THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM Rising Powers in the Emerging World Order: An Overview, with a Reflection on the Consequences for India 21 Barry Buzan ASIAN REGIONAL ORDER 1. Panchsheel–Multilateralism and Competing Regionalism: The Indian Approach towards Regional Cooperation and the Regional Order in South Asia, the Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal, and the Mekong-Ganga 35 Arndt Michael 2. -

CHAPTER 3 ‘Let Us Kill the Killer

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Voluntary participation, state involvement: Indonesian propaganda in the struggle for maintaining independence, 1945-1949 Zara, M.Y. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Zara, M. Y. (2016). Voluntary participation, state involvement: Indonesian propaganda in the struggle for maintaining independence, 1945-1949. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:05 Oct 2021 CHAPTER 3 ‘Let Us Kill the Killer. The Devilish Dutch!!’: Propaganda and Violence, 1945-1948 ¤ CHAPTER 3 ‘Let Us Kill the Killer. The Devilish Dutch!!’: Propaganda and Violence, 1945-1948 The birth of Indonesia was followed by unprecedented and extraordinary violence in the country. The Dutch-Indonesia conflict was multifaceted, consisting as it did of armed clashes between different parties—between the Indonesians and the Japanese; between the Indonesians and the British and their auxiliaries; between the Indonesians and the Dutch; and finally, among the Indonesians themselves. -

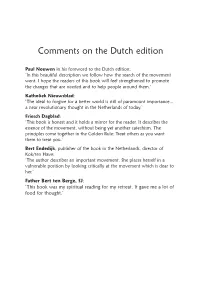

Comments on the Dutch Edition

Comments on the Dutch edition Paul Nouwen in his foreword to the Dutch edition: ‘In this beautiful description we follow how the search of the movement went. I hope the readers of this book will feel strengthened to promote the changes that are needed and to help people around them.’ Katholiek Nieuwsblad: ‘The ideal to forgive for a better world is still of paramount importance... a near revolutionary thought in the Netherlands of today.’ Friesch Dagblad: ‘This book is honest and it holds a mirror for the reader. It describes the essence of the movement, without being yet another catechism. The principles come together in the Golden Rule: Treat others as you want them to treat you.’ Bert Endedijk, publisher of the book in the Netherlands, director of Kok/ten Have: ‘The author describes an important movement. She places herself in a vulnerable position by looking critically at the movement which is dear to her.’ Father Bert ten Berge, SJ: ‘This book was my spiritual reading for my retreat. It gave me a lot of food for thought.’ Reaching for a new world Initiatives of Change seen through a Dutch window Hennie de Pous-de Jonge CAUX BOOKS First published in 2005 as Reiken naar een nieuwe wereld by Uitgeverij Kok – Kampen The Netherlands This English edition published 2009 by Caux Books Caux Books Rue de Panorama 1824 Caux Switzerland © Hennie de Pous-de Jonge 2009 ISBN 978-2-88037-520-1 Designed and typeset in 10.75pt Sabon by Blair Cummock Printed by Imprimerie Pot, 78 Av. des Communes-Réunies, 1212 Grand-Lancy, Switzerland Contents Preface -

Br 11150340000229 ZAINAL ABIDIN.Pdf

THE HISTORY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF MASHAF PUSAKA REPUBLIK INDONESIA An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted to Faculty of Ushuluddin In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Strata One (S1) Zainal Abidin 11150340000229 MAJOR OF QUR’ANIC SCIENCES AND ITS INTERPRETATION USHULUDDIN FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 1441 H/2020 M STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I hereby declare that the research entitled The History and Characteristics of Mashaf Pusaka Republik Indonesia, represents my original work and that I have used no other sources except as noted by citations. All data, tables, figures and text citations which have been reproduced from any other sources have been explicitly acknowledged as such. I have read and understood the Ministry of National Education (MoNE) of Indonesia’ Decree No.17 Year 2010 regarding plagiarism in higher education, therefore I am responsible for any claims in the future regarding the originality of my undergraduate thesis. Jakarta, Mei 19th, 2020 Zainal Abidin APPROVAL BY SUPERVISOR THE HISTORY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF MASHAF PUSAKA REPUBLIK INDONESIA An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted Faculty of Ushuluddin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Strata One (S1) Zainal Abidin NIM. 11150340000229 Approved by: Dr.Yusuf Rahman, MA NIP. 196702131992031002 MAJOR OF QUR’ANIC SCIENCES AND ITS INTERPRETATION USHULUDDIN FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 1441 H/2020 M PENGESAHAN SIDANG MUNAQASYAH Skripsi yang berjudul THE HISTORY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF MASHAF PUSAKA REPUBLIK INDONESIA telah diujikan dalam Sidang Munaqasyah Fakultas Ushuluddin, Universitas Islam Negeri (UIN) Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta pada tanggal 6 Agustus 2020. Skripsi ini telah diterima sebagai salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar Sarjana Agama (S.Ag) pada Program Studi Ilmu Al-Qur’an dan Tafsir. -

Military Justice in the Dutch East- Indies

Military Justice in the Dutch East- Indies A Study of the Theory and Practice of the Dutch Military-Legal Apparatus during the War of Indonesian Independence, 1945-1949 Utrecht University Master Thesis – RMA Modern History Steven van den Bos BA (3418707) Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Jan Hoffenaar Second Assessor: Dr. Remco Raben January 18, 2015 Contents Foreword.................................................................................................................................................3 Introduction...........................................................................................................................................4 Thesis .....................................................................................................................................................8 Structure...............................................................................................................................................10 Chapter 1: The War of Indonesian Independence...........................................................................13 Negotiations..........................................................................................................................................16 Operatie Product...................................................................................................................................18 Guerrilla Warfare..................................................................................................................................21 Operatie Kraai......................................................................................................................................23 -

The 3Rd Aprish 2018 SCHEDULE and PROGRAMS

The 3rd APRiSH 2018 SCHEDULE AND PROGRAMS Monday, August 13th 2018 Tuesday, August 14th 2018 Wednesday, August 15th 2018 ROOM 14.30 - 16.00 16.00 - 17.30 08.00 - 09.30 09.30 - 11.00 11.00 - 12.30 13.30 - 15.00 15.30 - 16.30 16.30 - 18.00 08.00 - 09.30 09.30 - 11.00 Pararellel Ses 1. Pararellel Ses 2. Pararellel Ses 3. Pararellel Ses 4. Pararellel Ses 5. Pararellel Ses 6. Pararellel Ses 7. Pararellel Ses 8. Pararellel Ses 9. Pararellel Ses 10. Rapha 1 ADM ADM ADM SKSG SKSG SKSG SKSG SKSG SKSG LAW Rapha 2 SKSG SKSG LAW LAW LAW LAW LAW LAW LAW PSY Rapha 3 LAW LAW LAW HUM HUM PSY PSY PSY PSY HUM Rapha 4 PSY HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM Rapha 5 HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM Rapha 6 HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM Rapha HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM HUM Boardroom Nissi 1 HUM HUM HUM SOC SOC HUM HUM HUM HUM ECON Nissi 2 HUM HUM SOC ECON ECON SOC SOC SOC SOC ECON Nissi 3 SOC SOC ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON Nissi 4 ECON SOC ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON Nissi 5 ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON Nissi 6 ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON Nissi ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON Boardroom Extra Room ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON ECON The 3rd APRiSH 2018 CONFERENCE PROGRAM Day 1 Monday, August 13th, 2018 Parallel Session 1 14.30-16.00 Room: Rapha 1 (ADM) Vanya Izdihar Almira & Vishnu Collaboration in the Implementation of the Government Internal Control Juwono. -

The Indonesian Red Cross Society

THE INDONESIAN RED CROSS SOCIETY History ansi Activities 1945-1977 INDONESIAN RED CROSS SOCIETY Headquarters JAKARTA THE INDONESIAN RED CROSS SOCIETY History and Activities 1945-1977 INDONESIAN RED CROSS SOCIETY Headquarters JAKARTA THE INDONESIAN RED CROSS SOCIETY HISTORY AND ACTIVITIES 1945-1977 CONTENTS s I. INTRODUCTION ...................................* 1 II. H I S T O R Y .................................. 2 III. 0 R G A N I Z A T I 0 J ...... .......•.......... 12 IV. ACTIVITIES : ' A. FIRST AID .................................... 18 ^ B. N U R S I N G ................................ 19 C. BLOODTRANS FUSION ................. -........ 21 D. DISASTER RELIEF . ............................. 24 V* DISASTER PREPAREDNESS PROGRAMM ................. 30 VI. THE ROLE IN INTERNAL CONFLICTS ................ 39 VII. THE JUNIOR RED CROSS ........................... 45 VIII. LOGISTICS ............................. 46 IX. PUBLIC RELATIONS ................................ 47 X. INTERNATIONAL RELATICMS ........................ 51 V XI. CONCLUSION ............................ 58 THE INDONESIAN RED CROSS SOCIETY HISTORY AND ACTIVITIES 1945-1977 I. INTRODUCTION The experiences of a Red Cross Society could be useful for other Societies of the same World-family, especially for new Red Cross Societies belonging to new independent States. The Indonesian Red Cross, belonging to one of the new Societies born after the Second World War, had to face many kinds of problems from the very beginning of its existence up to this moment; therefore we regard a description of its history and activities during about 30 years' of the existence as a duty to inform our public and our Sister so cieties about the objectivss., the problems, the merits and the failures as well as thf prospects of the Indonesian Red Cross Society. II. HISTORY 1 1 . H I S T O R Y -“■■■ ~ 1 On August, 17, 1945, the Indonesian people proclaims i their independence at a brief and simple ceremony in Jakarta; their spokesmen were two most prominent national leaders, SUKARNO and HATTA. -

The Corpus of Inscriptions in the Old Malay Language Arlo Griffiths

The Corpus of Inscriptions in the Old Malay Language Arlo Griffiths To cite this version: Arlo Griffiths. The Corpus of Inscriptions in the Old Malay Language. Daniel Perret. Writingfor Eternity: A Survey of Epigraphy in Southeast Asia, 30, École française d’Extrême-Orient, pp.275-283, 2018, Études thématiques. hal-01920769 HAL Id: hal-01920769 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01920769 Submitted on 13 Nov 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Writing for Eternity A Survey of Epigraphy in Southeast Asia ÉTUDES THÉMATIQUES 30 Writing for Eternity A Survey of Epigraphy in Southeast Asia Edited by: Daniel Perret 2018 Writing for Eternity: A Survey of Epigraphy in Southeast Asia Édité par / Edited by Daniel PERRET Paris, École française d’Extrême-Orient, 2018. 478 p. (Études thématiques 30) Notes en bas de page. Bibliographie. Illustrations. Résumés. Index. Footnotes. Bibliography. Illustrations. Abstracts. Index. ISSN 1269-8067 ISBN 978-2-85539-150-2 Mots clés : épigraphie ; Asie du Sud-Est ; sources ; histoire ; archéologie ; paléographie. Keywords: epigraphy; Southeast Asia; sources; history; archaeology; palaeography. Illustration de couverture : Assemblage des feuilles de l’estampage de la stèle digraphique K. -

Militias, Martial Arts and Masculinities in Timor Leste

HISTORIES OF VIOLENCE, STATES OF DENIAL – MILITIAS, MARTIAL ARTS AND MASCULINITIES IN TIMOR-LESTE Henri Myrttinen A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Conflict Resolution & Peace Studies UNIVERSITY OF KWAZULU-NATAL Supervisor: Prof. Geoff Harris Co-Supervisor: Prof. Robert Morrell 2010 DECLARATION I …Henri Myrttinen…………………………………………………declare that (i) The research reported in this dissertation/thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. (ii) This dissertation/thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. (iii) This dissertation/thesis does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. (iv) This dissertation/thesis does not contain other persons’ writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a) their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced: b) where their exact words have been used, their writing has been placed inside quotation marks, and referenced. (v) This dissertation/thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the dissertation/thesis and in the References sections. Signature: Henri Myrttinen 4 Dedicated to the memory of Sharon Kaur Jinnil (1981 – 2008) 5 Acknowledgements As solitary as writing a doctoral thesis often may seem to be, it is an impossible task without the support given in so many forms by people, organisations and institutions. The people I owe my greatest gratitude to are my parents, Riitta and Martti, who not only nurtured, encouraged and generously supported me and my siblings throughout our life but also importantly opened our lives early on to appreciate other cultures and societies.