Pintakasi: a Unifying Factor in a Local Village in the Phillipines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mother-Tongue Based Multilingual Education (MTBMLE) Initiatives in Region 8

International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE) Vol.3, No.1, March 2014, pp. 53~65 ISSN: 2252-8822 53 Mother-Tongue Based Multilingual Education (MTBMLE) Initiatives in Region 8 Voltaire Q. Oyzon1, John Mark Fullmer2 1Leyte Normal University, Tacloban City, Philippines 2Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467, United States Article Info ABSTRACT With the implementation of Mother-Tongue Based Multilingual Education Article history: (MTBMLE) under the Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013, this study set Received Dec 21, 2013 out to examine Region 8’s readiness and extant educational materials. On Revised Feb 18, 2014 the one hand, “L1 to L2 Bridge Instruction” has been shown by Hovens (2002) to engender the most substantive language acquisition, while the Accepted Feb 28, 2014 “Pure L2 immersion” approach displays the lowest results. Despite this, Region 8 (like other non-Tagalog speaking Regions) lacks primary texts in Keyword: the mother tongue, vocabulary lists, grammar lessons and, more fundamentally, the references needed for educators to create these materials. MTBMLE To fill this void, the researchers created a 377,930-word language corpus Waray language Corpus generated from 419 distinct Waray texts, which led to frequency word lists, a Waray Word List five-language classified dictionary, a 1,000-word reference dictionary with Instructional Materials pioneering part-of-speech tagging, and software for determining the grade level of Waray texts. These outputs are intended to be “best practices” Development in Waray models for other Regions. Accordingly, the researchers also created open- source, customizable software for compiling and grade-leveling texts, analyzing the grammatical nuances of each local language, and producing vocabulary lists and other materials for the Grade 1-3 classroom. -

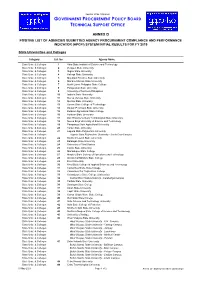

State Universities and Colleges

Republic of the Philippines GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT POLICY BOARD TECHNICAL SUPPORT OFFICE ANNEX D POSITIVE LIST OF AGENCIES SUBMITTED AGENCY PROCUREMENT COMPLIANCE AND PERFORMANCE INDICATOR (APCPI) SYSTEM INITIAL RESULTS FOR FY 2019 State Universities and Colleges Category Cat. No. Agency Name State Univ. & Colleges 1 Abra State Institute of Science and Technology State Univ. & Colleges 2 Benguet State University State Univ. & Colleges 3 Ifugao State University State Univ. & Colleges 4 Kalinga State University State Univ. & Colleges 5 Mountain Province State University State Univ. & Colleges 6 Mariano Marcos State University State Univ. & Colleges 7 North Luzon Philippine State College State Univ. & Colleges 8 Pangasinan State University State Univ. & Colleges 9 University of Northern Philippines State Univ. & Colleges 10 Isabela State University State Univ. & Colleges 11 Nueva Vizcaya State University State Univ. & Colleges 12 Quirino State University State Univ. & Colleges 13 Aurora State College of Technology State Univ. & Colleges 14 Bataan Peninsula State University State Univ. & Colleges 15 Bulacan Agricultural State College State Univ. & Colleges 16 Bulacan State University State Univ. & Colleges 17 Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University State Univ. & Colleges 18 Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology State Univ. & Colleges 19 Pampanga State Agricultural University State Univ. & Colleges 20 Tarlac State University State Univ. & Colleges 21 Laguna State Polytechnic University State Univ. & Colleges Laguna State Polytechnic University - Santa Cruz Campus State Univ. & Colleges 22 Southern Luzon State University State Univ. & Colleges 23 Batangas State University State Univ. & Colleges 24 University of Rizal System State Univ. & Colleges 25 Cavite State University State Univ. & Colleges 26 Marinduque State College State Univ. & Colleges 27 Mindoro State College of Agriculture and Technology State Univ. -

2019 Annual Report

BENGUET S T AT E U NIVERSI T Y 2019 ANNUAL REPORT ACADEMIC SECTOR 2019 ANNUAL REPORT: ACADEMIC SECTOR 2019 Table of Contents I. CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION .......................................................................................................... 3 A. Degree Programs and Short Courses ........................................................................................ 3 B. Program Accreditation .............................................................................................................. 6 C. Program Certification ................................................................................................................ 9 II. STUDENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 10 A. Enrolment ................................................................................................................................ 10 B. Student Awards ....................................................................................................................... 17 C. Student Scholarship and RA 10931 Implementation .............................................................. 19 D. Student Development ............................................................................................................. 20 E. Student Mobility ...................................................................................................................... 21 F. Graduates ............................................................................................................................... -

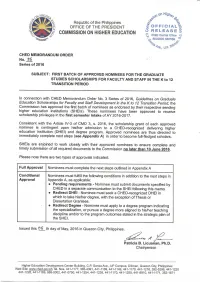

CMO No. 26, Series of 2016

List of Approved SHEI Nominees for Graduate Scholarships in the K to 12 Transition Program BATCH 1 SENDING HIGHER REGION EDUCATION NAME OF FACULTY / PROGRAM TITLE APPLIED FOR PROGRAM DELIVERING HEI (IF REMARKS INSTITUTION (SHEI) STAFF STATUS KNOWN/PROSPECTIVE) 1 ASIACAREER Reyno, Miriam Joy M. Master in Business Administration New Master's Lyceum-Northwestern Redirect Degree, COLLEGE University Redirect DHEI FOUNDATION, INC. 1 COLEGIO DE Baquiran, Brylene Ann Doctor of Philosophy major in New Doctorate Not Stated DAGUPAN R. Educational Management Bautista, Chester Allan Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Redirect Degree F. Caralos, Edilberto Jr. L. Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated Columbino, Marvin B. MS Electronics Engineering New Master's Saint Louis University Dela Cruz, Anna Clarissa Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated R. Dela Cruz, Vivian A. Doctor of Philosophy Ongoing Not Stated Doctorate Fernandez, Hajibar Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated Jhoneil L. Fortin, Arnaldy D. Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Gabriel, Jr. Renato J. Master in Communication major New Master's De La Salle University, Taft in Applied Medical Studies Page 1 of 183 Lachica, Evangeline N. Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Landingin, Mark Joseph Master of Arts in Philosophy New Master's Not Stated D. Macaranas, Jin Benir C. Master of Science in Electrical New Master's Saint Louis University Engineering Navarro, Adessa Bianca Master in Business Administration Ongoing Not Stated G. Master's Ordonez, Jesse Jr. P. Doctor of Philosophy New Doctorate Not Stated Seco, Cristian Rey C. -

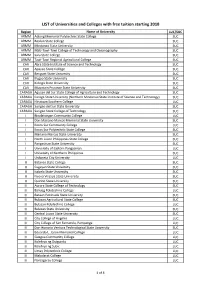

LIST of Universities and Colleges with Free Tuition Starting 2018

LIST of Universities and Colleges with free tuition starting 2018 Region Name of University LUC/SUC ARMM Adiong Memorial Polytechnic State College SUC ARMM Basilan State College SUC ARMM Mindanao State University SUC ARMM MSU-Tawi-Tawi College of Technology and Oceanography SUC ARMM Sulu State College SUC ARMM Tawi-Tawi Regional Agricultural College SUC CAR Abra State Institute of Science and Technology SUC CAR Apayao State College SUC CAR Benguet State University SUC CAR Ifugao State University SUC CAR Kalinga State University SUC CAR Mountain Province State University SUC CARAGA Agusan del Sur State College of Agriculture and Technology SUC CARAGA Caraga State University (Northern Mindanao State Institute of Science and Technology) SUC CARAGA Hinatuan Southern College LUC CARAGA Surigao del Sur State University SUC CARAGA Surigao State College of Technology SUC I Binalatongan Community College LUC I Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University SUC I Ilocos Sur Community College LUC I Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College SUC I Mariano Marcos State University SUC I North Luzon Philippines State College SUC I Pangasinan State University SUC I University of Eastern Pangasinan LUC I University of Northern Philippines SUC I Urdaneta City University LUC II Batanes State College SUC II Cagayan State University SUC II Isabela State University SUC II Nueva Vizcaya State University SUC II Quirino State University SUC III Aurora State College of Technology SUC III Baliuag Polytechnic College LUC III Bataan Peninsula State University SUC III Bulacan Agricultural State College SUC III Bulacan Polytechnic College LUC III Bulacan State University SUC III Central Luzon State University SUC III City College of Angeles LUC III City College of San Fernando, Pampanga LUC III Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University SUC III Eduardo L. -

Stress: Its Causes, Effects, and the Coping Mechanisms Among Bachelor of Science in Social Work Students in a Philippine University

International Journal for Innovation Education and Research www.ijier.net Vol:-3 No-8, 2015 Stress: Its Causes, Effects, And The Coping Mechanisms Among Bachelor Of Science In Social Work Students In A Philippine University Generoso N. Mazo, Ph.D. Associate Professor 1 Leyte Normal University Tacloban City Philippines 6500 [email protected] Abstract The causes, levels of stress, and coping mechanisms vary. The study of Social Work course is basically a rigorous one as it is designed to prepare students for the actual demands in the world of work, specifically on social issues and problems and on community organizing. This study sought to determine the causes of stress, the effects of stress, and the stress coping mechanisms of Bachelor of Science in Social Work students in the Leyte Normal University, Tacloban City. It tested some assumptions using the descriptive survey method with 54 respondents. Quizzes/examinations, school requirements/projects and recitations were the most common stressors. Sleepless nights was the common effects of stress. There was disparity on the causes and effects of stress between the male and female respondents. Praying to God was the common stress coping mechanism. No disparity was observed between the male and female coping mechanisms. Keywords: Stress, Causes of stress, Effects of Stress, Coping mechanism. Introduction Stress affects people from all walks of life regardless of age, gender, civil status, political affiliation, religious belief, economic status and profession. It affects decision-makers such as the politician, the manager, the priest or pastor, the employee, the housewife, the student, the out-of-school-youths, the driver, and even the jobless. -

Annual Report 2019

BENGUET STATE UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2019 VISION MISSION Republic of the Philippines Benguet State University A PREMIER UNIVERSITY To provide quality education delivering world-class to enhance food security, 2601 La Trinidad, Benguet education that promotes sustainable communities, www.bsu.edu.ph sustainable development industry innovation, climate amidst climate change resilience, gender equality, Office of the Unive rsity President institutional development and partnerships HIS EXCELLENCY RODRIGO ROA DUTERTE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES President Goal I. To develop proactive programs to ensure relevant quality education Republic of the Philippines Objectives: Malacañan Palace, Manila 1.To benchmark curricular and co-curricular programs with national and international standards 2.To develop alternative learning experiences to enhance skills that match industry needs 3.To develop innovative and relevant curricular and co-curricular programs 4.To enhance proactive student welfare and development programs Dear Mr. President, Goal II. To develop proactive programs for quality service Objectives: 1.To enhance relevant human resource development programs This is to submit the Benguet State University 2019 Annual Report. 2.To develop effective and efficient innovative platforms for cascading information 3.To enhance and develop employee welfare programs Goal III. To enhance responsive systems and procedures for transparent institutional development The report highlights significant achievements of the University in the various offices, Objectives: colleges and institutes under the sectors of Academic Affairs, Research and Extension, 1.To enhance and develop innovative financial management systems 2.To ensure transparency in all transactions in the university Administration and Finance, Business Affairs and offices under the President. 3.To ensure inclusive and consultative decision making Goal IV. -

Download This PDF File

International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE) Vol.5, No.4, December2016, pp. 292~299 ISSN: 2252-8822 292 Preference of Students on the Format of Options in a Multiple-Choice Test Voltaire Q. Oyzon1, Hermabeth O. Bendulo2, Erlinda D. Tibus3, Rhodora A. Bande4, Myrna L. Macalinao5 1,5 Leyte Normal University, Philippines 2,3 Southern Leyte State University-Tomas Oppus, Philippines 4 Visayas State University, Philippines Article Info ABSTRACT Article history: Schools in the Philippines, especially those that are offering teacher education programs, are advised to construct examinations that are Licensure Received Sep 18, 2016 Examination for Teachers (LET)-like test items. This is because “if any Revised Nov 27, 2016 aspect of a test is unfamiliar to candidates, they are likely to perform less Accepted Nov 30, 2016 well than they would do otherwise on subsequently taking a parallel version, for example.” Using the education students of Leyte Normal University, Southern Leyte State University-Tomas Oppus Campus, and Visayas State Keywords: University, this study determined the students’ preference on the arrangements/format of options in a multiple-choice test through a survey Language testing questionnaire. Moreover, it tried to find out the reasons behind the Letter case options preferences. Mean, frequency and Chi-square tests were used in the analysis Multiple-choice test of data. Results revealed that the cascading arrangement is the most preferred Preference arrangement of options and the one-line horizontal arrangement is the least Psychology of choice preferred arrangement of options in a multiple-choice test. The reasons identified were organized and easy to read, less confusing and easier to distinguish and vertically arranged thus require less eye movement. -

No. School Campus / Address No. School Campus / Address No

ANNEX B * STATE UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES No. School Campus / Address No. School Campus / Address No. School Campus / Address Polytechnic University of the 1 Bataan Peninsula State University All Campuses 20 Eastern Visayas State University All Campuses 39 All Campuses Philippines Ramon Magsaysay Technological 2 Batangas State University All Campuses 21 Ifugao State University All Campuses 40 All Campuses University 3 Benguet State University All Campuses 22 Isabela State University All Campuses 41 Rizal Technological University All Campuses 4 Bicol University All Campuses 23 Kalinga-Apayao State College All Campuses 42 Samar State University All Campuses 5 Bukidnon State University All Campuses 24 Leyte Normal University All Campuses 43 Sultan Kudarat State University All Campuses 6 Bulacan State University All Campuses 25 Mariano Marcos State University All Campuses 44 Tarlac College of Agriculture All Campuses Mindanao University of Science and 7 Cagayan State University All Campuses 26 All Campuses 45 Tarlac State University All Campuses Technology Mt. Province State Polytechnic Technological University of the 8 Camarines Sur Polytechnic College All Campuses 27 All Campuses 46 All Campuses College Philippines 9 Capiz State University All Campuses 28 Naval State University All Campuses 47 University of Antique All Campuses 10 Catanduanes State College All Campuses 29 Negros Oriental State University All Campuses 48 University of Eastern Philippines All Campuses 11 Cavite State University All Campuses 30 Northwest Samar State University -

The Rotary Foundation-Active Donors All Time Giving: US$125,462.00 Major Donor – Paul Harris Society (1): Mark O

17 TH REGULAR MEETING March 11, 2021 RC Tacloban Clubhouse, Tacloban City ProgrammePROGRAMME Call to Order Pres. Eugene Tan Invocation Sec. Jocal Calvara Pambansang Awit Audio Visual Presentation Recitation of Object of Rotary & 4-Way Test Rtn. Benjie Retuerto Rotary Hymn Audio Visual Presentation Introduction of Guests & Visiting Rotarians Dir. Richard De Jesus Welcome Song Dir. Richard De Jesus Joke Time Rtn. Roy Nebrija Recognition Time IPP Bonet Tordillo Introduction of Guest Speaker Sec. Jocal Calvara Message Justice Bautista “Butch” Gler Corpin, Jr. Court of Appeals Magistrate President’s Time Pres. Eugene Tan Night Chairman Dir. Richard De Jesus Host Team TEAM VACCINE facebook: Rotary Club of Tacloban Email: [email protected] 1 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE... Greetings my brothers in the Rotary Club of Tacloban. We gather on this, our 17th Regular meeting, on a somber atmosphere. We have received news that PP Bon Mutia has joined our Creator. Last February 1, we also lost one of our Past President, PP Antonio Cam. We share the grief and sympathies with the family and give our prayers for their eternal repose and comfort to those they survived. This brings us to a closer perspective of our lives as Rotarians. We are limited by the time we spend here on earth. In spite of the said limit, we strive to make our lives as meaningful and purposeful as possible. We strive to make our own mark and leave a legacy to those who we are leaving. PP Bon and PP Tony made their own mark. Serving as active members and presidents of our club, they have passed on the younger generations of Rotarians the legacy of a leader leaving a club for us to be in fellowship with. -

The Waray Culture Is a Response to a Need and a Challenge

1 PREFACE This writing on the Waray culture is a response to a need and a challenge. The dearth of a systematic body of knowledge to understand a people who are the fourth largest ethnolinguistic group in the Philippines and who occupy the third largest island in the archipelago pressed the author to respond to that need. The unconsolidated data from various sources here and there and the absence of venues for discourse pose a formidable challenge for any writer. The changing landscapes and seascapes in the island worlds of Samar and Leyte islands are compelling. The cultural worker is bound to get to work – retrieve and document and advocate for the conservation of the natural and cultural wealth there are. But these cannot be frozen in a time warp. Time moves on and life goes on. Generations past are gone and generations now will produce and raise the next ones. How do we bring them to the world of the next millennium? We are limited by our own lifeline. As the Jesuit chronicler Father Francisco Alcina did in the 1600s, the necessary act is to write. Write or things would be forgotten. Write or else nobody would know of how people in this part the world made meaning of their lives. Write or else nobody would know of us at all. Write so our children would know and understand themselves. Write of what is, has been and could be so they would see the paths that they could take, not just to survive but to live happily. This monograph on the Waray is an ordering of the seeming helter-skelter information, written and oral, recollections and reflections, memories and current meanderings of thoughts on the savoring of Waray food as the pristinely fresh kinilaw or of a moment of ringing laughter over a friend’s funny anecdote over a sip of tuba. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Tuning in to Survive: Media and Disaster Mitigation in Post-Yolanda Philippines Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3bm2c0z5 Author Guyton, Shelley Publication Date 2021 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Tuning in to Survive: Media and Disaster Mitigation in Post-Yolanda Philippines A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Shelley Tuazon Guyton March 2021 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christina Schwenkel, Chairperson Dr. Sally Ness Dr. Derick Fay Copyright by Shelley Tuazon Guyton 2021 The Dissertation of Shelley Tuazon Guyton is approved: __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside This dissertation is dedicated to the survivors and victims of Typhoon Yolanda. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I reflect with gratitude toward the many, many interested individuals and organizations who have helped this research move through every step. Although I am unable to acknowledge everyone by name here, I hope you, the reader, can feel as you read the text that the perspectives and hundreds of people fulfilled this research. First and foremost, I am grateful to the Taclobanons willing to share their experiences and perspectives with a foreign student. I have been humbled by your bravery in reliving painful moments, and in communicating to me and your local authorities that something must be done. I cannot thank you by name because I choose to keep my participants’ identities masked to ensure their protection.