Mother-Tongue Based Multilingual Education (MTBMLE) Initiatives in Region 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Science Teaching to Bicolano Students: in Bicol, English Or Filipino?

International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE) Vol.4, No.1, March2015, pp. 8~15 ISSN: 2252-8822 8 Primary Science Teaching to Bicolano Students: In Bicol, English or Filipino? Jualim Datiles Vela Division of Educational Development, Cultural and Regional Studies Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University, Japan Article Info ABSTRACT Article history: This study aimed to determine the effects of using the local and mother languages on primary students’ academic performance in science, which is Received Nov 30, 2014 officially taught in English. Usingthe official language, English, and the two Revised Dec 30, 2014 local languages- Filipino, the national and official language, and Bicol, the Accepted Jan 26, 2015 mother language of the respondents- science lessons were developed and administered to three randomly grouped students. After each science lesson, the researcher administered tests in three languages to the three groups of Keyword: students to determine their comprehension of science lessons in the three languages. The findings indicated that students who were taught using the Primary science education Filipino language obtained better mean scores in the test compared to Mother Tongue-based Science students who were taught using their mother language. On the other hand, Education students who were taught using the English language obtained the lowest Instructional Materials in Local mean scores. Furthermore, the results revealed that the Bicol speaking Languages students prefer the Filipino language during class discussions, recitations, in following their teacher’s instructions during science related classroom activities, and in doing their homework. Copyright © 2015 Institute of Advanced Engineering and Science. -

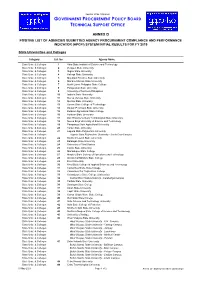

State Universities and Colleges

Republic of the Philippines GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT POLICY BOARD TECHNICAL SUPPORT OFFICE ANNEX D POSITIVE LIST OF AGENCIES SUBMITTED AGENCY PROCUREMENT COMPLIANCE AND PERFORMANCE INDICATOR (APCPI) SYSTEM INITIAL RESULTS FOR FY 2019 State Universities and Colleges Category Cat. No. Agency Name State Univ. & Colleges 1 Abra State Institute of Science and Technology State Univ. & Colleges 2 Benguet State University State Univ. & Colleges 3 Ifugao State University State Univ. & Colleges 4 Kalinga State University State Univ. & Colleges 5 Mountain Province State University State Univ. & Colleges 6 Mariano Marcos State University State Univ. & Colleges 7 North Luzon Philippine State College State Univ. & Colleges 8 Pangasinan State University State Univ. & Colleges 9 University of Northern Philippines State Univ. & Colleges 10 Isabela State University State Univ. & Colleges 11 Nueva Vizcaya State University State Univ. & Colleges 12 Quirino State University State Univ. & Colleges 13 Aurora State College of Technology State Univ. & Colleges 14 Bataan Peninsula State University State Univ. & Colleges 15 Bulacan Agricultural State College State Univ. & Colleges 16 Bulacan State University State Univ. & Colleges 17 Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University State Univ. & Colleges 18 Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology State Univ. & Colleges 19 Pampanga State Agricultural University State Univ. & Colleges 20 Tarlac State University State Univ. & Colleges 21 Laguna State Polytechnic University State Univ. & Colleges Laguna State Polytechnic University - Santa Cruz Campus State Univ. & Colleges 22 Southern Luzon State University State Univ. & Colleges 23 Batangas State University State Univ. & Colleges 24 University of Rizal System State Univ. & Colleges 25 Cavite State University State Univ. & Colleges 26 Marinduque State College State Univ. & Colleges 27 Mindoro State College of Agriculture and Technology State Univ. -

Waray Language Medium of Instruction in Primary Grade Mathematics

IOSR Journal of Mathematics (IOSR-JM) e-ISSN: 2278-5728, p-ISSN: 2319-765X. Volume 14, Issue 4 Ver. III (Jul - Aug 2018), PP 56-62 www.iosrjournals.org Waray Language Medium of Instruction in Primary Grade Mathematics JOY B. ARAZA Corresponding Author: JOY B. ARAZA Abstract: This qualitative study utilized descriptive phenomenological approach. It aimed to investigate the lived experiences of the primary grade teachers teaching grade 1 to grade 3 in mathematics subject using waray (mother tongue) language as a medium of instructions. Participants are primary grade teachers teaching mathematics in Catbalogan 2 districts, for the school year 2017 - 2018; semi-structured, face-to-face interviews and observation were the instruments used in the data gathering.From the data analyses, three major themed emerged: (1)it is easier to teach mathematics using waray (mother tongue) language ; (2) Waraylanguage of instruction make the lessons or discussion more interactive and students centered(3) Challenges encountered by the primary grade teachers in mathematics using waray language. In the challenges encountered by the teachers threesub themes was emerged that is; Difficulty in teaching numbers and shapes, In adequacy of instructional materials and evaluation test is not written in waray language. This study concluded that waray language can be used in teaching mathematics. Keywords: Waraylanguage, medium of instruction, mother tongue, mathematics ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 02-08-2018 Date of acceptance: 18-08-2018 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------ I. Introduction: Language is the key to communication. It can provide bridges to new opportunities, or build barriers to equality. It connects, and disconnects. It creates unity, and can cause conflict. -

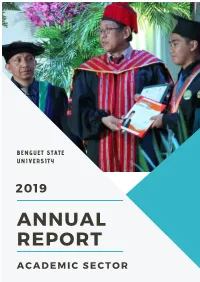

2019 Annual Report

BENGUET S T AT E U NIVERSI T Y 2019 ANNUAL REPORT ACADEMIC SECTOR 2019 ANNUAL REPORT: ACADEMIC SECTOR 2019 Table of Contents I. CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION .......................................................................................................... 3 A. Degree Programs and Short Courses ........................................................................................ 3 B. Program Accreditation .............................................................................................................. 6 C. Program Certification ................................................................................................................ 9 II. STUDENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 10 A. Enrolment ................................................................................................................................ 10 B. Student Awards ....................................................................................................................... 17 C. Student Scholarship and RA 10931 Implementation .............................................................. 19 D. Student Development ............................................................................................................. 20 E. Student Mobility ...................................................................................................................... 21 F. Graduates ............................................................................................................................... -

Literacy Instruction in the Mother Tongue: the Case of Pupils Using Mixed Vocabularies Alma Sonia Q

Journal of International Education Research – Third Quarter 2013 Volume 9, Number 3 Literacy Instruction In The Mother Tongue: The Case Of Pupils Using Mixed Vocabularies Alma Sonia Q. Sanchez, Leyte Normal University, Philippines ABSTRACT In the institutionalization of the mother tongue-based multilingual education (MTB-MLE) in the country, several trainings were conducted introducing its unique features such as the use of the two-track method in teaching reading based on the frequency of the sounds of the first language (L1). This study attempted to find out how the accuracy track method worked with Waray pupils using mixed vocabularies. This is a part of a developmental study that aims to improve Waray reading instruction in basic education. The researcher used a checklist of the 100 Most Common Words in Waray for pretest and posttest, interviews, survey questionnaires, and daily observations during the three-week implementation of the method. The averages of the pretest and posttest scores were compared. Themes and patterns in the responses were likewise analyzed. The results showed a big gap in the performance of pupils classified as readers and beginning readers. Several issues and challenges met were also identified. These imply that the method is less facilitative for effective teaching and learning in Waray of speakers using mixed vocabularies. This study recommends to modify the method or to develop an appropriate method for literacy instruction of speakers without a strong linguistic foundation in their mother tongue. Keywords: Mother Tongue Literacy Instruction; Multilingual Education; Mixed Vocabularies INTRODUCTION he use of mother tongue provides children with an equitable opportunity to access and facilitate learning. -

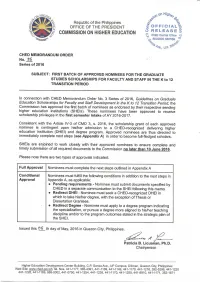

CMO No. 26, Series of 2016

List of Approved SHEI Nominees for Graduate Scholarships in the K to 12 Transition Program BATCH 1 SENDING HIGHER REGION EDUCATION NAME OF FACULTY / PROGRAM TITLE APPLIED FOR PROGRAM DELIVERING HEI (IF REMARKS INSTITUTION (SHEI) STAFF STATUS KNOWN/PROSPECTIVE) 1 ASIACAREER Reyno, Miriam Joy M. Master in Business Administration New Master's Lyceum-Northwestern Redirect Degree, COLLEGE University Redirect DHEI FOUNDATION, INC. 1 COLEGIO DE Baquiran, Brylene Ann Doctor of Philosophy major in New Doctorate Not Stated DAGUPAN R. Educational Management Bautista, Chester Allan Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Redirect Degree F. Caralos, Edilberto Jr. L. Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated Columbino, Marvin B. MS Electronics Engineering New Master's Saint Louis University Dela Cruz, Anna Clarissa Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated R. Dela Cruz, Vivian A. Doctor of Philosophy Ongoing Not Stated Doctorate Fernandez, Hajibar Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated Jhoneil L. Fortin, Arnaldy D. Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Gabriel, Jr. Renato J. Master in Communication major New Master's De La Salle University, Taft in Applied Medical Studies Page 1 of 183 Lachica, Evangeline N. Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Landingin, Mark Joseph Master of Arts in Philosophy New Master's Not Stated D. Macaranas, Jin Benir C. Master of Science in Electrical New Master's Saint Louis University Engineering Navarro, Adessa Bianca Master in Business Administration Ongoing Not Stated G. Master's Ordonez, Jesse Jr. P. Doctor of Philosophy New Doctorate Not Stated Seco, Cristian Rey C. -

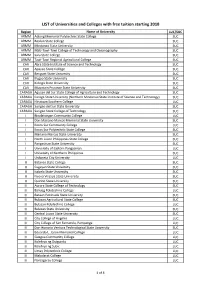

LIST of Universities and Colleges with Free Tuition Starting 2018

LIST of Universities and Colleges with free tuition starting 2018 Region Name of University LUC/SUC ARMM Adiong Memorial Polytechnic State College SUC ARMM Basilan State College SUC ARMM Mindanao State University SUC ARMM MSU-Tawi-Tawi College of Technology and Oceanography SUC ARMM Sulu State College SUC ARMM Tawi-Tawi Regional Agricultural College SUC CAR Abra State Institute of Science and Technology SUC CAR Apayao State College SUC CAR Benguet State University SUC CAR Ifugao State University SUC CAR Kalinga State University SUC CAR Mountain Province State University SUC CARAGA Agusan del Sur State College of Agriculture and Technology SUC CARAGA Caraga State University (Northern Mindanao State Institute of Science and Technology) SUC CARAGA Hinatuan Southern College LUC CARAGA Surigao del Sur State University SUC CARAGA Surigao State College of Technology SUC I Binalatongan Community College LUC I Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University SUC I Ilocos Sur Community College LUC I Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College SUC I Mariano Marcos State University SUC I North Luzon Philippines State College SUC I Pangasinan State University SUC I University of Eastern Pangasinan LUC I University of Northern Philippines SUC I Urdaneta City University LUC II Batanes State College SUC II Cagayan State University SUC II Isabela State University SUC II Nueva Vizcaya State University SUC II Quirino State University SUC III Aurora State College of Technology SUC III Baliuag Polytechnic College LUC III Bataan Peninsula State University SUC III Bulacan Agricultural State College SUC III Bulacan Polytechnic College LUC III Bulacan State University SUC III Central Luzon State University SUC III City College of Angeles LUC III City College of San Fernando, Pampanga LUC III Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University SUC III Eduardo L. -

The Oral Aurality of the Radio Waray Siday 118

Tenasas / The Oral Aurality of the Radio Waray Siday 118 THE ORAL AURALITY OF THE RADIO WARAY SIDAY Maria Rocini E. Tenasas Ateneo de Manila University Leyte Normal University [email protected] Abstract The end of print culture raises many disturbing questions about the position of poetry amidst these immense cultural and technological changes. What will be the place of the poet and his poetry in society now that we are at the cutting edge of technology? What will be the advantage of poetry in what Walter J. Ong calls the technologizing of the word? This study focuses on how the Waray siday as vernacular poetry from the margins emerges into a new form of oral history, known now as secondary orality, as it finds its way on the radio. It analyzes the distinct oral and aural qualities of the radio Waray siday as oral poetry, and how this soundscape somehow contributed to the characteristics of Waray language as reflected in the radio Waray siday. It illustrates how the interplay of orality and aurality create sense and affect in the radio Waray siday that makes it a revitalized, modernized, and powerful poetry. Analysis is grounded on the affect theory which posits that the affective power of the voice (orality), combined with the intimacy of the listening process (aurality), results in a change in behavior realized by listening to the reading of oral poetry; the orality theory which contends the intrinsic superiority of oral to written poetry, even in the age of print; and the radio inclusive theory which shows the link between the radio text, context, and reception. -

9.5.2 Final Report of Samar Island Size

DOCUMENTATION OF PHILIPPINE TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICES IN HEALTH: THE PEOPLE OF SAMAR ISLAND NATURAL PARK, SAMAR ISLAND A collaborative project of Communities in Samar Island Natural Park, Samar Island: Guirang, Balagon, San Isidro, San Vicente, Hiduroma, Pinamorotan, Burak, and Bagacay Local governments of Basey, Canavid, Las Navas, Dolores, San Jose de Buan, Calbayog, Llorente, and Hinabangan Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care – Department of Health Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau – Department of Environment and Natural Resources Samar Island Natural Park Office University of the Philippines Tacloban University of Eastern Philippines University of the Philippines Manila – National Institutes of Health (Institute of Herbal Medicine), College of Medicine, and School of Health Sciences, Palo, Leyte 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. REMINDER Page i II. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Page ii III. ABSTRACT Page 1 IV. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY Page 3 V. METHODOLOGY Page 5 VI. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION A. BASEY WATERSHED Page 11 BARANGAY GUIRANG, BASEY, SAMAR The study area Gathering information and herbarium vouchers The informants Tables of ethnopharmacological uses of natural materials B. CANAVID WATERSHED Page 29 BARANGAY BALAGON, CANAVID, EASTERN SAMAR The study area Gathering information and herbarium vouchers The informants Tables of ethnopharmacological uses of natural materials C. CATUBIG WATERSHED Page 51 BARANGAY SAN ISIDRO, LAS NAVAS, NORTHERN SAMAR The study area Gathering information and herbarium vouchers The informants Tables of ethnopharmacological uses of natural materials D. DOLORES WATERSHED Page 123 BARANGAY SAN VICENTE, DOLORES, EASTERN SAMAR The study area Gathering information and herbarium vouchers The informants Tables of ethnopharmacological uses of natural materials E. GANDARA WATERSHED Page 173 BARANGAY HIDUROMA, SAN JOSE DE BUAN, SAMAR The study area Gathering information and herbarium vouchers The informants Tables of ethnopharmacological uses of natural materials F. -

Stress: Its Causes, Effects, and the Coping Mechanisms Among Bachelor of Science in Social Work Students in a Philippine University

International Journal for Innovation Education and Research www.ijier.net Vol:-3 No-8, 2015 Stress: Its Causes, Effects, And The Coping Mechanisms Among Bachelor Of Science In Social Work Students In A Philippine University Generoso N. Mazo, Ph.D. Associate Professor 1 Leyte Normal University Tacloban City Philippines 6500 [email protected] Abstract The causes, levels of stress, and coping mechanisms vary. The study of Social Work course is basically a rigorous one as it is designed to prepare students for the actual demands in the world of work, specifically on social issues and problems and on community organizing. This study sought to determine the causes of stress, the effects of stress, and the stress coping mechanisms of Bachelor of Science in Social Work students in the Leyte Normal University, Tacloban City. It tested some assumptions using the descriptive survey method with 54 respondents. Quizzes/examinations, school requirements/projects and recitations were the most common stressors. Sleepless nights was the common effects of stress. There was disparity on the causes and effects of stress between the male and female respondents. Praying to God was the common stress coping mechanism. No disparity was observed between the male and female coping mechanisms. Keywords: Stress, Causes of stress, Effects of Stress, Coping mechanism. Introduction Stress affects people from all walks of life regardless of age, gender, civil status, political affiliation, religious belief, economic status and profession. It affects decision-makers such as the politician, the manager, the priest or pastor, the employee, the housewife, the student, the out-of-school-youths, the driver, and even the jobless. -

ISO 639-3 Code Change Request 2009-083

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code Change Request Number: 2009-083 (completed by Registration authority) Date: 2009-8-25 Primary Person submitting request: Jason Lobel Affiliation: University of Hawai'i at Manoa E-mail address: jasonlobel1 at yahoo dot com Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: William Hall, SIL Philippines, william_hall at sil dot org Postal address for primary contact person for this request (in general, email correspondence will be used): PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set and will be posted on the ISO 639-3 website. Types of change requests This form is to be used in requesting changes (whether creation, modification, or deletion) to elements of the ISO 639 Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages. The types of changes that are possible are to 1) modify the reference information for an existing code element, 2) propose a new macrolanguage or modify a macrolanguage group; 3) retire a code element from use, including merging its scope of denotation into that of another code element, 4) split an existing code element into two or more new language code elements, or 5) create a new code element for a previously unidentified language variety. Fill out section 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 below as appropriate, and the final section documenting the sources of your information. The process by which a change is received, reviewed and adopted is summarized on the final page of this form. -

Annual Report 2019

BENGUET STATE UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2019 VISION MISSION Republic of the Philippines Benguet State University A PREMIER UNIVERSITY To provide quality education delivering world-class to enhance food security, 2601 La Trinidad, Benguet education that promotes sustainable communities, www.bsu.edu.ph sustainable development industry innovation, climate amidst climate change resilience, gender equality, Office of the Unive rsity President institutional development and partnerships HIS EXCELLENCY RODRIGO ROA DUTERTE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES President Goal I. To develop proactive programs to ensure relevant quality education Republic of the Philippines Objectives: Malacañan Palace, Manila 1.To benchmark curricular and co-curricular programs with national and international standards 2.To develop alternative learning experiences to enhance skills that match industry needs 3.To develop innovative and relevant curricular and co-curricular programs 4.To enhance proactive student welfare and development programs Dear Mr. President, Goal II. To develop proactive programs for quality service Objectives: 1.To enhance relevant human resource development programs This is to submit the Benguet State University 2019 Annual Report. 2.To develop effective and efficient innovative platforms for cascading information 3.To enhance and develop employee welfare programs Goal III. To enhance responsive systems and procedures for transparent institutional development The report highlights significant achievements of the University in the various offices, Objectives: colleges and institutes under the sectors of Academic Affairs, Research and Extension, 1.To enhance and develop innovative financial management systems 2.To ensure transparency in all transactions in the university Administration and Finance, Business Affairs and offices under the President. 3.To ensure inclusive and consultative decision making Goal IV.