UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Disasters in the Philippines: a Case Study of the Immediate Causes and Root Drivers From

Zhzh ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 Environment & Natural Resources Program Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/ENRP The authors of this report invites use of this information for educational purposes, requiring only that the reproduced material clearly cite the full source: Franta, Benjamin, et al, “Climate disasters in the Philippines: A case study of immediate causes and root drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, November 2016. Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: A destroyed church in Samar, Philippines, in the months following Typhoon Yolanda/ Haiyan. (Benjamin Franta) Copyright 2016, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 The Environment and Natural Resources Program (ENRP) The Environment and Natural Resources Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs is at the center of the Harvard Kennedy School’s research and outreach on public policy that affects global environment quality and natural resource management. -

Saksi December 16 2020 Pinoy TV Channel

Saksi December 16, 2020 | Pinoy TV Channel Saksi December 16, 2020 | Pinoy TV Channel 1 / 2 Share the best GIFs now >>> Kapamilya Teleserye GIFs Jun 12, 2020 · MANILA—Already ... HD Pinoy Teleserye Jun 17, 2021 · Watch ABS CBN Kapamilya Channel Teleserye It's ... List of programs broadcast by Kapamilya Channel Mar 16, 2021 · Ang Sayo Ay Akin Kapamilya Teleserye. ... Pinoy Tv. Saksi March 17 2021 .. Dec 15, 2020 — Watch Online Pinoy TV Drama Love in Sadness December 16, 2020, TodayFull Episode in Hd. Pinoy Channel Love in Sadness December 16, ... May 14, 2021 — Pinoy Tambayan: Pinoy Tv Jul 02, 2021 · 24 Oras July 1 2021 Today . ... PINOY TV May 14, 2021 · Pinoy TV Replay | Pinoy TV Channel | Pinoy Tambayan ... Teleserye Dec 16, 2020 · Watch Pinoy TV, Pinoy Lambingan, Pinoy .... Jun 11, 2021 - Pinoy Tambayan - Watch 24 Oras June 12 2021 Replay. ... Pinoy Tv Has a Lot of Pinoy Tambayan List That on Air in The Philipines Tv Shows.. Jun 18, 2020 — news channels, with only 10% using email news in Finland. • The proportion ... Notable changes over the last 12 months include a 16-percentage point fall in ... GMA Network (24 Oras, Saksi, GMA News TV). ABS-CBN (TV .... Bible-based videos for families, teenagers, and children. Documentaries about Jehovah's Witnesses. Watch or download. This is the official DEclips channel of GMA Pinoy TV, the flagship international ... Meteor Garden September 17 2020 in By Pinoy TV September 16, 2020.. Pinoy Channel has a Lot of TV Drama Like Go Back Couple December 16 2020 Online. Stay tuned with us .... OFWteleserye.su - Watch your favorite Pinoy TV Channel, Pinoy Tambayan, Pinoy Teleserye Replay, Pinoy TV Series and Pinoy TV Shows online for free! Download the official mobile app of GMA Network and get instant access to the latest news and entertainment updates delivered by the most awarded and most ... -

(RECEIVING HALL) PE Madrid Book

Title Author Year published Publisher QuantityPhysical Description Remarks Language Category Best of the best - Philippines n.a 2014 Eastgate Publishing Corp. 1 Hardbound English Tourism Bucket List - Philippines n.a n.d Eastgate Publishing Co. 5 Hardbound English Tourism Libros y Bibliotecas: Tesoros del Ministerio de Defensa n.a n.d Ministerio de Defensa 1 Hardbound Spanish References Peace through interfaith dialogue n.a 2010 Department of Foreign Affairs 1 Hardbound English International Relations Nurturing Philippines-Brunei Ties: Economic and Cultural Diplomacy Program of the Embassy ofn.a the Philippines in Brunei2018 DarussalamEmbassy 2015-2017 of the Philippines - Brunei Darussalam 1 Hardbound English International Relations Bayang Magiliw: Finding Bel Paese (Philippine-Italian Relations) Lhuillier, Philippe J. 2009 Great Minds Media, Incorporated 1 Hardbound English International Relations Sikap: Sipag at Abilidad ng mga Pilipino n.a 2017 Department of Trade and Industry 1 Hardbound English Coffee table Books Then and Now n.a 2019 ookien Times Philippines Yearbook Publishing Co.1 Paperback English Coffee table Books Being Truly Filipino: Personal Expressions of An Identity Conchitina Sevilla-Bernardo 2006 karilagan E-Professionals, Inc 1 Hardbound English Arts & Culture Salvador F. Bernal: Designing The Stage Nicanor G. Tiongson 2007 National Commission for Culture & Arts 2 Hardbound English Arts & Culture Crossing Parallels Isabel M. Echevarria 2017 Lodestar Press Inc. 1 Hardbound English Arts & Culture Casas Sevillanas: desde la Edad Media hasta el Barroco Teodoro Falcon Marquez 2012 Editorial Maratania 1 Hardbound Spanish Arts & Culture Filipiniana Juan Guardiola 2006 n.a 1 Hardbound Spanish & English Arts & Culture Philippine Style Design & Architecture Lucia Tettoni & Eizabeth V. -

Bridges Across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia

Bridges across Oceans Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia April 2010 0 2010 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. Published 2010. Printed in the Philippines ISBN 978-971-561-896-0 Publication Stock No. RPT101731 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Bridges across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2010. 1. Transport Infrastructure. 2. Southeast Asia. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ADB encourages printing or copying information exclusively for personal and noncommercial use with proper acknowledgment of ADB. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works for commercial purposes without the express, written consent of ADB. Note: In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 -

Mother-Tongue Based Multilingual Education (MTBMLE) Initiatives in Region 8

International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE) Vol.3, No.1, March 2014, pp. 53~65 ISSN: 2252-8822 53 Mother-Tongue Based Multilingual Education (MTBMLE) Initiatives in Region 8 Voltaire Q. Oyzon1, John Mark Fullmer2 1Leyte Normal University, Tacloban City, Philippines 2Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467, United States Article Info ABSTRACT With the implementation of Mother-Tongue Based Multilingual Education Article history: (MTBMLE) under the Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013, this study set Received Dec 21, 2013 out to examine Region 8’s readiness and extant educational materials. On Revised Feb 18, 2014 the one hand, “L1 to L2 Bridge Instruction” has been shown by Hovens (2002) to engender the most substantive language acquisition, while the Accepted Feb 28, 2014 “Pure L2 immersion” approach displays the lowest results. Despite this, Region 8 (like other non-Tagalog speaking Regions) lacks primary texts in Keyword: the mother tongue, vocabulary lists, grammar lessons and, more fundamentally, the references needed for educators to create these materials. MTBMLE To fill this void, the researchers created a 377,930-word language corpus Waray language Corpus generated from 419 distinct Waray texts, which led to frequency word lists, a Waray Word List five-language classified dictionary, a 1,000-word reference dictionary with Instructional Materials pioneering part-of-speech tagging, and software for determining the grade level of Waray texts. These outputs are intended to be “best practices” Development in Waray models for other Regions. Accordingly, the researchers also created open- source, customizable software for compiling and grade-leveling texts, analyzing the grammatical nuances of each local language, and producing vocabulary lists and other materials for the Grade 1-3 classroom. -

The Impact of Tropical Cyclone Hayan in the Philippines: Contribution of Spatial Planning to Enhance Adaptation in the City of Tacloban

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS Faculdade de Ciências Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Faculdade de Letras Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia Instituto de Ciências Sociais Instituto Superior de Agronomia Instituto Superior Técnico The impact of tropical cyclone Hayan in the Philippines: Contribution of spatial planning to enhance adaptation in the city of Tacloban Doutoramento em Alterações Climáticas e Políticas de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Especialidade em Ciências do Ambiente Carlos Tito Santos Tese orientada por: Professor Doutor Filipe Duarte Santos Professor Doutor João Ferrão Documento especialmente elaborado para a obtenção do grau de Doutor 2018 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS Faculdade de Ciências Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Faculdade de Letras Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia Instituto de Ciências Sociais Instituto Superior de Agronomia Instituto Superior Técnico The impact of tropical cyclone Haiyan in the Philippines: Contribution of spatial planning to enhance adaptation in the city of Tacloban Doutoramento em Alterações Climáticas e Políticas de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Especialidade em Ciências do Ambiente Carlos Tito Santos Júri: Presidente: Doutor Rui Manuel dos Santos Malhó; Professor Catedrático Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa Vogais: Doutor Carlos Daniel Borges Coelho; Professor Auxiliar Departamento de Engenharia Civil da Universidade de Aveiro Doutor Vítor Manuel Marques Campos; Investigador Auxiliar Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil(LNEC) -

State Universities and Colleges

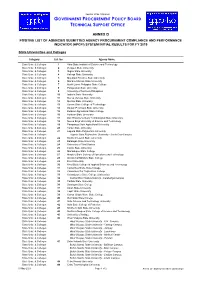

Republic of the Philippines GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT POLICY BOARD TECHNICAL SUPPORT OFFICE ANNEX D POSITIVE LIST OF AGENCIES SUBMITTED AGENCY PROCUREMENT COMPLIANCE AND PERFORMANCE INDICATOR (APCPI) SYSTEM INITIAL RESULTS FOR FY 2019 State Universities and Colleges Category Cat. No. Agency Name State Univ. & Colleges 1 Abra State Institute of Science and Technology State Univ. & Colleges 2 Benguet State University State Univ. & Colleges 3 Ifugao State University State Univ. & Colleges 4 Kalinga State University State Univ. & Colleges 5 Mountain Province State University State Univ. & Colleges 6 Mariano Marcos State University State Univ. & Colleges 7 North Luzon Philippine State College State Univ. & Colleges 8 Pangasinan State University State Univ. & Colleges 9 University of Northern Philippines State Univ. & Colleges 10 Isabela State University State Univ. & Colleges 11 Nueva Vizcaya State University State Univ. & Colleges 12 Quirino State University State Univ. & Colleges 13 Aurora State College of Technology State Univ. & Colleges 14 Bataan Peninsula State University State Univ. & Colleges 15 Bulacan Agricultural State College State Univ. & Colleges 16 Bulacan State University State Univ. & Colleges 17 Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University State Univ. & Colleges 18 Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology State Univ. & Colleges 19 Pampanga State Agricultural University State Univ. & Colleges 20 Tarlac State University State Univ. & Colleges 21 Laguna State Polytechnic University State Univ. & Colleges Laguna State Polytechnic University - Santa Cruz Campus State Univ. & Colleges 22 Southern Luzon State University State Univ. & Colleges 23 Batangas State University State Univ. & Colleges 24 University of Rizal System State Univ. & Colleges 25 Cavite State University State Univ. & Colleges 26 Marinduque State College State Univ. & Colleges 27 Mindoro State College of Agriculture and Technology State Univ. -

Diaspora Philanthropy: the Philippine Experience

Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience ______________________________________________________________________ Victoria P. Garchitorena President The Ayala Foundation, Inc. May 2007 _________________________________________ Prepared for The Philanthropic Initiative, Inc. and The Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University Supported by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ____________________________________________ Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience I . The Philippine Diaspora Major Waves of Migration The Philippines is a country with a long and vibrant history of emigration. In 2006 the country celebrated the centennial of the first surge of Filipinos to the United States in the very early 20th Century. Since then, there have been three somewhat distinct waves of migration. The first wave began when sugar workers from the Ilocos Region in Northern Philippines went to work for the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association in 1906 and continued through 1929. Even today, an overwhelming majority of the Filipinos in Hawaii are from the Ilocos Region. After a union strike in 1924, many Filipinos were banned in Hawaii and migrant labor shifted to the U.S. mainland (Vera Cruz 1994). Thousands of Filipino farm workers sailed to California and other states. Between 1906 and 1930 there were 120,000 Filipinos working in the United States. The Filipinos were at a great advantage because, as residents of an American colony, they were regarded as U.S. nationals. However, with the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, which officially proclaimed Philippine independence from U.S. rule, all Filipinos in the United States were reclassified as aliens. The Great Depression of 1929 slowed Filipino migration to the United States, and Filipinos sought jobs in other parts of the world. -

Anjeski, Paul OH133

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with PAUL ANJESKI Human Resources/Psychologist, Navy, Vietnam War Era 2000 OH 133 1 OH 133 Anjeski, Paul, (1951- ). Oral History Interview, 2000. User Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 84 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Master Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 84 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Video Recording: 1 videorecording (ca. 84 min.); ½ inch, color. Transcript: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Abstract: Paul Anjeski, a Detroit, Michigan native, discusses his Vietnam War era experiences in the Navy, which include being stationed in the Philippines during social unrest and the eruption of Mount Pinatubo. Anjeski mentions entering ROTC, getting commissioned in the Navy in 1974, and attending Damage Control Officer School. He discusses assignment to the USS Hull as a surface warfare officer and acting as navigator. Anjeski explains how the Hull was a testing platform for new eight-inch guns that rattled the entire ship. After three and a half years aboard ship, he recalls human resources management school in Millington (Tennessee) and his assignment to a naval base in Rota (Spain). Anjeski describes duty as a human resources officer and his marriage to a female naval officer. He comments on transferring to the Naval Reserve so he could attend graduate school and his work as part of a Personnel Mobilization Team. He speaks of returning to duty in the Medical Service Corps and interning as a psychologist at Bethesda Hospital (Maryland), where his duties included evaluating people for submarine service, trauma training, and disaster assistance. -

Download Download

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 21, Number 5, May 2020 E-ISSN: 2085-4722 Pages: 1823-1832 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d210508 Morphological variation of two common sea grapes (Caulerpa lentillifera and Caulerpa racemosa) from selected regions in the Philippines JEREMAIAH L. ESTRADA♥, NONNATUS S. BAUTISTA, MARIBEL L. DIONISIO-SESE Plant Biology Division, Institute of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Los Baños. College, Laguna 4031, Philippines. ♥email: [email protected] Manuscript received: 26 February 2020. Revision accepted: 6 April 2020. Abstract. Estrada JL, Bautista NS, Dionisio-Sese ML. 2020. Morphological variation of two common sea grapes (Caulerpa lentillifera and Caulerpa racemosa) from selected regions in the Philippines. Biodiversitas 21: 1823-1832. Seagrapes, locally known in the Philippines as “lato” or “ar-arusip”, are economically important macroalgae belonging to the edible species of the genus Caulerpa. This study characterized and compared distinct populations of sea grapes from selected regions in the Philippines and described the influence of physicochemical parameters of seawater on their morphology. Morphometric, cluster and principal component analyses showed that morphological plasticity exists in sea grapes species (Caulerpa lentillifera and Caulerpa racemosa) found in different sites in the Philippines. These are evident in morphometric parameters namely, assimilator height, space between assimilators, ramulus diameter and number of rhizoids on stolon wherein significant differences were found. This evident morphological plasticity was analyzed in relation to physicochemical parameters of the seawater. Assimilator height of C. racemosa is significantly associated and highly influenced by water depth, salinity, temperature and dissolved oxygen whereas for C. lentillifera depth and salinity are the significant influencing factors. -

Camotes Island, Have You Heard There You Can Find Respite Where Time Slows Down As You Enjoy the Rustic Charms of Island Life

In a cave, I bathed in a lagoon With waters cool even at noon Off a cliff, I jumped today And landed in paradise, I’d say In quiet white sand beaches there On to the sunset I sat and stared Leaving the rush of city life behind Finding peace in heart and mind Camotes Island, have you heard There you can find respite Where time slows down as you enjoy The rustic charms of island life A castaway’s reverie Camotes Island Camotes Island, Cebu © Isla Snapshots thickening mangrove roots feeding fish feeding roots: Nature gives and takes. Perfect spot for tranquility Bakhaw beach is ideal for travelers who © Gonzalo Ang wish to have a taste of the island’s beach without having to worry for distractions since waves and breeze are the only prominent sound present in this place. Couple’s bliss One of the main attractions on the island, Danao © Isla Snapshots Imagination is the only limit Buho rock is also famous for its © Gonzalo Ang A child’s heart Buho Rock is a cliff-diving spot from different © Allan Geraldez Lake, is also known as Lover’s Lake. True to its name, it offers landmark ship-shaped coral rock that looks like it is docked to a cliff heights. Unleashing the child in oneself, an adrenaline junkie may cliff breath-taking scenery and a romantic panorama. at Poblacion port dive and feel a good space of nothing but fresh air before touching the clear waters of Camotes sea. 26 PwC Philippines VisMin’s Philippine Gems 27 Tulang Diot Camotes Island, Cebu, Visayas Camotes N Geography and people Timubo Cave Camotes Islands is a group of Lake Danao islands located in the Camotes Sea of the Philippines. -

Philippine Studies Ateneo De Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines The Philippine Press System: 1811-1989 Doreen G. Fernandez Philippine Studies vol. 37, no. 3 (1989) 317–344 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Fri June 27 13:30:20 2008 Philippine Studies 37 (1989): 317-44 The Philippine Press System: 1811-1989 DOREEN G. FERNANDEZ The Philippine press system evolved through a history of Spanish colonization, revolution, American colonization, the Commonwealth, independence, postwar economy and politics, Martial Law and the Marcos dictatorship, and finally the Aquino government. Predictably, such a checkered history produced a system of tensions and dwel- opments that is not easy to define. An American scholar has said: When one speaks of the Philippine press, he speaks of an institution which began in the seventeenth century but really did not take root until the nineteenth century; which overthrew the shackles of three governments but became enslaved by its own members; which won a high degree of freedom of the press but for years neglected to accept the responsibilities inherent in such freedom.