Marco Ferreri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habemus Papam

Fandango Portobello presents a Sacher Films, Fandango and le Pacte production in collaboration with Rai and France 3 Cinema HABEMUS PAPAM a film by Nanni Moretti Running Time: 104 minutes International Fandango Portobello sales: London office +44 20 7605 1396 [email protected] !"!1!"! ! SHORT SYNOPSIS The newly elected Pope suffers a panic attack just as he is due to appear on St Peter’s balcony to greet the faithful, who have been patiently awaiting the conclave’s decision. His advisors, unable to convince him he is the right man for the job, seek help from a renowned psychoanalyst (and atheist). But his fear of the responsibility suddenly thrust upon him is one that he must face on his own. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !"!2!"! CAST THE POPE MICHEL PICCOLI SPOKESPERSON JERZY STUHR CARDINAL GREGORI RENATO SCARPA CARDINAL BOLLATI FRANCO GRAZIOSI CARDINAL PESCARDONA CAMILLO MILLI CARDINAL CEVASCO ROBERTO NOBILE CARDINAL BRUMMER ULRICH VON DOBSCHÜTZ SWISS GUARD GIANLUCA GOBBI MALE PSYCHOTHERAPIST NANNI MORETTI FEMALE PSYCHOTHERAPIST MARGHERITA BUY CHILDREN CAMILLA RIDOLFI LEONARDO DELLA BIANCA THEATER COMPANY DARIO CANTARELLI MANUELA MANDRACCHIA ROSSANA MORTARA TECO CELIO ROBERTO DE FRANCESCO CHIARA CAUSA MASTER OF CEREMONIES MARIO SANTELLA CHIEF OF POLICE TONY LAUDADIO JOURNALIST ENRICO IANNIELLO A MOTHER CECILIA DAZZI SHOP ASSISTANT LUCIA MASCINO TV JOURNALIST MAURIZIO MANNONI HALL PORTER GIOVANNI LUDENO GIRL AT THE BAR GIULIA GIORDANO BARTENDER FRANCESCO BRANDI BOY AT THE BUS LEONARDO MADDALENA PRIEST SALVATORE MISCIO DOCTOR SALVATORE -

The Machine at the Mad Monster Party

1 The Machine at the Mad Monster Party Mad Monster Party (dir. Jules Bass, 1967) is a beguiling film: the superb Rankin/Bass “Animagic” stop-motion animation is burdened by interminable pacing, the celebrity voice cast includes the terrific Boris Karloff and Phyllis Diller caricaturing themselves but with flat and contradictory dialogue, and its celebration of classic Universal Studios movie monsters surprisingly culminates in their total annihilation in the film’s closing moments. The plot finds famous Dr. Baron Boris von Frankenstein convening his “Worldwide Organization of Monsters” to announce both his greatest discovery, a “formula which can completely destroy all matter,” and his retirement, where he will surprisingly be succeeded not by a monster but by something far worse: a human, his nebbish pharmacist nephew Felix Flanken. Naturally, this does not sit well with the current membership, nor even Felix, who is exposed to monsters for the first time in his life and is petrified at what he sees. Thus, a series of classic monsters team up to try to knock off Felix and take over for Baron Frankenstein: Dracula, The Werewolf, The Mummy, The Invisible Man, Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde, The Creature from the Black Lagoon, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Frankenstein’s Monster, The Monster's Mate, King Kong (referred to only as “It”), Yetch (an ersatz Peter Lorre/Igor hybrid), and Francesca, the buxom red-head secretary. Much of the plot’s comedy is that Felix is so humanly clueless: glasses-wearing, naive, constantly sneezing, he fails to recognize the monsters’ horribleness and manages to avoid their traps mainly by accident and dumb luck. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

MA RCD FERUIP1, F'f Gt'a" PÌ-120 CA, Ccir(I) 1);?-10.(Ja)E{,0 T)E- I

Ferrario, Davide 624 625 Ferreri, Marco ce off rivelando la sua verginità. Deve in- Bibliografia: Davide Ferrario, in Sopralluoghi e Doni- gnala uno dal terrompere gli studi per fare il servizio civi- meritai-i, Torino Film Festival, 1998; Lorenzo Pelliz, Processo di Kafka, cui pensa già nel cita della regolarizzazione dei rapporti: già le, buona occasione per lasciare la famiglia. zar!, Davide Ferrario, Frammenti aguzzi di un discorso 1959, e che costituisce una sugge- El pisito rivela l'intrigante legame fra pro- amoroso, in '>Cineforum»,2000, n. 391. stione di fondo presente in L'udienza. Pur con qualche concessione allo stile da vi- prietà e relazione coniugale, in La donna Quella di Marco Ferreri è una figura atipi- deoclip, il film funziona grazie all'ottimo scimmia questa diventa addirittura il crisma ca nel panorama del cinema italiano, per gli montaggio, all'inventiva della regia e all'in- che permette il cinico sfruttamento della Ferreri, Marco umori che nutrono i suoi film, per le in- terprete, Valerio Mastandrea, talento comi- donna. La storia di L'ape regina - (Milano, 1928 - Parigi, 1997). Studi regola-. un mari- fluenze, per lo stile fatto di accostamenti to progressivamente s'avvia alla morte per co naturale. Fiume di parole, musica e im- ri a Milano, s'iscrive, senza raggiungere la stranianti e di commistioni insolite. Già i adempiere all'«obbligo coniugale» - mette magini, Tutti giú per terra diverte senza vol- laurea, alla facoltà di Veterinaria. L'inte- primi tre film, girati in Spagna (un contesto in luce il dirottamento dell'istinto sessuale garità né cali di ritmo. -

Toho Co., Ltd. Agenda

License Sales Sheet October 2018 TOHO CO., LTD. AGENDA 1. About GODZILLA 2. Key Factors 3. Plan & Schedule 4. Merchandising Portfolio Appendix: TOHO at Glance 1. About GODZILLA About GODZILLA | What is GODZILLA? “Godzilla” began as a Jurassic creature evolving from sea reptile to terrestrial beast, awakened by mankind’s thermonuclear tests in the inaugural film. Over time, the franchise itself has evolved, as Godzilla and other creatures appearing in Godzilla films have become a metaphor for social commentary in the real world. The characters are no longer mere entertainment icons but embody emotions and social problems of the times. 2018 © TOHO CO., LTD. All rights reserved/ Confidential & Proprietary 4 About GODZILLA | Filmography Reigning the Kaiju realm for over half a century and prevailing strong --- With its inception in 1954, the GODZILLA movie franchise has brought more than 30 live-action feature films to the world and continues to inspire filmmakers and creators alike. Ishiro Honda’s “GODZILLA”81954), a classic monster movie that is widely regarded as a masterpiece in film, launched a character franchise that expanded over 50 years with 29 titles in total. Warner Bros. and Legendary in 2014 had reintroduced the GODZILLA character to global audience. It contributed to add millennials to GODZILLA fan base as well as regained attention from generations who were familiar with original series. In 2017, the character has made a transition into new media- animated feature. TOHO is producing an animated trilogy to be streamed in over 190 countries on NETFLIX. 2018 © TOHO CO., LTD. All rights reserved/ Confidential & Proprietary 5 Our 360° Business Film Store TV VR/AR Cable Promotion Bluray G DVD Product Exhibition Publishing Event Music 2018 © TOHO CO., LTD. -

Hiol 20 11 Fraser.Pdf (340.4Kb Application/Pdf)

u 11 Urban Difference “on the Move”: Disabling Mobil- ity in the Spanish Film El cochecito (Marco Ferreri, 1960) Benjamin Fraser Introduction Pulling from both disability studies and mobility studies specifically, this ar- ticle offers an interdisciplinary analysis of a cult classic of Spanish cinema. Marco Ferreri’s filmEl cochecito (1960)—based on a novel by Rafael Azcona and still very much an underappreciated film in scholarly circles—depicts the travels of a group of motorized-wheelchair owners throughout urban (and rural) Madrid. From a disability studies perspective, the film’s focus on Don Anselmo, an able-bodied but elderly protagonist who wishes to travel as his paraplegic friend, Don Lucas, does, suggests some familiar tropes that can be explored in light of work by disability theorists.1 From an (urbanized) mobil- ity studies approach, the characters’ movements through the Spanish capital suggest the familiar image of a filmic Madrid of the late dictatorship, a city that was very much culturally and physically “on the move.”2 Though not un- problematic in its nuanced portrayal of the relationships between able-bodied and disabled Madrilenians, El cochecito nonetheless broaches some implicit questions regarding who has a right to the city and also how that right may be exercised (Fraser, “Disability Art”; Lefebvre; Sulmasy). The significance of Ferreri’s film ultimately turns on its ability to “universalize” disability and connect it to the contemporary urban experience in Spain. What makes El cochecito such a complex film—and such a compelling one—is how a nuanced view of (dis)ability is woven together with explicit narratives of urban modernity and implicit narratives of national progress. -

Uw Cinematheque Announces Fall 2012 Screening Calendar

CINEMATHEQUE PRESS RELEASE -- FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AUGUST 16, 2012 UW CINEMATHEQUE ANNOUNCES FALL 2012 SCREENING CALENDAR PACKED LINEUP INCLUDES ANTI-WESTERNS, ITALIAN CLASSICS, PRESTON STURGES SCREENPLAYS, FILMS DIRECTED BY ALEXSEI GUERMAN, KENJI MISUMI, & CHARLES CHAPLIN AND MORE Hot on the heels of our enormously popular summer offerings, the UW Cinematheque is back with the most jam-packed season of screenings ever offered for the fall. Director and cinephile Peter Bogdanovich (who almost made an early version of Lonesome Dove during the era of the revisionist Western) writes that “There are no ‘old’ movies—only movies you have already seen and ones you haven't.” With all that in mind, our Fall 2012 selections presented at 4070 Vilas Hall, the Chazen Museum of Art, and the Marquee Theater at Union South offer a moveable feast of outstanding international movies from the silent era to the present, some you may have seen and some you probably haven’t. Retrospective series include five classic “Anti-Westerns” from the late 1960s and early 70s; the complete features of Russian master Aleksei Guerman; action epics and contemplative dramas from Japanese filmmaker Kenji Misumi; a breathtaking survey of Italian Masterworks from the neorealist era to the early 1970s; Depression Era comedies and dramas with scripts by the renowned Preston Sturges; and three silent comedy classics directed by and starring Charles Chaplin. Other Special Presentations include a screening of Yasujiro Ozu’s Dragnet Girl with live piano accompaniment and an in-person visit from veteran film and television director Tim Hunter, who will present one of his favorite films, Tsui Hark’s Shanghai Blues and a screening of his own acclaimed youth film, River’s Edge. -

Company Profile Fenix Entertainment About Us

COMPANY PROFILE FENIX ENTERTAINMENT ABOUT US Fenix Entertainment is a production company active also in the music industry, listed on the stock exchange since August 2020, best newcomer in Italy in the AIM-PRO segment of the AIM ITALIA price list managed by Borsa Italiana Spa. Its original, personalized and cutting-edge approach are its defining features. The company was founded towards the end of 2016 by entrepreneurs Riccardo di Pasquale, a former bank and asset manager and Matteo Di Pasquale formerly specializing in HR management and organization in collaboration with prominent film and television actress Roberta Giarrusso. A COMBINATION OF MANY SKILLS AT THE SERVICE OF ONE PASSION. MILESTONE 3 Listed on the stock exchange since 14 Produces the soundtrack of Ferzan Produces the film ‘’Burraco Fatale‘’. August 2020, best newcomer in Italy in Ozpetek's “Napoli Velata” the AIM-PRO segment of the AIM ITALIA price list managed by Borsa Italiana Spa First co-productions Produces the soundtrack "A Fenix Entertainment cinematographic mano disarmata" by Claudio Distribution is born Bonivento Acquisitions of the former Produces the television Produces the film works in the library series 'That’s Amore' “Ostaggi” Costitution Fenix Attend the Cannes Film Festival Co-produces the film ‘’Up & Produces the “DNA” International and the International Venice Film Down – Un Film Normale‘’ film ‘Dietro la product acquisition Festival notte‘’ 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 “LA LUCIDA FOLLIA DI MARCO FERRERI” “UP&DOWN. UN FILM “NAPOLI VELATA” original “BEST REVELATION” for Fenix Entertainment • David di Donatello for Best Documentary NORMALE” Kineo award soundtrack Pasquale Catalano Anna Magnani Award to the production team • Nastro d’Argento for Best Film about Cinema for Best Social Docu-Film nominated: • David di Donatello for Best Musician • Best Soundtrack Nastri D’Argento “STIAMO TUTTI BENE” by Mirkoeilcane “DIVA!” Nastro D’Argento for the Best “UP&DOWN. -

POPULAR DVD TITLES – As of JULY 2014

POPULAR DVD TITLES – as of JULY 2014 POPULAR TITLES PG-13 A.I. artificial intelligence (2v) (CC) PG-13 Abandon (CC) PG-13 Abduction (CC) PG Abe & Bruno PG Abel’s field (SDH) PG-13 About a boy (CC) R About last night (SDH) R About Schmidt (CC) R About time (SDH) R Abraham Lincoln: Vampire hunter (CC) (SDH) R Absolute deception (SDH) PG-13 Accepted (SDH) PG-13 The accidental husband (CC) PG-13 According to Greta (SDH) NRA Ace in the hole (2v) (SDH) PG Ace of hearts (CC) NRA Across the line PG-13 Across the universe (2v) (CC) R Act of valor (CC) (SDH) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 1-4 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 5-8 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 9-12 (4v) PG-13 Adam (CC) PG-13 Adam Sandler’s eight crazy nights (CC) R Adaptation (CC) PG-13 The adjustment bureau (SDH) PG-13 Admission (SDH) PG Admissions (CC) R Adoration (CC) R Adore (CC) R Adrift in Manhattan R Adventureland (SDH) PG The adventures of Greyfriars Bobby NRA Adventures of Huckleberry Finn PG-13 The adventures of Robinson Crusoe PG The adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA An affair to remember (CC) NRA The African Queen NRA Against the current (SDH) PG-13 After Earth (SDH) NRA After the deluge R After the rain (CC) R After the storm (CC) PG-13 After the sunset (CC) PG-13 Against the ropes (CC) NRA Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The definitive collection (12v) PG The age of innocence (CC) PG Agent -

4) Sandro Bernardi, I Luoghi Del Cinema Nell'opera Di Marco Ferreri, in Stefania Parigi

SANDRO BERNARDI I LUOGHI DEL CINEMA NELL'OPERA DI FERRERI L'Occhio-Ferreri Le strade dissestate di Madrid, con i negozi decorati da insegne otto- centesche, frequentate da rari passanti e rare auto della Spagna fran- chista; la Rolls Royce con la marchesa invisibile che accompagna il fi- glio paralitico, erede delle antiche malinconie dei grandi di Spagna; i grandi palazzi del centro con i loro appartamenti stretti, caotici, so- vraffollati da gente in vestaglia: madri, suocere, figli, nipoti, cani e gat- ti, avvocatuzzi che esercitano in casa, con segretari piuttosto equivoci, nonni ficcanaso e brontoloni, buoni solo a chiedere soldi, panni stesi alle finestre o in cortile, la stalla dietro casa in pieno centro, la muc- ca che rumina placida sul cemento, galline bambini comari sfatte spor- che brontolone sparse un po' dappertutto, le camere da letto piene di santini o immagini giganti del Sacro Cuore, inquilini o inquilini degli inquilini, oppure ospiti degli inquilini degli inquilini, tutti uguali in una sola moltitudine — alla Pessoa — fantasmi che si aggirano per le case sovraffollate, vivi ma ufficialmente inesistenti, presenti ma ignorati e considerati assenti: e infine, corona di tutto lo scenario, i vecchietti pa- ralitici che in branco, quasi una parodia ante litteram dei Selvaggi cor- maniani, angeli dell'inferno un po' invecchiati, volano sulle loro car- rozzelle a motore per le strade deserte, nei parchi, nelle campagne, nei cimiteri liberty, giù per le colline che circondano la capitale sonnac- chiosa nel cuore dell'estate. Questo è il panorama dei primi due film di Ferreri El pisito e El cochecito. -

L'espace Chez Rafael Azcona, Scenariste

UNIVERSITE SORBONNE NOUVELLE – PARIS 3 École Doctorale 267 - Arts & Médias EA 1484 - Communication, Information, Médias LABEX Industries culturelles et Création artistique CEISME Centre d’Études sur les Images et Sons Médiatiques THESE REALISEE AVEC LE SOUTIEN DU LABEX ICCA Thèse de Doctorat en Sciences de l’Information et de la Communication Julia Sabina GUTIERREZ L'ESPACE CHEZ RAFAEL AZCONA, SCENARISTE Thèse dirigée par M. le Professeur François JOST Soutenue le 18 octobre 2013 Jury : M. François JOST, Professeur, Université Paris 3 Présentée et soutenue publiquement Mme. Claude MURCIA, Professeur, Université Paris 7 M. Vicente SÁNCHEZ-BIOSCA,le Professeur,18 octobre Univ2013 ersidad de Valencia Résumé Au travers de cette recherche, nous nous sommes attachée à analyser la dimension narrative des scénarii, en nous penchant plus spécifiquement sur le travail de Rafael Azcona (1926-2008), auteur de comédies pour le cinéma et la télévision. Parce qu’il a créé et exploité à l'écran un univers personnel et aisément identifiable pour les spectateurs, ce scénariste est considéré, en Espagne au moins, comme un auteur au sens plein. Notre objectif est comprendre comment un style caractéristique a pu survivre à Rafael Azcona, alors même que son texte se dissolvait peu à peu dans tout le processus de la construction d’une œuvre audiovisuelle. Ce travail analytique est d’autant plus délicat que nous devons également tenir compte du fait qu'il a collaboré avec des cinéastes aux mondes très personnels comme Marco Ferreri, Carlos Saura ou Luis García Berlanga. La principale difficulté rencontrée face au travail de Rafael Azcona était de savoir quel est le scénario original d'un film. -

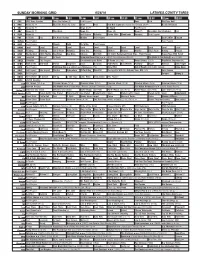

Sunday Morning Grid 6/26/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/26/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid Red Bull Signature Series From Detroit. (N) Å Beach Volleyball 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Incredible Dog Challenge Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Earth 2050 FabLab 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Happy Yoga With Sarah 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. (PG-13) The World Is Not Enough ›› (1999) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Un recuerdo para Rubé Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Firehouse Dog ›› (2007) Josh Hutcherson.