The Jazz–Flamenco Connection: Chick Corea and Paco De Lucía Between 1976 and 1982

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Dancin' on Tulsa Time

Dancin’ on Tulsa Time Gonna set my watch back to it…. 42nd ICBDA Convention July 11-14, 2018 Renaissance Hotel & Convention Center Tulsa, Oklahoma ________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Welcome to the 42nd ICBDA Convention 2018 . 1 Welcome from the Chairman of the Board . 2 Convention 43 – Orlando, Florida . 3 Committee Chairs – Convention 42 . 4 2018 Week at a Glance . 5 Cuers and Masters of Ceremony . 9 ICBDA Board of Directors . .10 Distinguished Service Award . 11 Golden Torch Award . 11 Top 15 Convention Dances . .. 12 Top 15 Convention Dances Statistics . 13 Top 10 Dances in Each Phase . 14 Hall of Fame Dances . 15 Video Order Form . 16 Let’s Dance Together – Hall A . 18 Programmed Dances – Hall A . 19 Programmed Dances – Hall B . 20 Programmed Dances – Hall C . 21 Clinic and Dance Instructors . 22 Paula and Warwick Armstrong . 23 Fred and Linda Ayres . 23 Wayne and Barbara Blackford . 24 Mike and Leisa Dawson . 24 John Farquhar and Ruth Howell . 25 Dan and Sandi Finch . 25 Mike and Mary Foral . 26 Ed and Karen Gloodt . 26 Steve and Lori Harris . 27 John and Karen Herr . 27 Tom Hicks . 28 Joe and Pat Hilton . 28 George and Pamela Hurd . 29 i ________________________________________________________________________ Pamela and Jeff Johnson . .29 John and Peg Kincaid . 30 Kay and Bob Kurczweski. 30 Randy Lewis and Debbie Olson . .31 Rick Linden and Nancy Kasznay . 31 Bob and Sally Nolen . 32 J.L. and Linda Pelton . 32 Sue Powell and Loren Brosie . 33 Randy and Marie Preskitt . 33 Mark and Pam Prow . 34 Paul and Linda Robinson . 34 Debbie and Paul Taylor . -

Physical Education Dance (PEDNC) 1

Physical Education Dance (PEDNC) 1 Zumba PHYSICAL EDUCATION DANCE PEDNC 140 1 Credit/Unit 2 hours of lab (PEDNC) A fusion of Latin and international music-dance themes, featuring aerobic/fitness interval training with a combination of fast and slow Ballet-Beginning rhythms that tone and sculpt the body. PEDNC 130 1 Credit/Unit Hula 2 hours of lab PEDNC 141 1 Credit/Unit Beginning ballet technique including barre and centre work. [PE, SE] 2 hours of lab Ballroom Dance: Mixed Focus on Hawaiian traditional dance forms. [PE,SE,GE] PEDNC 131 1-3 Credits/Units African Dance 6 hours of lab PEDNC 142 1 Credit/Unit Fundamentals, forms and pattern of ballroom dance. Develop confidence 2 hours of lab through practice with a variety of partners in both smooth and latin style Introduction to African dance, which focuses on drumming, rhythm, and dances to include: waltz, tango, fox trot, quick step and Viennese waltz, music predominantly of West Africa. [PE,SE,GE] mambo, cha cha, rhumba, samba, salsa. Bollywood Ballroom Dance: Smooth PEDNC 143 1 Credit/Unit PEDNC 132 1 Credit/Unit 2 hours of lab 2 hours of lab Introduction to dances of India, sometimes referred to as Indian Fusion. Fundamentals, forms and pattern of ballroom dance. Develop confidence Dance styles focus on semi-classical, regional, folk, bhangra, and through practice with a variety of partners. Smooth style dances include everything in between--up to westernized contemporary bollywood dance. waltz, tango, fox trot, quick step and Viennese waltz. [PE,SE,GE] [PE,SE,GE] Ballroom Dance: Latin Irish Dance PEDNC 133 1 Credit/Unit PEDNC 144 1 Credit/Unit 2 hours of lab 2 hours of lab Fundamentals, forms and pattern of ballroom dance. -

Pan-March-2020.Pdf

PANJOURNAL OF THE BRITISH FLUTE SOCIETY MARCH 2020 “This is my Flute. There are many like it, but this one is mine” Juliette Hurel Maesta 18K - Forte Headjoint pearlflutes.eu Principal Flautist of the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra contents The British Flute Society news & events 24 President 2 BFS NEWS William Bennett OBE 4 NOTES FROM THE CHAIR 6 NEWS Vice President 11 FLUTE CHOIR NEWS Wissam Boustany 13 TRADE NEWS 14 EVENTS LISTINGS Honorary Patrons 16 INTERNATIONAL EVENTS Sir James Galway 23 FLUTE CHOIR FOCUS: and Lady Jeanne Galway WOKING FLUTE CHOIR 32 Conductorless democracy in action. Vice Presidents Emeritus Atarah Ben-Tovim MBE features Sheena Gordon 24 ALEXANDER MURRAY: I’VE GONE ON LEARNING THE FLUTE ALL MY LIFE Secretary Cressida Godfrey examines an astonishing Rachel Shirley career seven decades long and counting. [email protected] 32 CASE FOR MOVEMENT EDUCATION Musicians move for a living. Kelly Mollnow 39 Membership Secretary Wilson shows them how to do it freely and [email protected] efficiently through Body Mapping. 39 WILLIAM BENNETT’S The British Flute Society is a HAPPY FLUTE FESTIVAL Charitable Incorporated Organisation Edward Blakeman describes some of the registered charity number 1178279 enticing treats on offer this summer in Wibb’s feel-good festival. Pan 40 GRADED EXAMS AND BEYOND: The Journal of the EXPLORING THE OPTIONS AVAILABLE 40 British Flute Society The range of exams can be daunting for Volume 39 Number 1 student and teacher alike. David Barton March 2020 gives a comprehensive review. 42 STEPHEN WESSEL: Editor A NATIONAL TREASURE Carla Rees Judith Hall gives a personal appreciation of [email protected] the flutemaker in the year of his retirement. -

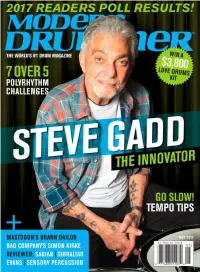

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Musica Jazz Autore Titolo Ubicazione

MUSICA JAZZ AUTORE TITOLO UBICAZIONE AA.VV. Blues for Dummies MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. \The \\metronomes MSJ/CD MET AA.VV. Beat & Be Bop MSJ/CD BEA AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Victor Jazz History vol. 13 MSJ/CD VIC AA.VV. Blue'60s MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. 8 Bold Souls MSJ/CD EIG AA.VV. Original Mambo Kings (The) MSJ/CD MAM AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 1 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. New Orleans MSJ/CD NEW AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 2 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. \Le \\grandi trombe del Jazz MSJ/CD GRA AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion two (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe III: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI AA.VV. Celebrating the music of Weather Report MSJ/CD CEL AA.VV. Night and Day : The Cole Porter Songbook MSJ/CD NIG AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe II: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball Adderley MSJ/CD ADD Aires Tango Origenes [CD] MSJ/CD AIR Al Caiola Serenade In Blue MSJ/CD ALC Allison, Mose Jazz Profile MSJ/CD ALL Allison, Mose Greatest Hits MSJ/CD ALL Allyson, Karrin Footprints MSJ/CD ALL Anikulapo Kuti, Fela Teacher dont't teach me nonsense MSJ/CD ANI Armstrong, Louis Louis In New York MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Louis Armstrong live in Europe MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Satchmo MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis -

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition by William D. Scott Bachelor of Arts, Central Michigan University, 2011 Master of Music, University of Michigan, 2013 Master of Arts, University of Michigan, 2015 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by William D. Scott It was defended on March 28, 2019 and approved by Mark A. Clague, PhD, Department of Music James P. Cassaro, MA, Department of Music Aaron J. Johnson, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Michael C. Heller, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by William D. Scott 2019 iii Michael C. Heller, PhD Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition William D. Scott, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 The term Latin jazz has often been employed by record labels, critics, and musicians alike to denote idioms ranging from Afro-Cuban music, to Brazilian samba and bossa nova, and more broadly to Latin American fusions with jazz. While many of these genres have coexisted under the Latin jazz heading in one manifestation or another, Panamanian pianist Danilo Pérez uses the expression “Pan-American jazz” to account for both the Afro-Cuban jazz tradition and non-Cuban Latin American fusions with jazz. Throughout this dissertation, I unpack the notion of Pan-American jazz from a variety of theoretical perspectives including Latinx identity discourse, transcription and musical analysis, and hybridity theory. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance

The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies Edited by K. Meira Goldberg and Antoni Pizà The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies Edited by K. Meira Goldberg and Antoni Pizà This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by K. Meira Goldberg, Antoni Pizà and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9963-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9963-5 Proceedings from the international conference organized and held at THE FOUNDATION FOR IBERIAN MUSIC, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, on April 17 and 18, 2015 This volume is a revised and translated edition of bilingual conference proceedings published by the Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Cultura: Centro de Documentación Musical de Andalucía, Música Oral del Sur, vol. 12 (2015). The bilingual proceedings may be accessed here: http://www.centrodedocumentacionmusicaldeandalucia.es/opencms/do cumentacion/revistas/revistas-mos/musica-oral-del-sur-n12.html Frontispiece images: David Durán Barrera, of the group Los Jilguerillos del Huerto, Huetamo, (Michoacán), June 11, 2011. -

A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2018-07-01 El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wilkins, Rex Richard, "El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 6997. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6997 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Brian Price, Chair Erik Larson Alvin Sherman Department of Spanish and Portuguese Brigham Young University Copyright © 2018 Rex Richard Wilkins All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Department of Spanish and Portuguese, BYU Master of Arts This thesis examines the punk genre’s evolution into commercial mainstream music in Spain and Mexico. It looks at how this evolution altered both the aesthetic and gesture of the genre. This evolution can be seen by examining four bands that followed similar musical and commercial trajectories. -

Estrella Morente Lead Guitarist: José Carbonell "Montoyita"

Dossier de prensa ESTRELLA MORENTE Vocalist: Estrella Morente Lead Guitarist: José Carbonell "Montoyita" Second Guitarist: José Carbonell "Monty" Palmas and Back Up Vocals: Antonio Carbonell, Ángel Gabarre, Enrique Morente Carbonell "Kiki" Percussion: Pedro Gabarre "Popo" Song MADRID TEATROS DEL CANAL – SALA ROJA THURSDAY, JUNE 9TH AT 20:30 MORENTE EN CONCIERTO After her recent appearance at the Palau de la Música in Barcelona following the death of Enrique Morente, Estrella is reappearing in Madrid with a concert that is even more laden with sensitivity if that is possible. She knows she is the worthy heir to her father’s art so now it is no longer Estrella Morente in concert but Morente in Concert. Her voice, difficult to classify, has the gift of deifying any musical register she proposes. Although strongly influenced by her father’s art, Estrella likes to include her own things: fados, coplas, sevillanas, blues, jazz… ESTRELLA can’t be described described with words. Looking at her, listening to her and feeling her is the only way to experience her art in an intimate way. Her voice vibrates between the ethereal and the earthly like a presence that mutates between reality and the beyond. All those who have the chance to spend a while in her company will never forget it for they know they have been part of an inexplicable phenomenon. Tonight she offers us the best of her art. From the subtle simplicity of the festive songs of her childhood to the depths of a yearned-for love. The full panorama of feelings, the entire range of sensations and colours – all the experiences of the woman of today, as well as the woman of long ago, are found in Estrella’s voice. -

Flamenco Jazz: an Analytical Study

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2016 Flamenco Jazz: an Analytical Study Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/306 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 29-77 (2016) Flamenco Jazz: An Analytical Study Peter Manuel Since the 1990s, the hybrid genre of flamenco jazz has emerged as a dynamic and original entity in the realm of jazz, Spanish music, and the world music scene as a whole. Building on inherent compatibilities between jazz and flamenco, a generation of versatile Spanish musicians has synthesized the two genres in a wide variety of forms, creating in the process a coherent new idiom that can be regarded as a sort of mainstream flamenco jazz style. A few of these performers, such as pianist Chano Domínguez and wind player Jorge Pardo, have achieved international acclaim and become luminaries on the Euro-jazz scene. Indeed, flamenco jazz has become something of a minor bandwagon in some circles, with that label often being adopted, with or without rigor, as a commercial rubric to promote various sorts of productions (while conversely, some of the genre’s top performers are indifferent to the label 1). Meanwhile, however, as increasing numbers of gifted performers enter the field and cultivate genuine and substantial syntheses of flamenco and jazz, the new genre has come to merit scholarly attention for its inherent vitality, richness, and significance in the broader jazz world.