Download Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UWL LCM Welcome to Thebes Programme 2021

BA (Hons) Acting and BA (Hons) Actor Musicianship present WELCOME TO THEBES A play by Moira Buffini London College of Music @LCMLive Streaming Online LCMLive 17 – 20 June 2021 London College of Music Director’s Note Cast and Characters After ten years of brutal civil war, When Sophocles was writing in Athens Cast Character Eurydice and her government are in the fifth century BCE, Thebes was an preparing to lead Thebes into its enemy territory. Although almost on its Lorraine Adeyefa Eurydice (Cast 1) / Helia (Cast 2) new life as a democracy. Holding the doorstep – just one day’s trek across a Christian Bludell Xenophanes (Cast 1) / Prince Tydeus (Cast 2) new-found peace by their fingertips, mountain – it was mythic and distant. A Theodoros Charalambous Tiresias they face danger on all sides. At home, point of departure in our process was to war lords seeking to profit from chaos consider the people stranded in refugee Rose De Vera Pargeia stir up rebellion, while outside their camps in Greece today: to ask who Jenna Dyckhoff Megaera / Eunomia gates, neighbouring Sparta is looking they are, where they have come from to extend its empire. Their only hope and what is our responsibility to them. Molly Evans Antigone is to secure the help of democratic Forced out, homes destroyed, they have Sophia Ford Aglaea superpower Athens. risked their lives to flee circumstances we can barely imagine, in order simply Tiana Mai Jackson Euphrosyne and Harmonia Moira Buffini relocates Oedpius’ cursed to live. During the pandemic, the Kofi Jordan Prince Tydeus (Cast 1) / Xenophanes (Cast 2) family to the twenty-first century in situation of these already vulnerable a radical reimagining of Sophocles’ people continues to worsen. -

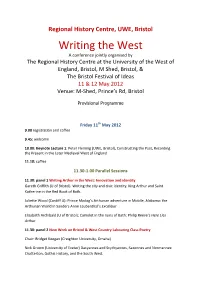

Writing the West Conference Programme

Regional History Centre, UWE, Bristol Writing the West A conference jointly organised by The Regional History Centre at the University of the West of England, Bristol, M Shed, Bristol, & The Bristol Festival of Ideas 11 & 12 May 2012 Venue: M‐Shed, Prince’s Rd, Bristol Provisional Programme Friday 11th May 2012 9.00 registration and coffee 9.45: welcome 10.00: Keynote Lecture 1: Peter Fleming (UWE, Bristol), Constructing the Past, Recording the Present in the Later Medieval West of England 11.10: coffee 11.30‐1.00 Parallel Sessions 11.30: panel 1 Writing Arthur in the West: Innovation and identity Gareth Griffith (U of Bristol): Writing the city and civic identity: King Arthur and Saint Katherine in the Red Book of Bath. Juliette Wood (Cardiff U): Prince Madog’s Arthurian adventure in Mobile, Alabama: the Arthurian World in Sanders Anne Laubenthal’s Excalibur Elizabeth Archibald (U of Bristol): Camelot in the ruins of Bath: Philip Reeve’s Here Lies Arthur 11.30: panel 2 New Work on Bristol & West Country Labouring Class Poetry Chair: Bridget Keegan (Creighton University, Omaha) Nick Groom (University of Exeter) Dacyannes and Scythyannes, Saxonnes and Normannes: Chatterton, Gothic History, and the South West. Kerri Andrews, (Strathclyde University), Ann Yearlsey, a Bristol Poet. John Goodridge (Nottingham Trent), John Gregory: sonnets, shoemaking and socialism 1.00pm Lunch 2.00‐3.30 Parallel Sessions 2.00‐3.30 panel 1: Landscape, Nature and Place Dave Postles (University of Leicester) Trickster in the Wiltshire landscape: E. M. Forster and The Longest Journey Richard Coates (UWE, Bristol) ‘Bent on emptying his note‐book in decent English’: Richard Jefferies, naturalistic observation, and English dialect. -

The Mirror Crack'd

PRESS RELEASE – Friday 23rd November IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE @theCentre / Facebook / Instagram / www.wmc.org.uk @wiltscreative / Facebook / Instagram / www.wiltshirecreative.co.uk A Wales Millennium Centre and Wiltshire Creative Production THE MIRROR CRACK’D by Agatha Christie adapted for the stage by Rachel Wagstaff Direction by Melly Still Set Design by Richard Kent Costume Design by Dinah Collin Lighting Design by Malcolm Rippeth Music & Sound Design by Jon Nicholls Movement by Joseph Alford • CASTING HAS BEEN ANNOUNCED FOR THE FIRST EVER UK STAGE ADAPTATION OF AGATHA CHRISTIE’S THE MIRROR CRACK’D • THE WALES MILLENNIUM CENTRE AND WILTSHIRE CREATIVE EUROPEAN PREMIERE PRODUCTION WILL TOUR FROM FEBRUARY 2019, WITH AN OPENING NIGHT AT SALISBURY PLAYHOUSE ON 25 FEBRUARY 2019 • TICKETS ARE NOW ON SALE Wales Millennium Centre and Wiltshire Creative have today announced casting for the first ever UK stage adaptation of Agatha Christie’s much-loved Miss Marple thriller The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side. Colin R Campbell, Suzanna Hamilton, Julia Hills, Katherine Manners, Katie Matsell, Davina Moon, Huw Parmenter and Gillian Saker will join the previously announced Susie Blake and Simon Shepherd. The Mirror Crack’d will be a European Premiere, opening at Salisbury Playhouse on 15 February before touring to Dublin, Cambridge and Cardiff. The Mirror Crack’d will have an Opening Night on 25 February. The iconic Marple mystery from the world’s best-selling author of all time has been adapted for the stage by Rachel Wagstaff (Flowers for Mrs Harris, Birdsong) and directed by Melly Still (Coram Boy, My Brilliant Friend, The Lovely Bones). -

Salisbury Playhouse Salisbury Arts Centre Spring/Summer 2019 Season

SALISBURY PLAYHOUSE SALISBURY ARTS CENTRE SPRING/SUMMER 2019 SEASON THEATRE | DANCE | MUSIC | COMEDY | FILM | EXHIBITIONS | WORKSHOPS | CAFÉS www.wiltshirecreative.co.uk Ticket Sales 01722 320333 1 CONTENTS WELCOME 3 SEE MORE, PAY LESS 4 – 5 FEST WEST 2019 6 SALISBURY INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 7 ONE NIGHT EVENTS AT SALISBURY PLAYHOUSE 8 – 10 SALISBURY PLAYHOUSE | MAIN HOUSE 11 – 22 SALISBURY PLAYHOUSE | THE SALBERG 23 – 33 SALISBURY ARTS CENTRE 34 LIVE MUSIC 35 – 39 THEATRE & DANCE 40 – 43 COMEDY 44 – 45 SILVER SCREEN WEDNESDAY MATINEES 46 FILM NIGHTS 47 LIVE SCREENINGS 48 – 49 VISUAL ARTS EXHIBITIONS 50 – 51 TAKE PART 52 – 53 WORKSHOPS 54 – 58 BECOME A MEMBER & PARTNER WITH US 59 PRICING 60 – 61 EVENT DIARY 62 – 65 2 WELCOME Welcome to the Spring 2019 Season at Salisbury Playhouse and Salisbury Arts Centre. At Salisbury Playhouse we are thrilled to be working with Wales Millennium Centre to produce the first stage production of Agatha Christie’s The Mirror Crack’d (premiering here prior to a national tour) and with York Theatre Royal on a new production of the razor-sharp comedy about The Queen and Mrs Thatcher, Handbagged. We are also delighted to be presenting Barney Norris’s new adaptation of The Remains of the Day, the welcome return of Around the World in 80 Days (prior to a U.S. tour) and Northern Broadsides’ production of Much Ado About Nothing. At Salisbury Arts Centre there’s a packed programme of music, theatre, film, visual art and more, including music from Nick Harper, Cara Dillon and Girls Only Jazz Orchestra, dance from Rosie Kay and Yorke Dance and comedy from Alfie Moore and Stuart Goldsmith. -

The Sound of William Barnes's Dialect Poems

Welcome to the electronic edition of The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems: 3. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, third collection (1862). The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems 3. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, third collection About this volume This is the third volume in a series that sets out to provide a phonemic transcript and an audio recording of each individual poem in Barnes’s three collections of Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect. Its 96 poems include some of those most loved and admired: poems of heart-wrenching grief at the untimely deaths of Barnes’s wife, Julia (“Woak Hill”), and their young son, Julius “The turnstile”); celebrations of love anticipated (“In the spring”) and love fulfilled (“Don’t ceäre”); protests against injustice and snobbery (“The love child”); struggles to accept God’s will (“Grammer a-crippled”); comic poems (“John Bloom in Lon’on”, “A lot o’ maïdens a-runnèn the vields”); and poems on numerous other subjects, with an emotional range stretching from the deepest of grief to the highest of joy. The metrical forms show astonishing versatility, from straightforward octosyllabic couplets to challenging rhyme-schemes and innovative stanzaic patterns, widely varied line-lengths, and skilful adaptations of rhetorical devices from other languages. -

The Sound of William Barnes's Dialect Poems

Welcome to the electronic edition of The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems: 2. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, second collection (1859). The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems 2. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, second collection About this volume This is the second volume in a series that sets out to to provide a phonemic transcript and an audio recording of each individual poem in Barnes’s three collections of Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect. Beginning with two poems that inspired Vaughan Williams to set them to music, and ending with a paean of praise for the poet’s native county, this second collection contains 105 poems of immense range and power. There are poems of longing, of love and of loss; of pain and of protest; of tears and of laughter; of grief and consolation; of feasting and celebration; of music and birdsong; of falsehood and friendship and faith; of generosity and meanness; of bad temper and good; of stasis and travel; of flowers and trees; of storm and of calm. “Here,” in short, (as Dryden famously said of the poetry of Geoffrey Chaucer) “is God’s plenty”. -

Reference Guide for Varieties of English 1 General

Reference guide for varieties of English Outline structure 1 General 1.1 Investigating variation 1.1 Language change 1.2 Standard English 1.4 Nonstandard English 1.5 Historical background 2 England 2.1 Overviews 2.2 Received Pronunciation 2.3 Estuary English 2.4 Cockney 2.5 British Creole 2.6 East Anglia 2.7 South of England 2.8 West and South-West 2.9 Northern English 2.10 Other languages in Britain 3 The Celtic realms 3.1 Scotland 3.2 Wales 3.3 Ireland 3.4 Isle of Man 4 Minor European varieties 4.1 Channel Islands 4.2 Gibraltar 4.3 Malta 5 The New World 5.1 American English 5.2 Canadian English 5.3 Caribbean English 6 English in Africa 6.1 West Africa 6.2 East Africa 6.3 Southern Africa 6.4 The South Atlantic 7 English in Asia 7.1 South Asia 7.2 South-East Asia 7.3 East Asia 8 Australasia and Pacific 8.1 Australia 8.2 New Zealand 8.3 The anglophone Pacific 9 English-based pidgins and creoles 10 World Englishes 10.1 English and colonialism 10.2 ‘New Englishes’ 10.3 Nonnative Englishes 1 General Aarts, Bas and April McMahon (eds) 2006. The Handbook of English Linguistics. Oxford / Malden, MA: Blackwell. Allen, Harold B. and Michael D. Linn (eds) 1986. Dialect and Language Variation. Orlando: Academic Press. Anderson, Peter M. 1987. A Structural Atlas of the English Dialects. London. Raymond Hickey Reference guide for varieties of English Page 2 of 61 Auer, Peter, Frans Hinskens and Paul Kerswill (eds) 2000. -

Contemporary Antigones, Medeas and Trojan Women

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository CONTEMPORARY ANTIGONES, MEDEAS AND TROJAN WOMEN PERFORM ON STAGES AROUND THE WORLD by OLGA KEKIS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Drama and Theatre Arts School of English, Drama, and American and Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham February 2013 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines postmodern theatrical adaptations of Antigone, Medea and The Trojan Women to show how they re-define the central female figures of the source texts by creating a new work, or ‘hyperplay’, that gives the silenced and often silent female figures a voice, and assigns them a political presence in their own right. Using a collection of diverse plays and their performances which occurred in a variety of geographical locations in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, this thesis analyzes adaptive, ‘hypertheatrical’, strategies employed by the theatre, through which play texts from the past are ‘re-made’ in the here and now of theatrical performances. -

A History of the Welsh English Dialect in Fiction

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses A History of the Welsh English Dialect in Fiction Jones, Benjamin A. How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Jones, Benjamin A. (2018) A History of the Welsh English Dialect in Fiction. Doctoral thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa44723 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ A history of the Welsh English dialect in fiction Benjamin Alexander Jones Submitted to Swansea University in fulfilment of the requirements -

Dialect, Adaptation and Assimilation in the Poetry of William Barnes and Thomas Hardy

Dialect, Adaptation and Assimilation in the Poetry of William Barnes and Thomas Hardy Heather Hawkins* The Dorset poets William Barnes and Thomas Hardy lived during a period of great social and economic change in nineteenth-century Britain, change triggered by enclosure and the gradual machinisation of farming. This caused the rapid disappearance of rural culture, something of which Barnes and Hardy would have been acutely aware, as both of their families occupied an ambiguous class position; though elevated from the majority of the labouring class by their employment and education, they were not wealthy enough to join the middle class. A close reading of Barnes’s poem ‘Woak Were Good Enough Woonce’ and Hardy’s poem ‘Silences’ illustrates the poets’ contrasting approaches to dialect in poetry, and reveals their different responses to the effects of the increased urbanisation of rural culture. In particular, an examination of the use of dialect in these poems offers interesting insights into the processes of cultural adaptation and assimilation which were brought about by such changes. The enclosure of land in the early 1800s and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 forced many small tenant farmers out of business, and led to an increase in rural unemployment and a subsequent migration of labourers to urban centres. This influx of workers indicated the ability of the rural labourer to adapt to social and economic change.1 However, the rural labourer, or ‘Hodge’ as he was dubbed by social commentators of the period, was typically presented in contemporary literature as slow, awkward, lacking in social ambition and only able to converse in an unintelligible language. -

A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova

A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova EDINBURGH TEXTBOOKS ON THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE – ADVANCED A Historical Phonology of English Edinburgh Textbooks on the English Language – Advanced General Editor Heinz Giegerich, Professor of English Linguistics, University of Edinburgh Editorial Board Laurie Bauer (University of Wellington) Olga Fischer (University of Amsterdam) Rochelle Lieber (University of New Hampshire) Norman Macleod (University of Edinburgh) Donka Minkova (UCLA) Edgar W. Schneider (University of Regensburg) Katie Wales (University of Leeds) Anthony Warner (University of York) TITLES IN THE SERIES INCLUDE: Corpus Linguistics and the Description of English Hans Lindquist A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova A Historical Morphology of English Dieter Kastovsky Grammaticalization and the History of English Manfred Krug and Hubert Cuyckens A Historical Syntax of English Bettelou Los English Historical Sociolinguistics Robert McColl Millar A Historical Semantics of English Christian Kay and Kathryn Allan Visit the Edinburgh Textbooks in the English Language website at www. euppublishing.com/series/ETOTELAdvanced A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova © Donka Minkova, 2014 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9LF www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 10.5/12 Janson by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 3467 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 3468 2 (paperback) ISBN 978 0 7486 3469 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 7755 9 (epub) The right of Donka Minkova to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

327 Language Peculiarities of Regional British English

LANGUAGE PECULIARITIES OF REGIONAL BRITISH ENGLISH VARIANTS S. A. Shurko Belarusian State University, Niezaliežnasci Avenue, 4, 220030, Minsk, Republic of Belarus, shurko.bsu.by Language accents and dialects are factors which sometimes may lead to misunderstand- ing between people speaking one and the same language but living in different areas and dis- tricts. The purpose of this article is to outline the differences of the regional dialects from the standard and to underline characteristic features peculiar only for them. In this paper we have analyzed the speech of people who live in the UK on the examples of the speakers of British dialects and accents which were taken from the video film called ―Language accent file‖. We have traced the differences and made a conclusion that every single accent or dia- lect possesses a number of features which could only be heard in a definite area or among par- ticular class representatives. This article reflects the factors influencing the way people speak, such as geographical area people were born in and raised, their education, age and class deline- ation which is still strong in Great Britain. Keywords: dialects; accents; rhotic language; glottal stop; h-dropping; double negation; re- duction; syllables merger. ЯЗЫКОВЫЕ ОСОБЕННОСТИ РЕГИОНАЛЬНЫХ ВАРИАНТОВ БРИТАНСКОГО АНГЛИЙСКОГО С. А. Шурко Белорусский государственный университет, Незележнасти пр, 4, 220030, Минск, Республика Беларусь, shurko.bsu.by Языковые акценты и диалекты являются факторами, которые иногда могут приве- сти к недопониманию между людьми, говорящими на одном и том же языке, но живу- щими в разных районах. Цель данной статьи - выделить отличия региональных диалек- тов от общепринятых и подчеркнуть характерные черты, свойственные только им.