Urban Planning and the Development of Tehran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample File P’ A Karachi S T Demavend J Oun to M R Doshan Tappan Muscatto Kand Airport

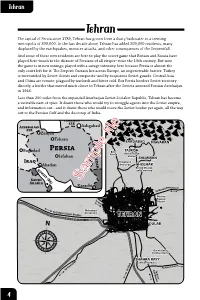

Tehran Tehran Tehran The capital of Persia since 1789, Tehran has grown from a dusty backwater to a teeming metropolis of 800,000. In the last decade alone, Tehran has added 300,000 residents, many displaced by the earthquakes, monster attacks, and other consequences of the Serpentfall. And some of these new residents are here to play the secret game that Britain and Russia have played here–much to the distaste of Persians of all stripes–since the 19th century. But now the game is in new innings; played with a savage intensity here because Persia is almost the only court left for it. The Serpent Curtain lies across Europe, an impenetrable barrier. Turkey is surrounded by Soviet clients and conquests–and by suspicious Soviet guards. Central Asia and China are remote, plagued by warlords and bitter cold. But Persia borders Soviet territory directly, a border that moved much closer to Tehran after the Soviets annexed Persian Azerbaijan in 1946. Less than 200 miles from the expanded Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, Tehran has become Tbilisia veritable nest of spies. It draws those who would try to smuggle agents into the Soviet empire, and information out…and it draws those who would move the Soviet border yet again, all the way out to the PersianBaku Gulf and the doorstep of India.Tashkent T Stalinabad SSR A Ashgabad SSR Zanjan Tehran A S KabulSAADABAD NIAVARAN Damascus Baghdad P Evin TAJRISH Prison Red Air Force Isfahan Station SHEMIRAN I Telephone Jerusalem Abadan Exchange GHOLHAK British Mission and Cemetery R S Sample file P’ A Karachi S t Demavend J oun To M R Doshan Tappan MuscatTo Kand Airport Mehrabad Jiddah To Zanjan (Soviet Border) Aerodrome BombayTEHRAN N O DULAB Gondar A A Aden S Qul’eh Gabri Parthian Ruins SHAHRA RAYY Medieval Ruins To Garm Sar Salt Desert To Hamadan To Qom To Kavir 4 Tehran Tehran THE CHARACTER OF TEHRAN Tehran sits–and increasingly, sprawls–on the southern slopes of the Elburz Mountains, specifically Mount Demavend, an extinct volcano that towers 18,000 feet above sea level. -

IRAN COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

IRAN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 28 June 2011 IRAN JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN FROM 14 MAY TO 21 JUNE Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 14 MAY AND 21 JUNE Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.04 Iran ..................................................................................................................... 1.04 Tehran ................................................................................................................ 1.05 Calendar ................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Pre 1979: Rule of the Shah .................................................................................. 3.01 From 1979 to 1999: Islamic Revolution to first local government elections ... 3.04 From 2000 to 2008: Parliamentary elections -

General Overview of Iran Dietary Supplements Market

INDEX INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................3 GENERAL OVERVIEW OF IRAN DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS MARKET ..........................................................................4 VARIETY OF DSs PRODUCTION IN IRAN ..................................................................................................................5 OPPORTUNITIES IN DSs PRODUCTION IN IRAN ......................................................................................................6 TOTAL SUPPLEMENT PRODUCTION IN IRAN ..........................................................................................................7 TRADE WITH ITALY ..................................................................................................................................................8 ITALIAN PRESENCE IN IRAN ....................................................................................................................................9 IRAN REGISTRATION CODE “IRC” ISSUANCE STEPS ............................................................................................. 10 SOME IMPORTANT TIPS ABOUT OBTAINING IRC ................................................................................................ 11 LIST OF IRANIAN FOOD SUPPLEMENTS IMPORTERS ........................................................................................... 12 THE RELATED TRADE FAIRS OF FOOD AND DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS IN IRAN .................................................... -

Emam Khomeini

yÄo\U / Tajrish 1 1 ﻗﯿﻄﺮﯾﻪ ﺷﻬﯿﺪ ﻣﺤﻼﺗﯽ Gheytariyeh Shahid Mahallati ﺷﻬﯿﺪ ﺻﺪر Shahid Sadr / 3 jIùM¼º 3 ¤GI´ اﻗﺪﺳﯿﻪ ﻗﻠﻬﮏ Gholhak Nobonyad Aghdasiyeh Gha’em ﺣﺴﯿﻦ آﺑﺎد دﮐﺘﺮ ﺷﺮﯾﻌﺘﯽ Doctor Shari'ati Hossein Abad ﻧﻘﺸﻪ راه آﻫﻦ ﺷﻬﺮي ﺗﻬﺮان و ﺣﻮﻣﻪ - ﻣﺘﺮو ﻣﯿﺪان ﻫﺮوي ﻣﯿﺮداﻣﺎد Tehran Urban & Suburban Railway (Metro) Map Mirdamad Meydan-e Heravi ﺷﻬﯿﺪ زﯾﻦ اﻟﺪﯾﻦ Shahid Zeynoddin ﺷﻬﯿﺪ ﺣﻘﺎﻧﯽ ﺧﻮاﺟﻪ ﻋﺒﺪاﷲ اﻧﺼﺎري Shahid Haghani Khajeh Abdollah-e Ansari ﺷﻬﯿﺪ ﻫﻤﺖ ﺷﻬﯿﺪ ﺻﯿﺎد ﺷﯿﺮازي Shahid Hemmat Shahid sayyad-e Shirazi داﻧﺸﮕﺎه ﻋﻠﻢ و ﺻﻨﻌﺖ ره Daneshgah-e Elm-o San’at ﻣﺼﻠﯽ اﻣﺎم ﺧﻤﯿﻨﯽ ﺗﻬﺮاﻧﭙﺎرس ﺷﻬﯿﺪ ﻗﺪوﺳﯽ Mosalla-ye Emam Khomeini Shahid Ghodousi (Elm-o San’at University) ﺳﺮﺳﺒﺰ }¿ÂTz¿M kà Sarsabz / 2 ﻣﯿﺮزاي ﺷﯿﺮازي o¿z±¬ qLw ³nH (¾Ã¤jIÅ) ·Ho¿U Mirza-ye Shirazi Shahid Beheshti 2 ﭼﯿﺘﮕﺮ وردآورد اﺗﻤﺴﻔﺮ ﻣﺤﻤﺪ ﺷﻬﺮ Hov«¹ÀoÎ ﺷﻬﯿﺪ ﺑﺎﻗﺮي (Golshahr Mohammad Shahr Atmosfer Vardavard Chitgar Eram-e Sabz Tehran (Sadeghiyeh Shahid Bagheri Farhangsara ﻣﯿﺪان ﺟﻬﺎد ﺟﺎﻧﺒﺎزان Meydan-e Jahad Janbazan ﺳﻬﺮوردي / 5 5 Sohrevardi ﻓﺪكFadak ﺷﻬﯿﺪ ﻣﻔﺘﺢ ø] اﯾﺮان ﺧﻮدرو o~ø ²» Roñe ·Hkö Shahid Mofatteh ورزﺷﮕﺎه آزادي ﮔﺮم دره ﮐﺮج Karaj Garmdarreh Iran Khodro Varzeshgah-e Azadi Meydan-e Hazrat-e Vali Asr ﺳﺒﻼن (Azadi Sport Complex) oÃU ´TÿÀ ÁHk¿{ Sabalan ﻃﺮﺷﺖ Tarasht Shohada-ye Haftom-e Tir ﺷﻬﺮك اﮐﺒﺎﺗﺎن ﺷﻬﯿﺪ ﻣﺪﻧﯽ Shahrak-e Ekbatan Shahid Madani ﻃﺎﻟﻘﺎﻧﯽ µÃM¾ Ãve ³I¶H¸ع Taleghani داﻧﺸﮕﺎه ﺷﺮﯾﻒ Bimeh Daneshgah-e Sharif ·I¶jI{ kÃe¼U o¿{ oUIFU Emam Hossein ﻓﺮدوﺳﯽ Sharif University) Shademan) Towhid Teatr-e Shahr Ferdowsi (City Theatre) ·Hoõ{ ½pH»nj S²»j ½pH»nj Darvazeh Shemiran Darvazeh Dowlat ﻣﯿﺪان اﻧﻘﻼب اﺳﻼﻣﯽ -

Migrations and Social Mobility in Greater Tehran: from Ethnic Coexistence to Political Divisions?

Migrations and social mobility in greater Tehran : from ethnic coexistence to political divisions? Bernard Hourcade To cite this version: Bernard Hourcade. Migrations and social mobility in greater Tehran : from ethnic coexistence to political divisions?. KUROKI Hidemitsu. Human mobility and multi-ethnic coexistence in Middle Eastern Urban societies1. Tehran Aleppo, Istanbul and Beirut. , 102, Research Institute for languages and cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Languages, pp.27-40, 2015, Studia Culturae Islamicae, 978-4-86337-200-9. hal-01242641 HAL Id: hal-01242641 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01242641 Submitted on 13 Dec 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS Bernard Hourcade is specializing in geography of Iran and Research Director Emeritus of Le Centre national de la recherche scientifique. His publication includes L'Iran au 20e siècle : entre nationalisme, islam et mondialisation (Paris: Fayard, 2007). Aïda Kanafani-Zahar is specializing in Anthropology and Research Fellow of Le Centre national de la recherche scientifique, affiliating to Collège de France. Her publication includes Liban: le vivre ensemble. Hsoun, 1994-2000 (Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 2004). Stefan Knost is specializing in Ottoman history of Syria and Acting Professor of Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

In the Name of God HISTORY

In The Name of God HISTORY The Packman Company was established in February 1975. In that year it was also registered in Tehran›s Registration Department. Packman›s construction and services company was active in building construction and its services in the early years of its formation.In 1976 in cooperation with (Brown Boveri and Asseck companies) some power plant mega projects was set up by the compa- ny.The company started its official activity in the filed of construction of High-Pressure Vessels such as Hot-Water Boilers , Steam Boilers , Pool Coil Tanks Softeners and Heat Exchangers from 1984. Packman Company was one of the first companies which supplied its customers with hot- water boilers which had the quality and standard mark.Packman has been export- ing its products to countries such as Uzbekistan, United Arab Emirates and other countries in the region. It is one of the largest producers of hot-water and steam boilers in the Middle East. Packman Company has got s degree from the Budget and Planning Organization in construction and services in the membership of some important associations such as: 1. Construction Services Industry Association 2. Industry Association 3. Construction Companies› Syndicate 4.Technical Department of Tehran University›s Graduates Association 5. Mechanical Engineering Association 6. Engineering Standard Association Packman Product: Steam boiler ( Fire tube ) Hot water boiler ( Fire tube ) Combination boile Water pack boiler Steam boiler ( water tube ) Hot water boiler (water tube) Boiler accessories Pressure vessel Water treatment equipment SOME OF CERTIFICATION ARE Manufacturer of Boilers, Thermal Oil Heaters, Heat Exchangers, Pressure Vessels, Storage Tanks & Industrial Water Treatment Equipments ,.. -

Iran Chamber of Commerce,Industries and Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 1

Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 1 Activity type: Exports , State : Tehran Membership Id. No.: 11020060 Surname: LAHOUTI Name: MEHDI Head Office Address: .No. 4, Badamchi Alley, Before Galoubandak, W. 15th Khordad Ave, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: 1191755161 Email Address: [email protected] Phone: 55623672 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11020741 Surname: DASHTI DARIAN Name: MORTEZA Head Office Address: .No. 114, After Sepid Morgh, Vavan Rd., Qom Old Rd, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 0229-2545671 Mobile: Fax: 0229-2546246 Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11021019 Surname: JOURABCHI Name: MAHMOUD Head Office Address: No. 64-65, Saray-e-Park, Kababiha Alley, Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5639291 Mobile: Fax: 5611821 Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11021259 Surname: MEHRDADI GARGARI Name: EBRAHIM Head Office Address: 2nd Fl., No. 62 & 63, Rohani Now Sarai, Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: 14611/15768 Email Address: [email protected] Phone: 55633085 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11022224 Surname: ZARAY Name: JAVAD Head Office Address: .2nd Fl., No. 20 , 21, Park Sarai., Kababiha Alley., Abbas Abad Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5602486 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Center (Computer Unit) Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 2 Activity type: Exports , State : Tehran Membership Id. No.: 11023291 Surname: SABBER Name: AHMAD Head Office Address: No. 56 , Beside Saray-e-Khorram, Abbasabad Bazaar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5631373 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11023731 Surname: HOSSEINJANI Name: EBRAHIM Head Office Address: .No. -

Iran March 2009

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT IRAN 17 MARCH 2009 UK Border Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE IRAN 17 MARCH 2009 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN, FROM 2 FEBRUARY 2009 TO 16 MARCH 2009 REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 2 FEBRUARY 2009 TO 16 MARCH 2009 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ......................................................................................... 1.01 Maps .............................................................................................. 1.03 Iran............................................................................................. 1.03 Tehran ....................................................................................... 1.04 2. ECONOMY ............................................................................................ 2.01 Sanctions ...................................................................................... 2.13 3. HISTORY ............................................................................................... 3.01 Calendar ........................................................................................ 3.02 Pre 1979......................................................................................... 3.03 1979 to 1999 .................................................................................. 3.05 2000 to date................................................................................... 3.16 Student unrest ............................................................................. -

Alphabetical List

ALPHABETICAL LIST 122 123 ALPHABETICAL LIST A I Pages 115 to 158 Pages 281 to 300 B J Pages 158 to 181 Pages 300 to 310 C K Pages 181 to 196 Pages 310 to 331 D L Pages 196 to 212 Pages 331 to 337 E M Pages 212 to 226 Pages 337 to 361 F N Pages 226 to 250 Pages 361 to 379 G O Pages 250 to 261 Pages 379 to 386 H P Pages 261 to 281 Pages 386 to 442 124 Q Y Pages 442 to 444 Pages 556 to 557 R Z Pages 444 to 459 Pages 557 to 560 S Pages 459 to 515 T Pages 515 to 541 U Pages 541 V Pages 541 W Pages 541 to 548 X Pages 548 to 556 125 2MKABLO DIŞ TICARET VE Mehmet Dereli PAZARLAMA A.Ş. Field of activity: able Manufacturer- Special cables- Fire resistant/Halogen SANCAKTEPE MAH, KLAS ALLEY, NO: free Flame retardant cables (LPCB)(IEC 60331, BS 6387 CWZ 8, SILIVRI-ISTANBUL» EN 50200, EN 50362, IEC 60332-3) Instrumentation cables (PVC, PVC-HR, PVC-O, UV resistant, Fire resistant), Marine and Shipboard cables, Control cables, Cathodic Protection cables, Railway cables, Bus cables,.. Tel: 0098-02122228250 Fax: 9.02122E+11 www.2mkablo.com Hall: 38B [email protected], Stand: 2552 [email protected] 3P PRINZ SRL Mrs. Silvia Marianetti Field of activity: Positive Displacement Pumps Manufacturing «Via Enrico Mattei293/R,Mugnano, 55100 Lucca» Tel: +39 0583 491183 Fax: +39 0583 954659 www.3pprinz.com Hall: 38B [email protected] Stand: 2442 3R SOLUTIONS Georg Schulze-Dürr Field of activity: 3R offers a piping software framework and pipe-shop Kleistrasse 39 59073 Hamm Germany turnkey projects. -

President Gives Europe Two More Months to Save JCPOA

Iranian Authorities Released on The European Union Reportedly Humanitarian Grounds Seven of the Urged Iran on Wednesday 23 Crew Members – Five Indians, To Refrain From Steps That One Latvian and One Russian - on Could Undermine the Nuclear A Detained British-Flagged Oil Deal as Iran Is to Reduce Its Tanker, Stena Impero Commitments to the JCPOA VOL. XXV, No. 6764 TEHRAN Price 20,000 Rials www.irannewsdaily.com THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, - SHAHRIVAR 14, 1398 2 4 8 DOMESTIC 3 DOMESTIC INTERNATIONAL SPORTS Resistance Sapping Yazd Ready to Host U.S., France, Britain Dimitrov Stuns Federer U.S., Israeli ECO Traders at May Be Complicit in Power in Region ECOFAR Exhibition Yemen War Crimes To Reach U.S. Open Semis > SEE PAGE 2 > SEE PAGE 3 > SEE PAGE 4 > SEE PAGE 8 Zarif Dismisses U.S. Space-Agency President Gives Europe Two Iran Rejects European Sanctions as “Totally Ineffective” Union’s $15b Offer as Loan TEHRAN (Dispatches) - Iran’s foreign minister has More Months to Save JCPOA TEHRAN (Dispatches) - Iran has rejected the European accused the United States of an overreliance on Union’s offer to provide it a $15 billion loan and will sanctions and said the latest punitive measures out of only stop scrapping its obligations under the nuclear Washington targeting his country’s space and research deal if it sells as much oil as it used to before sectors are “totally ineffective.” Washington’s sanctions, Press TV reported on “Americans are addicted to sanctions. These sanctions Wednesday, as Iran is expected to announce its third are totally ineffective,” Foreign Minister Mohammad retaliatory step on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Javad Zarif was quoted by the semiofficial Tasnim news Action (JCPOA) agency as saying on September 4 in the first public Meanwhile, Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas reaction to the U.S. -

Prospects for Iran's 2009 Presidential Elections

The Middle East Institute Policy Brief No. 24 June 2009 Prospects for Iran’s 2009 Presidential Elections By Walter Posch The tenth Iranian presidential elections once again expose the deep political and ideological rift between reformists and non-reformists. However, even more dramat- ic changes took place within the two political “camps.” After having been sidelined for years, the non-reformist right has successfully re-invented itself as “osulgara” — fundamentalists. However, the path towards developing an efficient party is blocked thanks to a severe bifurcation within the right between followers and opponents of the incumbent President, Mahmud Ahmadinejad, who has lost nothing of his out- sider and underdog image. On the reformists’ side, the old and actually successful alliance between moderate right and democratic-Islamist groups has found a new frontman, former Prime Minister Mir Hossein Moussavi-Khamene. His flirtations with fundamentalist tenets are both a testimony to the increasingly ideologized po- litical atmosphere in the country and a smart move to garner votes from the anti- Ahmadinejad elements within the Islamic right while at the same time inoculating the reformist movement against accusations to be essentially counterrevolutionary. Thus a close race can be expected. For more than 60 years, the Middle East Institute has been dedicated to increasing Americans’ knowledge and understanding of the re- gion. MEI offers programs, media outreach, language courses, scholars, a library, and an academic journal to help achieve its goals. The views expressed in this Policy Brief are those of the author; the Middle East Institute does not take positions on Middle East policy.