Spokes-Character Usage As a Marketing Tool on Twitter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automatic Payroll Deduction Program

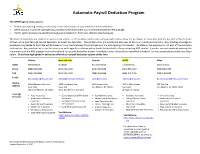

Automatic Payroll Deduction Program The APD Program allows you to: • Review participating vendor product and service information at your worksite on non-work time. • Select optional insurance coverage not provided by the State under your current employee benefit package. • Pay for optional insurance benefits through payroll deduction from your after tax take home pay. The State of Iowa does not endorse or sponsor any vendor, or the products and services they provide, it does allow the premiums for insurance policies, not offered by the State of Iowa, to be paid through payroll deduction as a post tax deduction. Payroll deduction is a simple and easy way to pay your insurance premiums. Any resulting coverage an employee may decide to purchase will be based on a contract between the employee and the participating APD vendor. The State as the employer is not part of the insurance relationship. Any questions or issues that may arise with regard to a chosen policy should be directed to the participating APD vendor. A vendor can participate by meeting the requirements of the APD program but not be offered as a payroll deduction option if enrollment does not meet the mandated threshold. Current participating vendors are listed below. Only those highlighted in yellow are offered as a payroll deduction option at this time. Allstate New York Life Colonial AFLAC Allied Agent Betty Bebout Jay Black Richard Ginther Todd DeVoss Daryl Johnson Phone (888) 584-8322 (515) 453-1328 (515) 205-9660 (312) 870-1007 (800) 982-0756 FAX (515) 225-8030 (515) 453-1490 (888) 361-6656 (888) 242-7108 (800) 548-8289 E-mail [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mailing 3636 Westown Parkway 4900 University Ave. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-07434 Aflac Incorporated (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Georgia 58-1167100 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 1932 Wynnton Road Columbus Georgia 31999 (Address of principal executive offices) (ZIP Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: 706.323.3431 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbols(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $.10 Par Value AFL New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. þ Yes ¨ No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. ¨ Yes þ No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Twitter: a Uses and Gratifications Approach

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 “WHAT’S HAPPENING” @TWITTER: A USES AND GRATIFICATIONS APPROACH Corey Leigh Ballard University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ballard, Corey Leigh, "“WHAT’S HAPPENING” @TWITTER: A USES AND GRATIFICATIONS APPROACH" (2011). University of Kentucky Master's Theses. 155. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_theses/155 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF THESIS “WHAT’S HAPPENING” @TWITTER: A USES AND GRATIFICATIONS APPROACH The uses and gratifications approach places power in the hands of the audience and is a helpful perspective when trying to understand media usage, exposure, and effects. However, while the uses and gratifications approach has been applied regularly to traditional media, research explaining why people use new social media networks as well as the gratifications they obtain from them is scarce at best. This thesis provides a comprehensive overview of the uses and gratifications approach as well as the current literature about social media networks. An argument is built within the thesis to study Twitter as one social media network through the uses and gratifications theoretical lens. Research questions are provided and a survey of 216 college undergraduates was conducted. Results show that people use a variety of Twitter functions, that the gratifications sought from Twitter are not the gratifications obtained from Twitter, and that people are careful about the types of information they share on the social media network. -

AFLAC U.S. Strong Sales Propel AFLAC to Record Year

AFLAC U.S. Strong Sales Propel AFLAC to Record Year 2000 was a year to remember for AFLAC U.S. for • Premium income rose 14.4% to $1.6 billion, up from many reasons. We added to our product line and $1.4 billion in 1999. significantly expanded our sales force. We also • Net investment income increased 13.2% to $277 million, introduced the most successful advertising campaign compared with $245 million in 1999. in our history. As a result, new sales rose to record levels and revenue growth accelerated. Below are • Total revenues were up 14.3%, rising from $1.6 billion in some highlights for the year: 1999 to $1.8 billion in 2000. • New annualized premium sales increased 28.3% to • Pretax operating earnings grew 13.3% to $290 million, $712 million, compared with $555 million in 1999. compared with $256 million in 1999. Mitchell Odendahl, 2, and Tabitha (Tabby) Collins, 3, patients at the AFLAC Cancer Center and Blood Disorder Services at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, have some fun with a giant AFLAC duck. AFLAC and AFLAC sales associates have raised millions of dollars for the AFLAC Cancer Center to help in the fight against childhood cancer. In 2000, sales of approximately 18,000 stuffed toy ducks generated $180,000 for the center. 17 Strong Product Line Makes Building a Larger Distribution System for Complete Coverage For us to further tap into the U.S. market, it is In 2000, AFLAC U.S. extended its position as the crucial that we continue to expand our sales force. -

Personal Accident Indemnity Plan Accident-Only Insurance

Level 2 Personal Accident Indemnity Plan Accident-Only Insurance Plan Benefits • Emergency Treatment • Follow-Up Treatment • Initial Hospitalization • Hospital Confinement • Physical Therapy • Accidental-Death • Wellness • Plus ... much more Form A34275BCA IC(9/05) Personal Accident Indemnity Plan Policy Series A-34000 Benefits are payable for a covered person’s death, Accident Specific-Sum Injuries Benefit dismemberment, or injury caused by a covered accident that Aflac will pay $35–$12,500 for: occurs on or off the job. Dislocations Burns Skin Grafts Accident Emergency Treatment Benefit Aflac will pay $120 for the insured and the spouse, and $70 for Eye Injuries Lacerations Fractures children if a covered person receives treatment for injuries Broken Teeth Comas Brain Concussions sustained in a covered accident. This benefit is payable for X-rays, treatment by a physician, or treatment received in a Paralysis Surgical Procedures hospital emergency room. Treatment must be received within 72 hours of the accident for benefits to be payable. This Treatment must be performed on a covered person for injuries benefit is payable once per 24-hour period and only once per sustained in a covered accident. We will pay for no more than covered accident, per covered person. two dislocations per covered accident, per covered person. Dislocations must be diagnosed within 72 hours of the covered accident. Benefits are payable for only the first Accident Follow-Up Treatment Benefit dislocation of a joint. If a physician reduces a dislocation with Aflac will pay $35 for one treatment per day for up to a local or no anesthesia, we will pay 25% of the amount shown maximum of six treatments per covered accident, per covered for the closed reduction dislocation. -

Benefits and Business at Aflac and L.L. Bean

TOtal REWarDS INSTRUCTOR’S MANUAL Benefits and Business at Aflac and L.L. Bean By Sandra M. Reed, SPHR PROJECT TEAM Author: Sandra M. Reed, SPHR SHRM project contributors: Bill Schaefer, SPHR Nancy A. Woolever, SPHR External contributor: Sharon H. Leonard Copy editing: Katya Scanlan, copy editor Design: Kellyn Lombardi, graphic designer © 2009 Society for Human Resource Management. Sandra M. Reed, SPHR Note to HR faculty and instructors: SHRM cases and modules are intended for use in HR classrooms at universities. Teaching notes are included with each. While our current intent is to make the materials available without charge, we reserve the right to impose charges should we deem it necessary to support the program. However, currently, these resources are available free of charge to all. Please duplicate only the number of copies needed, one for each student in the class. For more information, please contact: SHRM Academic Initiatives 1800 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA 22314, USA Phone: (800) 283-7476 Fax: (703) 535-6432 Web: http://www.shrm.org/education/hreducation 09-0235-IM Case Overview In its 2008 annual Job Satisfaction Survey Report, the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) reported that for the past five years, employees rated compensation and benefits among the top three aspects most important to their job. But despite the importance of these aspects, employee satisfaction with their compensation and benefits packages remains low. According to a Conference Board report, “employees are least satisfied with their companies’ bonus plans, promotion policies, health plans and pensions”. Employers are missing critical opportunities to maximize employee job satisfaction and other organizational outcomes through their total rewards programs.1 In the book Dynamic Compensation for Changing organizations: People, Performance & Pay, The Hay Group asserts that traditional pay structures no longer keep pace with the emerging, strategy-focused organizations that exist in today’s globally competitive market. -

Prizm Premier

Claritas Consumer Profiles 2021 - Change List prizm Premier Variable Description Category Status SB000770PC Domestic light beer drank past 30 days Bud Light Lime (A) Alcohol NEW SB004988PC Malt alternatives drank past 30 days Other malt alternative (A) Alcohol NEW SB004989PC Malt alternatives drink most often Other malt alternative (A) Alcohol NEW SB004956PC Wine (types) bought past 3 months Other wine (A) Alcohol NEW SB004957PC Wine (types) drink most often Other wine (A) Alcohol NEW MM70300PC Buy Riders by Lee - 12 mo(A) Apparel and Jewelry NEW SB005203PC Model year of any vehicle (HHLD): 2010 (H) Automotive NEW SB005204PC Model year of any vehicle (HHLD): 2011 (H) Automotive NEW SB005213PC Model year of new vehicle (HHLD): 2008 or earlier (H) Automotive NEW SB005214PC Model year of new vehicle (HHLD): 2009 (H) Automotive NEW SB005223PC Model year of new vehicle (HHLD): 2018 (H) Automotive NEW SB005224PC Model year of new vehicle (HHLD): 2019 (H) Automotive NEW SB005233PC Model year of used vehicle (HHLD): 2016 (H) Automotive NEW SB005234PC Model year of used vehicle (HHLD): 2017 (H) Automotive NEW SB005243PC Number of new cars 2 New cars (H) Automotive NEW SB005244PC Number of new cars 3 New cars (H) Automotive NEW SB005253PC Number of vehicles 2 Vehicles (H) Automotive NEW SB005254PC Number of vehicles 3:Vehicles (H) Automotive NEW SB005263PC Number of used vehicles 2 Used vehicles (H) Automotive NEW SB005264PC Number of used vehicles 3 Used vehicles (H) Automotive NEW SB005273PC Make of any vehicle Chrysler (H) Automotive NEW SB005274PC -

C C Communications Claims Allowed by the Board of County Commissioners at Their Regular Meetings for the Months of July Thru September 2019

C C Communications Claims allowed by the Board of County Commissioners at their regular meetings for the months of July thru September 2019 Supplies & Services ADAMS CABLE EQUIPMENT INC 5,695.85 ADI 13,081.87 ADOBE MAX 2019 1,790.00 ADVANCED MEDIA TECHNOLO 1,786.69 AFLAC 4,869.81 AIR FILTER SALES & SERVICE 260.72 ALLISON, MACKENZIE,PAVLAKIS, WRIGHT 1,848.08 ALLSTREAM 157.29 AMAZON CAPITAL SERVICES- NET 30 11,256.04 AMERICAN CAR WASH 10.00 AMERICAN DOCUMENT DESTRUCTION 129.00 AMERIGAS 536.00 ANAYA, KRISTI 140.00 ANIXTER, INC 51.24 ANPI, LLC - NS 16,316.84 APPLE COMPUTER, INC. 2,098.00 ARIN 2,000.00 AT&T 3,224.32 AUDIO ON HOLD LTD 212.00 BALLARD, DAWN 64.98 BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY 1,000.00 BROADCASTERS GENERAL STORE INC 4,092.00 BROWN, PATRICIA 435.00 BSG TPV, LLC 302.10 C BAR R 1,107.02 CABLE TECHNOLOGIES INTERNATIONAL, INC 441.50 CALIX INC 314,721.12 CAMILON, MELESSA 2,237.00 CBS SPORTS NETWORK 1,886.92 CC COMMUNICATIONS 8.10 CCHS CHEER 110.00 CDW GOVERNMENT, INC 2,279.09 CEDA BUSINESS COUNCIL 430.00 CHRISTENSEN AUTOMOTIVE OF FALLON 418.08 CHURCHILL AREA REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION 2,500.00 CHURCHILL ARTS COUNCIL 1,800.00 CHURCHILL COUNTY CLERK/TRES. 624,999.99 CHURCHILL COUNTY COMPTROLLER 8,655.41 CHURCHILL COUNTY COMPTROLLER FUEL 11,523.47 CHURCHILL COUNTY FEDERAL CREDIT UNION 121,587.14 CHURCHILL COUNTY PLANNING DEPARTMENT 11,514.87 CHURCHILL COUNTY SOCIAL SERVICES 100.00 CHURCHILL COUNTY TREASURER 4,563.51 CIGNA HEALTH & LIFE INSURANCE 126,075.79 CIGNA-LINA 6,500.37 CITY OF FALLON/ CITY CLERK 15,446.25 CLEARFIELD, INC 14,371.55 COALITION FOR WILLIAM N PENNINGTON LIFE 2,500.00 CODALE ELECTRIC SUPPLY, INC 12,485.57 COGENT COMMUNICATIONS INC 6,075.00 COMCAST SPORTSNET BAY AREA 20,492.64 COMMSOFT 13,918.50 COMMUNICATIONS WORKERS OF AMERICA 1,351.38 COMSTOCK TELECOM 16,364.96 CONNECTWISE, INC. -

2020 Financial Analysts Briefing

2020 Financial Analysts Briefing About This Book This book primarily contains slides and excerpts from Aflac Incorporated’s 2020 Financial Analysts Briefing held on November 19, 2020 at Aflac’s Paul S. Amos Building in Columbus, Ga., along with additional information. All information is intended to provide a comprehensive discussion and analysis of Aflac Incorporated’s operations. The information contained in this book was based on conditions that existed at the end of the third quarter of 2020. Circumstances may have changed materially since these presentations were made. The company undertakes no obligation to update the presentations. This information was prepared as a supplement to the company’s annual and quarterly releases, 10-Ks and 10-Qs. This book does not include footnotes to the financial statements or certain items that appear in reports or registration statements filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. We believe the information presented in this book was accurate at the time of the presentations, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. A webcast of this event’s presentations is available for one year following the event at investors.aflac.com. Forward-Looking Information The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 provides a “safe harbor” to encourage companies to provide prospective information, so long as those informational statements are identified as forward-looking and are accompanied by meaningful cautionary statements identifying important factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from those included in the forward-looking statements. The company desires to take advantage of these provisions. This document contains cautionary statements identifying important factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from those projected herein, and in any other statements made by company officials in communications with the financial community and contained in documents filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). -

C C Communications Claims Allowed by the Board of County Commissioners at Their Regular Meetings for the Months of October Thru December 2019

C C Communications Claims allowed by the Board of County Commissioners at their regular meetings for the months of October thru December 2019 Supplies & Services ADAMS CABLE EQUIPMENT INC 16,391.05 ADI 20,399.34 ADVANCED MEDIA TECHNOLO 1,663.34 AFLAC 4,869.81 ALLSTREAM 101.01 ALTEC 118.17 ALTEC AIR, LLC 563.50 AMAZON CAPITAL SERVICES- NET 30 6,967.41 AMERICAN CAR WASH 15.00 AMERICAN DOCUMENT DESTRUCTION 159.00 AMERIGAS 671.52 ANAYA, KRISTI 40.00 ANIXTER, INC 974.70 ANPI, LLC - NS 14,344.86 AT&T 477.00 AUDIO ON HOLD LTD 177.00 BATAVIA SERVICES 2,029.99 BATTLEBORN FIRE EXTINGUISHER SERVICE 1,330.00 BELL, STEVEN N. 1,100.00 BROWN, PATRICIA 202.50 BSG TPV, LLC 300.00 BUREAU OF RECLAMATION 4,798.10 CALIX INC 227,902.41 CAMILON, MELESSA 364.14 CAPS 280.00 CAROUSEL INDUSTRIES OF N.A. INC 22,219.20 CBS SPORTS NETWORK 1,850.58 CC SEARCH & RESCUE ASSOC. 200.00 CCHS BOYS BASKETBALL 300.00 CCHS GIRLS BASKETBALL 550.00 CEDA BUSINESS COUNCIL 45.00 CHRISTENSEN AUTOMOTIVE OF FALLON 347.00 CHURCHILL COUNTY CLERK/TRES. 325,024.99 CHURCHILL COUNTY COMPTROLLER 7,604.97 CHURCHILL COUNTY COMPTROLLER FUEL 9,441.56 CHURCHILL COUNTY FEDERAL CREDIT UNION 142,113.13 CHURCHILL COUNTY MUSEUM 480.00 CHURCHILL COUNTY PLANNING DEPARTMENT 11,043.76 CHURCHILL COUNTY SHERIFF'S DEPT 152.00 CHURCHILL COUNTY TREASURER 4,375.25 CIGNA HEALTH & LIFE INSURANCE 132,112.06 CIGNA-LINA 6,691.02 CITY OF RENO 594.13 CITY OF YERINGTON 15.00 CLARK CO ASSESSOR 387.58 CLEARFIELD, INC 13,470.08 COGENT COMMUNICATIONS INC 6,075.00 COMCAST SPORTSNET BAY AREA 20,160.00 COMMSOFT 95,761.23 COMMUNICATIONS WORKERS OF AMERICA 1,351.38 COMSTOCK TELECOM 21,174.74 COMTEK CENTER 2,956.00 CONNECTWISE, INC. -

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Form

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2014 or TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-07434 Aflac Incorporated (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Georgia 58-1167100 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 1932 Wynnton Road, Columbus, Georgia 31999 (Address of principal executive offices) (ZIP Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: 706.323.3431 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $.10 Par Value New York Stock Exchange Tokyo Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

2Q 16 Earnings Call Transcript

GRAY TELEVISION, INC. Moderator: Hilton Howell, Jim Ryan, Kevin Latek 08-04-16/10:00 am CT Confirmation # 3173477 Page 1 GRAY TELEVISION, INC. Moderator: Hilton Howell, Jim Ryan, Kevin Latek August 4, 2016 10:00 am CT Operator: Good day, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the Gray Television’s Second Quarter 2016 Earnings Call. Today’s conference is being recorded. At this time, I would like to turn the conference over to Hilton Howell, Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer. Please go ahead, sir. Hilton Howell: Thank you, operator. Good morning. I am Hilton Howell, the Chairman and CEO of Gray Television. I want to thank all of you for joining our second quarter 2016 earnings call. I am joined today by our Chief Financial Officer, Jim Ryan, and our Chief Legal and Development Officer, Kevin Latek. Before we get started, I want to take a point of personal congratulations to officially welcome, Luis Garcia, who joined our Board of Directors at the end of June. Luis is President and the Lead Strategist at San Antonio based MarketVision, which is a marketing firm focused on diverse audiences and cultural relevant communications from clients ranging from Fortune 500 companies to leading non-profit institutions. GRAY TELEVISION, INC. Moderator: Hilton Howell, Jim Ryan, Kevin Latek 08-04-16/10:00 am CT Confirmation # 3173477 Page 2 We are very gratified by his decision to join our board and we will benefit greatly from his considerable experience as an entrepreneur, a marketer and a leader in the dynamic media world in which Gray operates.