Czech Republic by Lubomír Kopeček

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Radio Network

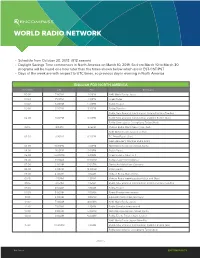

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

Twenty Years After the Iron Curtain: the Czech Republic in Transition Zdeněk Janík March 25, 2010

Twenty Years after the Iron Curtain: The Czech Republic in Transition Zdeněk Janík March 25, 2010 Assistant Professor at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic n November of last year, the Czech Republic commemorated the fall of the communist regime in I Czechoslovakia, which occurred twenty years prior.1 The twentieth anniversary invites thoughts, many times troubling, on how far the Czechs have advanced on their path from a totalitarian regime to a pluralistic democracy. This lecture summarizes and evaluates the process of democratization of the Czech Republic’s political institutions, its transition from a centrally planned economy to a free market economy, and the transformation of its civil society. Although the political and economic transitions have been largely accomplished, democratization of Czech civil society is a road yet to be successfully traveled. This lecture primarily focuses on why this transformation from a closed to a truly open and autonomous civil society unburdened with the communist past has failed, been incomplete, or faced numerous roadblocks. HISTORY The Czech Republic was formerly the Czechoslovak Republic. It was established in 1918 thanks to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and his strong advocacy for the self-determination of new nations coming out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after the World War I. Although Czechoslovakia was based on the concept of Czech nationhood, the new nation-state of fifteen-million people was actually multi- ethnic, consisting of people from the Czech lands (Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia), Slovakia, Subcarpathian Ruthenia (today’s Ukraine), and approximately three million ethnic Germans. Since especially the Sudeten Germans did not join Czechoslovakia by means of self-determination, the nation- state endorsed the policy of cultural pluralism, granting recognition to the various ethnicities present on its soil. -

Krizový Management ODS Od Roku 2013 Po Současnost

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sociálních studií Katedra politologie Krizový management ODS od roku 2013 po současnost Diplomová práce Bc. Nikola Pechtorová Vedoucí práce: Obor: Politologie Mgr. Otto Eibl, Ph.D. UČO: 385739 Brno 2017 Chtěla bych tímto poděkovat vedoucímu své práce Mgr. Otto Eiblovi, Ph.D. za jeho ochotu, cenné rady, komentáře a přátelský přístup po celou dobu tvorby této diplomové práce. Dále bych ráda poděkovala své rodině a příteli za pomoc a podporu, které se mi po celou dobu studia, i teď v jeho závěru, dostávaly. Prohlášení o autorství práce Prohlašuji, že jsem svou diplomovou práci na téma Krizový management ODS od roku 2013 po současnost vypracovala samostatně a za použití zdrojů uvede- ných v seznamu literatury. V Brně dne 28. května 2017 ................................................................ Abstract Pechtorová, N. Crisis management of ODS from 2013 to the present. Master thesis. Brno, 2017. The thesis studies causes of the ODS crise, which was associated with the events of the year 2013, the mechanisms and methods of solution used by ODS during the crise. The theoretical part is devoted to concepts, which dealing with crises ma- nagement, crisis communication, reputation and damaged image of the party. The research part is devoted to the analysis of the causes of ODS crisis, based on the construction of the image of the crisis, which was built on the basis of contempo- rary media, social networks and available documents. Subsequently, I analyze how the ODS used the solution to the crisis. There are used interviews with Miroslava Němcová and Petr Fiala. The aim of the thesis is to identify the causes of the crisis and analyze its solution. -

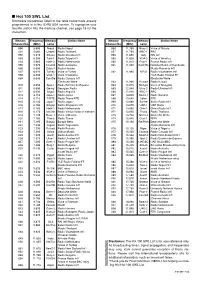

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

The Czech Foreign Policy in the Asia Pacific

CHAPTER 11 Chapter 11 The Czech Foreign Policy in the Asia Pacific IMPROVING BALANCE, MOSTLY UNFULFILLED POTENTIAL Rudolf Fürst, Alica Kizeková, David Kožíšek Executive Summary: The Czech relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC, hereinafter referred to as China) have again generated more interest than ties with other Asian nations in the Asia Pacific in 2017. A disagreement on the Czech-China agenda dominated the political and media debate, while more so- phisticated discussions about the engagement with China were still missing. In contrast, the bilateral relations with the Republic of Korea (ROK) and Japan did not represent a polarising topic in the Czech public discourse and thus remained largely unpoliticised due to the lack of interest and indifference of the public re- garding these relations. Otherwise, the Czech policies with other Asian states in selected regions revealed balanced attitudes with both proactive and reactive agendas in negotiating free trade agreements, or further promoting good relations and co-operation in trade, culture, health, environment, science, academia, tour- ism, human rights and/or defence. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL CONTEXT In 2017, the Czech foreign policy towards the Asia Pacific1 derived from the Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Czech Republic,2 which referred to the region as signifi- cant due to the economic opportunities it offered. It also stated that it was one of the key regions of the world due to its increased economic, political and security-related importance. Apart from the listed priority countries – China, Japan, and South Korea, as well as India – the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the re- gion of Central Asia are also mentioned as noteworthy in this government document. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Czech-Israeli Intergovernmental Consultations Joint Statement Prague, May 17, 2012 Today, May 17, 2012, the Government of the C

Czech-Israeli Intergovernmental Consultations Joint Statement Prague, May 17, 2012 Today, May 17, 2012, the Government of the Czech Republic and the Israeli Government are holding their intergovernmental consultations in Prague. The Prime Minister of the Czech Republic, Mr. Petr Ne čas, and the Prime Minister of the State of Israel, Mr. Benjamin Netanyahu, note with satisfaction the friendship and the historical partnership between the two countries, the unrelenting reciprocal support, the mutual respect for each other's sovereign status and the joint recognition in the political, defense and economic requirements of the two countries. The Prime Ministers emphasize their aspiration to further strengthen the close relations between the two Governments and the unique ties between the two peoples, based on a thousand-year-old affinity between the Czech people and the Jewish people. The Prime Ministers wish to thank all those who work tirelessly to advance the ties between the two countries. The following are the Government members participating in the consultations: On the Czech Republic side: Prime Minister Petr Ne čas First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs , Karel Schwarzenberg Minister of Industry and Trade, Martin Kuba Minister of Education, Youth and Sports, Petr Fiala Minister of Labor and Social Affairs, Jaromír Drábek Minister of Transport, Pavel Dobeš Minister for Regional Development, Kamil Jankovský Minister of Culture, Alena Hanáková On the Israeli side: Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu Deputy Prime Minister -

The Monkey Cage "Democracy Is the Art of Running the Circus from the Monkey Cage." -- H.L

11/5/13 The Czech paradox: Did the winner lose and the losers win? Sign In SUBSCRIBE: Home Delivery Digital Real Estate Rentals Cars Today's Paper Going Out Guide Find&Save Service Alley PostT V Politics Opinions Local Sports National World Business Tech Lifestyle Entertainment Jobs More The Monkey Cage "Democracy is the art of running the circus from the monkey cage." -- H.L. Mencken What's The Monkey Cage? Archives Follow : The Monkey Cage The Czech paradox: Did the winner lose and the losers win? BY TIM HAUGHTON, TEREZA NOVOTNA AND KEVIN DEEGAN-KRAUSE October 30 at 5:45 am More 3 Comments Also on The Monkey Cage Is the nonproliferation agenda stuck in the Cold War? Make-up artists prepare the Czech Social Democrat (CSSD) chairman Bohuslav Sobotka for his TV appearance after early parliamentary elections finished, in Prague, on Saturday, Oct. 26, 2013. (CTK, Michal Kamaryt/ Associated Press) [Joshua Tucker: Continuing our series of Election Reports, we are pleased to welcome the following post-election report on the Oct. 25-26 Czech parliamentary elections from political scientists Tim Haughton (University of Birmingham, UK), Tereza Novotna (Universite Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium) and Kevin Deegan-Krause, (Wayne State University), who blogs about East European politics at the excellent Pozorblog. Deegan-Krause's pre-election report is available here.] ***** Czech party politics used to be boring. The 2013 parliamentary election, however, highlights the transformation of the party system, the arrival of new entrants and the woes faced by the long-established parties. The Czech Social Democratic Party (CSSD) won the election, but the margin of victory was slender. -

PDF Download

15 November 2019 ISSN: 2560-1628 2019 No. 9 WORKING PAPER Development of Czech-Chinese diplomatic and economic relationships after 1949 Ing. Renata Čuhlová, Ph.D, BA (Hons) Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 [email protected] china-cee.eu Development of Czech-Chinese diplomatic and economic relationships after 1949 Abstract The cooperation between Czechia and PRC went through an extensive development, often in the context of contemporary political changes. The paper analyses the impact of bilateral diplomacy on the intensity of trade and investment exchange and it investigates the mutual attractiveness of the markets. Based on this analysis, the third part focuses on the existing problems, especially trade deficit, and it highlights the potential fields for further strengthening of partnership. The methodology framework is based on empirical approach and it presents a comprehensive case study mapping the evolution of Czech-Chinese dialogue in terms of diplomacy, economic exchange and existence of supporting organizations. Keywords: Czech-Chinese relationships, bilateral investment, diplomacy, economic and trade cooperation Introduction Despite of the transcontinental geographic distance and intercultural differences including languages barrier, Czechia, a Central European country, formerly known as Czechoslovakia until 1993, and People´s Republic of China (PRC) have experienced a great deal of discontinuity during last decades starting from big expectations in 1950s based on past time investment trade tradition during 1920s-1930s through very cold estrangement till the current strong partnership. The approach of the Czechia towards PRC has rapidly evolved and changed through the history, mainly due to contemporary political forces. -

Petr Nečas Zum Premierminister Ernannt

LÄNDERBERICHT Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. TSCHECHIEN DR. HUBERT GEHRING TOMISLAV DELINIC Mitte-Rechts-Koalition steht - MAREN HACHMEISTER Petr Nečas zum Premierminister 30. Juni 2010 ernannt www.kas.de MITTE-RECHTS-PARTEIEN EINIGEN SICH www.kas.de/tschechien Vorbereitung des Staatshaushaltes be- nächsten Jahr auf Steuermehreinnahmen schleunigt Verhandlungen von weiteren 30 Mrd. CZK (1,2 Mrd. €). Die Europäische Kommission bezeichnet Die Koalitionsverhandlungen der drei Mit- die tschechischen Sparmaßnahmen der te-Rechts-Parteien ODS, TOP 09 und VV Regierung Fischer unterdessen schon als wurden nach den tschechischen Parla- „ausreichend“, um die Haushaltsziele mentswahlen Ende Mai mit Hochdruck 2010 zu erreichen. Die Neuverschuldung vorangetrieben. Staatspräsident Václav wird voraussichtlich mit 5,7% des BIP Klaus ernannte Petr Nečas am 28. Juni noch über den 3% der EU- zum Premierminister. Am 29 Juni wurde Konvergenzkriterien liegen. schließlich auch die Regierung zusam- mengestellt. Dem Premierminister und Zunächst überschattete die Wahl des Par- ODS-Vorsitzenden Nečas gelang es so- lamentsvorsitzenden die neue Dreieinig- mit, die Koalitionsverhandlungen noch keit der Mitte-Rechts-Koalition – dem vor Beginn der Haushaltsverhandlungen Gewohnheitsrecht folgend beanspruchte am 07. Juli erfolgreich zu einem Ende zu nämlich die nach den Wahlen stimmen- bringen. stärkste Partei, die Sozialdemokraten (ČSSD), diesen Posten für sich. Sie konn- Koalitionsvereinbarung mit härtestem ten mit ihrem Kandidaten Lubomír Zaorá- Sparpaket der tschechischen Geschich- lek schließlich nur den stellvertretenden te Parlamentsvorsitz ergattern, da die künf- tige Koalition Miroslava Němcová (ODS) Die Koalitionsvereinbarung der Mitte- durchsetzte. Rechts-Koalition enthält sieben Kapitel. Nach den anfänglichen Forderungen der Auch die Frage der Ministerienverteilung Partei VV zur Kürzung des Verteidigungs- brachte harte Verhandlungen mit sich. -

Lutherlenin Vysílání Eine Sendung a Broadcasting

Studio 1 Studio 2 Studio 3 #LutherLenin 12:00-13:30 Miroslav Petříček: Confrontage, 500 years Radio Corax and Rádio Papular Prague: Vysílání of modernity (45 min, Czech, English Radio Revolts 1 - Meeting of Czech translation) and German radio activists for the foundation Eine Sendung of a Free Radio Prague Milena Bartlová: How to Share a Revolution? – (90 min, English, Czech translation) A Broadcasting Communication between the educated and the illiterate during Hussitism (45 min, Czech, English translation) 13:40-15:10 A2 collective: What is left of the revolution? Berliner Gazette: Friendly Fire - Reports from Miloš Horanský: Commentary to the Manifesto (90 min, Czech, English translation) the Frontlines of Democracy (3 parts) “The Party of Moderate Progress Within the Part 1: Krystian Woznicki, moderated by Bounds of the Law““ on the last election Sabrina Apitz: What is to be done?, or: Update (90 min, Czech) on the Coming Insurrection (45 min, English, Czech translation) 15:20-16:50 Alexander Tschernek and Tomáš Sedláček: Berliner Gazette: Friendly Fire: Reports from the Natálie Pleváková: Audio broadcasts - Anarchy & Freedom - A Walk Into The Woods Frontlines of Democracy (3 parts) how radio has changed music (90 min, English and German, Czech Part 2: Sazae Bot, moderated by Michael (90 min, Czech) translation) Prinzinger: Anonymous Blockbuster, or: Welcome to the Spectres of a Bot (45 min, English, Czech translation) Part 3: Iskra Geshoska, moderated by Magdalena 2/12/2017 Taube: How to Hijack a Country, or: Do we still Studio Hrdinů Live in the Age of Revolutions? (45 min, English, Prague Czech translation) lenin 500 years of revolution, reformation, media and subject CreWcollective: Delay Observer`s Office CreWcollective: Delay Observer`s Office (directed by: Jan Horák and Roman Štětina) (directed by: Jan Horák and Roman Štětina) 3 scenes, 3 radio stations, 36 hours of programme 17:15-18:45 Ilona Švihlíková and Miroslav Tejkl, moderated Andreas Bernard, moderated by Alexander Stefan Höhne: From Signal to Noise. -

On the Emergence of Political Identity in the Czech Mass

www.ssoar.info On the Emergence of Political Identity in the Czech Mass Media: The Case of the Democratic Party of Sudetenland Leudar, Ivan; Nekvapil, Jiri Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Leudar, I., & Nekvapil, J. (1998). On the Emergence of Political Identity in the Czech Mass Media: The Case of the Democratic Party of Sudetenland. Sociologický časopis / Czech Sociological Review, 6(1), 43-58. https://nbn- resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-54259 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use.