74224648.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Future for Local and Regional Media

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Future for local and regional media Fourth Report of Session 2009–10 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 24 March 2010 HC 43-II (Incorporating HC 699-i-iv of Session 2008-09) Published on 6 April 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon and East Chelmsford) (Chair) Mr Peter Ainsworth MP (Conservative, East Surrey) Janet Anderson MP (Labour, Rossendale and Darwen) Mr Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr Mike Hall MP (Labour, Weaver Vale) Alan Keen MP (Labour, Feltham and Heston) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East) Adam Price MP (Plaid Cymru, Carmarthen East and Dinefwr) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) The following members were also members of the committee during the inquiry: Mr Nigel Evans MP (Conservative, Ribble Valley) Helen Southworth MP (Labour, Warrington South) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

MGEITF Prog Cover V2

Contents Welcome 02 Sponsors 04 Festival Information 09 Festival Extras 10 Free Clinics 11 Social Events 12 Channel of the Year Awards 13 Orientation Guide 14 Festival Venues 15 Friday Sessions 16 Schedule at a Glance 24 Saturday Sessions 26 Sunday Sessions 36 Fast Track and The Network 42 Executive Committee 44 Advisory Committee 45 Festival Team 46 Welcome to Edinburgh 2009 Tim Hincks is Executive Chair of the MediaGuardian Elaine Bedell is Advisory Chair of the 2009 Our opening session will be a celebration – Edinburgh International Television Festival and MediaGuardian Edinburgh International Television or perhaps, more simply, a hoot. Ant & Dec will Chief Executive of Endemol UK. He heads the Festival and Director of Entertainment and host a special edition of TV’s Got Talent, as those Festival’s Executive Committee that meets five Comedy at ITV. She, along with the Advisory who work mostly behind the scenes in television times a year and is responsible for appointing the Committee, is directly responsible for this year’s demonstrate whether they actually have got Advisory Chair of each Festival and for overall line-up of more than 50 sessions. any talent. governance of the event. When I was asked to take on the Advisory Chair One of the most contentious debates is likely Three ingredients make up a great Edinburgh role last year, the world looked a different place – to follow on Friday, about pay in television. Senior TV Festival: a stellar MacTaggart Lecture, high the sun was shining, the banks were intact, and no executives will defend their pay packages and ‘James Murdoch’s profile and influential speakers, and thought- one had really heard of Robert Peston. -

Broadcasting Committee

Broadcasting Committee Alun Davies Chair Mid and West Wales Peter Black Paul Davies South Wales West Preseli Pembrokeshire Nerys Evans Mid and West Wales Contents Section Page Number Chair’s Foreword 1 Executive Summary 2 1 Introduction 3 2 Legislative Framework 4 3 Background 9 4 Key Issues 48 5 Recommendations 69 Annex 1 Schedule of Witnesses 74 Annex 2 Schedule of Committee Papers 77 Annex 3 Respondents to the Call for Written Evidence 78 Annex 4 Glossary 79 Chair’s Foreword The Committee was established in March 2008 and asked to report before the end of the summer term. I am very pleased with what we have achieved in the short time allowed. We have received evidence from all the key players in public service broadcasting in Wales and the United Kingdom. We have engaged in lively debate with senior executives from the world of television and radio. We have also held very constructive discussions with members of the Welsh Affairs Committee and the Scottish Broadcasting Commission. Broadcasting has a place in the Welsh political psyche that goes far beyond its relative importance. The place of the Welsh language and the role of the broadcast media in fostering and defining a sense of national identity in a country that lacks a national press and whose geography mitigates against easy communications leads to a political salience that is wholly different from any other part of the United Kingdom. Over the past five years, there has been a revolution in the way that we access broadcast media. The growth of digital television and the deeper penetration of broadband internet, together with developing mobile phone technology, has increased viewing and listening opportunities dramatically; not only in the range of content available but also in the choices of where, when and how we want to watch or listen. -

Open PDF 113KB

Select Committee on Communications and Digital Corrected oral evidence: The future of journalism Tuesday 21 July 2020 3 pm Watch the meeting Members present: Lord Gilbert of Panteg (The Chair); Lord Allen of Kensington; Baroness Bull; Baroness Buscombe; Viscount Colville of Culross; Baroness Grender; Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall; Baroness Meyer; Baroness Quin; Lord Storey; The Lord Bishop of Worcester. Evidence Session No. 22 Virtual Proceeding Questions 187 - 197 Witness I: Michael Jermey, Director of News and Current Affairs at ITV. USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT This is a corrected transcript of evidence taken. 1 Examination of witness Michael Jermey. Q187 The Chair: I welcome our witness, Michael Jermey, ITV’s director of news and current affairs. Last week we heard from BBC News and Channel 4 News. Michael Jermey, as director of news and current affairs, is responsible primarily for ITV’s regional output, which ITV produces itself, and has overall directorial responsibility for news at ITV. Michael, welcome. Thank you for coming and giving us evidence. There are a few areas that we want to talk to you about. You will have seen some of the evidence that we have already received, and thank you for the evidence that you have produced for us. Could you please start by giving us a brief introduction to yourself and to ITV News and exactly what you are responsible for in the organisation? Then we will talk to you about the impact of Covid on ITV. The session is being broadcast online, and a transcript will be taken. Michael Jermey: Thank you for inviting me to give evidence to your inquiry, which is an important one. -

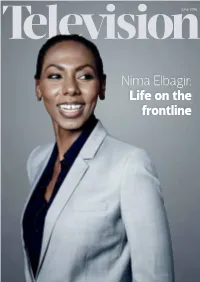

Nima Elbagir: Life on the Frontline Size Matters a Provocative Look at Short-Form Content

June 2016 Nima Elbagir: Life on the frontline Size matters A provocative look at short-form content Pat Younge CEO, Sugar Films (Chair) Randel Bryan Director of Content and Strategy UK, Endemol Shine Beyond UK Adam Gee Commissioning Editor, Multi-platform and Online Video (Factual), Channel 4 Max Gogarty Daily Content Editor, BBC Three Kelly Sweeney Director of Production/Studios, Maker Studios International Andy Taylor CEO, Little Dot Studios Steve Wheen CEO, The Distillery 4 July The Hospital Club, 24 Endell Street, London WC2H 9HQ Booking: www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society June 2016 l Volume 53/6 From the CEO The third annual RTS/ surroundings of the Oran Mor audito- Mockridge, CEO of Virgin Media; Cathy IET Joint Public Lec- rium in Glasgow. Congratulations to Newman, Presenter of Channel 4 News; ture, held in the all the winners. and Sharon White, CEO of Ofcom. unmatched surround- Back in London, RTS Futures held Steve Burke, CEO of NBCUniversal, ings of London’s Brit- an intimate workshop in the board- will deliver the opening keynote. ish Museum, was a room here at Dorset Rise: 14 industry An early-bird rate is available for night to remember. I newbies were treated to tips on how those of you who book a place before was thrilled to see such a big turnout. to secure work in the TV sector. June 30 – just go to the RTS website: Nobel laureate Sir Paul Nurse gave a Bookings are now open for the RTS’s rts.org.uk/event/rts-london-conference-2016. -

Nuj.Pdf (PDF File, 65.6

Ofcom Consultation - Channel 3 and Channel 5: proposed programming obligations May 1, 2013 The National Union of Journalists is the voice for journalism and for journalists across the UK and Ireland working at home and abroad in all sectors of the media as freelances, casuals and staff in newspapers, news agencies, broadcasting, magazines, online, book publishing, in public relations and as photographers. The NUJ was founded in 1907 and has more than 30,000 members. The NUJ response will focus on question 2 of the consultation: Do you agree with ITV’s proposals for changes to its regional news arrangements in England, including an increase in the number of news regions in order to provide a more localised service, coupled with a reduction in overall news minutage? Brief responses to the other questions are at the end of the submission. 1. ITV is proposing that it almost halves its news output in the English Regions from just over four hours per week to two hours, 30 minutes. The quid pro quo for this is that they will reinstate their old regional production by creating 14 news regions/sub-regions. 2. This is against a backdrop of ITV increasing its pre-tax profits by 6 per cent in 2012, paying a full-year dividend and a special dividend – only the second year ITV has paid a dividend since the merger of Carlton and Granada in 2004. 3. ITV maintains that regional news is a considerable net cost to the business; however over the past decade ITV have reduced its spend on regional news by over a half (from £120 million to less that £60 million). -

Open PDF 300KB

Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee Oral evidence: The future of Public Service Broadcasting, HC 156 Tuesday 14 July 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 14 July 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Julian Knight (Chair); Kevin Brennan; Alex Davies-Jones; Clive Efford; Damian Green; Damian Hinds; John Nicolson; Giles Watling. Questions 106 - 217 Witnesses I: Dame Carolyn McCall, Chief Executive, ITV, and Magnus Brooke, Director of Policy and Regulatory Affairs, ITV. Examination of Witnesses Witnesses: Dame Carolyn McCall, Chief Executive, ITV, and Magnus Brooke, Director of Policy and Regulatory Affairs, ITV. Q106 Chair: This is the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee and this is a hearing into the future of public service broadcasting and also we will be looking at the issue of Covid-19 and how that has affected our witnesses’ company today and public service broadcasting more generally. Before we begin, I am going to ask any of the members to indicate whether or not they have any interests in relation to this session. Giles Watling: Yes, I do, Chair. I am an occasional recipient of royalties from ITV. Chair: Thank you. Our witnesses today are Dame Carolyn McCall, the Chief Executive of ITV, and Magnus Brooke, the Director of Policy and Regulatory Affairs, ITV. Thank you for joining us today. Dame Carolyn, would you outline for the Committee the implications that Covid has had on your business and your public service broadcasting remit more broadly? Dame Carolyn McCall: Sure. Thank you very much for inviting us to do this. -

Breaking Into News Impact Report

BREAKING INTO NEWS IMPACT REPORT OCTOBER 2019 Breaking into News is an initiative run by Media Trust, in partnership with ITV News, to discover diverse new talent and identify top broadcast journalists of the future. The competition has been running since 2011. It offers aspiring journalists with limited journalism experience from across England, Wales and Northern Ireland training and mentoring from experienced journalists working in ten of ITV’s regional newsrooms. THE CONTEXT “JOURNALISM HAS SHIFTED TO “I WAS LIKE THE JUNIOR BUTLER A GREATER DEGREE OF SOCIAL TRYING TO BLAG A SEAT AT HIS EXCLUSIVITY THAN ANY OTHER LORDSHIP’S DINING TABLE IN PROFESSION” DOWNTON ABBEY” Milburn Report on Social Mobility, 2012 John Humphrys, former Today presenter 51% OF BRITAIN’S TOP 100 DISABLED PEOPLE ARE JOURNALISTS WENT TO PRIVATE NOTICABLY UNDER-REPRESENTED SCHOOL – MORE THAN SEVEN ACROSS THE SECTOR AND LESS TIMES THE UK AVERAGE REPRESENTED AT A SENIOR LEVEL The Sutton Trust, 2012 Diamond Report, 2018 SINCE BREAKING TYNE TEES & BORDER INTO NEWS ULSTER BEGAN IN 2011, YORKSHIRE GRANADA 71 FINALISTS CENTRAL WERE SELECTED WALES ANGLIA TO TAKE PART LONDON WEST & WEST COUNTRY ACROSS 10 ITV MERIDIAN NEWS REGIONS CLICK ON A PAST WINNER TO WATCH PAST WINNERS THEIR WINNING NEWS REPORT 2019 2018 2017 2016 TOBY WINSON HADEEL ELSHAK JOSH FARRELL SANA SARWAR MERIDIAN LONDON UTV LONDON 2015 2014 2012 2011 SALLY WYNTER NASAYBAH HUSSAIN MONIKA PLAHA SOPHIA KICHOU CENTRAL LONDON CENTRAL LONDON IN THE PREVIOUS TWO YEARS, 14 OUT OF 20 FINALISTS HAVE GONE ON TO WORK -

The History and Future of TV Election Debates in the UK

Ric Bailey's expert dissection of the first campaign debates among party leaders in REPORT the United Kingdom is a first-rate piece of analysis on an important, frequently misunderstood topic. Accessibly written and exhaustively researched, Squeezing Out the Oxygen- or Reviving Democracy? offers a unique, behind-the-scenes perspective on the 2010 Cameron-Clegg-Brown joint appearances, along with a broader consideration of the role of TV debates in British politics. This is a book that scholars of political communication will be citing for decades to come. Professor Alan Schroeder School of Journalism, Northeastern University, Boston Squeezing Out the Oxygen – or Reviving Author of Presidential Debates: 50 Years of High-Risk TV (Columbia University Press) Democracy? 2010 saw the first UK television debates between the party leaders. What was their e History and Future of TV Election Debates in the UK significance? Did they affect the result? What are the lessons for the future? In this finely written account, Ric Bailey, with the benefit of his BBC experience, offers an authoritative account which should be read not only by the politicians and the pundits but by all those seeking to make sense of democracy in Britain today. Professor Vernon Bogdanor CBE, FBA Ric Bailey Research Professor, Institute for Contemporary History, Kings College, London Author of The Coalition and the Constitution February 2012 Britain's Conservative Party leader Cameron, Liberal Democrat leader Clegg and PM Brown take part in the third and final televised party leaders' debate in Birmingham ©JEFF OVERS/BBC SELECTED RISJ PUBLICATIONS James Painter Poles Apart. The international reporting of climate scepticism Lara Fielden Regulating for Trust in Journalism. -

Global Multimodal News Frames on Climate Change

HIJXXX10.1177/1940161216661848The International Journal of Press/PoliticsWessler et al. 661848research-article2016 Article The International Journal of Press/Politics 2016, Vol. 21(4) 423 –445 Global Multimodal News © The Author(s) 2016 Reprints and permissions: Frames on Climate Change: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1940161216661848 A Comparison of Five ijpp.sagepub.com Democracies around the World Hartmut Wessler1, Antal Wozniak1, Lutz Hofer1, and Julia Lück1 Abstract This paper presents the first fully integrated analysis of multimodal news frames. A standardized content analysis of text and images in newspaper articles from Brazil, Germany, India, South Africa, and the United States covering the United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conferences 2010–2013 was conducted using a subset of photo-illustrated articles (n = 432) as well as the entire conference coverage (n = 1,311). In the photo-illustrated articles, four overarching multimodal frames were identified: global warming victims, civil society demands, political negotiations, and sustainable energy frames. The distribution of these global frames across the five countries is relatively similar, and a comparison of frames emerging from the national subsets also reveals a strong element of cross-national frame convergence. This is explained by the news production context at global staged political events, which features uniform media access rules and similar information supplies, as well as strong interaction between journalists from different countries and between journalists and other actors. Event-related frame convergence across vastly different contexts is interpreted as one mechanism by which truly transnational media debate can be facilitated that can potentially serve to legitimize global political decisions. In conclusion, perspectives for future qualitative and quantitative multimodal framing research are discussed. -

Shadow Cabinet Meetings with Proprietors, Editors and Senior Media Executives

Shadow Cabinet Meetings Tuesday 1st January 2013 – Sunday 30th June 2013 Shadow cabinet meetings with proprietors, editors and senior media executives. Ed Miliband MP 1 January 2013 – 30 June 2013 Leader of the Opposition’s meetings with proprietors, editors and senior media executives Date Name Location Purpose Nature of relationship* Gavin Allen London General discussion 17/1/2013 (Editor of Political News, BBC) Paul Waugh London Interview 30/1/2013 (Editor, PoliticsHome and Dods) Trinity Mirror London Town Hall style 24/4/2013 Town Hall meeting Debate 9/5/2013 Lobby drinks London Hosted reception reception for lobby journalists Paul McNamee London General discussion (Editor, The Big 19/6/2013 Issue) and Lara McCullagh (Marketing and Communications Director, The Big issue) 20/6/2013 New Statesman London Attended reception Summer Reception 20/6/2013 Financial Times London Attended reception Summer Reception 26/6/2013 ITV Summer London Attended reception Reception 27/6/13 Speech to London Speech Women in Advertising and Communications 27/6/13 Ian Katz (Deputy London General Discussion Editor, The Guardian) John Witherow London General discussion 28/6/2013 (Editor, The Times) 28/6/2013 Evgeny Lebedev London Reception (Chairman, Independent Print Ltd and Evening Standard Ltd) Other interaction between Leader of the Opposition and proprietors, editors and senior media executives Name Medium Frequency and density Nature of relationship* Evgeny Lebedev Phone calls and text Phone call on 26/2/2013 and (Chairman, messages occasional text messages -

Black History Month on Itv

BLACK HISTORY MONTH ON ITV ITV will mark Black History Month with specially commissioned new shows and channel branding throughout October. ITV will celebrate the contribution of black people to television, comedy, history and our wider culture in new programmes and the work of black artists will feature as the channel’s on air branding in a series of idents that will appear throughout the month. The new programmes include: IRL with Team Charlene - TX 3 October on ITV and CITV IRL with Team Charlene is a new show that aims to break down and explain major issues for children. In this special, ITV News Presenter Charlene White is joined by her team of celebrity friends, experts and young people from across the UK. They'll talk about everything from what racism is and the Black Lives Matter movement to why we have different skin colours. Through a mix of animation, musical performances and personal stories the team takes an engaging and accessible approach to serious events. The programme will transmit simultaneously on CITV and ITV. Charlene White is the co-producer with Jessica Symons as Executive Producer for ITN Productions. IRL with Team Charlene is commissioned for ITV by Paul Mortimer, Head of Digital Channels and Acquisitions, Michael Jermey, Director of News and Current Affairs and Gemma John-Lewis, Assistant Commissioner, Entertainment Alison Hammond: Back To School - TX 6 October at 9pm on ITV 1x60 Alison Hammond goes on the ultimate school history trip with a twist. In her own unique and inimitable style, Alison will be travelling the length and breadth of Britain to key historical sites - from Hadrian’s Wall to Hampton Court looking at the history we’re all taught in schools, but from a different angle.