The State of Academic Writing in Kenyan Universities: Making a Case for Kenyan Universities to Re-Conceptualize Their Approach to Teaching Academic Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

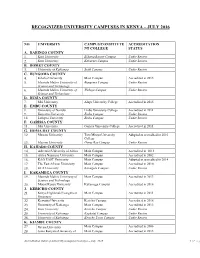

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

DANIEL OTIENO Qualification: Phd Department: Education

Academic Staff Profile 1.1 Personal Profile 1.1.1 Personal Details Name: DANIEL OTIENO Qualification: PhD Department: Educational Management, Policy and Curriculum Studies Designation/Position: Lecturer Email: [email protected] Contact Address: 43844-00200 Nairobi Area of Specialization: Educational Administration, Research Methods, Values- based Education, Leadership and Coaching Research Interests: Values Education, Organisational Development, Change management, Internationalisation, ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002- 3212-9058 Researcher ID: F-2940-2019 1.1.2 Academic & Professional Qualifications - PhD (Educational Administration) - M.Ed (Educational Administration) - B.Ed (Arts) 1.1.3 Employment History -10th September 2018 – Present: Lecturer, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya - 4th August 2017 – 10th September 2018: Tutorial Fellow, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya - 6th December 2011 – 3rd August 2017: Lecturer, Africa Nazarene University - 20th Sept 2010 – 6th December 2011: Part-time Lecturer, Africa Nazarene University, Kenya - January 1999 – 30th January 2009: Principal, Sathya Sai School - 1.1.4 Special Appointments - 1st February 2019 Appointed by the Dean to the School of Education International Annual Conference on Education and Lifelong Learning committee. Member of the planning committees for renewable five-year term. - 6th February 2019 to date Appointed to as External Examiner in the Department of Education – Africa Nazarene University. Examining Master of Education thesis. - 7th February 2019 Appointed to the Conference planning committee on career mentoring and leadership. - 20th August 2018 Appointed by Chair of Department as member of conference editorial committee of the 3rd International conference on Education Planning Committee. Kenyatta University - 13th March 2018 Appointed by the Dean to the ISO Quality Team to Evaluate the implementation of Departmental Key Performance Indicators (KRI) - 1.2 Publications 1.2.1 Referred Journals Otieno, D. -

Lucy W. Ngige, Phd

LUCY W. NGIGE, PHD 1.0 PERSONAL INFORMATION Name: Lucy W. Ngige. Ph. D Designation: Senior Lecturer School Applied Human Sciences Department: Community Resource Management & Extension Specialization: Family and Child Ecology Address: Kenyatta University Postal Code: P.O. Box 43844 Nairobi 0100 Kenya Telephone [254]-020 8711622 ext.57140 (office) Fax: [254]-020 8711575 Cell-phone: [254]-0721548323, [254]-0734169731 E-Mail: [email protected] [email protected] 2.0 EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS 2.1 Academic Qualifications 1993: PHD (Family & Child Ecology), Michigan State University, East Lansing, USA. 1985: M.A. (Family & Child Ecology), Michigan State University, East Lansing, USA. 1981: B. Ed. (First Class Honors), University of Nairobi, Kenya. 2.2 Professional Courses 2014 Certificate of Completion of Teaching Methodology Course organized by Kenyatta University, Centre for Teaching Excellence and Evaluation. 2013 Certificate of Participation in the International Conference on Reconceptualizing Early Childhood Education awarded by RECE and Kenyatta University. 2012 Certificate of participation in the International Conference on Gender Based Violence awarded by Kenyatta University. 1 2008 Certificate of participation in the 12th International Biennial Conference on Adolescence awarded by the Society for Research in Adolescence, Chicago, USA. 2004 Certificate of participation in the 66th International Annual Conference of the National Council of Family Relations (NCFR) in Orlando, Florida, USA. 2003 Certificate in Good Corporate Governance for Senior University Managers awarded by Directorate of Personnel Management and Anti-Corruption Police Unit, Kenya. 2001 Certificate in Management Development for Women Managers in the Public Service awarded by Ford Foundation (USA) and Directorate of Personnel Management, Kenya. 1993 Proficiency courses in computer software packages at Lansing Community College, Michigan: USA. -

MKU Career Prospectus for High School Students

www.mku.ac.ke/ mountkenyauniversity MountKenyaUni MKU Career Prospectus Mount Kenya University for High School Students Developed in conjunction with January 2021 Edition VISION MISSION PHILOSOPHY To be a Global To provide world To harness Hub of Excellence class education, knowledge in in Education, research and applied Sciences Research innovation for global and Technology and Innovation. transformation for the service of and sustainable humanity development CORE VALUES The University’s core values that form the basis of engagement, teaching and learning are: • Innovation • Integrity • Academic freedom • Equity • Competitiveness ACADEMIC CHARACTER With an emphasis on science, technology and humanities, Mount Kenya University offers an all-rounded education including moral and professional education to all persons degree courses MKU graduates ready for the job market and wealth creation VISION MISSION PHILOSOPHY To be a Global To provide world To harness Contents Hub of Excellence class education, knowledge in Students Life: A Home from Home ........................................ 1 in Education, research and applied Sciences Research innovation for global and Technology Welcome by Chancellor............................................................ 2 and Innovation. transformation for the service of Word by Vice-Chancellor ......................................................... 3 and sustainable humanity development Experts rank MKU ................................................................. 5 Testimonials ........................................................................ -

N O Institution's Name Public University 1 Chuka University 2 Dedan Kimathi University of Technology 3 Egerton University 4 Ja

N Institution’s Name o Public University 1 Chuka University 2 Dedan Kimathi University of Technology 3 Egerton University 4 Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology 5 Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture & Technology (JKUAT) 6 Karatina University 7 Kenyatta University 8 Kisii University 9 Laikipia University 10 Masai Mara University 11 Maseno University 12 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology 13 Meru University of Science and Technology 14 Moi University 15 Multi Media University 16 Pwani University 17 South Eastern Kenya University 18 Technical Univeristy of Mombasa 19 Technical University of Kenya 20 University of Eldoret 21 University of Kabianga 22 University of Nairobi Private University 23 Adventist University of Africa 24 Africa International University 25 Africa Nazarene University 26 Aga Khan University 27 Catholic University Of Eastern Africa 28 Daystar University 29 East African University 30 Great Lakes University 31 International University of Professional Studies 32 International Leadership University 33 Kabarak University 34 KCA University 35 Kenya Methodist University 36 Mount Kenya University 37 Pan Africa Christian University 38 Pioneer International University 39 Scott Christian University 40 St Paul's University 41 Strathmore University 42 The Management University of Africa 43 The Presbyterian University of East Africa 44 Umma University 45 United States International University 46 University of Eastern Africa, Baraton University College 47 Co-operative University College 48 Embu -

Information Needs and Seeking Behaviour of Medical Teaching Staff of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Egerton University, Kenya

INFORMATION NEEDS AND SEEKING BEHAVIOUR OF MEDICAL TEACHING STAFF OF THE FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES, EGERTON UNIVERSITY, KENYA BY ANNE NAKHUMICHA TENYA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master in Information Science DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION SCIENCE FACULTY OF INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY KISII UNIVERSITY 2014 DECLARATION Declaration by the Candidate This is my original work and has not been presented for an award of a degree in any university known to me. Signature………………………………………Date………………………………… Anne Nakhumicha Tenya MIN 11/20007/11 Declaration by the Supervisors This thesis has been submitted for examination with our approval as the university supervisors. Signature……………………………………… Date………………………………… Dr. Elisha Ondieki Makori Lecturer, Department of Information Science Signature ……………………………………. Date………………………………… Mr. Festus Kipkorir Ng’etich Lecturer, Department of Information Science ii COPYRIGHT All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by means of mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without permission in writing from the author or Kisii University. iii DEDICATION This thesis is first dedicated to my late parents Mr. Jacob Tenya Musamali and mayi Rhodah Chuma Tenya who amidst of a challenging economic environment; laid a foundation for my education. The thesis is also dedicated to my sons: Austin Avudi and Titus Aradi, for understanding my reason for being away and exercised a lot of patience towards my absence. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Many people have contributed towards the production of this thesis. I am greatly indebted to them all. I wish to express my special gratitude to my supervisors: Dr. -

Research and Innovation Bulletin 2015

Mount Kenya University Directorate of Research and Development RESEARCH AND INNOVATION BULLETIN ISSUE No. 4: 2015 1 RESEARCH & INNOVATION BULLETIN | 2015 Directorate of Research and Development RESEARCH & INNOVATION BULLETIN Issue No. 4: 2015 Foreword Prof. Stanley Waudo, PhD Vice-Chancellor Mount Kenya University cience, technology and innovation (STI) are expected to play a pivotal role in Kenya’s Vision 2030 development blue print. Mount Kenya University is therefore committed to play its part in complementing Sgovernment efforts in socio-economic transformation of our society. Indeed, the University reckons that a knowledge-driven economy and not a resource-based one will be key in this endevour, largely informed by research and innovation. The University therefore continues to invest in research and innovation activities, and in the last fiscal year, we allocated Ksh. 50 million towards the same. The funds were invested towards equipping the Research Centre, establishing and running the Enterprise Academy, the first-ever in the region for youth empowerment geared towards job and wealth creation. The funds were also used for organizing a National Water Summit in Turkana county, funding research and innovation projects, supporting dissemination activities through facilitating faculty to publish in peer-refereed journals and to participate in both local and international conferences. The University has further organized capacity building workshops and community outreach activities. The University will continue supporting STI activities as an important catalyst towards socio- economic transformation of our society. Prof. Stanley Waudo, PhD Vice-Chancellor Mount Kenya University 1 RESEARCH & INNOVATION BULLETIN | 2015 Message from the Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Academic and Research Affairs Ms. -

Universities Act

LAWS OF KENYA UNIVERSITIES ACT No. 42 of 2012 Revised Edition 2013 [2012] Published by the National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General www.kenyalaw.org [Rev. 2013] No. 42 of 2012 Universities Universities NO. 42 OF 2012 UNIVERSITIES ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I – PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title. 2. Interpretation. 3. Objectives of University education. PART II – THE COMMISSION FOR UNIVERSITY EDUCATION 4. Establishment of the Commission. 5. Functions of the Commission. 6. Constitution of the Commission. 7. Qualification for appointment as member of Commission. 8. Vacancy of office. 9. Commission Secretary. 10. Deputy Secretary. 11. Qualification for appointment as Commission Secretary. 12. Other members of staff of the Commission. PART III – ESTABLISHMENT AND ACCREDITATION OF UNIVERSITIES 13. Establishment of a university. 14. Letter of Interim Authority. 15. Effect of letter of Interim Authority. 16. Duration of letter of Interim Authority. 17. Revocation of a Letter of Interim Authority. 18. Accreditation report for purposes of grant of Charter. 19. Grant or refusal to grant Charter. 20. Effect of a Charter. 21. Publication of Charter. 22. Variation, revocation of Charter. 23. Statutes. 24. Establishment of specialized degree awarding institutions. 25. Declaration of Technical Universities. 26. Universities in Counties. 27. Unauthorized use of a University name. 28. Accreditation of foreign universities. 29. Academic Freedom. PART IV – FINANCIAL PROVISIONS ON THE COMMISSION 30. Funds of the Commission. 31. Financial year. 32. Annual estimates. 33. Accounts and audit. U2A - 3 [Issue 2] No. 42 of 2012 [Rev. 2013] Universities Universities PART V – GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF UNIVERSITIES Section 34. -

The Effects of Rightsizing on Service Delivery: a Case Study of Egerton University

THE EFFECTS OF RIGHTSIZING ON SERVICE DELIVERY: A CASE STUDY OF EGERTON UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI EAST AFRICANA COUcCTIOM BY MAUREEN ANYANGO NGALA A research project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology (Labour-Management Relations) DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI University of NAIROBI Library Ilfllli 0479753 6 OCTOBER, 2003 DECLARATION Declaration by the Student This project is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University. No part of this thesis may be reproduced without the permission of the author and/or University of Nairobi, 3 d ^u o crv& t-a ANYANGO MAUREEN NGALA DATE ________ , EASl Af-KlCM*ACuLl.-C7i0i'i Declaration by the Supervisors This thesis has been submitted for examination with our approval as University supervisors. PROF. EDWARD MBURUGU DATE Associate Professor, Sociology Department University of Nairobi i t l s ^ — --------' T o f > o f 2 P ^ MR. BENEAH MUTSOTSO DATE Lecturer, Sociology Department University of Nairobi 1 DEDICATION This research project is dedicated to the following people: My husband: Frederick B. J. A. Ngala My Children: Ivan Aom Angaga Dina-Kimberly Mandera Agaga ^o' Alexander Abok Angaga 0 0 ** * Ayub Oketch Angaga *0 ^ **4 k A 05 My Parents: John R. Oyamo Margaret M. Oyamo For all the support, patience and encouragement you gave me throughout the time I was pursuing my M.A. degree. 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give thanks to my maker for giving me the wisdom and intellect that has been so vital in pursuing my studies and making me part of his great plan. -

Compiled From: Gradstate

Compiled from: GradState ..................................................... gradstate.com ....................................................... List of Public Universities in Kenya Public universities are government funded and Kenya has several as listed below: University of Nairobi (UoN) Founded in 1956, the University of Nairobi is the oldest and most prestigious University in Kenya. It has its main campus in the heart of Nairobi City, several campuses within the city and major towns across the country. It boasts of a great record of achievements over the years with several public figures, for instance, Deputy President, William Ruto, forming part of its alumni. Moi University The second university to be established in Kenya after Nairobi University, Moi University boasts of eight campuses and two constituent colleges. It was established in 1984 and is located in Eldoret. It has witnessed steady growth since its inception and still has more room for growth. It shares a name with Kenya’s second president, Daniel Moi. More Info: http://maisha.gradstate.com/complete-list-universities-in-kenya/ Kenyatta University (K.U) Commonly referred to as K.U, Kenyatta University, established in 1965, is the second largest university in Kenya. It is located along the Thika super highway with campuses within the Nairobi City and other towns in Kenya. Kenyatta University boasts of having the first female Vice Chancellor in Kenya, Dr. Olive Mugenda. It is good to note that Kenya’s 3rd president, Mwai Kibaki, went through Kenyatta University. Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT) With its main campus located in Juja town, along the Thika super highway, JKUAT as it is commonly known was started in 1981. -

Information Systems Education in Kenya: Students’ Specialization Choice Trends (A Case Study of Kenya Polytechnic University College)

International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 2013, Vol. 9, Issue 3, pp. 137-161 Information systems education in Kenya: Students’ specialization choice trends (a case study of Kenya Polytechnic University College) Atieno A. Ndede-Amadi Technical University of Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya ABSTRACT The objective of this study was to determine the time and level of Information Systems (IS) awareness among Kenyan university students and the choice of IS as a field of specialization. The study posited that the choice of a field of specialization is dependent upon a student’s awareness of its existence, its utilization in the real world, its career opportunities, and its strategic importance to the country’s economic development agenda. It posited further that early IS awareness could have a positive impact on the choice of IS as a field of specialization. The underlying assumptions were that the time of IS awareness as a field of specialization among Kenyan university business students was late and levels low, leading to possible low levels of choice of IS as a field of specialization. Using the survey method, the case study found late and low levels of IS awareness as a field of specialization among university business students. Future studies linking time and levels of IS awareness with choice of IS as a filed of specialization and with existence of requisite IS skills in the country (or lack thereof) are suggested. Keywords: Specialization, Awareness, Systems Analytical Skills, Joint Admissions Board, Public Universities, University Colleges, Parallel Programmes. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The History of Information Systems Although the history of Information Systems (IS) as a subject of study only spans six decades, it is among disciplines that have done much towards advancing development of the human race (Jorgenson and Vu, 2009). -

Examination Centres

NOVEMBER 2020 PREVIOUS AND REVISED EXAMINATION CENTRES Note: Where a candidate’s previously allocated centre is not in the revised list, Kasneb will strive to reallocate the candidate to the next nearest centre, subject to capacity. The shaded centres will not be available for November 2020. To know your previously allocated centre, send the word “Centre” with your registration number to 20558, for example Centre/NAC/your reg.no. In case you wish, due to unavoidable circumstances, to change your centre, send a request through an email to [email protected] with your reg no. and reasons, by Monday, 12 October 2020. Any such change will be subject to availability of capacity and will be communicated to students. Where you have not been allocated a centre and you paid, contact Kasneb immediately through email address [email protected] attaching relevant evidence. CENTRE CENTRE No. COUNTY PREVIOUS EXAMINATION CENTRES CODE COUNTY CURRENT EXAMINATION CENTRES CODE 1. BARINGO K. S. G - BARINGO 350 BARINGO K. S. G - BARINGO 350 BARTEK INSTITUTE – ELDAMA RAVINE 353 BARTEK INSTITUTE – ELDAMA RAVINE 353 2. BOMET BOMET COLLEGE OF ACCOUNTANCY 392 BOMET BOMET UNIVERSITY COLLEGE (PROPOSED) 525 SANG’ALO INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE AND 3. BUNGOMA TECHNOLOGY 338 BUNGOMA KIBABII UNIVERSITY 512 DOMINION TRAINING INSTITUTE - BUNGOMA 365 KIBABII UNIVERSITY 512 4. BUSIA YMCA BUSIA 349 BUSIA BUSIA DICECE (PROPOSED) 526 KCA UNIVERSITY - AMAGORO 509 EMBU JEREMIAH NYAGA TECHNICAL TRAINING 425 EMBU JEREMIAH NYAGA TECHNICAL TRAINING 425 INSTITUTE INSTITUTE 5. EMBU COLLEGE 439 EMBU COLLEGE 439 ACHIEVERS COLLEGE - EMBU 471 NORTH EASTERN NATIONAL NORTH EASTERN NATIONAL POLYTECHNIC - 6.