Lewis Carroll Society Meetings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SIX IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BEFORE BREAKFAST: THE LIFE AND MIND OF LEWIS CARROLL IN THE AGE OF ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MARY ALLEN SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kate Rosenberg Assistant Teaching Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes and offers connections between esteemed children’s literature author Lewis Carroll and the quality of mental state in which he was perceived by the public. Due to the imaginative nature of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it has been commonplace among scholars, students, readers, and most individuals familiar with the novel to wonder about the motive behind the unique perspective, or if the motive was ever intentional. This thesis explores the intentionality, or lack thereof, of the motives behind the novel along with elements of a close reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It additionally explores the origins of the concept of childhood along with the qualifications in relation to time period, culture, location, and age. It identifies common stereotypes and presumptions within the subject of mental illness. It aims to achieve a connection between the contents of Carroll’s novel with -

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

THE LAND BEYOND the MAGIC MIRROR by E

GREYHAWK CASTLE DUNGEON MODULE EX2 THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR by E. Gary Gygax AN ADVENTURE IN A WONDROUS PLACE FOR CHARACTER LEVELS 9-12 No matter the skill and experience of your party, they will find themselves dazed and challenged when they pass into The Land Beyond the Magic Mirror! Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc. and in Canada by Random House of Canada Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. Distributed in the United Kingdom by TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. AD&D and WORLD OF GREYHAWK are registered trademarks owned by TSR Hobbies, Inc. ©1983 TSR Hobbies, Inc. All Rights Reserved. TSR Hobbies, Inc. TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. POB 756 The Mill, Rathmore Road Lake Geneva, Cambridge CB14AD United Kingdom Printed in U.S.A. WI 53147 ISBN O 88038-025-X 9073 TABLE OF CONTENTS This module is the companion to Dungeonland and was originally part of the Greyhawk Castle dungeon complex. lt is designed so that it can be added to Dungeonland, used alone, or made part of virtually any campaign. It has an “EX” DUNGEON MASTERS PREFACE ...................... 2 designation to indicate that it is an extension of a regular THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR ............. 4 dungeon level—in the case of this module, a far-removed .................... extension where all adventuring takes place on another plane The Magic Mirror House First Floor 4 of existence that is quite unusual, even for a typical AD&D™ The Cellar ......................................... 6 Second Floor ...................................... 7 universe. This particular scenario has been a consistent ......................................... -

Lewis Carroll: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND by Lewis Carroll with fourty-two illustrations by John Tenniel This book is in public domain. No rigths reserved. Free for copy and distribution. This PDF book is designed and published by PDFREEBOOKS.ORG Contents Poem. All in the golden afternoon ...................................... 3 I Down the Rabbit-Hole .......................................... 4 II The Pool of Tears ............................................... 9 III A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale .................................. 14 IV The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill ................................. 19 V Advice from a Caterpillar ........................................ 25 VI Pig and Pepper ................................................. 32 VII A Mad Tea-Party ............................................... 39 VIII The Queen’s Croquet-Ground .................................... 46 IX The Mock Turtle’s Story ......................................... 53 X The Lobster Quadrille ........................................... 59 XI Who Stole the Tarts? ............................................ 65 XII Alice’s Evidence ................................................ 70 1 Poem All in the golden afternoon Of wonders wild and new, Full leisurely we glide; In friendly chat with bird or beast – For both our oars, with little skill, And half believe it true. By little arms are plied, And ever, as the story drained While little hands make vain pretence The wells of fancy dry, Our wanderings to guide. And faintly strove that weary one Ah, cruel Three! In such an hour, To put the subject by, Beneath such dreamy weather, “The rest next time –” “It is next time!” To beg a tale of breath too weak The happy voices cry. To stir the tiniest feather! Thus grew the tale of Wonderland: Yet what can one poor voice avail Thus slowly, one by one, Against three tongues together? Its quaint events were hammered out – Imperious Prima flashes forth And now the tale is done, Her edict ‘to begin it’ – And home we steer, a merry crew, In gentler tone Secunda hopes Beneath the setting sun. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Cast List- Alice in Wonderland Alice- Rachel M. Mathilda- Chynna A

Cast List- Alice in Wonderland Alice- Rachel M. Mathilda- Chynna A. Cheshire Cat 1- Jelayshia B. Cheshire Cat 2- Skylar B. Cheshire Cat 3- Shikirah H. White Rabbit- Cassie C. Doorknob- Mackenzie L. Dodo Bird- Latasia C. Rock Lobsters & Sea Creatures- Kayla M., Mariscia M., Bar’Shon B., Brandon E., Camryn M., Tyler B., Maniya T., Kaitlyn G., Destiney R., Sole’ H., Deja M. Tweedle Dee- Kayleigh F. Tweedle Dum- Tynigie R. Rose- Kristina M. Petunia- Cindy M. Lily- Katie B. Violet- Briana J. Daisy- Da’Johnna F. Flower Chorus- Keonia J., Shalaya F., Tricity R. and named flowers Caterpillar- Alex M. Mad Hatter- Andrew L. March Hare- Glenn F. Royal Cardsmen- ALL 3 Diamonds- Shemar H. 4 Spades- Aaron M. Ace Spades- Kevin T. 5 Diamonds- Abraham S. 2 Clubs- Ben S. Queen of Hearts- Alyceanna W. King of Hearts- Ethan G. Ensemble/Chorus- Katie B. Kevin T. Ben S. Briana J. Kristina M. Latasia C. Da’Johnna F. Shalaya F. Shamara H. Shemar H. Cindy M. Keonia J. Tricity R. Kaitlyn G. Sole’ H. Aaron M. Deja M. Destiney R. Abraham S. Chanyce S. Kayla M. Camryn M. Destiney A. Tyler B. Mariscia M. Brandon E. Bar’Shon B. Bridgette B. Maniya T. Amari L. Dodgsonland—ALL I’m Late—4th Very Good Advice—4th Grade Ocean of Tears—Dodo, Rock Lobsters, Sea Creatures (select 3rd and 4th) I’m Late-Reprise—4th How D’ye Do and Shakes Hands—Tweedles and Alice The Golden Afternoon—5th Grade girls Zip-a-dee-do-dah—4th and 5th The Unbirthday Song—5th Grade Painting the Roses Red—ALL Simon Says—Queen, Alice (ALL cardsmen) The Unbirthday Song-Reprise—Mad Hatter, Queen, King, 5th Grade Who Are You?—Tweedles, Flowers, Alice, Mad Hatter, White Rabbit, Queen & Named Cardsmen Alice in Wonderland: Finale—ALL Zip-a-dee-doo-dah: Bows—ALL . -

Humpty Dumpty's Explanation

Humpty Dumpty’s Explanation Humpty Dumpty’s explanation of the first verse of Jabberwocky from Through the Looking Glass and Alice’s Adventures there. 'You seem very clever at explaining words, Sir,' said Alice. 'Would you kindly tell me the meaning of the poem called "Jabberwocky"?' 'Let's hear it,' said Humpty Dumpty. 'I can explain all the poems that were ever invented--and a good many that haven't been invented just yet.' This sounded very hopeful, so Alice repeated the first verse: 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. 'That's enough to begin with,' Humpty Dumpty interrupted: 'there are plenty of hard words there. "BRILLIG" means four o'clock in the afternoon--the time when you begin BROILING things for dinner.' 'That'll do very well,' said Alice: and "SLITHY"?' 'Well, "SLITHY" means "lithe and slimy." "Lithe" is the same as "active." You see it's like a portmanteau--there are two meanings packed up into one word.' 'I see it now,' Alice remarked thoughtfully: 'and what are "TOVES"?' 'Well, "TOVES" are something like badgers--they're something like lizards--and they're something like corkscrews.' 'They must be very curious looking creatures.' 'They are that,' said Humpty Dumpty: 'also they make their nests under sun-dials--also they live on cheese.' 'Andy what's the "GYRE" and to "GIMBLE"?' 'To "GYRE" is to go round and round like a gyroscope. To "GIMBLE" is to make holes like a gimlet.' 1 'And "THE WABE" is the grass-plot round a sun-dial, I suppose?' said Alice, surprised at her own ingenuity. -

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios http://www.litgothic.com/Authors/saki.html Up to now, little has been known about Hector Hugh Munro except that he used the pen name “Saki”; that he wrote a number of witty short stories, two novels, several plays, and a history of Russia; and that he was killed in World War I. His friend Rothay Reynolds published “A Memoir of H. H. Munro” in Saki’s The Toys of Peace (1919), and Munro’s sister Ethel furnished a brief “Biography of Saki” for a posthumous collection of his work entitled The Square Egg and Other Sketches (1924). A. J. Langguth’s Saki is the first full-length biography of the man who, during his brief writing career, published a succession of bright, satirical, and sometimes perfectly crafted short stories that have entertained and amused readers in many countries for well over a half-century. Hector Munro was the third child of Charles Augustus Munro, a British police officer in Burma, and his wife Mary Frances. The children were all born in Burma. Pregnant with her fourth child, Mrs. Munro was brought with the children to live with her husband’s family in England until the child arrived. Frightened by the charge of a runaway cow on a country lane, Mrs. Munro died after a miscarriage. Since the widowed father had to return to Burma, the children — Charles, Ethel, and Hector — were left with their Munro grandmother and her two dominating and mutually antagonistic spinster daughters, Charlotte (“Aunt Tom”) and Augusta. This situation would years later provide incidents, characters, and themes for a number of Hector Munro’s short stories as well as this epitaph for Augusta by Ethel: “A woman of ungovernable temper, of fierce likes and dislikes, imperious, a moral coward, possessing no brains worth speaking of, and a primitive disposition. -

ALICE's ADVENTURES in WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, LA 70001 504-885-2000 www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher’s Notes………………………..…………..…………..……..3 Standards and Benchmarks…………………..……………….…..5 Background………………………………………..…….………………6 Alice’s Adventures, Comparing and Contrasting ………… 12 Art, Math and Set Design: Alice in Minecraft Land...................................................33 The Science of Color Meets the White Rabbit and the March Hare...................74 Additional Resources…………………………………..…..….….106 2 | P a g e Teacher’s Notes Music and Lyrics by Sammy Fain and Bob Hilliard, Oliver Wallace and Cy Coban, Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, Mack David, Al Hoffman and Jerry Livingston Music Adapted and Arranged and Additional Music and Lyrics by Bryan Louiselle Book Adapted and Additional Lyrics by David Simpatico Based on the 1951 Disney film, Alice in Wonderland, and the Lewis Carroll novels, "The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," Lewis Carroll's famous heroine comes to life in this delightful adaptation of the classic Disney film. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of Charles L. Dodgson. Born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury, Cheshire, England, Charles Dodgson wrote and created games as a child. At age 20 he received a studentship at Christ Church and was appointed a lecturer in mathematics. Dodgson was shy but enjoyed creating stories for children. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem,) probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method); some of this work was not published until well after his death. -

Submission and Agency, Or the Role of the Reader in the First Editions of Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderla

Submission and Agency, or the Role of the Reader in the First Editions of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871) Virginie Iché To cite this version: Virginie Iché. Submission and Agency, or the Role of the Reader in the First Editions of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871). Cahiers Victoriens et Edouardiens, Montpellier : Centre d’études et de recherches victoriennes et édouardiennes, 2016, 84, pp.Texte intégral en ligne. 10.4000/cve.2962. hal-03062880 HAL Id: hal-03062880 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03062880 Submitted on 27 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens 84 Automne | 2016 Object Lessons: The Victorians and the Material Text Submission and Agency, or the Role of the Reader in the First Editions of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through -

Alice in Wonderland (3)

Alice in Wonderland (3) Overview of chapters 7-12 Chapter 7: A Mad Tea Party Alice tries to take tea with the Hatter, the March Hare, and a Dormouse. She takes part in a confusing conversation and hears the beginning of the Dormouse’s tale. Madness: the Hatter and the Hare The Mad Hatter and the March Hare are another example of how in Wonderland language creates reality (rather than just reflecting it) “as mad as a hatter” (also because Victorian hatters worked with mercury, and mercury poisoning leads to insanity) Madness: the Hatter and the Hare “as mad as a March (>marsh?) hare” Tenniel drew the March Hare with wisps of straws on its head. This was a clear symbol of lunacy or insanity in the Victorian age. Unsurprisingly, Disney’s Hare does not retain any trace of the straws. A Mad Tea Party: a central chapter Alice reaches the furthest point in her descent into chaos: the word ‘mad’ is particularly prominent. The conversation at the tea table is absurd and aggressive, a parody perhaps of Victorian hypocrite ‘civil’ conversations during snobbish tea-parties. Alice’s puzzlement: the conversation “seemed to her to have no sort of meaning, and yet it was certainly English”. Agon at the tea table “Have some wine,” the March Hare said in an encouraging tone. [...] “I don’t see any wine,” she remarked. “There isn’t any,” said the March Hare. “Then it wasn’t very civil of you to offer it,” said Alice angrily. “It wasn’t very civil of you to sit down without being invited,” said the March Hare. -

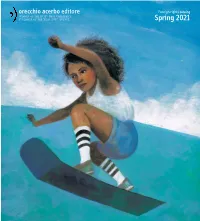

Orecchio Acerbo Rights List Spring 2021

orecchio acerbo editore Foreign rights catalog Winner of the BoP · Best Children’s PuBlisher of the Year 2017, euroPe Spring 2021 picture books daybrEak NEW by Daniel Fehr illustrations Elena Rotondo for children 4 years and older pp. 28 | cm. 23 x 21 ISBN 9788832070651 | July 2021 today NEW by Daniel Fehr big quEstioNs | grEat advENturEs illustrations Simone Rea WaitiNg for Walt for children 4 years and older by Daniel Fehr The story is about a young boy and his father. pp. 64 | cm. 17 x 24 illustrations Maja Celjia In the middle of the night they leave their house. ISBN 9788832070590 | April 2021 for children 5 years and older For the boy it is the first time that he leaves home pp. 32 | cm. 24 x 32 | May 2020 at this time of the night when normally uNdEr thE gazE of timE | rEcouNtiNg thE prEsENt he is asleep. As they walk through the forest storiEs of thE visioNary aNd thE absurd laughtEr aNd smilEs the flashlight of the boy “turns on” part A father who is leaving. Two brothers. A long wait. of the vegetation and at the same time the rest But together it is easier, together it is easy disappear. He turns off the flashlight and “turns on” to be strong. The older brother reads books Two kids are waiting for Walt. But who is Walt? all his senses: he experiences the darkness, to the younger one who can’t read yet but can And, if Walt was there with them, what would the sounds of the forest, the sound of his father, at least choose the book; then they go together they all do together? They would have a lot the roughness of the ground, the smells… on a secret mission: is every mission of spies of fun, because when he is there he always He dares not ask for the space and time secret? Then one goes to play football, the other has crazy ideas.