Barite Travertine from Southwestern Oklahoma and West - Central Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Processing

Mineral Processing Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy 1st English edition JAN DRZYMALA, C. Eng., Ph.D., D.Sc. Member of the Polish Mineral Processing Society Wroclaw University of Technology 2007 Translation: J. Drzymala, A. Swatek Reviewer: A. Luszczkiewicz Published as supplied by the author ©Copyright by Jan Drzymala, Wroclaw 2007 Computer typesetting: Danuta Szyszka Cover design: Danuta Szyszka Cover photo: Sebastian Bożek Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej Wybrzeze Wyspianskiego 27 50-370 Wroclaw Any part of this publication can be used in any form by any means provided that the usage is acknowledged by the citation: Drzymala, J., Mineral Processing, Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy, Oficyna Wydawnicza PWr., 2007, www.ig.pwr.wroc.pl/minproc ISBN 978-83-7493-362-9 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 Part I Introduction to mineral processing .....................................................................13 1. From the Big Bang to mineral processing................................................................14 1.1. The formation of matter ...................................................................................14 1.2. Elementary particles.........................................................................................16 1.3. Molecules .........................................................................................................18 1.4. Solids................................................................................................................19 -

Oil Shale, Part II: Geology and Mineralogy of the Oil Shales of the Green River Formation, Colorado, Utah and Wyoming

Article Oil shale, part II: geology and mineralogy of the oil shales of the Green River formation, Colorado, Utah and Wyoming JAFFE, Felice Reference JAFFE, Felice. Oil shale, part II: geology and mineralogy of the oil shales of the Green River formation, Colorado, Utah and Wyoming. Colorado School of Mines Mineral Industries Bulletin, 1962, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 1-16 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:152772 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 b ~L~ ~· () ~~ ,~Ov. (i) ~ COLORADO SCHOOL OF MIN~JT\-:-~----~1 Mi n e r a I/I nd u s t r, ie s B.u 11 e.t i n The Colorado School of Mines Mineral Industries Bulletin is published every other month by the Colorado School of Mines Research Foundation to inform those interested in the mineral industry regarding the elements of the geology and mineral resources, mining operations, metal markets, production statistics, economics, and other aspects of the mineral industry. This publication may be obtained for a yearly subscription charge af $1.00 for the six issues pub- lished from July through May of the following year. Past issues still in print may be had for 25c each. Address your order to the Department of Publica- tions, Colorado School af Mines, Golden, Colorado. Entered as second class matter at the Post Office at Golden, Colorado, under Act of Congress, July 16, 1894. Copyright 1962 by The Colorado School of Mines. All rights reserved. This publication or any part of it may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the Colorado School af Mines. -

World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014 International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps

ISSN 0532-0488 WORLD SOIL RESOURCES REPORTS 106 World reference base for soil resources 2014 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps Update 2015 Cover photographs (left to right): Ekranic Technosol – Austria (©Erika Michéli) Reductaquic Cryosol – Russia (©Maria Gerasimova) Ferralic Nitisol – Australia (©Ben Harms) Pellic Vertisol – Bulgaria (©Erika Michéli) Albic Podzol – Czech Republic (©Erika Michéli) Hypercalcic Kastanozem – Mexico (©Carlos Cruz Gaistardo) Stagnic Luvisol – South Africa (©Márta Fuchs) Copies of FAO publications can be requested from: SALES AND MARKETING GROUP Information Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Viale delle Terme di Caracalla 00100 Rome, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (+39) 06 57053360 Web site: http://www.fao.org WORLD SOIL World reference base RESOURCES REPORTS for soil resources 2014 106 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps Update 2015 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

Barite (Barium)

Barite (Barium) Chapter D of Critical Mineral Resources of the United States—Economic and Environmental Geology and Prospects for Future Supply Professional Paper 1802–D U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Periodic Table of Elements 1A 8A 1 2 hydrogen helium 1.008 2A 3A 4A 5A 6A 7A 4.003 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 lithium beryllium boron carbon nitrogen oxygen fluorine neon 6.94 9.012 10.81 12.01 14.01 16.00 19.00 20.18 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 sodium magnesium aluminum silicon phosphorus sulfur chlorine argon 22.99 24.31 3B 4B 5B 6B 7B 8B 11B 12B 26.98 28.09 30.97 32.06 35.45 39.95 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 potassium calcium scandium titanium vanadium chromium manganese iron cobalt nickel copper zinc gallium germanium arsenic selenium bromine krypton 39.10 40.08 44.96 47.88 50.94 52.00 54.94 55.85 58.93 58.69 63.55 65.39 69.72 72.64 74.92 78.96 79.90 83.79 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 rubidium strontium yttrium zirconium niobium molybdenum technetium ruthenium rhodium palladium silver cadmium indium tin antimony tellurium iodine xenon 85.47 87.62 88.91 91.22 92.91 95.96 (98) 101.1 102.9 106.4 107.9 112.4 114.8 118.7 121.8 127.6 126.9 131.3 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 cesium barium hafnium tantalum tungsten rhenium osmium iridium platinum gold mercury thallium lead bismuth polonium astatine radon 132.9 137.3 178.5 180.9 183.9 186.2 190.2 192.2 195.1 197.0 200.5 204.4 207.2 209.0 (209) (210)(222) 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 -

Selective Flotation of Witherite from Calcite Using Potassium Chromate As a Depressant

Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process., 55(2), 2019, 565-574 Physicochemical Problems of Mineral Processing ISSN 1643-1049 http://www.journalssystem.com/ppmp © Wroclaw University of Science and Technology Received May 31, 2018; reviewed; accepted September 2, 2018 Selective flotation of witherite from calcite using potassium chromate as a depressant Yangshuai Qiu 1, Lingyan Zhang 1,2, Xuan Jiao 1, Junfang Guan 1,2, Ye Li 1,2, Yupeng Qian 1,2 1 School of Resources and Environmental Engineering, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan 430070, China 2 Hubei Key Laboratory of Mineral Resources Processing & Environment, Wuhan 430070, China Corresponding author: [email protected] (Lingyan Zhang) Abstract: Witherite has been widely used as an industrial and environmental source of barium, with calcite being the primary associated carbonate mineral. However, few studies have been conducted to effectively concentrate witherite from barium ores. In this work, with the treatment of potassium chromate (K2CrO4) and sodium oleate (NaOL), witherite was selectively separated from calcite through selective flotation at different pH conditions. In addition, contact angle, Zeta potential, adsorption and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy measurements were performed to characterize the separation mechanisms. The results demonstrated that NaOL had a strong collecting ability for both witherite and calcite; nevertheless, witherite could be effectively selected from calcite with the highest recovery at pH 9 in the presence of K2CrO4. From the XPS measurements, NaOL and K2CrO4 were found to be primarily attached to the surfaces of witherite and calcite through chemisorption. The presence of K2CrO4 on the surface of calcite adversely influenced the NaOL adsorption, which could make the flotation separation efficient and successful. -

Infrare D Transmission Spectra of Carbonate Minerals

Infrare d Transmission Spectra of Carbonate Mineral s THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM Infrare d Transmission Spectra of Carbonate Mineral s G. C. Jones Department of Mineralogy The Natural History Museum London, UK and B. Jackson Department of Geology Royal Museum of Scotland Edinburgh, UK A collaborative project of The Natural History Museum and National Museums of Scotland E3 SPRINGER-SCIENCE+BUSINESS MEDIA, B.V. Firs t editio n 1 993 © 1993 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht Originally published by Chapman & Hall in 1993 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1993 Typese t at the Natura l Histor y Museu m ISBN 978-94-010-4940-5 ISBN 978-94-011-2120-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-011-2120-0 Apar t fro m any fair dealin g for the purpose s of researc h or privat e study , or criticis m or review , as permitte d unde r the UK Copyrigh t Design s and Patent s Act , 1988, thi s publicatio n may not be reproduced , stored , or transmitted , in any for m or by any means , withou t the prio r permissio n in writin g of the publishers , or in the case of reprographi c reproductio n onl y in accordanc e wit h the term s of the licence s issue d by the Copyrigh t Licensin g Agenc y in the UK, or in accordanc e wit h the term s of licence s issue d by the appropriat e Reproductio n Right s Organizatio n outsid e the UK. Enquirie s concernin g reproductio n outsid e the term s state d here shoul d be sent to the publisher s at the Londo n addres s printe d on thi s page. -

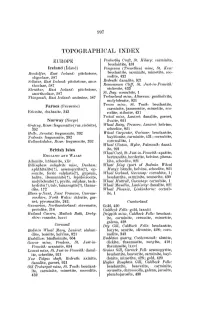

Topographical Index

997 TOPOGRAPHICAL INDEX EUROPE Penberthy Croft, St. Hilary: carminite, beudantite, 431 Iceland (fsland) Pengenna (Trewethen) mine, St. Kew: Bondolfur, East Iceland: pitchsbone, beudantite, carminite, mimetite, sco- oligoclase, 587 rodite, 432 Sellatur, East Iceland: pitchs~one, anor- Redruth: danalite, 921 thoclase, 587 Roscommon Cliff, St. Just-in-Peuwith: Skruthur, East Iceland: pitchstonc, stokesite, 433 anorthoclase, 587 St. Day: cornubite, 1 Thingmuli, East Iceland: andesine, 587 Treburland mine, Altarnun: genthelvite, molybdenite, 921 Faroes (F~eroerne) Treore mine, St. Teath: beudantite, carminite, jamesonite, mimetite, sco- Erionite, chabazite, 343 rodite, stibnite, 431 Tretoil mine, Lanivet: danalite, garnet, Norway (Norge) ilvaite, 921 Gryting, Risor: fergusonite (var. risSrite), Wheal Betsy, Tremore, Lanivet: he]vine, 392 scheelite, 921 Helle, Arendal: fergusonite, 392 Wheal Carpenter, Gwinear: beudantite, Nedends: fergusonite, 392 bayldonite, carminite, 431 ; cornubite, Rullandsdalen, Risor: fergusonite, 392 cornwallite, 1 Wheal Clinton, Mylor, Falmouth: danal- British Isles ire, 921 Wheal Cock, St. Just-in- Penwith : apatite, E~GLA~D i~D WALES bertrandite, herderite, helvine, phena- Adamite, hiibnerite, xliv kite, scheelite, 921 Billingham anhydrite mine, Durham: Wheal Ding (part of Bodmin Wheal aph~hitalite(?), arsenopyrite(?), ep- Mary): blende, he]vine, scheelite, 921 somite, ferric sulphate(?), gypsum, Wheal Gorland, Gwennap: cornubite, l; halite, ilsemannite(?), lepidocrocite, beudantite, carminite, zeunerite, 430 molybdenite(?), -

Sodium Sulphate: Its Sources and Uses

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Bulletin 717 SODIUM SULPHATE: ITS SOURCES AND USES BY ROGER C. WELLS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1 923 - , - _, v \ w , s O ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE PBOCUKED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 5 CENTS PEE COPY PURCHASER AGREES NOT TO RESELL OR DISTRIBUTE THIS COPY FOR PROFIT. PUB. RES. 57, APPROVED MAY 11, 1922 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction ____ _____ ________________ 1 Demand 1 Forms ____ __ __ _. 1 Uses . 1 Mineralogy of principal compounds of sodium sulphate _ 2 Mirabilite_________________________________ 2 Thenardite__ __ _______________ _______. 2 Aphthitalite_______________________________ 3 Bloedite __ __ _________________. 3 Glauberite ____________ _______________________. 4- Hanksite __ ______ ______ ___________ 4 Miscellaneous minerals _ __________ ______ 5 Solubility of sodium sulphate *.___. 5 . Transition temperature of sodium sulphate______ ___________ 6 Reciprocal salt pair, sodium sulphate and potassium chloride____ 7 Relations at 0° C___________________________ 8 Relations at 25° C__________________________. 9 Relations at 50° C__________________________. 10 Relations at 75° and 100° C_____________________ 11 Salt cake__________ _.____________ __ 13 Glauber's salt 15 Niter cake_ __ ____ ______ 16 Natural sodium sulphate _____ _ _ __ 17 Origin_____________________________________ 17 Deposits __ ______ _______________ 18 Arizona . 18 -

New Insights on Secondary Minerals from Italian Sulfuric Acid Caves Ilenia M

International Journal of Speleology 47 (3) 271-291 Tampa, FL (USA) September 2018 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs International Journal of Speleology Off icial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie New insights on secondary minerals from Italian sulfuric acid caves Ilenia M. D’Angeli1*, Cristina Carbone2, Maria Nagostinis1, Mario Parise3, Marco Vattano4, Giuliana Madonia4, and Jo De Waele1 1Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences, University of Bologna, Via Zamboni 67, 40126 Bologna, Italy 2DISTAV, Department of Geological, Environmental and Biological Sciences, University of Genoa, Corso Europa 26, 16132 Genova, Italy 3Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Piazza Umberto I 1, 70121 Bari, Italy 4Department of Earth and Marine Sciences, University of Palermo, Via Archirafi 22, 90123 Palermo, Italy Abstract: Sulfuric acid minerals are important clues to identify the speleogenetic phases of hypogene caves. Italy hosts ~25% of the known worldwide sulfuric acid speleogenetic (SAS) systems, including the famous well-studied Frasassi, Monte Cucco, and Acquasanta Terme caves. Nevertheless, other underground environments have been analyzed, and interesting mineralogical assemblages were found associated with peculiar geomorphological features such as cupolas, replacement pockets, feeders, sulfuric notches, and sub-horizontal levels. In this paper, we focused on 15 cave systems located along the Apennine Chain, in Apulia, in Sicily, and in Sardinia, where copious SAS minerals were observed. Some of the studied systems (e.g., Porretta Terme, Capo Palinuro, Cassano allo Ionio, Cerchiara di Calabria, Santa Cesarea Terme) are still active, and mainly used as spas for human treatments. The most interesting and diversified mineralogical associations have been documented in Monte Cucco (Umbria) and Cavallone-Bove (Abruzzo) caves, in which the common gypsum is associated with alunite-jarosite minerals, but also with baryte, celestine, fluorite, and authigenic rutile-ilmenite-titanite. -

Neighborite Namgf3

Neighborite NaMgF3 Crystal Data: Orthorhombic, pseudocubic. Point Group: 2/m 2/m 2/m. As pseudo-octahedral or pseudocubic crystals, to 3 mm, and as oblong to rounded grains. Twinning: Polysynthetic and interpenetrant, complex but poorly defined. Physical Properties: Fracture: Uneven. Hardness = 4.5 D(meas.) = 3.03(3) D( calc.) = 3.08 Optical Properties: Transparent to opaque. Color: Colorless, cream, pink, red, brown, may be zoned. Luster: Vitreous to dull, greasy. Optical Class: Isotropic, with birefringence = ~0.003. n = 1.364(2) Cell Data: Space Group: Pbnm. a = 5.352(1) b = 7.485(1) c = 7.663(2) Z = 4 X-ray Powder Pattern: South Ouray, Utah, USA. 1.918 (100), 2.71 (50) ,3.83 (35), 2.30 (25), 1.556 (25), 2.23 (18), 2.20 (13) Chemistry: (1) (2) Fe2O3 0.17 MgO 39.36 38.65 CaO 1.10 Na2O 27.02 29.71 K2O 0.77 F 54.76 54.65 H2O 0.25 - O = F2 [23.06] 23.01 Total [100.37] 100.00 (1) Ural Mountains, Russia; original total given as 100.49%; corresponds to (Na0.87K0.02)Σ=0.89 (Mg0.98Ca0.02)Σ=1.00F2.97. (2) NaMgF3. Occurrence: An authigenic mineral, formed under aluminum-deficient conditions in dolomitic oil shale (South Ouray, Utah, USA); in metamorphosed tuff and clayey carbonate sediments (Ural Mountains, Russia); in miarolitic cavities in peralkalic granite (Lake Gjerdingen, Norway); in cavities in pegmatite and hornfels in an alkalic gabbro-syenite complex (Mont Saint- Hilaire). Association: Burbankite, nahcolite, wurtzite, barytocalcite, garrelsite, pyrite, calcite, quartz (South Ouray, Utah, USA); quartz, aegirine, rhodochrosite, zircon, fluorite, gagarinite, monazite-(Ce), galena, sphalerite, molybdenite, brookite (Gjerdingen, Nordmarka, Norway). -

A Specific Gravity Index for Minerats

A SPECIFICGRAVITY INDEX FOR MINERATS c. A. MURSKyI ern R. M. THOMPSON, Un'fuersityof Bri.ti,sh Col,umb,in,Voncouver, Canad,a This work was undertaken in order to provide a practical, and as far as possible,a complete list of specific gravities of minerals. An accurate speciflc cravity determination can usually be made quickly and this information when combined with other physical properties commonly leads to rapid mineral identification. Early complete but now outdated specific gravity lists are those of Miers given in his mineralogy textbook (1902),and Spencer(M,i,n. Mag.,2!, pp. 382-865,I}ZZ). A more recent list by Hurlbut (Dana's Manuatr of M,i,neral,ogy,LgE2) is incomplete and others are limited to rock forming minerals,Trdger (Tabel,l,enntr-optischen Best'i,mmungd,er geste,i,nsb.ildend,en M,ineral,e, 1952) and Morey (Encycto- ped,iaof Cherni,cal,Technol,ogy, Vol. 12, 19b4). In his mineral identification tables, smith (rd,entifi,cati,onand. qual,itatioe cherai,cal,anal,ys'i,s of mineral,s,second edition, New york, 19bB) groups minerals on the basis of specificgravity but in each of the twelve groups the minerals are listed in order of decreasinghardness. The present work should not be regarded as an index of all known minerals as the specificgravities of many minerals are unknown or known only approximately and are omitted from the current list. The list, in order of increasing specific gravity, includes all minerals without regard to other physical properties or to chemical composition. The designation I or II after the name indicates that the mineral falls in the classesof minerals describedin Dana Systemof M'ineralogyEdition 7, volume I (Native elements, sulphides, oxides, etc.) or II (Halides, carbonates, etc.) (L944 and 1951). -

The Crystal Structure of Alstonite, Baca(CO3)2: an Extraordinary Example of ‘Hidden’ Complex Twinning in Large Single Crystals

Mineralogical Magazine (2020), 84, 699–704 doi:10.1180/mgm.2020.61 Article The crystal structure of alstonite, BaCa(CO3)2: an extraordinary example of ‘hidden’ complex twinning in large single crystals Luca Bindi1* , Andrew C. Roberts2 and Cristian Biagioni3 1Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Firenze, Via G. La Pira 4, I-50121 Firenze, Italy; 2Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth Street, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E8, Canada; and 3Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Pisa, Via S. Maria 53, I-56126 Pisa, Italy Abstract Alstonite, BaCa(CO3)2, is a mineral described almost two centuries ago. It is widespread in Nature and forms magnificent cm-sized crystals. Notwithstanding, its crystal structure was still unknown. Here, we report the crystal-structure determination of the mineral and discuss it in relationship to other polymorphs of BaCa(CO3)2. Alstonite is trigonal, space group P31m, with unit-cell parameters 3 a = 17.4360(6), c = 6.1295(2) Å, V = 1613.80(9) Å and Z = 12. The crystal structure was solved and refined to R1 = 0.0727 on the σ c basis of 4515 reflections with Fo >4 (Fo) and 195 refined parameters. Alstonite is formed by the alternation, along , of Ba-dominant and Ca-dominant layers, separated by CO3 groups parallel to {0001}. The main take-home message is to show that not all structure determinations of minerals/compounds can be solved routinely. Some crystals, even large ones displaying excellent diffraction quality, can be twinned in complex ways, thus making their study a crystallographic challenge. Keywords: alstonite, carbonate, barium, calcium, crystal structure, twinning (Received 11 June 2020; accepted 25 July 2020; Accepted Manuscript published online: 29 July 2020; Associate Editor: Charles A Geiger) Introduction b = 17.413(5), c = 6.110(1) Å and β = 90.10(1)°, with a unit-cell volume 12 times larger than the orthorhombic cell proposed by Alstonite, BaCa(CO ) , is polymorphous with barytocalcite, para- 3 2 Gossner and Mussgnug (1930).