Working Papers in Economic History the Roots of Land Inequality in Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Focusthe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief

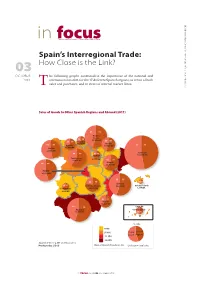

CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona in focusThe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief Spain’s Interregional Trade: 03 How Close is the Link? OCTOBER he following graphs contextualise the importance of the national and 2012 international market for the 17 dif ferent Spanish regions, in terms of both T sales and purchases, and in terms of internal market flows. Sales of Goods to Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) 46 54 Basque County 36 64 45,768 M€ 33 67 Cantabria 45 55 7,231 M€ Navarre 54 46 Asturias 17,856 M€ 53 47 Galicia 11,058 M€ 32,386 M€ 40 60 31 69 Catalonia La Rioja 104,914 M€ Castile-Leon 4,777 M€ 30,846 M€ 39 61 Aragon 54 46 23,795 M€ Madrid 45,132 M€ 45 55 22 78 5050 Valencia 29 71 Castile-La Mancha 44,405 M€ Balearic Islands Extremaura 18,692 M€ 1,694 M€ 4,896 M€ 39 61 Murcia 14,541 M€ 44 56 4,890 M€ Andalusia Canary Islands 52,199 M€ 49 51 % Sales 0-4% 5-10% To the Spanish World Regions 11-15% 16-20% Source: C-Intereg, INE and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB Share of Spanish Population (%) Circle Size = Total Sales in focus CIDOB 03 . OCTOBER 2012 CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona Purchase of Goods From Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) Basque County 28 72 36 64 35,107 M€ 35 65 Asturias Cantabria Navarre 11,580 M€ 55 45 6,918 M€ 14,914 M€ 73 27 Galicia 29 71 25,429 M€ 17 83 Catalonia Castile-Leon La Rioja 97,555 M€ 34,955 M€ 29 71 6,498 M€ Aragon 67 33 26,238 M€ Madrid 79,749 M€ 44 56 2 78 Castile-La Mancha Valencia 19 81 12 88 23,540 M€ Extremaura 49 51 45,891 M€ Balearic Islands 8,132 M€ 8,086 M€ 54 46 Murcia 18,952 M€ 56 44 Andalusia 52,482 M€ Canary Islands 35 65 13,474 M€ Purchases from 27,000 to 31,000 € 23,000 to 27,000 € Rest of Spain 19,000 to 23,000 € the world 15,000 to 19,000 € GDP per capita Circle Size = Total Purchase Source: C-Intereg, Expansión and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB 2 in focus CIDOB 03 . -

The Beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e21 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia * Dimas Martín-Socas a, , María Dolores Camalich Massieu a, Jose Luis Caro Herrero b, F. Javier Rodríguez-Santos c a U.D.I. de Prehistoria, Arqueología e Historia Antigua (Dpto. Geografía e Historia), Universidad de La Laguna, Campus Guajara, 38071 Tenerife, Spain b Dpto. Lenguajes y Ciencias de la Computacion, Universidad de Malaga, Complejo Tecnologico, Campus de Teatinos, 29071 Malaga, Spain c Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistoricas de Cantabria (IIIPC), Universidad de Cantabria. Edificio Interfacultativo, Avda. Los Castros, 52. 39005 Santander, Spain article info abstract Article history: The Early Neolithic in Andalusia shows great complexity in the implantation of the new socioeconomic Received 31 January 2017 structures. Both the wide geophysical diversity of this territory and the nature of the empirical evidence Received in revised form available hinder providing a general overview of when and how the Mesolithic substrate populations 6 June 2017 influenced this process of transformation, and exactly what role they played. The absolute datings Accepted 22 June 2017 available and the studies on the archaeological materials are evaluated, so as to understand the diversity Available online xxx of the different zones undergoing the neolithisation process on a regional scale. The results indicate that its development, initiated in the middle of the 6th millennium BC and consolidated between 5500 and Keywords: Iberian Peninsula 4700 cal. BC, is parallel and related to the same changes documented in North Africa and the different Andalusia areas of the Central-Western Mediterranean. -

Cantabria Y Asturias Seniors 2016·17

Cantabria y Asturias Seniors 2016·17 7 días / 6 noches Hotel Zabala 3* (Santillana del Mar) € Hotel Norte 3* (Gijón) desde 399 Salida: 11 de junio Precio por persona en habitación doble Suplemento Hab. individual: 150€ ¡TODO INCLUIDO! 13 comidas + agua/vino + excursiones + entradas + guías ¿Por qué reservar este viaje? ¿Quiere conocer Cantabria y Asturias? En nuestro circuito Reserve por sólo combinamos lo mejor de estas dos comunidades para que durante 7 días / 6 noches conozcas a fondo los mejores rincones de la geografía. 50 € Itinerario: Incluimos: DÍA 1º. BARCELONA – CANTABRIA • Asistencia por personal de Viajes Tejedor en el punto de salida. Salida desde Barcelona. Breves paradas en ruta (almuerzo en restaurante incluido). • Autocar y guía desde Barcelona y durante todo el recorrido. Llegada al hotel en Cantabria. Cena y alojamiento. • 3 noches de alojamiento en el hotel Zabala 3* de Santillana del Mar y 2 noches en el hotel Norte 3* de Gijón. DÍA 2º. VISITA DE SANTILLANA DEL MAR y COMILLAS – VISITA DE • 13 comidas con agua/vino incluido, según itinerario. SANTANDER • Almuerzos en ruta a la ida y regreso. Desayuno. Seguidamente nos dirigiremos a la localidad de Santilla del Mar. Histórica • Visitas a: Santillana del Mar, Comillas, Santander, Santoña, Picos de Europa, Potes, población de gran belleza, donde destaca la Colegiata románica del S.XII, declarada Oviedo, Villaviciosa, Lastres, Tazones, Avilés, Luarca y Cudillero. Monumento Nacional. Las calles empedradas y las casas blasonadas, configuran un paisaje • Pasaje de barco de Santander a Somo. urbano de extraordinaria belleza. Continuaremos viaje a la cercana localidad de Comillas, • Guías locales en: Santander, Oviedo y Avilés. -

To the West of Spanish Cantabria. the Palaeolithic Settlement of Galicia

To the West of Spanish Cantabria. The Palaeolithic Settlement of Galicia Arturo de Lombera Hermida and Ramón Fábregas Valcarce (eds.) Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011, 143 pp. (paperback), £29.00. ISBN-13: 97891407308609. Reviewed by JOÃO CASCALHEIRA DNAP—Núcleo de Arqueologia e Paleoecologia, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade do Algarve, Campus Gambelas, 8005- 138 Faro, PORTUGAL; [email protected] ompared with the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, Galicia investigation, stressing the important role of investigators C(NW Iberia) has always been one of the most indigent such as H. Obermaier and K. Butzer, and ending with a regions regarding Paleolithic research, contrasting pro- brief presentation of the projects that are currently taking nouncedly with the neighboring Cantabrian rim where a place, their goals, and auspiciousness. high number of very relevant Paleolithic key sequences are Chapter 2 is a contribution of Pérez Alberti that, from known and have been excavated for some time. a geomorphological perspective, presents a very broad Up- This discrepancy has been explained, over time, by the per Pleistocene paleoenvironmental evolution of Galicia. unfavorable geological conditions (e.g., highly acidic soils, The first half of the paper is constructed almost like a meth- little extension of karstic formations) of the Galician ter- odological textbook that through the definition of several ritory for the preservation of Paleolithic sites, and by the concepts and their applicability to the Galician landscape late institutionalization of the archaeological studies in supports the interpretations outlined for the regional inter- the region, resulting in an unsystematic research history. land and coastal sedimentary sequences. As a conclusion, This scenario seems, however, to have been dramatically at least three stadial phases were identified in the deposits, changed in the course of the last decade. -

Chapter 24. the BAY of BISCAY: the ENCOUNTERING of the OCEAN and the SHELF (18B,E)

Chapter 24. THE BAY OF BISCAY: THE ENCOUNTERING OF THE OCEAN AND THE SHELF (18b,E) ALICIA LAVIN, LUIS VALDES, FRANCISCO SANCHEZ, PABLO ABAUNZA Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO) ANDRE FOREST, JEAN BOUCHER, PASCAL LAZURE, ANNE-MARIE JEGOU Institut Français de Recherche pour l’Exploitation de la MER (IFREMER) Contents 1. Introduction 2. Geography of the Bay of Biscay 3. Hydrography 4. Biology of the Pelagic Ecosystem 5. Biology of Fishes and Main Fisheries 6. Changes and risks to the Bay of Biscay Marine Ecosystem 7. Concluding remarks Bibliography 1. Introduction The Bay of Biscay is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean, indenting the coast of W Europe from NW France (Offshore of Brittany) to NW Spain (Galicia). Tradition- ally the southern limit is considered to be Cape Ortegal in NW Spain, but in this contribution we follow the criterion of other authors (i.e. Sánchez and Olaso, 2004) that extends the southern limit up to Cape Finisterre, at 43∞ N latitude, in order to get a more consistent analysis of oceanographic, geomorphological and biological characteristics observed in the bay. The Bay of Biscay forms a fairly regular curve, broken on the French coast by the estuaries of the rivers (i.e. Loire and Gironde). The southeastern shore is straight and sandy whereas the Spanish coast is rugged and its northwest part is characterized by many large V-shaped coastal inlets (rias) (Evans and Prego, 2003). The area has been identified as a unit since Roman times, when it was called Sinus Aquitanicus, Sinus Cantabricus or Cantaber Oceanus. The coast has been inhabited since prehistoric times and nowadays the region supports an important population (Valdés and Lavín, 2002) with various noteworthy commercial and fishing ports (i.e. -

Six Rer11i Nders ; ··· ·' F.!5 Tra~ Vellers ...· R"I

Ricardo Castto ~ t' I l .,l "t :: lar, ; I ; six rer11i nders ; ··· ·' f.!5 tra~ vellers ...· r"i. ~ >~,· ; . ;r. :,I 26 The Fifth Column Ricar<Jo Castro Dl WACKISE £T lDIT 0 0 volume eight, nwnber three on the rood .. 27 Ricardo Casrro SIX REMINDERS FOR TRAVELLERS. Canals, Spanish canals, particularly the Canal de Castilla. Spain is engraved with canals. Transport, (exchange of goods, displacement of people) and irrigation, (movernem or dispersion of water) are, separately or combined, the two main drivmg forces for the construction of canals. A variety of minor works and utopian projects were begun and promoted as early as the first part of the sixteenth century, a time during which Spain began its political consolidation undec the Catholic Kings. A few years later, between 1548 and 1550, during the reign of Maximillian of Austria interest in fluvial navigation in Spain became a renewed imperative. It is from this time, for instance, that the first Spanish extant drawing of a revolving lock: which closed with the aid of the current, comes to us•. But it is only in the mid- eighteenth century, during the reign of Ferdinand VI, that the first major navigable-irrigation waterworks, the Canal de Castilla and the Imperial Canal of Arag6n, were bwlL Both canals, among the most extraordinary hydraulic monuments of Spain, fonn part of the extensive series of public works including roads, dams, docks, bridges, silos, hospitals, schools and even bullfight rings, initiated and promoted during the Spanish Enlightenment (La Uustraci6n Espai'lola). They would play a more significant role during the nineteenth century. -

IRS 2016 Proposal Valladolid, Spain

CANDIDATE TECHNICAL DOSSIER FOR International Radiation Symposium IRS2016 In VALLADOLID (SPAIN), August 2016 Grupo de Optica Atmosférica, GOA-UVA Universidad de Valladolid Castilla y León Spain 1 INDEX I. Introduction…………………………………………………………............. 3 II. Motivation/rationale for holding the IRS in Valladolid………………....….. 3 III. General regional and local interest. Community of Castilla y León…......... 4 IV. The University of Valladolid, UVA. History and Infrastructure………….. 8 V. Conference environment …………………………………………………. 15 VI. Venue description and capacity. Congress Centre Auditorium …….…… 16 VII. Local sites of interest, universities, museums, attractions, parks etc …... 18 VIII. VISA requirements …………………………………………………….. 20 2 IRS’ 2016, Valladolid, Spain I. Introduction We are pleased to propose and host the next IRS at Valladolid, Spain, in August of 2016, to be held at the Valladolid Congress Centre, Avenida de Ramón Pradera, 47009 Valladolid, Spain. A view of the city of Valladolid with the Pisuerga river II. Motivation/rationale for holding the IRS in Valladolid Scientific Interest In the last decades, Spain has experienced a great growth comparatively to other countries in Europe and in the world, not only in the social and political aspects but also in the scientific research. Certainly Spain has a medium position in the world but it potential increases day by day. The research in Atmospheric Sciences has not a long tradition in our country, but precisely, its atmospheric conditions and geographical location makes it one of the best places for atmospheric studies, in topics as radiation, aerosols, etc…. , being a special region in Europe to analyse the impact of climate change. Hosting the IRS’2016 for the first time in Spain would produce an extraordinary benefit for all the Spanish scientific community, and particularly for those groups working in the atmospheric, meteorological and optics research fields. -

33 the Radiocarbon Chronology of El Mirón Cave

RADIOCARBON, Vol 52, Nr 1, 2010, p 33–39 © 2010 by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona THE RADIOCARBON CHRONOLOGY OF EL MIRÓN CAVE (CANTABRIA, SPAIN): NEW DATES FOR THE INITIAL MAGDALENIAN OCCUPATIONS Lawrence Guy Straus1,2 • Manuel R González Morales2 ABSTRACT. Three additional radiocarbon assays were run on samples from 3 levels lying below the classic (±15,500 BP) Lower Cantabrian Magdalenian horizon in the outer vestibule excavation area of El Mirón Cave in the Cantabrian Cordillera of northern Spain. Although the central tendencies of the new dates are out of stratigraphic order, they are consonant with the post-Solutrean, Initial Magdalenian period both in El Mirón and in the Cantabrian region, indicating a technological transition in preferred weaponry from foliate and shouldered points to microliths and antler sagaies between about 17,000–16,000 BP (uncalibrated), during the early part of the Oldest Dryas pollen zone. Now with 65 14C dates, El Mirón is one of the most thor- oughly dated prehistoric sites in western Europe. The until-now poorly dated, but very distinctive Initial Cantabrian Magdale- nian lithic artifact assemblages are briefly summarized. INTRODUCTION El Mirón Cave is located in the upper valley of the Asón River in eastern Cantabria Province in northern Spain, about 100 m up from the valley floor on the steep western face of a mountain in the second foothill range of the Cantabrian Cordillera, about halfway between the cities of Santander and Bilbao. The site location in the town of Ramales de la Victoria (431448N, 3275W) is 260 m above present sea level, and about 20 km from the present shore of the Bay of Biscay (and about 25–30 km from the Tardiglacial shore). -

Q4 2020: the Slow Path Back to Recovery

Q4 2020: The slow path back to recovery Executive Summary The Spanish economy macro picture in quarter of the year show that the economy's 2021-2022: moving towards the post- gross domestic product grew at a high rate in pandemic area that period, at 16.7% q/q, in line with the most optimistic scenario by the Bank of Spain, after The Spanish economy recorded an historical the 17.8% drop in the second quarter of the contraction of the gross domestic product in year. This dynamism was generalized to all the second quarter of the year, higher than components of demand, with very large that of other neighboring countries due to five growth in private consumption, gross fixed idiosyncratic factors: a) the intensity of the capital formation and exports of goods and pandemic in Spain, which required stricter services. This expansion occurred in spite of confinement measures for the population the restrictions on international mobility that than those implemented in other countries in made the influx of tourists during the summer the immediate environment; b) the influence months very moderate. Other economies in of some structural characteristics of the our environment also registered notable Spanish economy: the high specialization in quarter-on-quarter growth. activities that require greater social interaction and particularly in the added value However, the economic recovery has been a of the commerce, transport and hospitality partial one, as evidenced by the fact that in sector, which contributes to explain 53% of the the period from July to September 2020 the decline of the economic activity observed in level of the Spanish GDP was still 9.1% lower the first three quarters of the year; c) the than at end-2019, prior to the outbreak of greater relative presence of microenterprises COVID-19, while in the economies of the euro and SMEs, which are more vulnerable to area this gap was around 4%. -

As Andalusia

THE SPANISH OF ANDALUSIA Perhaps no other dialect zone of Spain has received as much attention--from scholars and in the popular press--as Andalusia. The pronunciation of Andalusian Spanish is so unmistakable as to constitute the most widely-employed dialect stereotype in literature and popular culture. Historical linguists debate the reasons for the drastic differences between Andalusian and Castilian varieties, variously attributing the dialect differentiation to Arab/Mozarab influence, repopulation from northwestern Spain, and linguistic drift. Nearly all theories of the formation of Latin American Spanish stress the heavy Andalusian contribution, most noticeable in the phonetics of Caribbean and coastal (northwestern) South American dialects, but found in more attenuated fashion throughout the Americas. The distinctive Andalusian subculture, at once joyful and mournful, but always proud of its heritage, has done much to promote the notion of andalucismo within Spain. The most extreme position is that andaluz is a regional Ibero- Romance language, similar to Leonese, Aragonese, Galician, or Catalan. Objectively, there is little to recommend this stance, since for all intents and purposes Andalusian is a phonetic accent superimposed on a pan-Castilian grammatical base, with only the expected amount of regional lexical differences. There is not a single grammatical feature (e.g. verb cojugation, use of preposition, syntactic pattern) which separates Andalusian from Castilian. At the vernacular level, Andalusian Spanish contains most of the features of castellano vulgar. The full reality of Andalusian Spanish is, inevitably, much greater than the sum of its parts, and regardless of the indisputable genealogical ties between andaluz and castellano, Andalusian speech deserves study as one of the most striking forms of Peninsular Spanish expression. -

Northern Spain & Galicia

ESE 2108 PRICE PER PERSON IN DOUBLE OCCUPANCY NORTHERN SPAIN EUR 1.010.- Surplus single room EUR 230.- & GALICIA Surplus high season (Jul 1 – Oct 31) EUR 90.- SIB-Round trip 9 days/8 nights GROUP TOUR SET DEPARTURES 2021 Norther Spain is also known as Green Spain, a lush natural region stretching along the Atlantic coast including nearly all of Galicia, Asturias, and Cantabria, in addition to the northern parts of 04.05 11.05 18.05 the Basque Country, as well as a small portion of Navarre. It is called green because its wet and 25.05 01.06 08.06 temperate oceanic climate helps lush pastures and forests thrive, providing a landscape similar to 15.06 22.06 06.07 that of Ireland, Great Britain, and the west coast of France. The climate and landscape are 13.07 20.07 27.07 determined by the Atlantic Ocean winds whose moisture gets trapped by the mountains 03.08 10.08 17.07 circumventing the Spanish Atlantic façade. 24.08 31.08 07.09 Our trip begins in Madrid with a city tour before we head north to San Sebastian at the coast of 14.09 21.09 28.09 the Bay of Biscay, one of the most historically famous tourist destinations in Spain. Bilbao is also INCLUDED SERVICES in our plans where you will see the best architectural feature of the 1990´s, the Guggenheim • Panoramic sightseeing tours of Madrid, San Museum. This city has a significant importance in Green Spain due to its port activity, making it Sebastian, Bilbao and La Coruña the second-most industrialized region of Spain, behind Barcelona. -

Non-Figurative Cave Art in Northern Spain

THE CAVES OF CANTABRIA: NON-FIGURATIVE CAVE ART IN NORTHERN SPAIN by Dustin Riley A thesis submitted To the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfllment of the requirments for the degree of Master of Arts, Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland January, 2017 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract This project focuses on non-figurative cave art in Cantabrian (Spain) from the Upper Palaeolithic (ca. 40,000-10,000). With more than 30 decorated caves in the region, it is one of the world’s richest areas in Palaeolithic artwork. My project explores the social and cultural dimensions associated with non-figurative cave images. Non-figurative artwork accounts for any image that does not represent real world objects. My primary objectives are: (1) To produce the first detailed account of non-figurative cave art in Cantabria; (2) To examine the relationships between figurative and non-figurative images; and (3) To analyse the many cultural and symbolic meanings associated to non- figurative images. To do so, I construct a database documenting the various features of non-figurative imagery in Cantabria. The third objective will be accomplished by examining the cultural and social values of non-figurative art through the lens of cognitive archaeology. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank and express my gratitude to the members of the Department of Archaeology at Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador for giving me the opportunity to conduct research and achieve an advanced degree. In particular I would like to express my upmost appreciation to Dr. Oscar Moro Abadía, whose guidance, critiques, and continued support and confidence in me aided my development as a student and as a person.