Non-Figurative Cave Art in Northern Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Focusthe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief

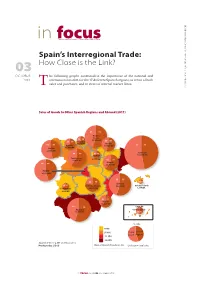

CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona in focusThe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief Spain’s Interregional Trade: 03 How Close is the Link? OCTOBER he following graphs contextualise the importance of the national and 2012 international market for the 17 dif ferent Spanish regions, in terms of both T sales and purchases, and in terms of internal market flows. Sales of Goods to Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) 46 54 Basque County 36 64 45,768 M€ 33 67 Cantabria 45 55 7,231 M€ Navarre 54 46 Asturias 17,856 M€ 53 47 Galicia 11,058 M€ 32,386 M€ 40 60 31 69 Catalonia La Rioja 104,914 M€ Castile-Leon 4,777 M€ 30,846 M€ 39 61 Aragon 54 46 23,795 M€ Madrid 45,132 M€ 45 55 22 78 5050 Valencia 29 71 Castile-La Mancha 44,405 M€ Balearic Islands Extremaura 18,692 M€ 1,694 M€ 4,896 M€ 39 61 Murcia 14,541 M€ 44 56 4,890 M€ Andalusia Canary Islands 52,199 M€ 49 51 % Sales 0-4% 5-10% To the Spanish World Regions 11-15% 16-20% Source: C-Intereg, INE and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB Share of Spanish Population (%) Circle Size = Total Sales in focus CIDOB 03 . OCTOBER 2012 CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona Purchase of Goods From Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) Basque County 28 72 36 64 35,107 M€ 35 65 Asturias Cantabria Navarre 11,580 M€ 55 45 6,918 M€ 14,914 M€ 73 27 Galicia 29 71 25,429 M€ 17 83 Catalonia Castile-Leon La Rioja 97,555 M€ 34,955 M€ 29 71 6,498 M€ Aragon 67 33 26,238 M€ Madrid 79,749 M€ 44 56 2 78 Castile-La Mancha Valencia 19 81 12 88 23,540 M€ Extremaura 49 51 45,891 M€ Balearic Islands 8,132 M€ 8,086 M€ 54 46 Murcia 18,952 M€ 56 44 Andalusia 52,482 M€ Canary Islands 35 65 13,474 M€ Purchases from 27,000 to 31,000 € 23,000 to 27,000 € Rest of Spain 19,000 to 23,000 € the world 15,000 to 19,000 € GDP per capita Circle Size = Total Purchase Source: C-Intereg, Expansión and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB 2 in focus CIDOB 03 . -

The Origin of Representational Drawing: a Comparison of Human Children and Chimpanzees

Child Development, xxxx 2014, Volume 00, Number 0, Pages 1–15 The Origin of Representational Drawing: A Comparison of Human Children and Chimpanzees Aya Saito Misato Hayashi Chubu Gakuin University Kyoto University Hideko Takeshita Tetsuro Matsuzawa The University of Shiga Prefecture Kyoto University To examine the evolutional origin of representational drawing, two experiments directly compared the draw- ing behavior of human children and chimpanzees. The first experiment observed free drawing after model presentation, using imitation task. From longitudinal observation of humans (N = 32, 11–31 months), the developmental process of drawing until the emergence of shape imitation was clarified. Adult chimpanzees showed the ability to trace a model, which was difficult for humans who had just started imitation. The sec- ond experiment, free drawing on incomplete facial stimuli, revealed the remarkable difference between two species. Humans (N = 57, 6–38 months) tend to complete the missing parts even with immature motor con- trol, whereas chimpanzees never completed the missing parts and instead marked the existing parts or traced the outlines. Cognitive characteristics may affect the emergence of representational drawings. The oldest representational drawings in existence are examining the drawing behavior of chimpanzees the upper Paleolithic cave drawings of Homo sapiens, (Pan troglodytes), humans’ closest living relatives. who drew animals with a variety of materials and Chimpanzees and humans share about 98.8% of the refined techniques (Beltran, 2000; Chauvet, Des- genome (Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis champs, & Hillaire, 1996). A recent study using Consortium, 2005) and share a common ancestor uranium-thorium dating methods estimated that that existed until about 6 Ma. -

The Janus-Faced Dilemma of Rock Art Heritage

The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon To cite this version: Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, Taylor & Francis, In press, 10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329. hal-03078965 HAL Id: hal-03078965 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03078965 Submitted on 21 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Duval Mélanie, Gauchon Christophe, 2021. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329 Authors: Mélanie Duval and Christophe Gauchon Mélanie Duval: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France; * Rock Art Research Institute GAES, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Christophe Gauchon: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France. -

5 Years on Ice Age Europe Network Celebrates – Page 5

network of heritage sites Magazine Issue 2 aPriL 2018 neanderthal rock art Latest research from spanish caves – page 6 Underground theatre British cave balances performances with conservation – page 16 Caves with ice age art get UnesCo Label germany’s swabian Jura awarded world heritage status – page 40 5 Years On ice age europe network celebrates – page 5 tewww.ice-age-europe.euLLING the STORY of iCe AGE PeoPLe in eUROPe anD eXPL ORING PLEISTOCene CULtURAL HERITAGE IntrOductIOn network of heritage sites welcome to the second edition of the ice age europe magazine! Ice Age europe Magazine – issue 2/2018 issn 25684353 after the successful launch last year we are happy to present editorial board the new issue, which is again brimming with exciting contri katrin hieke, gerdChristian weniger, nick Powe butions. the magazine showcases the many activities taking Publication editing place in research and conservation, exhibition, education and katrin hieke communication at each of the ice age europe member sites. Layout and design Brightsea Creative, exeter, Uk; in addition, we are pleased to present two special guest Beate tebartz grafik Design, Düsseldorf, germany contributions: the first by Paul Pettitt, University of Durham, cover photo gives a brief overview of a groundbreaking discovery, which fashionable little sapiens © fumane Cave proved in february 2018 that the neanderthals were the first Inside front cover photo cave artists before modern humans. the second by nuria sanz, water bird – hohle fels © urmu, director of UnesCo in Mexico and general coordi nator of the Photo: burkert ideenreich heaDs programme, reports on the new initiative for a serial transnational nomination of neanderthal sites as world heritage, for which this network laid the foundation. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Pleistocene Palaeoart of Africa

Arts 2013, 2, 6-34; doi:10.3390/arts2010006 OPEN ACCESS arts ISSN 2076-0752 www.mdpi.com/journal/arts Review Pleistocene Palaeoart of Africa Robert G. Bednarik International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (IFRAO), P.O. Box 216, Caulfield South, VIC 3162, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-95230549; Fax: +61-3-95230549 Received: 22 December 2012; in revised form: 22 January 2013 / Accepted: 23 January 2013 / Published: 8 February 2013 Abstract: This comprehensive review of all currently known Pleistocene rock art of Africa shows that the majority of sites are located in the continent’s south, but that the petroglyphs at some of them are of exceptionally great antiquity. Much the same applies to portable palaeoart of Africa. The current record is clearly one of paucity of evidence, in contrast to some other continents. Nevertheless, an initial synthesis is attempted, and some preliminary comparisons with the other continents are attempted. Certain parallels with the existing record of southern Asia are defined. Keywords: rock art; portable palaeoart; Pleistocene; figurine; bead; engraving; Africa 1. Introduction Although palaeoart of the Pleistocene occurs in at least five continents (Bednarik 1992a, 2003a) [38,49], most people tend to think of Europe first when the topic is mentioned. This is rather odd, considering that this form of evidence is significantly more common elsewhere, and very probably even older there. For instance there are far less than 10,000 motifs in the much-studied corpus of European rock art of the Ice Age, which are outnumbered by the number of publications about them. -

The Beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e21 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia * Dimas Martín-Socas a, , María Dolores Camalich Massieu a, Jose Luis Caro Herrero b, F. Javier Rodríguez-Santos c a U.D.I. de Prehistoria, Arqueología e Historia Antigua (Dpto. Geografía e Historia), Universidad de La Laguna, Campus Guajara, 38071 Tenerife, Spain b Dpto. Lenguajes y Ciencias de la Computacion, Universidad de Malaga, Complejo Tecnologico, Campus de Teatinos, 29071 Malaga, Spain c Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistoricas de Cantabria (IIIPC), Universidad de Cantabria. Edificio Interfacultativo, Avda. Los Castros, 52. 39005 Santander, Spain article info abstract Article history: The Early Neolithic in Andalusia shows great complexity in the implantation of the new socioeconomic Received 31 January 2017 structures. Both the wide geophysical diversity of this territory and the nature of the empirical evidence Received in revised form available hinder providing a general overview of when and how the Mesolithic substrate populations 6 June 2017 influenced this process of transformation, and exactly what role they played. The absolute datings Accepted 22 June 2017 available and the studies on the archaeological materials are evaluated, so as to understand the diversity Available online xxx of the different zones undergoing the neolithisation process on a regional scale. The results indicate that its development, initiated in the middle of the 6th millennium BC and consolidated between 5500 and Keywords: Iberian Peninsula 4700 cal. BC, is parallel and related to the same changes documented in North Africa and the different Andalusia areas of the Central-Western Mediterranean. -

The Aurignacian Viewed from Africa

Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University THE AURIGNACIAN VIEWED FROM AFRICA Christian A. TRYON Introduction 20 The African archeological record of 43-28 ka as a comparison 21 A - The Aurignacian has no direct equivalent in Africa 21 B - Archaic hominins persist in Africa through much of the Late Pleistocene 24 C - High modification symbolic artifacts in Africa and Eurasia 24 Conclusions 26 Acknowledgements 26 References cited 27 To cite this article Tryon C. A. , 2015 - The Aurignacian Viewed from Africa, in White R., Bourrillon R. (eds.) with the collaboration of Bon F., Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe, Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University, P@lethnology, 7, 19-33. http://www.palethnologie.org 19 P@lethnology | 2015 | 19-33 Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University THE AURIGNACIAN VIEWED FROM AFRICA Christian A. TRYON Abstract The Aurignacian technocomplex in Eurasia, dated to ~43-28 ka, has no direct archeological taxonomic equivalent in Africa during the same time interval, which may reflect differences in inter-group communication or differences in archeological definitions currently in use. Extinct hominin taxa are present in both Eurasia and Africa during this interval, but the African archeological record has played little role in discussions of the demographic expansion of Homo sapiens, unlike the Aurignacian. Sites in Eurasia and Africa by 42 ka show the earliest examples of personal ornaments that result from extensive modification of raw materials, a greater investment of time that may reflect increased their use in increasingly diverse and complex social networks. -

A B S T Ra C T S O F T H E O Ra L and Poster Presentations

Abstracts of the oral and poster presentations (in alphabetic order) see Addenda, p. 271 11th ICAZ International Conference. Paris, 23-28 August 2010 81 82 11th ICAZ International Conference. Paris, 23-28 August 2010 ABRAMS Grégory1, BONJEAN ABUHELALEH Bellal1, AL NAHAR Maysoon2, Dominique1, Di Modica Kévin1 & PATOU- BERRUTI Gabriele Luigi Francesco, MATHIS Marylène2 CANCELLIERI Emanuele1 & THUN 1, Centre de recherches de la grotte Scladina, 339D Rue Fond des Vaux, 5300 Andenne, HOHENSTEIN Ursula1 Belgique, [email protected]; [email protected] ; [email protected] 2, Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, Département Préhistoire du Muséum National d’Histoire 1, Department of Biology and Evolution, University of Ferrara, Corso Ercole I d’Este 32, Ferrara Naturelle, 1 Rue René Panhard, 75013 Paris, France, [email protected] (FE: 44100), Italy, [email protected] 2, Department of Archaeology, University of Jordan. Amman 11942 Jordan, maysnahar@gmail. com Les os brûlés de l’ensemble sédimentaire 1A de Scladina (Andenne, Belgique) : apports naturels ou restes de foyer Study of Bone artefacts and use techniques from the Neo- néandertalien ? lithic Jordanian site; Tell Abu Suwwan (PPNB-PN) L’ensemble sédimentaire 1A de la grotte Scladina, daté par 14C entre In this paper we would like to present the experimental study car- 40 et 37.000 B.P., recèle les traces d’une occupation par les Néan- ried out in order to reproduce the bone artifacts coming from the dertaliens qui contient environ 3.500 artefacts lithiques ainsi que Neolithic site Tell Abu Suwwan-Jordan. This experimental project plusieurs milliers de restes fauniques, attribués majoritairement au aims to complete the archaeozoological analysis of the bone arti- Cheval pour les herbivores. -

Art and Symbolism: the Case Of

ON THE EMERGENCE OF ART AND SYMBOLISM: THE CASE OF NEANDERTAL ‘ART’ IN NORTHERN SPAIN by Amy Chase B.A. University of Victoria, 2011 A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2017 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador ABSTRACT The idea that Neandertals possessed symbolic and artistic capabilities is highly controversial, as until recently, art creation was thought to have been exclusive to Anatomically Modern Humans. An intense academic debate surrounding Neandertal behavioural and cognitive capacities is fuelled by methodological advancements, archaeological reappraisals, and theoretical shifts. Recent re-dating of prehistoric rock art in Spain, to a time when Neandertals could have been the creators, has further fuelled this debate. This thesis aims to address the underlying causes responsible for this debate and investigate the archaeological signifiers of art and symbolism. I then examine the archaeological record of El Castillo, which contains some of the oldest known cave paintings in Europe, with the objective of establishing possible evidence for symbolic and artistic behaviour in Neandertals. The case of El Castillo is an illustrative example of some of the ideas and concepts that are currently involved in the interpretation of Neandertals’ archaeological record. As the dating of the site layer at El Castillo is problematic, and not all materials were analyzed during this study, the results of this research are rather inconclusive, although some evidence of probable symbolic behaviour in Neandertals at El Castillo is identified and discussed. -

Homo Aestheticus’

Conceptual Paper Glob J Arch & Anthropol Volume 11 Issue 3 - June 2020 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Shuchi Srivastava DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2020.11.555815 Man and Artistic Expression: Emergence of ‘Homo Aestheticus’ Shuchi Srivastava* Department of Anthropology, National Post Graduate College, University of Lucknow, India Submission: May 30, 2020; Published: June 16, 2020 *Corresponding author: Shuchi Srivastava, Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, National Post Graduate College, An Autonomous College of University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India Abstract Man is a member of animal kingdom like all other animals but his unique feature is culture. Cultural activities involve art and artistic expressions which are the earliest methods of emotional manifestation through sign. The present paper deals with the origin of the artistic expression of the man, i.e. the emergence of ‘Homo aestheticus’ and discussed various related aspects. It is basically a conceptual paper; history of art begins with humanity. In his artistic instincts and attainments, man expressed his vigour, his ability to establish a gainful and optimistictherefore, mainlyrelationship the secondary with his environmentsources of data to humanizehave been nature. used for Their the behaviorsstudy. Overall as artists findings was reveal one of that the man selection is artistic characteristics by nature suitableand the for the progress of the human species. Evidence from extensive analysis of cave art and home art suggests that humans have also been ‘Homo aestheticus’ since their origins. Keywords: Man; Art; Artistic expression; Homo aestheticus; Prehistoric art; Palaeolithic art; Cave art; Home art Introduction ‘Sahityasangeetkalavihinah, Sakshatpashuh Maybe it was the time when some African apelike creatures to 7 million years ago, the first human ancestors were appeared. -

Assessing Relationships Between Human Adaptive Responses and Ecology Via Eco-Cultural Niche Modeling William E

Assessing relationships between human adaptive responses and ecology via eco-cultural niche modeling William E. Banks To cite this version: William E. Banks. Assessing relationships between human adaptive responses and ecology via eco- cultural niche modeling. Archaeology and Prehistory. Universite Bordeaux 1, 2013. hal-01840898 HAL Id: hal-01840898 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01840898 Submitted on 11 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Thèse d'Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches Université de Bordeaux 1 William E. BANKS UMR 5199 PACEA – De la Préhistoire à l'Actuel : Culture, Environnement et Anthropologie Assessing Relationships between Human Adaptive Responses and Ecology via Eco-Cultural Niche Modeling Soutenue le 14 novembre 2013 devant un jury composé de: Michel CRUCIFIX, Chargé de Cours à l'Université catholique de Louvain, Belgique Francesco D'ERRICO, Directeur de Recherche au CRNS, Talence Jacques JAUBERT, Professeur à l'Université de Bordeaux 1, Talence Rémy PETIT, Directeur de Recherche à l'INRA, Cestas Pierre SEPULCHRE, Chargé de Recherche au CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette Jean-Denis VIGNE, Directeur de Recherche au CNRS, Paris Table of Contents Summary of Past Research Introduction ..................................................................................................................