Linguistic Strata in Ancient Cantabria: the Evidence of Toponyms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

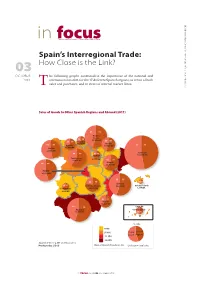

In Focusthe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief

CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona in focusThe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief Spain’s Interregional Trade: 03 How Close is the Link? OCTOBER he following graphs contextualise the importance of the national and 2012 international market for the 17 dif ferent Spanish regions, in terms of both T sales and purchases, and in terms of internal market flows. Sales of Goods to Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) 46 54 Basque County 36 64 45,768 M€ 33 67 Cantabria 45 55 7,231 M€ Navarre 54 46 Asturias 17,856 M€ 53 47 Galicia 11,058 M€ 32,386 M€ 40 60 31 69 Catalonia La Rioja 104,914 M€ Castile-Leon 4,777 M€ 30,846 M€ 39 61 Aragon 54 46 23,795 M€ Madrid 45,132 M€ 45 55 22 78 5050 Valencia 29 71 Castile-La Mancha 44,405 M€ Balearic Islands Extremaura 18,692 M€ 1,694 M€ 4,896 M€ 39 61 Murcia 14,541 M€ 44 56 4,890 M€ Andalusia Canary Islands 52,199 M€ 49 51 % Sales 0-4% 5-10% To the Spanish World Regions 11-15% 16-20% Source: C-Intereg, INE and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB Share of Spanish Population (%) Circle Size = Total Sales in focus CIDOB 03 . OCTOBER 2012 CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona Purchase of Goods From Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) Basque County 28 72 36 64 35,107 M€ 35 65 Asturias Cantabria Navarre 11,580 M€ 55 45 6,918 M€ 14,914 M€ 73 27 Galicia 29 71 25,429 M€ 17 83 Catalonia Castile-Leon La Rioja 97,555 M€ 34,955 M€ 29 71 6,498 M€ Aragon 67 33 26,238 M€ Madrid 79,749 M€ 44 56 2 78 Castile-La Mancha Valencia 19 81 12 88 23,540 M€ Extremaura 49 51 45,891 M€ Balearic Islands 8,132 M€ 8,086 M€ 54 46 Murcia 18,952 M€ 56 44 Andalusia 52,482 M€ Canary Islands 35 65 13,474 M€ Purchases from 27,000 to 31,000 € 23,000 to 27,000 € Rest of Spain 19,000 to 23,000 € the world 15,000 to 19,000 € GDP per capita Circle Size = Total Purchase Source: C-Intereg, Expansión and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB 2 in focus CIDOB 03 . -

Los Celtas Y El País Vasco

P. BOSCH GIMPERA Si hay hoy un punto firme en la etnología peninsular parece ser el carácter no ibérico ni céltico de los grupos vascos, ‘así como su origen en los pueblos de la cultura pirenaica del eneolítico. Sobre ello hemos tratado en otras ocasiones y no es preciso repetir lo dicho entonces. Recientemente se han publicado un trabajo del Sr. Sánchez Albornoz: Divisiones tribales y administrativas del solar del reino de Asturias en la época romana (Madrid 1929) y otro nuestro: Etno- logía de la península ibérica (Barcelona 1932), en los cuales se ofre- cen nuevos puntos de vista interesantes para el problema de la etno- logía vasca y para su historia primitiva. El Sr. Sánchez Albornoz obtiene una delimitación muy precisa y exacta en la mayor parte de sus puntos de las tribus del N. de España, incluyendo en ellas a los pueblos vascos. En nuestro libro, tratando más ampliamente los problemas que habíamos venido estudiando en diferentes estu- dios anteriores creemos poder rectificar algunos detalles de la deli- mitación del Sr. Sánchez Albornoz y sobre todo llegar a conclu- siones de interés acerca de los movimientos célticos en España que pueden cambiar la manera de verlos en relación con el país vasco. Por ello conviene, resumiendo lo dicho en nuestra obra acerca de la delimitación de las tribus vascas, tratar más ampliamente del problema de los celtas en relación con ellas. El territorio de los pueblos vascos Los vascones ocupan aproximadamente el territorio de la actual Navarra, salen al mar por el extremo oriental de Guipúzcoa y son vecinos, por su parte SE. -

Los Nombres Personales De Los Autrigones. Contribución Al Estudio De La Etnicidad De Los Pueblos Prerromanos Del Norte De Hispania (II)

Los nombres personales de los Autrigones. Contribución al estudio de la etnicidad de los pueblos prerromanos del Norte de Hispania (II) Personal names of the Autrigones. Contribution to the study of the ethnicity of the pre-roman peoples of northern Hispania (II) BRUNO CARCEDO DE ANDRÉS Universidad de Burgos [email protected] Recibido: 1-7-2017. Aceptado: 4-12-2017 . Cómo citar: Carcedo de Andrés, Bruno, “TLos nombres personales de los Autrigones. Contribución al estudio de la etnicidad de los pueblos prerromanos del Norte de Hispania (II)”, Hispania Antiqva. Revista de Historia Antigua XLI (2017): 20-40. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24197/ha.XLI.2017.20-40 Resumen: El presente trabajo trata de estudiar el estrato antroponímico de los testimonios de los Autrigones, aportando algunos datos más para intentar conocer el origen étnico y cultural de este pueblo prerromano. Palabras clave: Antroponimia; Epigrafía; Etnicidad; Indoeuropeo; Celtibérico; Galo. Abstract: This work is aimed to study the anthroponymic stratum of the testimonials of the Autrigones, providing some more data in order to understand the ethnic and cultural background of these pre-Roman people. Keywords: Anthroponymy; Epigraphy; Ethnicity; Indoeuroepan; Celtiberian language; Gaulish. Sumario: Introducción; 22. ET-; 23. LAC-?/IAC-?; 24. LAT(T)-; 25. LEC-/LIC-; 26. LOUK-/LUK-; 27. MAGL-; 28. MURC-; 29. PED-/PET-; 30. PLAND-; 31. REB-; 32. SAND-; 33. SEC-/SEG-; 34. SUR-; 35. TAUR-; 36. TON(N)-; 37. TRIT-; 38. TUR-; 39. VIC-/VIG-; Conclusiones. Summary: Introduction; 22. ET-; 23. LAC-?/IAC-?; 24. LAT(T)-; 25. LEC-/LIC-; 26. LOUK-/LUK-; 27. MAGL-; 28. MURC-; 29. PED-/PET-; 30. -

Exam Sample Question

Latin II St. Charles Preparatory School Sample Second Semester Examination Questions PART I Background and History (Questions 1-35) Directions: On the answer sheet cover the letter of the response which correctly completes each statement about Caesar or his armies. 1. The commander-in-chief of a Roman army who had won a significant victory was known as a. dux b. imperator c. signifer d. sagittarius e. legatus 2. Caesar was consul for the first time in the year a. 65 B.C. b. 70 B.C. c. 59 B.C. d. 44 B.C. e. 51 B.C. PART II Vocabulary (Questions 36-85) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the correct meaning for the boldfaced Latin word in the left band column. 36. doctus a. edge b. entrance c. learned d. record e. friendly 37. incipio a. stop b. speaker c. rest d. happen e. begin PART III Prepared Translation, Passage A (Questions 86-95) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the best translation for each Latin sentence or fragment. 86. Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres. a. The Gauls divided themselves into three parts b. All of Gaul was divided into three parts c. Three parts of Gaul have been divided d. Everyone in Gaul was divided into three parts PART IV Prepared Translation, Passage B (Questions 96-105) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the best translation for each Latin sentence or fragment. 96. Galli se Celtas appellant. Romani autem eos Gallos appellant. -

Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-16-2016 12:00 AM Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain Robert Jackson Woodcock The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Alexander Meyer The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Classics A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Robert Jackson Woodcock 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Indo- European Linguistics and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Woodcock, Robert Jackson, "Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3775. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3775 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Language is one of the most significant aspects of cultural identity. This thesis examines the evidence of languages in contact in Roman Britain in order to determine the role that language played in defining the identities of the inhabitants of this Roman province. All forms of documentary evidence from monumental stone epigraphy to ownership marks scratched onto pottery are analyzed for indications of bilingualism and language contact in Roman Britain. The language and subject matter of the Vindolanda writing tablets from a Roman army fort on the northern frontier are analyzed for indications of bilingual interactions between Roman soldiers and their native surroundings, as well as Celtic interference on the Latin that was written and spoken by the Roman army. -

Disrupting the Party: a Case Study of Ahora Madrid and Its Participatory Innovations

Disrupting the Party: A Case Study of Ahora Madrid and Its Participatory Innovations Quinton Mayne and Cecilia Nicolini September 2020 Disrupting the Party: A Case Study of Ahora Madrid and Its Participatory Innovations Quinton Mayne and Cecilia Nicolini September 2020 disrupting the party: A Case Study of Ahora Madrid and Its Participatory Innovations letter from the editor The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excel- lence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing powerful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Ash Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. Our Occasional Papers Series highlights new research and commentary that we hope will engage our readers and prompt an energetic exchange of ideas in the public policy community. This paper is contributed by Quinton Mayne, Ford Foundation Associate Profes- sor of Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School and an Ash Center faculty associate, and Cecilia Nicolini, a former Ash Center Research Fellow and a current advisor to the president of Argentina. The paper addresses issues that lie at the heart of the work of the Ash Center—urban governance, democratic deepening, participatory innova- tions, and civic technology. It does this through a study of the fascinating rise of Ahora Madrid, a progressive electoral alliance that—to the surprise of onlookers—managed to gain political control, just a few months after being formed, of the Spanish capital following the 2015 municipal elections. Headed by the unassuming figure of Manuela Carmena, a former judge, Ahora Madrid won voters over with a bold agenda that reimagined the relationship between citizens and city hall. -

Celts and the Castro Culture in the Iberian Peninsula – Issues of National Identity and Proto-Celtic Substratum

Brathair 18 (1), 2018 ISSN 1519-9053 Celts and the Castro Culture in the Iberian Peninsula – issues of national identity and Proto-Celtic substratum Silvana Trombetta1 Laboratory of Provincial Roman Archeology (MAE/USP) [email protected] Received: 03/29/2018 Approved: 04/30/2018 Abstract : The object of this article is to discuss the presence of the Castro Culture and of Celtic people on the Iberian Peninsula. Currently there are two sides to this debate. On one hand, some consider the “Castro” people as one of the Celtic groups that inhabited this part of Europe, and see their peculiarity as a historically designed trait due to issues of national identity. On the other hand, there are archeologists who – despite not ignoring entirely the usage of the Castro culture for the affirmation of national identity during the nineteenth century (particularly in Portugal) – saw distinctive characteristics in the Northwest of Portugal and Spain which go beyond the use of the past for political reasons. We will examine these questions aiming to decide if there is a common Proto-Celtic substrate, and possible singularities in the Castro Culture. Keywords : Celts, Castro Culture, national identity, Proto-Celtic substrate http://ppg.revistas.uema.br/index.php/brathair 39 Brathair 18 (1), 2018 ISSN 1519-9053 There is marked controversy in the use of the term Celt and the matter of the presence of these people in Europe, especially in Spain. This controversy involves nationalism, debates on the possible existence of invading hordes (populations that would bring with them elements of the Urnfield, Hallstatt, and La Tène cultures), and the possible presence of a Proto-Celtic cultural substrate common to several areas of the Old Continent. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Analysis of a Celtiberian Protective Paste and Its Possible Use by Arevaci Warriors Jesús Martín-Gil

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 5 Warfare Article 3 3-13-2007 Analysis of a Celtiberian protective paste and its possible use by Arevaci warriors Jesús Martín-Gil Gonzalo Palacios-Leblé Pablo Matin Ramos Francisco J. Martín-Gil Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Part of the Celtic Studies Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Folklore Commons, History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Linguistics Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Martín-Gil, Jesús; Palacios-Leblé, Gonzalo; Ramos, Pablo Matin; and Martín-Gil, Francisco J. (2007) "Analysis of a Celtiberian protective paste and its possible use by Arevaci warriors," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 5 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol5/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Analysis of a Celtiberian protective paste and its possible use by Arevaci warriors Jesús Martín-Gil*, Gonzalo Palacios-Leblé, Pablo Martín Ramos and Francisco J. Martín-Gil Abstract This article presents an infrared spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction analysis of residue adhering to a Celtiberian pottery sherd of late Iron Age date from the Arevacian site of Cerro del Castillo, in Ayllón (Segovia, Spain). This residue may be a paste used since antiquity for protective aims. Orange-sepia in colour, made from crushed bones and glue, the paste was used by Greeks and Romans and later in the construction of the cathedrals and monasteries of Europe to confer a warm colour to the stone and to protect it against environmental deterioration. -

Bocyl N.º 12, 17 De Enero De 2018

Boletín Oficial de Castilla y León Núm. 12 Miércoles, 17 de enero de 2018 Pág. 1455 I. COMUNIDAD DE CASTILLA Y LEÓN D. OTRAS DISPOSICIONES CONSEJERÍA DE ECONOMÍA Y HACIENDA ORDEN EYH/1196/2017, de 26 de diciembre, por la que se aprueba el Programa Territorial de Fomento para Miranda de Ebro 2017-2019. La Ley 6/2014, de 12 de septiembre, de Industria de Castilla y León, en su artículo 28, apartado 4, establece que «Cuando concurran especiales necesidades de reindustrialización o se trate de zonas en declive, el Plan Director de Promoción Industrial de Castilla y León podrá prever programas territoriales de fomento, referidos a uno o varios territorios determinados de la Comunidad. Serán aprobados por la Consejería con competencias en materia de industria, previa consulta de aquellas otras Consejerías que tengan competencias en sectores o ramas concretos de la actividad industrial». El Plan Director de Promoción Industrial de Castilla y León 2017-2010, aprobado por Acuerdo 26/2017, de 8 de junio, de la Junta de Castilla y León, contempla la existencia de Programas Territoriales de Fomento, referidos a uno o varios territorios determinados de la Comunidad, cuando concurran especiales necesidades de reindustrialización o se trate de zonas en declive. En el citado Plan se establece que se podrá contemplar la existencia de Programas Territoriales de Fomento cuando tenga lugar alguna de las circunstancias siguientes: 1) Que se produzcan procesos de deslocalización continua que afecten a una o varias industrias y que impliquen el cese o despido de cómo mínimo 500 trabajadores durante un período de referencia de 18 meses en una población o en una zona geográfica determinada de Castilla y León. -

MGC Menu 2 0.Pdf

Appetizers Main Dishes Enchiladas Chips & Salsa $4.25 Tacos Our enchiladas are served flat with jack cheese and Fresh tomatillo salsa and a roasted tomato arbol chile Our tacos are served with rice, refried black beans, and topped with New Mexico green chile. Served with rice, salsa. Served with chips. garnished with pico de gallo and lettuce. Each order has refry black beans, and sour cream. Garnished with three soft corn tortillas. Served with a side of salsa de lettuce and pico de gallo. Guacamole & Chips $10.50 chile arbol. Our homemade guacamole and chips. Jack Cheese only $12.75 Grilled veggies $13.75 Salsas & Guacamole $12.50 Grilled veggies $13.75 Shredded chicken $13.75 Our homemade salsas and guacamole with a basket of Shredded pork with chipotle chile, Grilled shrimp with mushrooms and onions $15.75 chips. onions, and garnished with cilantro $14.75 Grilled steak with mushrooms and onions $15.75 Grilled chicken breast $15.75 Taquitos $13.75 Grilled sirloin steak $15.75 House Specialties Five fried taquitos made with our creamed chicken on Grilled shrimp and mushrooms topped with Flautas $14.75 corn tortillas. Served with arbol chile salsa and guacamole $15.75 Three fried chicken flautas stuffed with cheese, cilantro, guacamole. and onions. Served with rice, refry black beans, sour cream, guacamole, and a side of arbol chile salsa. Quesadillas Burritos A grilled flour tortilla filled with melted jack cheese and Our burritos are served with rice, refried black beans, Chimichangas $14.75 chipotle mayonnaise. Served with sour cream, sour cream, and garnished with pico de gallo and Three fried chimichangas with creamed chicken.