A Graduate Vocal Performance Recital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food of Love Folio Manhattan

Join us for Cerddorion’s 20th Anniversary Season! Our twentieth season launches Friday, November 14 at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Carroll ERDDORION Gardens, Brooklyn. Our Manhattan concert date will be finalized soon. In March 2015, we will mark our 20th anniversary with a special concert, including the winners VOCAL ENSEMBLE of our third Emerging Composers Competition. The season will conclude with our third concert C late in the spring. Be sure to check www.Cerddorion.org for up-to-date information, and keep an eye out for James John word of our special anniversary gala in the spring! Artistic Director !!! P RESENTS Support Cerddorion Ticket sales cover only a small portion of our ongoing musical and administrative expenses. If you would like to make a tax-deductible contribution, please send a check (payable to Cerddorion NYC, Inc.) to: The Food of Love Cerddorion NYC, Inc. Post Office Box 946, Village Station HAKESPEARE IN SONG New York, NY 10014-0946 S I N C OLLABORATION WITH !!! HE HAKESPEARE OCIETY For further information about Cerddorion Vocal Ensemble, please visit our web site: T S S Michael Sexton, Artistic Director WWW.CERDDORION.ORG Join our mailing list! !!! or Follow us on Twitter: @cerddorionnyc Sunday, June 1 at 3pm Sunday, June 8 at 3pm or St. Paul’s Episcopal Church St. Ignatius of Antioch Like us on Facebook 199 Carroll Street, Brooklyn 87th Street & West End Avenue, Manhattan THE PROGRAM DONORS Our concerts would not be possible without a great deal of financial assistance. Cerddorion would like to Readings presented by Anne Bates and Chukwudi Iwuji, courtesy of The Shakespeare Society thank the following, who have generously provided financial support for our activities over the past year. -

THE PROBLEM of GENERATIONS As to Be Capable of Choosing Rationally the Form of Government Most Suitable for Himself

HOW THE PROBLEM STANDS AT THE MOMENT 277 forms of historical being. But if the ultimate human relationships are changed, the existence of man as we have come to understand it must cease altogether-culture, creativeness, tradition must all disappear, or must at least appear in a totally different light. Hume actually experimented with the idea of a modification of such ultimate data. Suppose, he said, the type of succession of human generations to be completely altered to resemble that of CHAPTER VII a butterfly or caterpillar, so that the older generation disappears at one stroke and the new one is born all at once. Further, suppose man to be of such a high degree of mental development THE PROBLEM OF GENERATIONS as to be capable of choosing rationally the form of government most suitable for himself. (This, of course, was the main problem I. HOW THE PROBLEM STANDS AT THE MOMENT of Hume's time.) These conditions given, he said, it would be both possible and proper for each generation, without reference A. THE POSITIVIST FORMULATION OF THE PROBLEM to the ways of its ancestors, to choose afresh its own particular form of state. Only because mankind is as it is-generation follow• of investigation into his problem. All too often it falls to ing generation in a continuous stream, so that whenever one THEhis lotfirsttotaskdealofwiththe sociologiststray problemsis to toreviewwhichtheallgeneralthe sciencesstate person dies off, another is b-9rn to replace him-do we find it in turn have made their individual contribution without anyone necessary to preserve the continuity of our forms of government. -

Download PDF Booklet

T HE COMPLETE volume 2 S ONGBOOK M ARK STONE M ARK STONE S TEPHEN BAS TRELPOHEW N BARLOW THE COMPLETE SONGBOOK volume 2 ROGER QUILTER (1877-1953) FIVE JACOBEAN LYRICS Op.28 1 i The jealous lover (John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester) 2’34 2 ii Why so pale and wan? (Sir John Suckling) 1’05 3 iii I dare not ask a kiss (Robert Herrick) 1’17 4 iv To Althea, from prison (Richard Lovelace) 2’04 5 v The constant lover (Sir John Suckling) 1’56 TWO SONGS , 1903 (Roger Quilter) 6 i Come back! 1’36 7 ii A secret 1’08 8 FAIRY LULLABY (Roger Quilter) 2’43 THREE SONGS OF WILLIAM BLAKE Op.20 (William Blake) 9 i Dream valley 2’27 10 ii The wild flower’s song 2’14 11 iii Daybreak 1’59 12 ISLAND OF DREAMS (Roger Quilter) 3’14 13 AT CLOSE OF DAY (Laurence Binyon) 2’39 14 THE ANSWER (Laurence Binyon) 1’52 FIVE ENGLISH LOVE LYRICS Op.24 15 i There be none of beauty’s daughters (George Gordon Lord Byron) 2’10 16 ii Morning song (Thomas Heywood) 2’07 17 iii Go, lovely rose (Edmund Waller) 3’11 18 iv O, the month of May (Thomas Dekker) 1’55 19 v The time of roses (Thomas Hood) 2’03 20 MY HEART ADORNED WITH THEE (Roger Quilter) 1’47 THHREEREE S SONGSONGS F FOROR B BARITONEARITONE O ORR T TENORENOR OOp.18p.18 NNo.1-3o.1-3 2211 ii TToo wwineine aandnd bbeautyeauty ((JohnJohn WWilmot,ilmot, EEarlarl ooff RRochester)ochester) 11’49’49 2222 iiii WWherehere bbee yyouou ggoing?oing? ((JohnJohn KKeats)eats) 11’34’34 2233 iiiiii TThehe jjocundocund ddanceance ((WilliamWilliam BBlake)lake) 11’55’55 2244 APPRILRIL L LOVEOVE ((RogerRoger QQuilter)uilter) 11’60’60 -

Family Tree Maker

Ancestors of Mary Ruth Wilson Parents Grandparents Gr-Grandparents 2nd Gr-Grandparents 3rd Gr-Grandparents 4th Gr-Grandparents 5th Gr-Grandparents 6th Gr-Grandparents 7th Gr-Grandparents 8th Gr-Grandparents 9th Gr-Grandparents 10th Gr-Grandparents George Wilson b: 1729 in Tyrone County, Ireland m: 1749 in Staunton, Augusta County, VA d: Feb 1777 in Quibbletown, New Jersey John Wilson b: 1753 in Staunton, VA m: 25 Oct 1775 d: 23 Sep 1799 in Mason County, Kentucky Elizabeth McCreary George Wilson b: 28 Dec 1778 m: 05 Oct 1798 in Mason County, Kentucky d: 1828 in Lewis County, Kentucky John Swearingen b: Dec 1721 in Prince Georges, MD m: 15 Sep 1748 in Frederick, MD d: 13 Aug 1784 in Concord, Fayette Co., PA Drusilla Swearingen b: 07 Nov 1758 in Frederick, MD d: 1826 in Maysville, Mason Co., KY John Stull Cary Wilson b: 03 Nov 1812 in Adams County, OH m: 08 Dec 1836 in Lewis County, KY d: 01 Apr 1883 in Lafayette, IL Catherine Stull b: Abt. 1731 in Hagerstown, MD d: Abt. 1830 in Springhill Twp., Fayette, PA Martha ? Hugh Evans d: 1807 in Highland County, Ohio Sophia Evans b: 1784 in Pennsylvania d: 1851 in Lewis County, Kentucky George Thomas Wilson b: 14 Sep 1837 in Lewis County, KY m: 17 Jul 1867 in Lafayette, IN Levina Simpson d: 1902 in Des Moines, IA - Source, Greta Brown Thomas Thompson b: in Kentucky Abigail Thompson b: 08 Jan 1815 in KY d: 13 Oct 1859 in Lewis County, KY Charles Edward Wilson b: 12 Oct 1878 in Putnam County, Illinois Mary m: 02 May 1901 in Des Moines, IA d: 08 Oct 1953 in Clear Lake, IA John Longley b: 13 Jun 1782 in New York, New York d: 26 Nov 1867 in Indiana Ella Longley b: 10 Jun 1838 in Yorktown, IN d: 01 Jun 1912 in Des Moines, IA Thomas Wayne Wilson b: 20 Sep 1907 in Des Emily Huntington Moines, Polk, Iowa m: 20 Sep 1930 in Des Moines, IA d: 26 Jun 1972 in Cincinnati, Hamilton, OH Thomas Harry Hawthorne b: Abt. -

Much to Look Forward To

Journal of the No.18 June 2000 EDITOR Stephen Connock RVW (see address below) Society In this issue... Much to look forward to... Vaughan Williams and Bach The RVW Society is involved in a Members will also be delighted to learn number of important and exciting that Sir John in Love will be performed G R.V.W. & J.S.B. projects, some of which will come to in Newcastle City Hall by the Northern fruition quickly and others will take Sinfonia under Richard Hickox on by Michael Kennedy place in the 2002-2003 season. Of the September 29th 2000 as part of the Page 4 greatest interest to RVW Society preparation for the recording. There is members is the major Festival of such marvellous, heart warming music symphonies and choral works being in this opera that all members are urged G Lewis Foreman reviews VW planned under the title Toward the to get to Newcastle, somehow, for the conducting the St. Matthew Unknown Region. concert performance on 29th September. Passion. Page 7 Toward the Unknown Region Charterhouse Symposium G This Festival will be conducted by Following the success of the Conference VW and ‘the greatest of all Richard Hickox using his new orchestra Vaughan Williams in a New Century at composers’ the BBC National Orchestra of Wales. the British Library last November, Robin by Timothy Day Eight concerts are being planned for Wells of Charterhouse and Byron Adams Wales and there are likely to be four of the University of California have Page 10 concerts in London. The Festival begins jointly planned a superb series of at the end of 2002 and many rare choral lectures, concerts and other events at works will be programmed alongside all Charterhouse School from 23rd to 29th Postscripts on George the nine symphonies. -

Roger Quilter

ROGER QUILTER 1877-1953 HIS LIFE, TIMES AND MUSIC by VALERIE GAIL LANGFIELD A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham February 2004 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Roger Quilter is best known for his elegant and refined songs, which are rooted in late Victorian parlour-song, and are staples of the English artsong repertoire. This thesis has two aims: to explore his output beyond the canon of about twenty-five songs which overshadows the rest of his work; and to counter an often disparaging view of his music, arising from his refusal to work in large-scale forms, the polished assurance of his work, and his education other than in an English musical establishment. These aims are achieved by presenting biographical material, which places him in his social and musical context as a wealthy, upper-class, Edwardian gentleman composer, followed by an examination of his music. Various aspects of his solo and partsong œuvre are considered; his incidental music for the play Where the Rainbow Ends and its contribution to the play’s West End success are examined fully; a chapter on his light opera sheds light on his collaborative working practices, and traces the development of the several versions of the work; and his piano, instrumental and orchestral works are discussed within their function as light music. -

St. Cecilia Chamber Choir's Lively Performance Celebrates Spring Review

Wednesday, May 02, 2012 St. Cecilia Chamber Choir's Lively Performance Celebrates Spring Review By Kim Fletcher Wednesday, May 02, 2012 It was a perfect day when the St. Cecilia Chamber Choir joined their beautiful voices together to "Celebrate Spring" in their second performance of the weekend at the First Congregational Church in Camden April 29. Lincoln County concertgoers enjoyed their first program at the Second Congregational Church in Newcastle April 28. Directed by Linda Blanchard with Sean Fleming on the church's outstanding organ and piano, the performance was stirring and had some surprises, too. Kudos goes to Blanchard in her never failing to please selections - wonderful to hear and challenging to sing. She also gives hands-up to rising artists, particularly locals when she offers a place in the alto section to a young vocalist, this time to Lincoln Academy 2011 graduate, Olivia DeLisle. She also seeks out local talented composers, most notably and most often Richard Francis and for this concert, an absolutely beautiful piece by Todd Monsell, set to the poetry of Robert Frost. Francis' lovely contribution, "For Winter's Ruins and Rains Are Over" came back-to-back with Monsell's "A Prayer in Spring," and were stirring highlights of the first act, (aside from a personal favorite, "Jerusalem" by C. Hubert Parry, arranged by Maurice Jacobson). Blanchard also deserves a particular nod for presenting seldom-heard works, "Three Shakespeare Songs," by Vaughan Williams, and "Shakespeare Songs, Book III," featuring a solo by DeLisle, by composer Matthew Harris. Arguably the supreme poet, Shakespeare's verse and sonnets have inspired many composers most often for solo singers, which makes Williams' beautiful offerings for choirs particularly wonderful. -

Of Tif^ Twenty-Fourth Rehearsal and Concert

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES : : : Telephone, 1492 Back Bay TWENTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1906-1907 DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor prngmmm? of tif^ Twenty-fourth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, MAY 3 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, MAY 4 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 1813 " PIANOS "Without HAROLD BAUER exception the finest piano I have ever met with." " I have never before been so completely satisfied with any OSSIP GABRILOWITSCH piano as with the Mason & Hamlin." "Mason & Hamlin pianos WILLY HESS are matchless." "An artistic creation which KATHARINE GOODSON need fear no rival." " Unsurpassed by any Ameri- GEORGE CHADWICK can orEuropean instruments. "One can sing expressively VINCENT D'INDY on your piano." "Great beauty of tone and CH. M. LOEFFLER unusual capacity for expres- siveness." " I congratulate you on the ANTOINETTE SZUNOWSKA perfection of your instru- ments." "Musical instrument of the FRANZ KNEISEL highest artistic stamp." " I believe the Mason & Ham- RUDOLPH GANZ lin piano matchless, an artis- tic ideal." " I congratulate you on these HEINRICH GEBHARD wonderful instruments." EMIL PAUR " Superb, ideal." " Unequalled in beauty of TIMOTHEE ADAMOWSKI tone, singing capacity, and perfection of mechanism." "Pre-eminently sympathetic to WALLACE GOODRICH the player in both touch and tone." MASON & HAMLIN CO. 492-494 Boylston Street Opposite Institute of Technology 1814 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1906-1907 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Willy Hess, C»ncertmeitter, and the Members of the Orchestra in alphabetical order. Adamowski, J. Heberlein, H. Adamo^rski, T. -

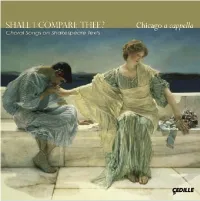

085-Shall-I-Compare-Thee-Booklet.Pdf

1 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Producer James Ginsburg Engineer Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, Bill Maylone Session Director Patrick Sinozich And summer’s lease hath all too short a date. Recorded November 13, 2004; and January 14–16 CDR 90000 085 and March 19, 2005 at Northeastern Illinois University P&C 2005 Cedille Records,24 trademark of Graphic Design The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation Melanie Germond & Pete Goldlust DDD • All Rights Reserved Front cover CEDILLE RECORDS Ask me no more, 1906 (oil on canvas) 5255 N. Lakewood Ave Chicago IL 60640 USA by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema 773.989.2515 • [email protected] © The Bridgeman Art Library www.cedillerecords.org S Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are supported in part by contributions and grants from individuals, foundations, corporations, and government agencies including the Alphawood Foundation, the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs (CityArts III Grant), and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. 2 3 SHALL I COMPARE THEE? Chicago a cappella Choral Songs on Shakespeare Texts Amy Conn, soprano Kathleen Dietz, soprano John Rutter (b. 1945) Elizabeth Grizzell, mezzo bl It Was a Lover and his Lass (2:28) Susan Schober, mezzo Harold Brock, tenor Nils Lindberg (b. 1933) bm Trevor Mitchell, tenor Shall I compare? (2:26) Matthew Greenberg, baritone Aaron Johnson, baritone Håkan Parkman (1955–1988): from Three Shakespeare Songs bn Jonathan Miller, bass Madrigal (Take, O Take Those Lips Away) (1:37) & artistic direction (ensemble: Conn, Dietz, Grizzell, Mitchell, Miller) bo Sonnet 147 (My love is as a fever) (3:03) The participation of the artists in this recording (solo: Amy Conn / ensemble: Dietz, Grizzell, Mitchell, Miller) was underwritten in part through the generosity of the Nora Bergman Fund. -

Historic Preservation Commission Agenda

HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION AGENDA Wildwood City Hall – Community Room 16860 Main Street - Wildwood, Missouri Thursday, June 28, 2018 – 7:00 p.m. I. Welcome And Roll Call II. Opening Remarks By Chair Wojciechowski III. Approval Of The Historic Preservation Commission May 24, 2018 Meeting Minutes Documents: III. DRAFT HPC MTG MINUTES_5-24-18.PDF IV. New Business a. Ready For Action – Four (4) Items 1. Action On A Demolition Request Of A Commercial Structure And A Residential Dwelling Located Upon The Property At 18130 Manchester Road (Locator Number 24X240081). Zoning Authorization For Demolition Of The 3,150 Square-Foot Commercial Structure (Formerly Schott’s Pontiac Sales And Garage) And The Bungalow, Received By The Department On 5/24/2018, Is Pending Utility-Disconnect Letters. Date Of Construction Of The Building Is Stated As 1921, According To St. Louis County Department Of Revenue – Assessor’s Office Records, Requiring The Commission’s Review, Given The Dwelling Is In Excess Of 75 Years Of Age. (Ward Six) Documents: IV.A.1. DEMOLITION REQUEST_18130 MANCHESTER ROAD SITE VISIT NOTES.PDF 2. Update On 2018 Work Program Of The Historic Preservation Commission Documents: IV.A.2. WORK PROGRAM UPDATE FOR JUNE 28, 2018 MEETING.PDF 3. Discussion On Display Boards For Presentations And Special Events (Wards – All) Documents: IV.A.3. DRAFTS OF DISPLAY BOARDS.PDF 4. Review Of Final Draft Of Next Chapter In Wildwood Written History For Celebrate Wildwood Booklet (Wards – All) Documents: IV.A.4. FINAL DRAFT OF NEXT CHAPTER IN WILDWOOD WRITTEN HISTORY - 1860-1919.PDF b. Not Ready For Action – No Items V. -

Eldon Black Sheet Music Collection This Sheet Music Is Only Available for Use by ASU Students, Faculty, and Staff

Eldon Black Sheet Music Collection This sheet music is only available for use by ASU students, faculty, and staff. Ask at the Circulation Desk for assistance. (Use the Adobe "Find" feature to locate score(s) and/or composer(s).) Call # Composition Composer Publisher Date Words/Lyrics/Poem/Movie Voice & Instrument Range OCLC 000001a Allah's Holiday Friml, Rudolf G. Schirmer, Inc. 1943 From "Katinka" a Musical Play - As Presented by Voice and Piano Original in E Mr. Arthur Hammerstein. Vocal Score and Lyrics 000001b Allah's Holiday Friml, Rudolf G. Schirmer, Inc. 1943 From "Katinka" a Musical Play - As Presented by Voice and Piano Transposed in F Mr. Arthur Hammerstein. Vocal Score and Lyrics by Otto A. Harbach 000002a American Lullaby Rich, Gladys G. Schirmer, Inc. 1932 Voice and Piano Low 000002b American Lullaby Rich, Gladys G. Schirmer, Inc. 1932 Voice and Piano Low 000003a As Time Goes By Hupfel, Hupfeld Harms, Inc. 1931 From the Warner Bros. Picture "Casablanca" Voice and Piano 000003b As Time Goes By Hupfel, Hupfeld Harms, Inc. 1931 From the Warner Bros. Picture "Casablanca" Voice and Piano 000004a Ah, Moon of My Delight - In A Persian Garden Lehmann, Liza Boston Music Co. 1912 To words from the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" Voice and Piano Medium, F 000004b Ah, Moon of My Delight - In A Persian Garden Lehmann, Liza Boston Music Co. 1912 To words from the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" Voice and Piano Medium, F 000004c Ah, Moon of My Delight - In A Persian Garden Lehmann, Liza Boston Music Co. 1912 To words from the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" Voice and Piano Medium, F 000005 Acrostic Song Tredici, David Del Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. -

Delius Journal 133.Qxd 28/12/2007 12:53 Page 1

Delius Journal 133 Cover.qxd 28/12/2007 12:56 Page 1 The Delius Society JOURNAL Spring 2003 Number 133 Delius Journal 133.qxd 28/12/2007 12:53 Page 1 The Delius Society Journal Spring 2003, Number 133 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No. 298662) Full Membership and Institutions £20 per year UK students £10 per year USA and Canada US$38 per year Africa, Australasia and Far East £23 per year President Felix Aprahamian Vice Presidents Lionel Carley BA, PhD Meredith Davies CBE MA BMus FRCM Sir Andrew Davis CBE Vernon Handley MA, FRCM Richard Hickox FRCO Lyndon Jenkins Richard Kitching Tasmin Little FGSM ARCM (Hons) Hon D.Litt DipGSM David Lloyd-Jones BA FGSM HonDMus Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Sir Charles Mackerras CBE Robert Threlfall Chairman Roger J. Buckley Treasurer and Membership Secretary Stewart Winstanley Windmill Ridge, 82 Highgate Road, Walsall, WS1 3JA Tel: 01922 633115 Email: [email protected] Secretary Ann Dixon 21 Woodlands Drive, Brooklands, Sale, Cheshire, M33 3PQ Tel: 0161 282 3654 Delius Journal 133.qxd 28/12/2007 12:53 Page 2 Editor Jane Armour-Chélu ****************************************************** ************************** ********************************** Website: http://www.delius.org.uk Email: [email protected] Enclosed with thisJ ournalis a copy of the revised set of Rules of The Delius Society, which under Rule 7, every member is entitled to receive. These revisions were ratified by the 2002 AGM. ISSN-0306-0373 Delius Journal 133.qxd 28/12/2007 12:53 Page 3 CONTENTS Chairman’s Message…………………………………..………………………. 5 Editorial……………………………………………...................………………. 6 ARTICLES Hiawatha – A tone poem for orchestra after Longfellow’s poem, by Robert Threlfall………...............................................................................… 7 Elegy for the Common Man, by Stewart Winstanley………………………..