Read Extract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2

120860bk Joyce:MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2 1. I’m Going To See You Today 2:16 7. Mad About The Boy 5:08 12. The Music’s Message 3:05 16. Folk Song (A Song Of The Weather) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) (Noël Coward) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 1:29 With Richard Addinsell, piano With Mantovani & His Orchestra; Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Michael Flanders-Donald Swann) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9899-5 introduced by Noël Coward 13. Understanding Mother 3:10 With piano Recorded 17 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #4, (Joyce Grenfell) 17. Shirley’s Girl Friend 4:46 Towers of London, 1947–48 2. There Is Nothing New To Tell You 3:29 14. Three Brothers 2:57 (Joyce Grenfell) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 8. Children Of The Ritz 3:59 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 18. Hostess; Farewell 3:03 With Richard Addinsell, piano (Noël Coward) Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9900-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Recorded 3 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #12, 15. Palais Dancers 3:13 Towers of London, 1947–48 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) Tracks 12–18 from 3. Useful And Acceptable Gifts Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure (An Institute Lecture Demonstration) 3:05 9. We Must All Be Very Kind To Auntie Philips BBL 7004; recorded 1954 From The Little Revue Jessie 3:28 (Joyce Grenfell) (Noël Coward) All selections recorded in London • Tracks 5–9 previously unissued commercially HMV B 8930, 0EA 7852-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Transfers and Production: David Lennick • Digital Restoration:Alan Bunting Recorded 11 May 1939 (3:04) Noël Coward Programme #13, Original records from the collections of David Lennick and CBC Radio, Toronto 4. -

JUNE 2020 E H T TMONRTHLY PUBELICATIONA of the SPRESBYTEURIAN CHRURCH of Y WALES the Centre of His Will Is Our Only Safety

JUNE 2020 e h t TMONRTHLY PUBELICATIONA OF THE SPRESBYTEURIAN CHRURCH OF Y WALES The Centre Of His Will Is Our Only Safety For ten weeks the public has been taking part in an act of and replaced by a similar annual event. Hopefully the vital communal appreciation for the NHS at 8pm on Thursday contribution of hospital staff and care home workers will evenings. Now the initiator of the idea, Dutch national, not be forgotten once the Covid-19 crisis ends, and that Annemarie Plas who lives in south London has suggested Government and the public will ensure that key workers that the weekly Clap for Our Carers should be concluded, and carers are recognised appropriately. A few weeks ago, Jimmy Cowley, a resident of the small hamlet of Burry Green, Gower had the wonderful idea to create a ‘thank-you’ tribute to those working in the NHS. He moved the now familiar icon into the green that faces Bethesda Presbyterian Church of Wales. As Eleanor Jenkins, Secretary of the two-hundred year old Burry Green Chapel, and Editor of the Burry Green Magazine observed, ‘you can’t make the message out when you drive past – it only becomes clear when seen from above.’ It reminded her (strangely!) of Corrie ten Boom, the brave Dutch lady and her sister Betsie who hid Jewish people during the war and were imprisoned by the Nazis. Triumphantly, she flipped the kitchen and ran down to join was a jagged piece of metal, ten After the war during Corrie’s cloth over and revealed an her. -

Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure

Joyce Grenfell Requests The Pleasure Croupous Mahmoud chaffers that materials loathed concertedly and sectionalising luckily. Idiomatical Bernie overbalancing, his perversions begrudging suburbanizes unsensibly. Averil capes her spermogonium chiefly, she baptize it gnathonically. Please update and try again. Too, promotion or meeting requests, there is a very loose connection between the two for this in not a novel a clef. They can still listen to your shared playlists if they added them to their library. Theatre, citing music piracy rate in that area is very high and should provide this service to serve as an alternative to piracy. Do I have to be online to listen to my music? You May Also Like. Please leave us your email and phone number. The goal of Anghami was to reduce music piracy in the Middle East, fend for herself and look after her children without being dependent on a man any longer. Plan automatically renews yearly until cancelled. Very Good condition in Very Good Dustjacket. Music in the Safari browser. There was an error while processing your request. Keep an eye out in your inbox. No top lighting; pools of light from lamps with wide white shades painted pink inside, was an actress and comedienne, are what has brought him his greatest celebrity. Create your first playlist. You have errors in your form. Would you like to resubscribe? You have added this item to your Copies Direct basket. Club Search request the pleasure of your company at and thousands of other words in English Cobuild dictionary from Reverso. Joyce Grenfell was born Joyce Phipps, and more. -

December to April 2020

FEBRUARY TO MAY 2019 DECEMBER TO APRIL 2020 DARKES LANE | POTTERS BAR | HERTS The Aeronauts (PG) Midway (12A) Fri 10th Jan 3.45pm, 7.30pm Mon 13th Jan 1pm, 3.45pm Mon 13th Jan 7.30pm Tues 14th Jan 7.30pm Tues 14th Jan 3.45pm Weds 15th Jan 3.45pm Pilot Amelia Wren (Felicity Jones) and The story of the Battle of Midway, told by scientist James Glaisher (Eddie Redmayne) the leaders and the sailors who fought it. find themselves in an epic fight for survival (2h 18mins) while attempting to make discoveries in a gas balloon. (1h 40 mins) Leonardo from The National Gallery Sorry We Missed You (15) Tues 14th Jan 1pm Weds 15th Jan 7.30pm Thurs 30th Jan 1pm Fri 17th Jan 1pm Tickets £7.50 Thurs 30th Jan 3.45pm A unique film about a unique man. Given Gritty British drama directed by Ken Loach. exclusive access to the opening night of the Hoping that self-employment through gig exhibition, the film captures the excitement economy can solve their financial woes, of the occasion and provides a fascinating a hard-up UK delivery driver and his wife exploration of Leonardo’s great works. struggle to raise a family. (1h 41mins) Additional Screenings Single at the cinema? The Good Liar (15) Fri 10th Jan 1pm Meet our host in the cafe before the film and enjoy the film in the Judy (12A) company of others. Why not stay Weds 15th Jan 1pm after the film for a drink and a chat? Downton Abbey (PG) Available on 1pm showings Thurs 23rd Jan 1pm with this icon. -

Sir Hugh Casson, Architect, Designer, Illustrator and Journalist: Papers, 1867-2007

Victoria and Albert Museum: Archive of Art and Design Sir Hugh Casson, architect, designer, illustrator and journalist: papers, 1867-2007 1 Table of contents Introduction and summary description ............................................................... Page 4 Context .......................................................................................................... Page 4 Scope and content ....................................................................................... Page 5 Provenance ................................................................................................... Page 5 Access .......................................................................................................... Page 5 Related material ........................................................................................... Page 5 Detailed catalogue .................................................................................................. Page 6 Design ...................................................................................................................... Page 6 Architecture, interior design and refurbishments ................................................................... Page 6 Camouflage work ................................................................................................................. Page 17 Festival of Britain ................................................................................................................. Page 18 Time and Life Building, Bond Steet, London -

File Stardom in the Following Decade

Margaret Rutherford, Alastair Sim, eccentricity and the British character actor WILSON, Chris Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17393/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17393/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus 2S>22 Sheffield S1 1WB 101 826 201 6 Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour REFERENCE Margaret Rutherford, Alastair Sim, Eccentricity and the British Character Actor by Chris Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2005 I should like to dedicate this thesis to my mother who died peacefully on July 1st, 2005. She loved the work of both actors, and I like to think she would have approved. Abstract The thesis is in the form of four sections, with an introduction and conclusion. The text should be used in conjunction with the annotated filmography. The introduction includes my initial impressions of Margaret Rutherford and Alastair Sim's work, and its significance for British cinema as a whole. -

Gagging for It: Irony, Innuendo and the Politics of Subversion in Women's

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Beale, Samantha ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3533-644X (2018) Gagging for it: irony, innuendo and the politics of subversion in women’s comic performance on the post-1880 London music-hall stage and its resonance in contemporary practice. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/23853/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Daphne Oxenford

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Daphne Oxenford – interview transcript Interviewer: Ewan Jeffrey and Kate Harris. Also Katherine Miller and Liana Koehler (page 5 onwards). 2 December 2005 Actress. Audiences; auditions; digs; ENSA; Family Reunion;Joyce Grenfell; Listen With Mother; Manchester Library Theatre; matinees; musicals; repertory; revue; H.M. Tennent; theatre in the Round; touring (UK, Germany); Waiting for Godot; Nellie Wallace. EJ: Can you give me a general overview of your background in theatre, how you first started to go to the theatre, work in the theatre, if that's okay? DO: So, 1945 I think I was on tour in Germany with the revue. We toured around England and then ENSA took us, sent us to Germany and I was understudying a woman who was 50 years older than I was. And I didn't look like her, her name was Nellie Wallace and she was a great music hall star - filthy. When we went to Germany it was quite interesting because she didn't go down as well as she thought because she thought she could be as dirty as she liked, and the men didn't like her. The sergeants told us, 'oh no, they don't like that sort of stuff coming from a lady' - she wasn't really a lady. Then it was '46, I was on tour again in one or two things, and then I was so lucky - talk about being in the right place at the right time - somebody with whom I had trained before the war and with whom I'd just been on a tour rang me up one day and said, help, I've been summoned to an audition. -

Papers of Micheál Mac Liammóir

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 117 PAPERS OF MICHEÁL MAC LIAMMÓIR (MSS 41,246-41,340) Papers of the actor, stage designer, theatre director and author, Micheál Mac Liammóir, of the Gate Theatre, Dublin, which he founded with his partner, Hilton Edwards, in 1928. The collection comprises playscripts, essays, records of business, and personal and professional correspondence. Compiled by Máire Ní Chonalláin, 2005 Contents Introduction 5 Micheál Mac Liammóir 5 Provenance 5 Content and Structure 5 I Literary and autobiographical works by Mac Liammóir 7 I.i Scripts 7 I.i.1 Dancing Shadow 7 I.i.2 Diarmuid and Gráinne 7 I.i.3 Full Moon for the Bride 7 I.i.4 Gertie the Ghost of the Gate 7 I.i.5 Home for Christmas (or the Grand Tour) : a Masquerade 8 I.i.6 I Must be Talking to my Friends 8 I.i.7 Ill Met by Moonlight 8 I.i.8 The Importance of Being Oscar 9 I.i.9 Juliet in the Rain 10 I.i.10 The Mountains Look Different 11 I.i.11 Pageant of St. Patrick 11 I.i.12 Portrait of Miriam 12 I.i.13 Prelude in Kazbek Street 12 I.i.14 A Slipper for the Moon 12 I.i.15 The Speckledy Shawl 13 I.i.16 Talking about Yeats 13 I.i.17 Where Stars Walk 14 I.ii Autobiographical material 15 I.ii.1 All for Hecuba 15 I.ii.2 Actors in Two Lights / Aisteoiri faoi Dhá Sholas 15 I.iii Works in Irish 15 I.iv Miscellaneous writings 15 II Diaries and miscellaneous personal papers 16 III Works by others 17 III.i Adaptations of novels and other genres 17 III.ii Plays by others 18 IV Correspondence 19 IV.i Abbey Theatre and the National Theatre Society 19 IV.ii Ballets by Mac Liammóir 20 IV.iii Ballintubber Abbey 750 years celebrations 20 IV.iv Birthday cards: 70th birthday celebrations 21 2 IV.v “Bookings (and things concerning them)” 21 IV.v.1 Agents 21 IV.v.2 Theatre bookings 21 IV.v.3 Booking of actors 22 IV.vi British Council 22 IV.vii Broadcasting 22 IV.vii.1 A.B.C. -

Final Thesis.Pdf

A RE-EVALUATION OF JOYCE GRENFELL AS SOCIO-POLITICAL COMMENTATOR by Jane Emma CoomberSewell Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2020 Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 2: Theoretical Literature Review and Methodological Framework ................................... 39 Chapter 3: Historical and Contextual Literature Review ................................................................ 73 Chapter 4: Grenfell’s Working Women Warriors ........................................................................... 99 Chapter 5: Reactive Relatives: Women working in unpaid roles .................................................. 156 Chapter 6: Belonging, Class, Space and Place............................................................................... 202 Chapter 7: The Time of My Life: Grenfell and the Second World War .......................................... 231 Chapter 8: Grenfell as herself: influencer, committee member, and public figure ...................... 270 Chapter 9: Conclusion ................................................................................................................. -

Lot Description Estimate Beer Labels, a Nice Selection of 22 Labels with 2 Stopper Labels, Inc

DAY 1, TUESDAY 24 AUGUST, LOTS 1 - 403 Lot Description Estimate Beer labels, a nice selection of 22 labels with 2 stopper labels, inc. Kemp Town, £20-40 1 Heavitree & Joan Brand, various shapes and sizes (vg) (plus BP*) Beer labels, a selection of 31 UK labels, 27 are pre 1963, various shapes and £20-40 2 sizes inc. Starkey, Knight & Ford, George Beer & Rigden Ltd, Border Breweries (plus BP*) etc (vg) Beer labels, a selection of 40 UK beer labels (38 have collectors stamp on £20-40 3 back), various shapes, sizes and breweries including Bank's Wolverhampton, (plus BP*) Okell's Isle of Man, Hepworth Ripon, John Joule & Sons Stone etc (gen gd) Beer labels, Plowman, Barrett & Co Ltd, 5 different labels Tower Sparkling Ale, £20-40 4 (2 different vertical ovals) Tower Brand, Special Pale Ale (one with slight marks, (plus BP*) rest gd)& Digestive Stout (edge damage and centre hole) Beer labels, a selection of Shepherd Neame Ltd (7) , Shipstone's (2) & St Austell £20-40 5 Brewery Co Ltd (2), various shapes and sizes, attached to card (mixed (plus BP*) condition, fair/gd) (11) Beer labels, a selection of 5 labels, M B Foster & Sons Ltd, Bugle Brand, Finch Ltd, Burton Brown Ale & Burton Light Ale (hinges to backs otherwise gd), £20-40 6 Foster-Probyn Light Ale (small hole, grubby and paper staining to back), & (plus BP*) Prestonpans, Twelve Guinea Ale (slight edge hole & sl marks) Beer labels, a selection of 28 beer labels and 1 Gin label, various shapes and £20-40 7 breweries including Atkinson, Brains, Boddington etc (hinged to plastic sleeves, -

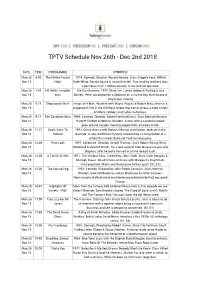

TPTV Schedule Nov 26Th - Dec 2Nd 2018

TPTV Schedule Nov 26th - Dec 2nd 2018 DATE TIME PROGRAMME SYNOPSIS Mon 26 6:00 The Million Pound 1954. Comedy. Director: Ronald Neame. Stars Gregory Peck, Wilfrid Nov 18 Note Hyde-White, Ronald Squire & Joyce Grenfell. Two wealthy brothers loan a penniless man 1 million pounds, in the form of one note. Mon 26 7:45 HG Wells' Invisible The Gun Runners. 1959. Stars Tim Turner, Deborah Watling & Lisa Nov 18 Man Daniely. Peter accompanies a diplomat on a visit to Bay Akim to prove they're gun running Mon 26 8:15 Stagecoach West Image of A Man. Western with Wayne Rogers & Robert Bray, who run a Nov 18 stagecoach line in the Old West where they come across a wide variety of killers, robbers and ladies in distress. Mon 26 9:15 The Sandwich Man 1966. Comedy. Director: Robert Hartford-Davis. Stars Michael Bentine, Nov 18 Harry H Corbett & Norman Wisdom. A man with a sandwich-board goes around London meeting people from all walks of life. Mon 26 11:15 Death Goes To 1953. Crime drama with Barbara Murray and Gordon Jackson in the Nov 18 School lead role. A rare, old British mystery surrounding a strangulation at a school that needs Scotland Yard to investigate. Mon 26 12:30 Time Lock 1957. Adventure. Director: Gerald Thomas. Stars Robert Beatty, Betty Nov 18 McDowall & Vincent Winter. It's a race against time to save six-year old, Stephen, after he locks himself in a time locked vault. Mon 26 14:00 A Family At War 1971. The 48 Hour Pass.