Radiophonic Writing at the BBC, 1945-1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Download Further Requirements: Interviews

FURTHER REQUIREMENTS: INTERVIEWS, BROADCASTS, STATEMENTS AND REVIEWS, 1952-85 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Philip Larkin,Anthony Thwaite | 416 pages | 04 Nov 2002 | FABER & FABER | 9780571216147 | English | London, United Kingdom Further Requirements: Interviews, Broadcasts, Statements and Reviews, 1952-85 PDF Book When you have read it, take me by the hand As children do, loving simplicity. Shopbop Designer Modemarken. In Thwaite's poems there is rarely much in the way of display and few extravagant local effects. Geben Sie Feedback zu dieser Seite. Andere Formate: Gebundenes Buch , Taschenbuch. Cookies akzeptieren Cookie-Einstellungen anpassen. Thwaite is also an accomplished comic poet. Author statement 'If I could sum up my poetry in a few well-chosen words, the result might be a poem. Entdecken Sie jetzt alle Amazon Prime-Vorteile. Poetry and What is Real. Philip Larkin remains England's best-loved poet - a writer matchlessly capable of evoking his native land and of touching all readers from the most sophisticated intellectual to the proverbial common reader. Etwas ist schiefgegangen. Next page. Weitere Informationen bei Author Central. Philip Larkin. Anthony Thwaite. While Larkin views them in terms of the personal life, or at most, of England, Thwaite, who has travelled widely and worked overseas for extended periods, can also find them in an alien setting, for example in North Africa. Previous page. Artists, cultural professionals and art collective members in the UK and Southeast A… 1 days ago. Sind Sie ein Autor? Urbane, weary, aphoristic, certain that nothing and everything changes, the poems draw both on Cavafy and Lawrence Durrell. This entirely new edition brings together all of Philip Larkin's poems. -

Back from the Fourth Dimension Paddy Kingsland

Back From The Fourth Dimension Paddy Kingsland Posted: April 22, 2014 robinthefog.com/2014/04/22/back-from-the-fourth-dimension-paddy-kingsland/ As promised, following last week’s report for BBC World Service, here is the first of four interviews with the veterans of the Radiophonic Workshop, the ‘Godfathers of British Electronic Music’, now reformed and touring their collection of vintage analogue equipment and classic radiophonic works to rapturous reception. They’ll be featured in the order I interviewed them two weeks ago at the University of Chichester, so we’re starting with synthesiser legend Paddy Kingsland; the man who definitely put the ‘funk’ into radiophonics. Best known for The Fourth Dimension LP (essentially a Kingsland solo album), he has a string of classic BBC themes to his name, as well as providing incidental music for such classics as Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Dr. Who and many more. Paddy has also recorded solo albums, made library music and jingles for KPM and worked alongside composers such as Michael Nyman. His signature sound is melodic synthesiser workouts with a strong rhythmic back-bone and the track ‘Vespucci’ is a highlight of their revived set-list. This interview, slightly truncated here, took place in the artist’s green room at Chichester University; with moderate interruptions from the air conditioning... ! PK: I worked at the Radiophonic Workshop for the BBC between 1970 and 1981, which is quite a long time ago now. Of course I’ve done quite a lot of other things since then, but more recently I was approached by some other friends who worked at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and was asked if I‘d be interested in doing some gigs with them – some live events. -

The Focus Group and Belbury Poly by Mark Fisher

Nostalgia for Modernism: The Focus Group and Belbury Poly ‘Myself and my friend Jim Jupp had been making music, independently and together for a while, and also obsessing over the same things – the cosmic horror of Machen, Lovecraft, the Radiophonic Workshop, weird folk and the occult. We realised that we wanted to put our music out, but also create our own world where we could play with all these reference points. Starting our own label was the only way to do it.’ Julian House is describing how he and his school-friend Jim Jupp came to found the Ghost Box label. Off-kilter bucolic, drenched in an over-exposed post-psyche-delic sun, Ghost Box recordings are uneasy listening to the letter. If nostalgia famously means ‘homesickness’, then Ghost Box sound is about unhomesickness, about the uncanny spectres entering the domestic environment through the cathode ray tube. At one level, the Ghost Box is television itself; or a television that has disappeared, itself become a ghost, a conduit to the Other Side, now only remembered by those of a certain age. No doubt there comes a point when every generation starts pining for the artefacts of its childhood – but was there something special about the TV of the 1970s which Ghost Box releases obsessively reference? ‘I think there definitely was something powerful about the children’s TV from that period,’ House maintains. ‘I think it was just after the 60s, these musicians and animators, film makers had come through the psychedelic thing and acid folk, they had these strange dark obsessions that they put into their TV programmes. -

This Week's Essential Reading

10 Friday, December 3, 2010 www.thenational.ae The N!tion!l thereview The N!tion!l thereview Friday, December 3, 2010 www.thenational.ae 11 this week’s essential reading ‘From Rising Skirt Lengths to the If ‘mood polarity’ is negative, then markets falter. Horror movies are popular, people buy Collapse of World Powers’ by Michelle drab cars and governments favour protectionist policies. That’s socionomics, so-called } music { Baddeley, Times Higher Education playlist " From Halim El-Dabh to the theremin – a look back into early incarnations of synthesised sound Resonant freq uencies Halim El-Dabh Crossing into the Electric Magnetic Without Fear (2000) The Egyptian composer’s electronic experiments include A new book details the history of the ess, whether that be a composer recordings from the Columbia- writing down notes or a musi- Princeton Electronic Music BBC Radiophonic Workshop and its cian playing them. Few people hear a soaring string quartet and Studios in the 1950s, and boundary-breaking adventures in attribute its power merely to a material made in a Cairo radio maestro’s fleeting moods, or the station 1944, which may be the electronic music, writes Andy Battaglia wood and steel of a violin. But first treated music in history. even fewer of us can hear a work El-Dabh’s curiosity has led him For all the ways they can sound The broadcast in question was an of electronic music and even try along many low-tech paths, too. strange now, it’s hard to imagine experimental spoken-word show to guess at its origins – at its real how alien the earliest electronic called Private Dreams and Public causes and effects. -

Service Review

Editorial Standards Findings Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered by the Editorial Standards Committee December 2012 issued February 2013 Getting the best out of the BBC for licence fee payers Editorial Standards Findings/Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered Contentsby the Editorial Standards Committee Remit of the Editorial Standards Committee 2 Summaries of findings 4 Appeal Findings 6 Silent Witness, BBC One, 22 April 2012, 9pm 6 Application of Expedited Procedure at Stage 1 14 News Bulletins, BBC Radio Shropshire, 26 & 27 March 2012 19 Watson & Oliver, BBC Two, 7 March 2012, 7.30pm 26 Rejected Appeals 38 5 live Investigates: Cyber Stalking, BBC Radio 5 live and Podcast, 1 May 2011; and Cyber- stalking laws: police review urged, BBC Online, 1 May 2011 38 Olympics 2012, BBC One, 29 July 2012 2 Today, BBC Radio 4, 29 May 2012 5 Bang Goes the Theory, BBC One, 16 April 2012 9 Have I Got News For You, BBC Two, 27 May 2011and Have I Got A Bit More News For You, 2 May 2012 16 Application of expedited complaint handling procedure at Stage 1 21 Look East, BBC One 24 December 2012 issued February 2013 Editorial Standards Findings/Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered by the Editorial Standards Committee Remit of the Editorial Standards Committee The Editorial Standards Committee (ESC) is responsible for assisting the Trust in securing editorial standards. It has a number of responsibilities, set out in its Terms of Reference at http://www.bbc.co.uk/bbctrust/assets/files/pdf/about/how_we_operate/committees/2011/esc_t or.pdf. -

Discographic Workshop Part 3A – Doctor Who Theme (RESL 11)

http://bbcrecords.co.uk/blog/?p=717 Discographic Workshop Part 3A – Doctor Who Theme (RESL 11) Doctor Who We (ahem) materialise into the third part (and half-way point) of a thorough review of all the BBC Records (& Tapes) releases featuring the Radiophonic Workshop. Previous parts have taken an in-depth look at the compilation albums and the solo LPs. This part is all about the Workshop’s many dealings with The Doctor and this post is dedicated the first such release. Doctor Who (hereafter, DW) began on BBC TV in 1963, and with a little help from the Daleks, was a ratings smash hit, reaching viewing figures of 12 million. The show continued to be hugely popular right through to the eighties, when it finally lost its footing and was cancelled after series number 26, in 1989. Of course, it was resurrected in 2005 and continues to this day, as exciting and popular as ever, but here we’re going to look back to the golden age of the original series. The BBC Radiophonic Workshop were part of DW production from the very start and did much to contribute to the success of the show in its early days. Initially, theme music and sound effects, then later the incidental music was augmented at the Workshop and finally, for a period, all the show’s music was coming from their Maida Vale studios. Any Radiophonic music was extremely time consuming to produce in 1963 however, and until the advent of relatively cheap and playable keyboard synthesizers, along with high quality multi- track recorders, it simply wasn’t practical from the Workshop to soundtrack hours and hours of television every year. -

The Forties: a Doctorate in Creative and Critical Writing

The Forties: A Doctorate in Creative and Critical Writing Todd Swift Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD University of East Anglia Faculty of Humanities School of Literature and Creative Writing August, 2011 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK copyright law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. ABSTRACT Todd Swift, 2011, ‗The Forties: A Doctorate in Creative and Critical Writing‘ This work is in two parts: a portfolio of creative writing (poetry), preceded by a critical thesis. In the critical aspect of my dissertation I contest a dominant account of poetic creation and influence in the period 1938–1954, and consider a third line of influence that arose in post-war British poetry. The methodology follows in the footsteps of Other Traditions by John Ashbery: literary criticism by a practitioner. My critical writing complements my poetry collection, whose various styles and registers relate to the poetic influences discussed. My first three chapters develop the argument as follows: Chapter One considers ideas of ‗style‘ and ‗poetic style‘. Chapter Two narrows in on the idea of ‗period style‘ in poetry and turns more specifically into a discussion of the Forties Style in Poetry. Chapter Three looks directly at the period under question, the Forties, and its key poet, Dylan Thomas, as read by critics. Chapter Four discusses F.T. Prince, a major poet much overlooked. -

British Radio Drama and the Avant-Garde in the 1950S

British radio drama and the avant-garde in the 1950s Hugh Chignell 1 Bournemouth University, UK Correspondence: Professor Hugh Chignell, Faculty of Media and Communication, Bournemouth University, Poole, Dorset, BH12 5BB, UK. +44 (0)1202 961393 Email: [email protected] 1 British radio drama and the avant-garde in the 1950s Abstract The BBC in the 1950s was a conservative and cautious institution. British theatre was at the same time largely commercial and offered a glamorous distraction from wider social and political realities. During the decade, however, new avant-garde approaches to drama emerged, both on the stage and on radio. The avant-garde was particularly vibrant in Paris where Samuel Beckett was beginning to challenge theatrical orthodoxies. Initially, managers and producers in BBC radio rejected a radio version of Beckett’s, Waiting for Godot and other experimental work was viewed with distaste but eventually Beckett was accepted and commissioned to write All That Fall (1957), a masterpiece of radio drama. Other Beckett broadcasts followed, including more writing for radio, extracts from his novels and radio versions of his stage plays as well as plays by the experimental radio dramatist, Giles Cooper. This article examines the different change agents which enabled an initially reluctant BBC to convert enthusiastically to the avant-garde. A networked group of younger producers, men and women, played a vital role in the acceptance of Beckett as did the striking pragmatism of senior radio managers. A willingness to accept the transnational cultural flow from Paris to London was also an important factor. The attempt to reinvent radio drama using ‘radiophonic’ sound effects (pioneered in Paris) was another factor for change and this was encouraged by growing competition from television drama on the BBC and ITV. -

Delia Derbyshire Sound and Music for the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, 1962-1973

Delia Derbyshire Sound and Music For The BBC Radiophonic Workshop, 1962-1973 Teresa Winter PhD University of York Music June 2015 2 Abstract This thesis explores the electronic music and sound created by Delia Derbyshire in the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop between 1962 and 1973. After her resignation from the BBC in the early 1970s, the scope and breadth of her musical work there became obscured, and so this research is primarily presented as an open-ended enquiry into that work. During the course of my enquiries, I found a much wider variety of music than the popular perception of Derbyshire suggests: it ranged from theme tunes to children’s television programmes to concrete poetry to intricate experimental soundscapes of synthesis. While her most famous work, the theme to the science fiction television programme Doctor Who (1963) has been discussed many times, because of the popularity of the show, most of the pieces here have not previously received detailed attention. Some are not widely available at all and so are practically unknown and unexplored. Despite being the first institutional electronic music studio in Britain, the Workshop’s role in broadcasting, rather than autonomous music, has resulted in it being overlooked in historical accounts of electronic music, and very little research has been undertaken to discover more about the contents of its extensive archived back catalogue. Conversely, largely because of her role in the creation of its most recognised work, the previously mentioned Doctor Who theme tune, Derbyshire is often positioned as a pioneer in the medium for bringing electronic music to a large audience. -

Call No. Responsibility Item Publication Details Date Note 1

Call no. Responsibility Item Publication details Date Note TKNC0001 Roberts, H. Song, to a gay measure Dublin: printed at the Dolmen 1951 "200 copies." Neville Press TKNC0002 Promotional notice for Travelling tinkers, a book of Dolmen Press ballads by Sigerson Clifford TKNC0003 Promotional notice for Freebooters by Mauruce Kennedy Dolmen Press TKNC0004 Advertisement for Dolmen Press Greeting cards &c Dolmen Press TKNC0005 The reporter: the magazine of facts and ideas. Volume July 16, 1964 contains 'In the 31 no. 2 beginning' (verse) by Thomas Kinsella TKNC0006 Clifford, Travelling tinkers Dublin: Dolmen Press 1951 Of one hundred special Sigerson copies signed by the author this is number 85. Insert note from Thomas Kinsella. TKNC0007 Kinsella, Thomas The starlit eye / Thomas Kinsella ; drawings by Liam Dublin: Dolmen Press 1952 Set and printed by hand Miller at the Dolmen Press, Dublin, in an edition of 175 copies. March 1952. (p. [8]). TKNC0008 Kinsella, Thomas Galley proof of Poems [Glenageary, County Dublin]: 1956 Galley proof Dolmen Press TKNC0009 Kinsella, Thomas The starlit eye / Thomas Kinsella ; drawings by Liam Dublin : Dolmen Press 1952 Of twenty five special Miller copies signed by the author this is number 20. Set and printed by hand at the Dolmen Press, Dublin, in an edition of 175 copies. March 1952. TKNC0010 Promotional postcard for Love Duet from the play God's Dolmen Press gentry by Donagh MacDonagh TKNC0011 Irish writing. No. 24 Special issue - Young writers issue Dublin Sep-53 1 Thomas Kinsella Collection Listing Call no. Responsibility Item Publication details Date Note TKNC0012 Promotional notice for Dolmen Chapbook 3, The perfect Dolmen Press 1955 wife a fable by Robert Gibbings with wood engravings by the author TKNC0013 Pat and Mick Broadside no. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who and the Leisure Hive by David Fisher Doctor Who and the Leisure Hive by David Fisher

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who and the Leisure Hive by David Fisher Doctor Who and the Leisure Hive by David Fisher. The Doctor and Romana travel to the Leisure Hive on Argolis, a planet ravaged by a nuclear war with the Foamasi years earlier. The Argolin leader, Mena, explains that her people are now sterile and the Hive is their legacy, intended to bring different races together in the spirit of peace. The main attraction is a device called the Tachyon Recreation Generator, but it is experiencing mysterious faults. At the same time, Mena's son, Pangol, becomes increasingly militant; the scientist Hardin conducts fraudulent temporal experiments; an Earth businessman, Brock, behaves very oddly; and mysterious creatures prowl the Leisure Hive. Production. Throughout the incubation of Doctor Who 's seventeenth season, the outgoing team of producer Graham Williams and script editor Douglas Adams had tried unsuccessfully to attract new writers to the programme. As a result, they had found themselves relying on veteran Doctor Who contributors, while also leaving few viable scripts in development for Williams' successor, John Nathan-Turner. Despite these struggles, Nathan- Turner was eager to attract not only new writers, but also new directors to Season Eighteen. However, he and executive producer Barry Letts were also keen to rein in the programme's humorous and fantastical tendencies, in favour of a renewed emphasis on more legitimate science. This was out of keeping with those few narratives -- such as Pennant Roberts' “Erinella” and Alan Drury's “The Tearing Of The Veil” -- that remained available for consideration. With no script editor in place when he took over as producer in December 1979, this forced Nathan-Turner to turn to a familiar Doctor Who name: David Fisher. -

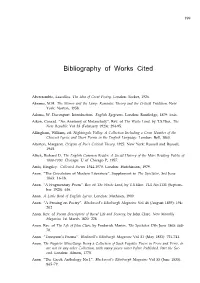

Bibliography of Works Cited

199 Bibliography of Works Cited Abercrombie, Lascelles. The Idea of Great Poetry. London: Secker, 1926. Abrams, M.H. The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition. New York: Norton, 1958. Adams, W. Davenport. Introduction. English Epigrams. London: Routledge, 1879: i-xix. Aiken, Conrad. “An Anatomy of Melancholy”. Rev. of The Waste Land, by T.S.Eliot. The New Republic Vol 33 (February 1923): 294-95. Allingham, William, ed. Nightingale Valley: A Collection Including a Great Number of the Choicest Lyrics and Short Poems in the English Language. London: Bell, 1860. Alterton, Margaret. Origins of Poe’s Critical Theory. 1925. New York: Russell and Russell, 1965. Altick, Richard D. The English Common Reader. A Social History of the Mass Reading Public of 1800-1900. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1957. Amis, Kingsley. Collected Poems 1944-1979. London: Hutchinson, 1979. Anon. “The Circulation of Modern Literature”. Supplement to The Spectator, 3rd June 1863: 16-18. Anon. “A Fragmentary Poem”. Rev of The Waste Land, by T.S.Eliot. TLS No.1131 (Septem- ber 1923): 616. Anon. A Little Book of English Lyrics. London: Methuen, 1900. Anon. “A Prosing on Poetry”. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine Vol 46 (August 1839): 194- 202. Anon. Rev. of Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery, by John Clare. New Monthly Magazine 1st March 1820: 228 Anon. Rev. of The Life of John Clare, by Frederick Martin. The Spectator 17th June 1865: 668- 70. Anon. “Tennyson’s Poems”. Blackwell’s Edinburgh Magazine Vol 31 (May 1832): 721-741. Anon. The Fugitive Miscellany: Being a Collection of Such Fugitive Pieces in Prose and Verse, as are not in any other Collection, with many pieces never before Published.