This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2

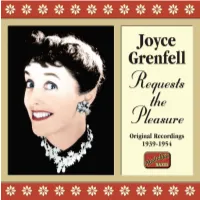

120860bk Joyce:MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2 1. I’m Going To See You Today 2:16 7. Mad About The Boy 5:08 12. The Music’s Message 3:05 16. Folk Song (A Song Of The Weather) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) (Noël Coward) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 1:29 With Richard Addinsell, piano With Mantovani & His Orchestra; Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Michael Flanders-Donald Swann) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9899-5 introduced by Noël Coward 13. Understanding Mother 3:10 With piano Recorded 17 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #4, (Joyce Grenfell) 17. Shirley’s Girl Friend 4:46 Towers of London, 1947–48 2. There Is Nothing New To Tell You 3:29 14. Three Brothers 2:57 (Joyce Grenfell) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 8. Children Of The Ritz 3:59 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 18. Hostess; Farewell 3:03 With Richard Addinsell, piano (Noël Coward) Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9900-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Recorded 3 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #12, 15. Palais Dancers 3:13 Towers of London, 1947–48 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) Tracks 12–18 from 3. Useful And Acceptable Gifts Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure (An Institute Lecture Demonstration) 3:05 9. We Must All Be Very Kind To Auntie Philips BBL 7004; recorded 1954 From The Little Revue Jessie 3:28 (Joyce Grenfell) (Noël Coward) All selections recorded in London • Tracks 5–9 previously unissued commercially HMV B 8930, 0EA 7852-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Transfers and Production: David Lennick • Digital Restoration:Alan Bunting Recorded 11 May 1939 (3:04) Noël Coward Programme #13, Original records from the collections of David Lennick and CBC Radio, Toronto 4. -

How Float Glass Is Produced?-MORN BM

QINGDAO MORN BUILDING MATERIALS CO.,LTD Your turnkey China tempered glass/laminated glass/insulated glass supplier How float glass is produced?-MORN BM The float glass process is also known as the Pilkington process, named after the British glass manufacturer Pilkington, which pioneered the technique (invented by Sir Alastair Pilkington) in the 1950s at their production site in St Helens, Merseyside. Float glass,mostly are soda-lime glass, is made by floating molten glass on a bed of molten metal- tin, This method gives the sheet uniform thickness and very flat surfaces.Which makes it easy to be further processed-heat treated glass(tempered glass,heat soaked glass,heat strengthened glass),laminated glass,and low-E coated insulated glass panels to enhance its strength,safety and insulation performance. Here is a video shows how the float glass is produced: https://youtu.be/fNmbGyIBnFs OK,here are more details: https://youtu.be/2T9a59z7p6E Float glass is the mostly popular production methods and will last long time till new and more cost efficient methods developed. Morn Building materials is your turnkey architectural glass supplier in China,welcome contact us for more info. Tags: FLOAT GLASS, float glass productin, float glass production line, heat soaked glass, heat strengthened glass, Heat treated glass, laminated glass, low-E coated insulated glass panels, tempered glass Add:Room A304,Shengxifu Road,NO.209 Weihai Road,Shibei Di1strict,Qingdao,China,266024 [email protected] QINGDAO MORN BUILDING MATERIALS CO.,LTD Your turnkey China tempered glass/laminated glass/insulated glass supplier About Morn Building Materials: Morn Building Materials Co.,Ltd is trading company offering the right facade materials for a wide range of applications for architectural,design and system requirements.Cooperating with China premium glass fabricators,Morn is able to supply whatever glass products applied in facade,Spandrel ,roof ,handrail,partition,balustrade,canopy,greenhouse,sun room ,interior exterior application. -

Estimating the Effects of Fiscal Policy in OECD Countries

Estimating the e®ects of ¯scal policy in OECD countries Roberto Perotti¤ This version: November 2004 Abstract This paper studies the e®ects of ¯scal policy on GDP, in°ation and interest rates in 5 OECD countries, using a structural Vector Autoregression approach. Its main results can be summarized as follows: 1) The e®ects of ¯scal policy on GDP tend to be small: government spending multipliers larger than 1 can be estimated only in the US in the pre-1980 period. 2) There is no evidence that tax cuts work faster or more e®ectively than spending increases. 3) The e®ects of government spending shocks and tax cuts on GDP and its components have become substantially weaker over time; in the post-1980 period these e®ects are mostly negative, particularly on private investment. 4) Only in the post-1980 period is there evidence of positive e®ects of government spending on long interest rates. In fact, when the real interest rate is held constant in the impulse responses, much of the decline in the response of GDP in the post-1980 period in the US and UK disappears. 5) Under plausible values of its price elasticity, government spending typically has small e®ects on in°ation. 6) Both the decline in the variance of the ¯scal shocks and the change in their transmission mechanism contribute to the decline in the variance of GDP after 1980. ¤IGIER - Universitµa Bocconi and Centre for Economic Policy Research. I thank Alberto Alesina, Olivier Blanchard, Fabio Canova, Zvi Eckstein, Jon Faust, Carlo Favero, Jordi Gal¶³, Daniel Gros, Bruce Hansen, Fumio Hayashi, Ilian Mihov, Chris Sims, Jim Stock and Mark Watson for helpful comments and suggestions. -

Introduction to Macroeconomics Lecture Notes

Introduction to Macroeconomics Lecture Notes Robert M. Kunst March 2006 1 Macroeconomics Macroeconomics (Greek makro = ‘big’) describes and explains economic processes that concern aggregates. An aggregate is a multitude of economic subjects that share some common features. By contrast, microeconomics treats economic processes that concern individuals. Example: The decision of a firm to purchase a new office chair from com- pany X is not a macroeconomic problem. The reaction of Austrian house- holds to an increased rate of capital taxation is a macroeconomic problem. Why macroeconomics and not only microeconomics? The whole is more complex than the sum of independent parts. It is not possible to de- scribe an economy by forming models for all firms and persons and all their cross-effects. Macroeconomics investigates aggregate behavior by imposing simplifying assumptions (“assume there are many identical firms that pro- duce the same good”) but without abstracting from the essential features. These assumptions are used in order to build macroeconomic models.Typi- cally, such models have three aspects: the ‘story’, the mathematical model, and a graphical representation. Macroeconomics is ‘non-experimental’: like, e.g., history, macro- economics cannot conduct controlled scientific experiments (people would complain about such experiments, and with a good reason) and focuses on pure observation. Because historical episodes allow diverse interpretations, many conclusions of macroeconomics are not coercive. Classical motivation of macroeconomics: politicians should be ad- vised how to control the economy, such that specified targets can be met optimally. policy targets: traditionally, the ‘magical pentagon’ of good economic growth, stable prices, full employment, external equilibrium, just distribution 1 of income; according to the EMU criteria, focus on inflation (around 2%), public debt, and a balanced budget; according to Blanchard,focusonlow unemployment (around 5%), good economic growth, and inflation (0—3%). -

Local Commercial Radio Content

Local commercial radio content Qualitative Research Report Prepared for Ofcom by Kantar Media 1 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 2 1 Executive summary .................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Summary of key findings .......................................................................................................... 5 2 Background and objectives ..................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 10 2.2 Research objectives ............................................................................................................... 10 2.3 Research approach and sample ............................................................................................ 11 2.3.1 Overview ............................................................................................................................. 11 2.3.2 Workshop groups: approach and sample ........................................................................... 11 2.3.3 Research flow summary .................................................................................................... -

London Calling: BBC External Services, Whitehall and the Cold War 1944- 57

London calling: BBC external services, Whitehall and the cold war 1944- 57. Webb, Alban The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1577 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] LONDON CALLING: SSC EXTERNAL SERVICES, WHITEHALL AND THE COLD WAR, 1944-57 ALBAN WEBB Queen Mary College, University of London A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) 1 Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: '~"\ ~~Ue6b Alban Webb Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: Alban Webb ABSTRACT The Second World War had radically changed the focus of the BBC's overseas operation from providing an imperial service in English only, to that of a global broadcaster speaking to the world in over forty different languages. The end of that conflict saw the BBC's External Services, as they became known, re-engineered for a world at peace, but it was not long before splits in the international community caused the postwar geopolitical landscape to shift, plunging the world into a cold war. At the British government's insistence a re-calibration of the External Services' broadcasting remit was undertaken, particularly in its broadcasts to Central and Eastern Europe, to adapt its output to this new and emerging world order. -

JUNE 2020 E H T TMONRTHLY PUBELICATIONA of the SPRESBYTEURIAN CHRURCH of Y WALES the Centre of His Will Is Our Only Safety

JUNE 2020 e h t TMONRTHLY PUBELICATIONA OF THE SPRESBYTEURIAN CHRURCH OF Y WALES The Centre Of His Will Is Our Only Safety For ten weeks the public has been taking part in an act of and replaced by a similar annual event. Hopefully the vital communal appreciation for the NHS at 8pm on Thursday contribution of hospital staff and care home workers will evenings. Now the initiator of the idea, Dutch national, not be forgotten once the Covid-19 crisis ends, and that Annemarie Plas who lives in south London has suggested Government and the public will ensure that key workers that the weekly Clap for Our Carers should be concluded, and carers are recognised appropriately. A few weeks ago, Jimmy Cowley, a resident of the small hamlet of Burry Green, Gower had the wonderful idea to create a ‘thank-you’ tribute to those working in the NHS. He moved the now familiar icon into the green that faces Bethesda Presbyterian Church of Wales. As Eleanor Jenkins, Secretary of the two-hundred year old Burry Green Chapel, and Editor of the Burry Green Magazine observed, ‘you can’t make the message out when you drive past – it only becomes clear when seen from above.’ It reminded her (strangely!) of Corrie ten Boom, the brave Dutch lady and her sister Betsie who hid Jewish people during the war and were imprisoned by the Nazis. Triumphantly, she flipped the kitchen and ran down to join was a jagged piece of metal, ten After the war during Corrie’s cloth over and revealed an her. -

“Rule Number Two Is Doctors Can't Change Rule Numb-1 REFORMAT

Britain’s Television Act of 1954: One Medium’s Effect on a Society Joshua Altman Professor Dane Kennedy 20 th Century Britain May 5, 2008 Joshua Altman Britain’s Television Act of 1954 May 5, 2008 INTRODUCTION When television came to the British masses it signaled the beginnings of a metamorphosis that was beyond suppression. Decades of a BBC monopoly provided a culturally unifying factor in both television and radio, but the Television Act of 1954 ended that monopoly, thus ending the unifying force 1. While debating the Act in Parliament, Ian Harvey MP said “Television is an instrument of communication and I am amongst those who believe that an instrument of such power of communication should not be vested in one single authority 2” The nature of British television changed with the Television Act of 1954. For the first time British broadcasting was open to competition and entities other than the BBC were able to produce content to air on channels other than the BBC 3. One condition of open broadcasting was that content had to be monitored, as it was no longer all created by the government. Created by the Television Act of 1954, the Independent Television Authority [ITA] took television one step further away from government regulation by functioning as an oversight body for Independent Television [ITV]. The ITA was responsible for licensing stations [franchises] and providing closer monitoring of content to ensure that it was appropriate for broadcast. Primarily, Members of Parliament concerned themselves with two major questions, the first being how television programming would be supported financially. -

Wilson, MI5 and the Rise of Thatcher Covert Operations in British Politics 1974-1978 Foreword

• Forward by Kevin McNamara MP • An Outline of the Contents • Preparing the ground • Military manoeuvres • Rumours of coups • The 'private armies' of 1974 re-examined • The National Association for Freedom • Destabilising the Wilson government 1974-76 • Marketing the dirt • Psy ops in Northern Ireland • The central role of MI5 • Conclusions • Appendix 1: ISC, FWF, IRD • Appendix 2: the Pinay Circle • Appendix 3: FARI & INTERDOC • Appendix 4: the Conflict Between MI5 and MI6 in Northern Ireland • Appendix 5: TARA • Appendix 6: Examples of political psy ops targets 1973/4 - non Army origin • Appendix 7 John Colin Wallace 1968-76 • Appendix 8: Biographies • Bibliography Introduction This is issue 11 of The Lobster, a magazine about parapolitics and intelligence activities. Details of subscription rates and previous issues are at the back. This is an atypical issue consisting of just one essay and various appendices which has been researched, written, typed, printed etc by the two of us in less than four months. Its shortcomings should be seen in that light. Brutally summarised, our thesis is this. Mrs Thatcher (and 'Thatcherism') grew out of a right-wing network in this country with extensive links to the military-intelligence establishment. Her rise to power was the climax of a long campaign by this network which included a protracted destabilisation campaign against the Liberal and Labour Parties - chiefly the Labour Party - during 1974-6. We are not offering a conspiracy theory about the rise of Mrs Thatcher, but we do think that the outlines of a concerted campaign to discredit the other parties, to engineer a right-wing leader of the Tory Party, and then a right-wing government, is visible. -

Laminated Glass Insulating Glass Fire Rated Glass Burglar Resistant Glass Sound Protection Glass Decorative Glass Curved Glass

Envelopes in Architecture (A4113) Designing holistic envelopes for contemporary buildings Silvia Prandelli, Werner Sobek New York A4113 ENVELOPES IN ARCHITECTURE - FALL 2016 Supply chain for holistic facades 2 Systems Door systems Media Facades Rainscreen facades Dynamic facades Mesh System Structural glass/Cable Glass floors Multiple skins Shading systems Green facades Panelized systems Stick/Unitized systems 3 Curtain wall facades 4 What are the components of a façade system? 5 What are the components of a façade system? 6 What are the components of a façade system? 7 Glass 8 Glass Types Base Glass (float glass) Heat Treated Glass Laminated Glass Insulating Glass Fire Rated Glass Burglar Resistant Glass Sound Protection Glass Decorative Glass Curved Glass 9 Base Glass (Float Glass) 10 3500 BC Glass Making: Man-made glass objects, mainly non-transparent glass beads, finds in Egypt and Eastern Mesopotamia 1500 BC Early hollow glass production: Evidence of the origins of the hollow glass industry, finds in Egypt 11 27 BC - 14 AD Glass Blowing: Discovery of glassblowing, attributed to Syrian craftsmen from the Sidon- Babylon area. > The blowing process has changed very little since then. 12 Flat Glass Blown sheet 13 15th century Lead Crystal Glass: During the 15th century in Venice, the first clear glass called cristallo was invented. In 1675, glassmaker George Ravenscroft invented lead crystal glass by adding lead oxide to Venetian glass. 14 16th century Sheet Glass: Larger sheets of glass were made by blowing large cylinders which were cut open and flattened, then cut into panes 19th century Sheet Glass: The first advances in automating glass manufacturing were patented in 1848 by Henry Bessemer, an English engineer. -

Review 2009/2010

Review 2009/2010 Review 2009/10 Contents 3 Introduction from the Director 4 Extending and Broadening Audiences 8 Developing the Collection 12 Increasing Understanding of Portraiture and the Collection 16 Maximising Financial Resources 20 Improving Services 21 Developing Staff 22 Acquisitions 30 Financial Review 32 Supporters 35 Exhibitions and Displays Inside front cover Gallery Main Entrance Inside back cover Francis Alÿs: Fabiola display ‘The growing engagement with our programmes – whether new commissioned portraits or exhibitions, national and digital developments, or research and learning – gives me great confidence in the Gallery’s future development.’ Professor Sir David Cannadine, Chairman, Trustees of the National Portrait Gallery 3 Introduction Board of Trustees 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2010 from the Director Professor Sir David Cannadine, FBA, FRSL Chairman The Rt Hon. Baroness Whatever the continuing difficulties for the economy and Royall of Blaisdon (ex-officio) Lord President of the Council the country during the past year, the Gallery attracted a (until June 2009) growing audience, with record numbers to the BP Portrait Zeinab Badawi Award and over 250,000 visitors seeing the Taylor Wessing Professor Dame Carol Black Photographic Prize . All the year’s exhibitions – from Gay Icons (from March 2010) to Beatles to Bowie , The Indian Portrait , The Singh Twins Sir Nicholas Blake and Steve McQueen’s Queen and Country – successfully Dr Rosalind Blakesley demonstrated the connections between portraits and (from March 2010) individuals with fascinating and inspiring stories. Dr Augustus Casely-Hayford The Marchioness of Douro The launch of the National Portrait Gallery/BT Road to 2012 Dame Amelia Chilcott Fawcett, DBE was indicative of the Gallery’s determination to create new Deputy Chairman and Chair of the work and widen engagement with communities as part of Development Board the Cultural Olympiad. -

10 June 2011 Page 1 of 15

Radio 4 Listings for 4 – 10 June 2011 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 04 JUNE 2011 SAT 07:00 Today (b011msk2) Series 74 Morning news and current affairs with John Humphrys and SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b011jx96) Evan Davis. Episode 8 The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. 08:10 How effective are plans to curb provocative images seen Followed by Weather. by children? A satirical review of the week's news, chaired by Sandi 08:30 Lord Lamont and Alistair Darling on the economy. Toksvig. With Rory Bremner, Jeremy Hardy, Mark Steel and 08:44 The man who inspired the classic film The Battle of Fred Macaulay. SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b011mt39) Algiers. Ox Travels 08:49 Does London need its new Playboy club? SAT 12:57 Weather (b011jx9v) The Wrestler The latest weather forecast. SAT 09:00 Saturday Live (b011msk4) Ox Travels features original stories from twenty-five top travel Richard Coles with actor and director Richard Wilson, poet writers; this week we'll be featuring five of these stories. Susan Richardson, a woman who discovered her outwardly SAT 13:00 News (b011jx9x) respectable father was in fact a criminal gangster, and a man The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. Each of the stories takes as its theme a meeting life-changing, who kept a lion as a pet. There's an I Was There feature from a affecting, amusing by turn and together they transport readers man who worked on the world's first international satellite TV into a brilliant, vivid atlas of encounters.