Gagging for It: Irony, Innuendo and the Politics of Subversion in Women's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2

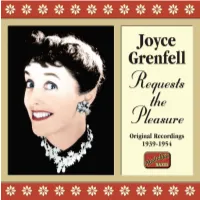

120860bk Joyce:MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2 1. I’m Going To See You Today 2:16 7. Mad About The Boy 5:08 12. The Music’s Message 3:05 16. Folk Song (A Song Of The Weather) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) (Noël Coward) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 1:29 With Richard Addinsell, piano With Mantovani & His Orchestra; Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Michael Flanders-Donald Swann) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9899-5 introduced by Noël Coward 13. Understanding Mother 3:10 With piano Recorded 17 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #4, (Joyce Grenfell) 17. Shirley’s Girl Friend 4:46 Towers of London, 1947–48 2. There Is Nothing New To Tell You 3:29 14. Three Brothers 2:57 (Joyce Grenfell) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 8. Children Of The Ritz 3:59 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 18. Hostess; Farewell 3:03 With Richard Addinsell, piano (Noël Coward) Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9900-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Recorded 3 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #12, 15. Palais Dancers 3:13 Towers of London, 1947–48 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) Tracks 12–18 from 3. Useful And Acceptable Gifts Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure (An Institute Lecture Demonstration) 3:05 9. We Must All Be Very Kind To Auntie Philips BBL 7004; recorded 1954 From The Little Revue Jessie 3:28 (Joyce Grenfell) (Noël Coward) All selections recorded in London • Tracks 5–9 previously unissued commercially HMV B 8930, 0EA 7852-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Transfers and Production: David Lennick • Digital Restoration:Alan Bunting Recorded 11 May 1939 (3:04) Noël Coward Programme #13, Original records from the collections of David Lennick and CBC Radio, Toronto 4. -

Wolverhampton & Black Country Cover

Wolverhampton Cover Online.qxp_Wolverhampton & Black Country Cover 30/03/2017 09:31 Page 1 LAURA MVULA - Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands INTERVIEW INSIDE WOLVERHAMPTON & BLACK COUNTRY WHAT’S ON WHAT’S COUNTRY BLACK & WOLVERHAMPTON Wolverhampton & Black Country ISSUE 376 APRIL 2017 ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD Onwolverhamptonwhatson.co.uk APRIL 2017 APRIL inside: Your 16-pagelist week by week listings guide ENGLISH presentsTOURING two classic OPERA works PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART in Wolverhampton StrictlyPASHA star KOVALEVbrings the romance of the rumba to the Midlands TWITTER @WHATSONWOLVES WOLVERHAMPTONWHATSON.CO.UK @WHATSONWOLVES TWITTER celebratingDISNEY 100 ON years ICE of magic at the Genting Arena TIM RICE AND ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER’S SMASH HIT MUSICAL AT THE GRAND Contents April Shrops.qxp_Layout 1 22/03/2017 20:10 Page 1 Birmingham@WHATSONBRUM Wolverhampton @WHATSONWOLVES Shropshire @WHATSONSHROPS staffordshire @WHATSONSTAFFS Worcestershire @WHATSONWORCS warwickshire @WHATSONWARWICKS Contents April Wolves.qxp_Layout 1 22/03/2017 21:16 Page 2 April 2017 Contents Russell Brand - contemplates the responsibilities of parenting at Victoria Hall, Stoke more on page 25 Laura Whitmore New Model Army La Cage aux Folles the list stars in brand new thriller at Yorkshire rock band bring John Partridge talks about his Your 16-page Shrewsbury’s Theatre Severn Winter to Bilston role in the hit West End musical week by week listings guide Interview page 8 page 17 Interview page 26 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 16. Music 24. Comedy 28. -

The Blue Review Literature Drama Art Music

Volume I Number III JULY 1913 One Shilling Net THE BLUE REVIEW LITERATURE DRAMA ART MUSIC CONTENTS Poetry Rupert Brooke, W.H.Davies, Iolo Aneurin Williams Sister Barbara Gilbert Cannan Daibutsu Yone Noguchi Mr. Bennett, Stendhal and the ModeRN Novel John Middleton Murry Ariadne in Naxos Edward J. Dent Epilogue III : Bains Turcs Katherine Mansfield CHRONICLES OF THE MONTH The Theatre (Masefield and Marie Lloyd), Gilbert Cannan ; The Novels (Security and Adventure), Hugh Walpole : General Literature (Irish Plays and Playwrights), Frank Swinnerton; German Books (Thomas Mann), D. H. Lawrence; Italian Books, Sydney Waterlow; Music (Elgar, Beethoven, Debussy), W, Denis Browne; The Galleries (Gino Severini), O. Raymond Drey. MARTIN SECKER PUBLISHER NUMBER FIVE JOHN STREET ADELPHI The Imprint June 17th, 1913 REPRODUCTIONS IN PHOTOGRAVURE PIONEERS OF PHOTOGRAVURE : By DONALD CAMERON-SWAN, F.R.P.S. PLEA FOR REFORM OF PRINTING: By TYPOCLASTES OLD BOOKS & THEIR PRINTERS: By I. ARTHUR HILL EDWARD ARBER, F.S.A. : By T. EDWARDS JONES THE PLAIN DEALER: VI. By EVERARD MEYNELL DECORATION & ITS USES: VI. By EDWARD JOHNSTON THE BOOK PRETENTIOUS AND OTHER REVIEWS: By J. H. MASON THE HODGMAN PRESS: By DANIEL T. POWELL PRINTING & PATENTS : By GEO. H. RAYNER, R.P.A. PRINTERS' DEVICES: By the Rev.T. F. DIBDIN. PART VI. REVIEWS, NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE. Price One Shilling net Offices: 11 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.G. JULY CONTENTS Page Post Georgian By X. Marcel Boulestin Frontispiece Love By Rupert Brooke 149 The Busy Heart By Rupert Brooke 150 Love's Youth By W. H. Davies 151 When We are Old, are Old By Iolo Aneurin Williams 152 Sister Barbara By Gilbert Cannan 153 Daibutsu By Yone Noguchi 160 Mr. -

JUNE 2020 E H T TMONRTHLY PUBELICATIONA of the SPRESBYTEURIAN CHRURCH of Y WALES the Centre of His Will Is Our Only Safety

JUNE 2020 e h t TMONRTHLY PUBELICATIONA OF THE SPRESBYTEURIAN CHRURCH OF Y WALES The Centre Of His Will Is Our Only Safety For ten weeks the public has been taking part in an act of and replaced by a similar annual event. Hopefully the vital communal appreciation for the NHS at 8pm on Thursday contribution of hospital staff and care home workers will evenings. Now the initiator of the idea, Dutch national, not be forgotten once the Covid-19 crisis ends, and that Annemarie Plas who lives in south London has suggested Government and the public will ensure that key workers that the weekly Clap for Our Carers should be concluded, and carers are recognised appropriately. A few weeks ago, Jimmy Cowley, a resident of the small hamlet of Burry Green, Gower had the wonderful idea to create a ‘thank-you’ tribute to those working in the NHS. He moved the now familiar icon into the green that faces Bethesda Presbyterian Church of Wales. As Eleanor Jenkins, Secretary of the two-hundred year old Burry Green Chapel, and Editor of the Burry Green Magazine observed, ‘you can’t make the message out when you drive past – it only becomes clear when seen from above.’ It reminded her (strangely!) of Corrie ten Boom, the brave Dutch lady and her sister Betsie who hid Jewish people during the war and were imprisoned by the Nazis. Triumphantly, she flipped the kitchen and ran down to join was a jagged piece of metal, ten After the war during Corrie’s cloth over and revealed an her. -

Download (3104Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/59427 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. THESIS INTRODUCTION The picture of themselves which the Victorians have handed down to us is of a people who valued morality and respectability, and, perhaps, valued the appearance of it as much as the reality. Perhaps the pursuit of the latter furthered the achievement of the former. They also valued the technological achievements and the revolution in mobility that they witnessed and substantially brought about. Not least did they value the imperial power, formal and informal, that they came to wield over vast tracts of the globe. The intention of the following study is to take these three broad themes which, in the national consciousness, are synonymous with the Victorian age, and examine their applicability to the contemporary theatre, its practitioners, and its audiences. Any capacity to undertake such an investigation rests on the reading for a Bachelor’s degree in History at Warwick, obtained when the University was still abuilding, and an innate if undisciplined attachment to things theatrical, fostered by an elder brother and sister. Such an attachment, to those who share it, will require no elaboration. My special interest will lie in observing how a given theme operated at a particular or local level. -

Hackney Archives - History Articles in Hackney Today by Subject

Hackney Archives - History Articles in Hackney Today by Subject These articles are published every fortnight in Hackney Today newspaper. They are usually on p.25. They can be downloaded from the Hackney Council website at http://www.hackney.gov.uk/w-hackneytoday.htm. Articles prior to no.158 are not available online. Issue Publication Subject Topic no. date 207 11.05.09 125-130 Shoreditch High Street Architecture: Business 303 25.03.13 4% Industrial Dwellings Company Social Care: Jewish Housing 357 22.06.15 50 years of Hackney Archives Research 183 12.05.08 85 Broadway in Postcards Research Methods 146 06.11.06 Abney Park Cemetery Open Spaces 312 12.08.13 Abney Park Cemetery Registers Local History: Records 236 19.07.10 Abney Park chapel Architecture: Ecclesiastical 349 23.02.15 Activating the Archive Local Activism: Publications 212 20.07.09 Air Flight in Hackney Leisure: Air 158 07.05.07 Alfred Braddock, Photographer Business: Photography 347 26.01.15 Allen's Estate, Bethune Road Architecture: Domestic 288 13.08.12 Amateur sport in Hackney Leisure: Sport 227 08.03.10 Anna Letitia Barbauld, 1743-1825 Literature: Poet 216 21.09.09 Anna Sewell, 1820-1878 Literature: Novelist 294 05.11.12 Anti-Racism March Anti-Racism 366 02.11.15 Anti-University of East London Radicalism: 1960s 265 03.10.11 Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Females, 1851 Social Care 252 21.03.11 Ayah's Home: 1857-1940s Social Care: Immigrants 208 25.05.09 Barber's Barn 1: John Okey, 1650s Commonwealth and Restoration 209 08.06.09 Barber's Barn 2: 16th to early 19th Century Architecture: -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Can Radio Peace?

RADIO PICTORIAL, November 5,1937; No. 199. PROGRAMME Registered at the Q.P.O. as a Newspaper November 7- 13 LUXEMBOURG : LYON NORMANDY :PARI TOULOUSE : ATHLON EVERY FRIDAY CAN RADIO BRING WORLD PEACE? MY RADIO THRILLS By Florence Desmond IN TOWN TO -NIGHT AGAIN JACK HYLTON ND HIS BAND By Edgar Jackson ELIZABETH CRAIG ORDON LITTLE PAT TAYLOR "AUNTIE MURIEL" 1100 CASH PRIZES FOR LISTENE (No Entrance F RADIO PICTORIAL November 5,1937 MODELS FROM SPECIAL 114'6 OFFER of reconditioned PIANOS BOYD Here isa wonderful opportunity to secure a piano reconditioned by our own factory and perfect in every detail PIANOS at a real Bargain price.Every model represents amazing value and is avail- able on the same Hire Purchase Terms as apply to our new pianos.Com- acre stoo te test otime plete Bargain list sent post free: PER moNTH Thirty. .Forty. Fifty years old and still giving as CRAVEN - 9/- good performance and as great pleasure as the day they I0/- were made !That is the proud record of many a NEIGHBOUR BOYD Piano.And that is the type of piano that you HASTINGS - II /- need in your home. LOCKE - II /- A piano that will stand up to hard usage when the SCHRODER II /- children first begin their music lessons, and for many, BANSALL - II /- many years after.A piano with a perfect tone and a SHERBOURNE II /- perfect touch that will charm and satisfy the keenest MUNT - II /- critic.A piano, in fact, that will be the proud possession WESTON I 2/- of yourself, your children and your children's children. -

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions by Ned Hémard

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard From “Men in Tights” to “Men in Krewes” Perhaps the most famous “man in tights” was Jules Léotard, a French acrobat who became the rage of London. Born in France in 1842, he was master of the flying trapeze act. Trained by his father, a Toulouse gymnastics instructor and swimming pool owner, he learned by practicing over the water. After passing his law exams, Léotard gave up a legal career for one on the trapeze. His first appearance in London was at the Alhambra in May of 1861. Two months later, at the Ashburnham Pavilion, Cremorne Gardens, Chelsea, the ace aerialist did his act on five trapezes - turning somersaults between each one. He returned again to London in 1866 and 1868, performing primarily in music halls and pleasure gardens, where he gained great popularity. Jules Léotard, more confident than daring, in his tights Jules Léotard’s success and notoriety brought about two things: “Leotards” became a new word for tights, and a man named George Leybourne wrote a popular British music hall song in 1867, The Flying Trapeze. We know the song as The (Daring Young) Man On The Flying Trapeze, a song that played a significant part in the 1934 Academy Award winning movie “It Happened One Night”, starring Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert. The Daring Young Man On The Flying Trapeze (illustrated sheet music cover page) Leybourne (March 17, 1842 - September 15, 1884), whose real name was Joe Saunders, originated for London music halls the role of “Champagne Charlie”, a high-rolling “swell” who was seen only in the most fashionable places. -

Howard Glover's Life and Career

Howard Glover’s Life and Career Russell Burdekin, July 2019, updated September 2021 (This note was originally part of the preparation for a paper given at the Music in Nineteenth Century Britain Conference, Canterbury Christ Church University, July 5, 2019. See http://englishromanticopera.org/operas/Ruy_Blas/Howard_Glover_Ruy_Blas- harbinger_of_English_Romantic_Opera_demise.pdf ) This note was revised in September 2021 thanks to an email from David Gurney pointing me to Augustus William Gurney’s Memoir of Archer Thompson Gurney, which provided background on Glover’s early life as well as a summary of his character. A few other details have also been amended or added. William Howard Glover was born on 6 June 1819 in London, the second son of Julia Glover one of the best known actresses of the first half of the 19th century. Who his father was is less certain. By the end of 1817, Julia was living apart from her husband, Samuel.1 However, she was on very close terms with the American actor, playwright and author John Howard Payne, who was then living in London.2 The inclusion of Howard as Glover’s middle name and John rather than Samuel being written on the baptism record3 would strongly suggest that Payne was the father, although no definitive evidence has been found. Glover studied the violin with William Wagstaff, leader of the Lyceum Opera orchestra, and joined that band at the age of fifteen. By the age of sixteen had a dramatic scena performed at a Society of British Musicians concert.4 He continued his studies for some years in Italy, Germany and France (Illustrated Times 2 Sep. -

Drag King Camp: a New Conception of the Feminine

DRAG KING CAMP: A NEW CONCEPTION OF THE FEMININE By ANDRYN ARITHSON B.A. University of Colorado, 2005 April 23, 2013 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Theatre & Dance 2013 This thesis entitled: Drag King Camp: a New Conception of the Feminine written by Andryn Arithson has been approved by the Department of Theatre & Dance ________________________________________________ Bud Coleman, Committee Chair ________________________________________________ Erika Randall, Committee Member ________________________________________________ Emmanuel David, Committee Member Date_______________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Arithson iii ABSTRACT Arithson, Andryn (M.A., Theatre) Drag Kings: A New Conception of the Feminine Thesis directed by Associate Professor Bud Coleman This thesis is an exploration of drag king performance through the lens of third wave feminism and Camp performance mechanisms. The term drag king refers to any person, usually female, that is making a performance of masculinity using costume, makeup and gesture. Camp is defined as an ever-changing system of humor and queer parody that works to subvert hegemonic cultural structures in an effort to gain queer visibility. Drag king Camp is posited as a theatrical mechanism that works to reveal maleness and masculinity as a performative act, therefore destabilizing the gender binary, and simultaneously revealing alternative conceptions of femininity. Drag king performance will be theorized in five sections. -

Geology and London's Victorian Cemeteries

Geology and London’s Victorian Cemeteries Dr. David Cook Aldersbrook Geological Society 1 Contents Part 1: Introduction Page 3 Part 2: Victorian Cemeteries Page 5 Part 3: The Rocks Page 7 A quick guide to the geology of the stones used in cemeteries Part 4: The Cemeteries Page 12 Abney Park Brompton City of London East Finchley Hampstead Highgate Islington and St. Pancras Kensal Green Nunhead Tower Hamlets West Norwood Part 5: Appendix – Page 29 Notes on other cemeteries (Ladywell and Brockley, Plumstead and Charlton) Further Information (websites, publications, friends groups) Postscript 2 Geology and London’s Victorian Cemeteries Part 1: Introduction London is a huge modern city - with congested roads, crowded shopping areas and bleak industrial estates. However, it is also a city well-served by open spaces. There are numerous small parks which provide relief retreat from city life, while areas such as Richmond Park and Riverside, Hyde Park, Hampstead Heath, Epping Forest and Wimbledon Common are real recreational treasures. Although not so obviously popular, many of our cemeteries and churchyards provide a much overlooked such amenity. Many of those established in Victorian times were designed to be used as places of recreation by the public as well as places of burial. Many are still in use and remain beautiful and interesting places for quiet walks. Some, on ceasing active use for burials, have been developed as wildlife sanctuaries and community parks. As is the case with parklands, there are some especially splendid cemeteries in the capital which stand out from the rest. I would personally recommend the City of London, Islington and St.