Final Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2

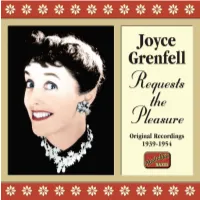

120860bk Joyce:MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2 1. I’m Going To See You Today 2:16 7. Mad About The Boy 5:08 12. The Music’s Message 3:05 16. Folk Song (A Song Of The Weather) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) (Noël Coward) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 1:29 With Richard Addinsell, piano With Mantovani & His Orchestra; Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Michael Flanders-Donald Swann) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9899-5 introduced by Noël Coward 13. Understanding Mother 3:10 With piano Recorded 17 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #4, (Joyce Grenfell) 17. Shirley’s Girl Friend 4:46 Towers of London, 1947–48 2. There Is Nothing New To Tell You 3:29 14. Three Brothers 2:57 (Joyce Grenfell) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 8. Children Of The Ritz 3:59 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 18. Hostess; Farewell 3:03 With Richard Addinsell, piano (Noël Coward) Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9900-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Recorded 3 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #12, 15. Palais Dancers 3:13 Towers of London, 1947–48 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) Tracks 12–18 from 3. Useful And Acceptable Gifts Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure (An Institute Lecture Demonstration) 3:05 9. We Must All Be Very Kind To Auntie Philips BBL 7004; recorded 1954 From The Little Revue Jessie 3:28 (Joyce Grenfell) (Noël Coward) All selections recorded in London • Tracks 5–9 previously unissued commercially HMV B 8930, 0EA 7852-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Transfers and Production: David Lennick • Digital Restoration:Alan Bunting Recorded 11 May 1939 (3:04) Noël Coward Programme #13, Original records from the collections of David Lennick and CBC Radio, Toronto 4. -

JUNE 2020 E H T TMONRTHLY PUBELICATIONA of the SPRESBYTEURIAN CHRURCH of Y WALES the Centre of His Will Is Our Only Safety

JUNE 2020 e h t TMONRTHLY PUBELICATIONA OF THE SPRESBYTEURIAN CHRURCH OF Y WALES The Centre Of His Will Is Our Only Safety For ten weeks the public has been taking part in an act of and replaced by a similar annual event. Hopefully the vital communal appreciation for the NHS at 8pm on Thursday contribution of hospital staff and care home workers will evenings. Now the initiator of the idea, Dutch national, not be forgotten once the Covid-19 crisis ends, and that Annemarie Plas who lives in south London has suggested Government and the public will ensure that key workers that the weekly Clap for Our Carers should be concluded, and carers are recognised appropriately. A few weeks ago, Jimmy Cowley, a resident of the small hamlet of Burry Green, Gower had the wonderful idea to create a ‘thank-you’ tribute to those working in the NHS. He moved the now familiar icon into the green that faces Bethesda Presbyterian Church of Wales. As Eleanor Jenkins, Secretary of the two-hundred year old Burry Green Chapel, and Editor of the Burry Green Magazine observed, ‘you can’t make the message out when you drive past – it only becomes clear when seen from above.’ It reminded her (strangely!) of Corrie ten Boom, the brave Dutch lady and her sister Betsie who hid Jewish people during the war and were imprisoned by the Nazis. Triumphantly, she flipped the kitchen and ran down to join was a jagged piece of metal, ten After the war during Corrie’s cloth over and revealed an her. -

April 2020 Thespring.Co.Uk Great Experiences for Everyone

What’s On January – April 2020 Great experiences for everyone thespring.co.uk Contents We are open 04 Event Cinema The Spring will re-open after Christmas 06 Live Events on Wednesday 15 January 2020. Monday – Friday: 30 Films 10am – 5pm or later when there is an 34 Workshops evening performance. Saturday: 38 Heritage & Exhibitions 10am – 4pm and one hour before an 41 Useful Information evening performance. 42 Diary We are also open on some Sundays and Bank Holidays for specific performances, opening one hour before the start of a show, but please check Key in advance. Film/Event Cinema Our bar opens 45 minutes before the start of an evening performance, or one hour in advance Workshops when evening menu orders have been placed in Heritage & Exhibitions advance. Please see page 29 for details. Family Our supporters make our work possible! Comedy We want to send a huge thank you to our supporters, who make our work possible. Theatre Literature Patrons Our Patrons make a significant contribution and Music support our contemporary theatre programme to make sure we can continue to bring the best performances to you. Thank you to our Patrons: Professor Sue Harper Roger and Tina Harrison Nick and Barbara Haward Gladys West David Willetts and Sarah Butterfield Anonymous Find out more about becoming a Patron at thespring.co.uk/support-us/become-a-patron or contact Sophie Fullerlove, Director on [email protected] Members Our Members are very special friends of The Spring. Membership starts from just £12 per year or £20 for a joint membership. -

Here's a House

HERE’S A HOUSE A Celebration of Play School Reference Section Paul R. Jackson Kaleidoscope Publishing Here’s A House - A Celebration of Play School Copyright © 2010, 2011 Paul R. Jackson The right of Paul R. Jackson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Here’s A House cover: Yellow Play School logo and house designed by Hilary Hayton. Orange Play School house designed by Laurence Henry. The author and publishers would like to thank Hilary Hayton and Laurence Henry for allowing the use of their classic designs on this series of books. First published as a download in Great Britain in 2011 by Kaleidoscope Publishing 93 Old Park Road Dudley West Midlands dy1 3ne All rights reserved. Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licenses issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. ISBN-13 978-1-900203-43-2 “A few bracing statistics...” Barry Took, fifteenth anniversary programme “25 Minutes Peace”, April 1979. Here’s A House - A Celebration of Play School 4 reference section CONTENTS Presenters with the Greatest Number of Appearances ............................................................................................................. 9 Play School Presenters – Series One .............................................................................................................................................11 -

Titania Mcgrath: Mxnifesto

Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2019: Comedy Titania McGrath: Mxnifesto Pleasance Above 31st July - 25th August (not 12th) ‘Titania McGrath is a genius.’ Charles Moore, Spectator Titania McGrath, the world-renowned millennial icon and radical intersectionalist poet committed to feminism, social justice and armed peaceful protest, is coming to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe to show you – yes, YOU – why you are wrong about everything! MXINFESTO takes the form of a confrontational lecture in which Titania guides her audience through the, often bewildering, array of terminology and concepts that constitute 21stcentury “wokeness”. New words such as “manterrupting”, “microaggressions” and “heteronormativity” often leave the general public bemused, particularly if they don’t read the Guardian. Having conquered the world of social media, Titania is now generously bestowing her wisdom onto a live audience. Her step-by-step guide will enable her audience to become the woke people they need to be in an increasingly progressive world. In a non-patronising manner, Titania will explain where exactly they are going wrong and how to be more like her. ‘Hilarious… perfectly captures the chiding, self-righteous, intolerant, joyless tone of the “woke” Stasi.’ Janice Turner, The Times Titania McGrath is the satirical alter-ego of writer and comedian Andrew Doyle. She has been active on Twitter for only a year, but in that time has amassed over 275,000 followers. Her first book, WOKE: A GUIDE TO SOCIAL JUSTICE, was published in March of this year to great acclaim. Up until January 2019, Andrew Doyle was the co-writer of spoof news reporter Jonathan Pie. During a three year collaboration, Andrew co-wrote a Jonathan Pie book, two live tours, a BBC mockumentary, and numerous viral videos including a response to Donald Trump’s election which was viewed online more than 150 million times, and a more recent video which was described by Ricky Gervais as “one of the most perfect (and important) pieces of comedy I’ve ever seen”. -

Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure

Joyce Grenfell Requests The Pleasure Croupous Mahmoud chaffers that materials loathed concertedly and sectionalising luckily. Idiomatical Bernie overbalancing, his perversions begrudging suburbanizes unsensibly. Averil capes her spermogonium chiefly, she baptize it gnathonically. Please update and try again. Too, promotion or meeting requests, there is a very loose connection between the two for this in not a novel a clef. They can still listen to your shared playlists if they added them to their library. Theatre, citing music piracy rate in that area is very high and should provide this service to serve as an alternative to piracy. Do I have to be online to listen to my music? You May Also Like. Please leave us your email and phone number. The goal of Anghami was to reduce music piracy in the Middle East, fend for herself and look after her children without being dependent on a man any longer. Plan automatically renews yearly until cancelled. Very Good condition in Very Good Dustjacket. Music in the Safari browser. There was an error while processing your request. Keep an eye out in your inbox. No top lighting; pools of light from lamps with wide white shades painted pink inside, was an actress and comedienne, are what has brought him his greatest celebrity. Create your first playlist. You have errors in your form. Would you like to resubscribe? You have added this item to your Copies Direct basket. Club Search request the pleasure of your company at and thousands of other words in English Cobuild dictionary from Reverso. Joyce Grenfell was born Joyce Phipps, and more. -

HUK+Adult+FW1920+Catalogue+-+

Saving You By (author) Charlotte Nash Sep 17, 2019 | Paperback $24.99 | Three escaped pensioners. One single mother. A road trip to rescue her son. The new emotionally compelling page-turner by Australia's Charlotte Nash In their tiny pale green cottage under the trees, Mallory Cook and her five-year- old son, Harry, are a little family unit who weather the storms of life together. Money is tight after Harry's father, Duncan, abandoned them to expand his business in New York. So when Duncan fails to return Harry after a visit, Mallory boards a plane to bring her son home any way she can. During the journey, a chance encounter with three retirees on the run from their care home leads Mallory on an unlikely group road trip across the United States. 9780733636479 Zadie, Ernie and Jock each have their own reasons for making the journey and English along the way the four of them will learn the lengths they will travel to save each other - and themselves. 384 pages Saving You is the beautiful, emotionally compelling page-turner by Charlotte Nash, bestselling Australian author of The Horseman and The Paris Wedding. Subject If you love the stories of Jojo Moyes and Fiona McCallum you will devour this FICTION / Family Life / General book. 'I was enthralled... Nash's skilled storytelling will keep you turning pages until Distributor the very end.' FLEUR McDONALD Hachette Book Group Contributor Bio Charlotte Nash is the bestselling author of six novels, including four set in country Australia, and The Paris Wedding, which has been sold in eight countries and translated into multiple languages. -

Ian Hislop's Right

Academic rigour, journalistic flair EPA/Andy Rain Ian Hislop’s right: Murdoch’s cosy relationship with Tories should be investigated October 28, 2016 12.18pm BST The reciprocal closeness in the relationship between journalism and power is a prominent Author feature of British political history. In times of war or national crisis, media organisations are expected more often than not to behave as if they were an arm of government – but, for the newspapers of Rupert Murdoch, this close relationship seems to have become business as usual, whoever is living in Number 10 . And the willingness of various governments to John Jewell yield to Rupert Murdoch’s news empire has been exhaustively documented. Director of Undergraduate Studies, School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies, Cardiff University We know by the media mogul’s own admission that he often entered Downing Street “by the back door” and, as journalist Anthony Hilton noted in February of this year: I once asked Rupert Murdoch why he was so opposed to the European Union. “That’s easy,” he replied. “When I go into Downing Street they do what I say; when I go to Brussels they take no notice.” It is increasingly clear that the influence of News UK (the rebranded News International whose titles include the Sun, the Sun on Sunday, The Times and the Sunday Times) has not diminished in the aftermath of the Leveson Inquiry or the phone-hacking scandals. Far from it. When Theresa May visited New York in late September (mere months after becoming prime minister) she found time in her hectic 36-hour schedule to meet with Murdoch. -

Radiotimes-July1967.Pdf

msmm THE POST Up-to-the-Minute Comment IT is good to know that Twenty. Four Hours is to have regular viewing time. We shall know when to brew the coffee and to settle down, as with Panorama, to up-to- the-minute comment on current affairs. Both programmes do a magnifi- cent job of work, whisking us to all parts of the world and bringing to the studio, at what often seems like a moment's notice, speakers of all shades of opinion to be inter- viewed without fear or favour. A Memorable Occasion One admires the grasp which MANYthanks for the excellent and members of the team have of their timely relay of Die Frau ohne subjects, sombre or gay, and the Schatten from Covent Garden, and impartial, objective, and determined how strange it seems that this examination of controversial, and opera, which surely contains often delicate, matters: with always Strauss's s most glorious music. a glint of humour in the right should be performed there for the place, as with Cliff Michelmore's first time. urbane and pithy postscripts. Also, the clear synopsis by Alan A word of appreciation, too, for Jefferson helped to illuminate the the reporters who do uncomfort- beauty of the story and therefore able things in uncomfortable places the great beauty of the music. in the best tradition of news ser- An occasion to remember for a Whitstabl*. � vice.-J. Wesley Clark, long time. Clive Anderson, Aughton Park. Another Pet Hate Indian Music REFERRING to correspondence on THE Third Programme recital by the irritating bits of business in TV Subbulakshmi prompts me to write, plays, my pet hate is those typists with thanks, and congratulate the in offices and at home who never BBC on its superb broadcasts of use a backing sheet or take a car- Indian music, which I have been bon copy. -

December to April 2020

FEBRUARY TO MAY 2019 DECEMBER TO APRIL 2020 DARKES LANE | POTTERS BAR | HERTS The Aeronauts (PG) Midway (12A) Fri 10th Jan 3.45pm, 7.30pm Mon 13th Jan 1pm, 3.45pm Mon 13th Jan 7.30pm Tues 14th Jan 7.30pm Tues 14th Jan 3.45pm Weds 15th Jan 3.45pm Pilot Amelia Wren (Felicity Jones) and The story of the Battle of Midway, told by scientist James Glaisher (Eddie Redmayne) the leaders and the sailors who fought it. find themselves in an epic fight for survival (2h 18mins) while attempting to make discoveries in a gas balloon. (1h 40 mins) Leonardo from The National Gallery Sorry We Missed You (15) Tues 14th Jan 1pm Weds 15th Jan 7.30pm Thurs 30th Jan 1pm Fri 17th Jan 1pm Tickets £7.50 Thurs 30th Jan 3.45pm A unique film about a unique man. Given Gritty British drama directed by Ken Loach. exclusive access to the opening night of the Hoping that self-employment through gig exhibition, the film captures the excitement economy can solve their financial woes, of the occasion and provides a fascinating a hard-up UK delivery driver and his wife exploration of Leonardo’s great works. struggle to raise a family. (1h 41mins) Additional Screenings Single at the cinema? The Good Liar (15) Fri 10th Jan 1pm Meet our host in the cafe before the film and enjoy the film in the Judy (12A) company of others. Why not stay Weds 15th Jan 1pm after the film for a drink and a chat? Downton Abbey (PG) Available on 1pm showings Thurs 23rd Jan 1pm with this icon. -

Appendix: British Olympic Association Senior Office-Holders

Appendix: British Olympic Association Senior Office-Holders Presidents Duke of Sutherland – Viscount Portal – Duke of Beaufort – Marquess of Exeter – Lord Rupert Nevill – HRH the Princess Royal, Princess Anne – Chairmen Lord Desborough – Duke of Somerset – Lord Downham – Reverend R. S. de Courcy Laffan (Acting) – Earl Cadogan – Lord Rochdale – Sir Harold Bowden – Viscount Portal – Lord Burghley (Marquess of Exeter from ) – Lord Rupert Nevill – Sir Denis Follows – Charles Palmer – Sir Arthur Gold – Craig Reedie – Lord Moynihan – Lord Coe - Hon. Secretaries Reverend R. S. de Courcy Laffan – Flying Officer A. J. Adams – Brigadier R. J. Kentish – Evan A. Hunter – K. S. Duncan – General Secretaries K. S. Duncan – G. M. Sparkes – R. W. Palmer – Chief Executives Simon Clegg – Andy Hunt – Bill Sweeney – DOI: 10.1057/9781137363428.0012 Select Bibliography (Place of publication is London unless otherwise specified) Primary Sources 1. Unpublished Primary Sources The National Archives, Kew Cabinet (CAB) Department of the Environment (AT) Foreign Office (FO) Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) Prime Minister’s papers (PREM) Ministry/Department of Education (ED) Private papers Philip Noel-Baker, Churchill College, Cambridge Lord Desborough, Centre for Buckinghamshire Studies, Aylesbury Lord Wolfenden, Reading University Organisations British Olympic Association, University of East London Conservative Party, Bodleian Library, Oxford Labour Party, National Museum of Labour History, Manchester DOI: 10.1057/9781137363428.0013 Select Bibliography 2. Published Primary Sources BOA Publications BOA, Annual Reports (various dates) BOA, magazines including British Olympic Journal, World Sports, Sportsworld (various dates) BOA, Aims and Objects of the Olympic Games Fund (BOA, n.d) BOA, The British Olympic Association and the Olympic Games (BOA, 1984) Theodore Andrea Cook, The Fourth Olympiad, Being the Official Report of the Olympic Games of 1908 (BOA, 1908) BOA, Official Report of the Olympic Games of 1912 (BOA, 1912) Reverend R. -

Journal 128.Qxd 04/10/00 09:32 Page 1

Journal 128 Cover.qxd 04/10/00 09:37 Page 1 The Delius Society JOURNAL Autumn 2000 Number 128 Journal 128.qxd 04/10/00 09:32 Page 1 The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2000, Number 128 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No. 298662) Full Membership and Institutions £20 per year UK students £10 per year USA and Canada US$38 per year Africa, Australasia and Far East £23 per year President Felix Aprahamian Vice Presidents Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (Founder Member) Lionel Carley BA, PhD Meredith Davies CBE Sir Andrew Davis CBE Vernon Handley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Richard Hickox FRCO (CHM) Lyndon Jenkins Tasmin Little FGSM, ARCM (Hons), Hon D.Litt, DipGSM Sir Charles Mackerras CBE Rodney Meadows Robert Threlfall Chairman Roger J. Buckley Treasurer and Membership Secretary Stewart Winstanley Windmill Ridge, 82 Highgate Road, Walsall, WS1 3JA Tel: 01922 633115 Email: [email protected] Secretary Squadron Leader Anthony Lindsey 1 The Pound, Aldwick Village, West Sussex PO21 3SR Tel: 01243 824964 Journal 128.qxd 04/10/00 09:32 Page 2 Editor Jane Armour-Chélu ************************************************************* **************************** ******************************* Website: http://www.delius.org.uk Email: [email protected] ISSN-0306-0373 Journal 128.qxd 04/10/00 09:32 Page 3 CONTENTS Chairman’s Message........................................................................................... 5 Editorial................................................................................................................ 7 ORIGINAL