The Italian Actress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jovanotti È Un Personaggio Colorato, Vitale, Prezioso Di Spunti E Sollecitazioni Anche Per Chi Non Dovesse Immedesimarsi Del Tutto Nel Suo Linguaggio

5 Prefazione L’idea della Zanichelli di affidare un robusto Dizionario del Pop-Rock a due dei no- stri più appassionati e colti critici musicali, Enzo Gentile e Alberto Tonti, ripercor- rendo decenni e decenni di storia della musica leggera nelle sue varie forme ed evo- luzioni, è un segnale importante per diversi motivi. Primo fra tutti quello di ferma- re una memoria storica che ci aiuta a comprendere l’evoluzione della società dal do- poguerra ad oggi. Sì, perché la Musica è la colonna sonora del tempo, degli umori degli anni, degli ideali di un periodo, della malinconia, degli entusiasmi o della rab- bia della società nel suo procedere. Voglio dire che si può perfettamente compren- dere lo stato d’animo di un popolo attraverso la colonna sonora che lo sta accom- pagnando in quel preciso momento storico. La Musica, dalla metà degli anni ’50 in poi, attraverso straordinari artisti ha suggerito mode, ha capovolto comportamen- ti. È stata la bandiera, grazie a molti brani, di lotte politiche, di battaglie civili, di poesie di protesta, di confessioni dolenti ma anche di esaltazione collettiva. Blues, Soul, Pop, Rock, Techno e tanti altri stili, fino ad arrivare alle più interessanti ricer- che sonore che partono da Brian Eno fino a Sylvian, Fripp e Scott Walker, sono le spericolate mutazioni di un’arte in perenne trasformazione che ascolta le pulsazio- ni della vita che corre. Per questo credo che un dizionario serio del Pop-Rock sia stato non solo un atto culturale indispensabile, ma un risarcimento, grazie alla cul- tura dei due autori e dei loro sensibili collaboratori, per tanti artisti a torto consi- derati minori e qui finalmente rivalutati e segnalati per il loro talento non ricono- sciuto tempestivamente. -

Montana Kaimin, January 14, 1983 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 1-14-1983 Montana Kaimin, January 14, 1983 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, January 14, 1983" (1983). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 7436. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/7436 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Montana Friday, January 14,1983 Today and tomorrow, sunny and warm. High today 35, low tonight 20, high tomorrow 38. aiminMissoula, Mont. Vol. 85, No. 44 B ASUM constitution to be reviewed By Jerry Wright "Basically we're just chang KtteinRiporttf ing it (the constitution) to The Constitutional Review policy, making things more Board will present a revised dear and getting rid of ob ASUM Constitution to Central solete practices," said Firpo. Board later this month for For example, the current review and CB approval. The constitution provides for spring revisions have been made to elections to fill CB and ASUM update the constitution to re officer positions for the follow flect current policy and to clar ing fall, he said. -

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická Fakulta Katedra Muzikologie

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra muzikologie 0Hana Svěntá ETNICKÁ HUDBA VE FILMU 1Analýza filmové hudby snímků Poslední pokušení Krista a Babel ETHNIC MUSIC IN FILM Analysis of Music in Films The Last Temptation Of Christ and Babel Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Matěj Kratochvíl Olomouc 2009 1 Prohlašuji, že jsem svou bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla v ní veškerou literaturu a prameny, které jsem použila. V Olomouci, 30. dubna 2009 ………………………… 2 Poděkování Děkuji Mgr. Matěji Kratochvílovi za odborné vedení práce a za poskytnutí cenných rad a informací. Také děkuji Prof. Ivu Bláhovi za konzultaci k analýze filmové hudby. 3 OBSAH Úvod ………………………………………………………………….……..... 6 1. Stav bádání …………………………………………………….………... 8 2. Úvod do teorie a analýzy filmové hudby ……...………….…...…...11 2.1. Filmová hudba a její funkce………………………...….………. 11 2.2. Filmová hudba původní a archivní…………………...….…….. 13 2.3. Hudba k úvodním a závěrečným titulkům…………….………. 16 2.4. Hudební dramaturgie…………………………………….………..17 2.5. Stručný úvod do analýzy etnické filmové hudby…….………. 19 3. Přístupy k analýze filmové hudby ……………………….………… 20 4. Poslední pokušení Krista …………………………………….……… 28 4.1. Vznik filmu Poslední pokušení Krista ……………….……….. 29 4.2. Děj filmu Poslední pokušení Krista ……………….………….. 31 4.3. Tvůrčí osobnost režiséra Martina Scorseseho ……...…….…. 33 4.4. Hudebník a aktivista Peter Gabriel ………………………....… 37 4.5. Hudba k filmu Poslední pokušení Krista ……………….…….. 42 4.5.1. Spolupráce Scorseseho a Gabriela …………………….…... 42 4.5.2. Passion & Passion Sources ……………………………….… 44 4.5.3. Analýza hudby k filmu Poslední pokušení Krista ……..… 46 4.5.4. Analýza vybraných částí filmu Poslední pokušení Krista ……………………………….……………... 52 4.5.5. Zhodnocení …………………………………….…………….. 60 5. Babel ……………………………………………………….………….… 62 5.1. Vznik filmu Babel ……………………………………………... -

Shaking the Trees PDF Book

SHAKING THE TREES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Azra Tabassum | 74 pages | 25 Jun 2014 | Words Dance Publishing | 9780692232408 | English | United States Shaking the Trees PDF Book Oct 04, Daphne rated it did not like it. Upgrade Now. Sound Mix: Ultra Stereo. Saturday 10 October User Reviews. The characters in this movie not only talk of "shaking the tree," but much later return to the theme, to explain and discuss the movie's message. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. Tuesday 1 September A poignant look at the experience of first time loves, beautifully done by an emerging writer. Greatest-hits albums are a traditional way of buying time for artists between albums. Thursday 17 September Plot Summary. Wednesday 5 August Jul 18, Camille rated it really liked it Shelves: poetry. Friday 9 October To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Sunday 3 May In a scene between the young gambler and his grandfather, a fire crackles on the soundtrack so loudly we wonder if static has crept into the sound system. Wednesday 15 July Wednesday 29 April Games Without Frontiers Peter Gabriel. They kiss. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. Sunday 18 October Mix between prose and poetry, I found the prose bits more powerful and engaging. Changing your ways, changing those surrounding you Changing your ways, more than any man can do Open your heart, show him the anger and pain, so you heal Maybe he's looking for his womanly side, let him feel. Wednesday 1 July When they begin to ask for you to shape yourself around them, leave. -

Versity of California

Th DC D ar University of California. San Die~o / VolulIle .17. '\i 1IIllb('J' 7/ Thursday, October 11. J HH2 Sexual harassment in academia ., ~ ., By CANOLE \ '( "Why can't he keep his , I .",~ hands off me? I don't care if h /1 I "ays he likes his favonte .1v·- J female st udents. ~ "I've told hIm before that It bothers me. I can't study ~ I under thesc conditions. When I came hcre I thought I was I~j ,.- exp ted tou:;emymind to get " grades. not my body." -.4 -i Christine (not her real - name) is a UCSD student. She ,If Is also a vIctim of sexual / harassment. Onc of her \1 ,I profcssor'i ha~ persistently w' made advances towards her, / ' putting her in an emotional , ,• ',I' ,)r academIc maelstrom. ~. I ( . !.. he wants to know how to ~,~ . lj~:~ J' stop the hara ment without threatening her academic career, and how to get the word out, to stop future (~lIJ!-;t haras, ment of female tudents. -. , There i a growing need to ~ . educate and sen itize the '" - campus community so that faculty and T.A.s will realize -....... that, though their approach - , mIght be well intentioned, any '- ty pe of advance will put their tudent in a compromising ...... positIon. , - -:')... Early in the academic year, Chancellor Atkinson relea. ed -""--.- \ a lengthy letter addressed to --- g-raduate students. faculty and taff in which ::I <;mall in 'crt , tated that the admtnlstration has im oked a t mporary policy regarding sexual harassment.It wa. also noted that a COpy of this statement .' was on file. -

WLIR Playlist

I believe this complete list of WLIR/WDRE songs originally appeared on this site, but the full playlist is no longer available. https://wlir.fm/ It now only has the list of “Screamers and Shrieks” of the week—these were songs voted on by listeners as the best new song of the week. I’ve included the chronological list of Screamers and Shrieks after the full alphabetical playlist by artist. 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Can't Ignore The Train 10,000 Maniacs Eat For Two 10,000 Maniacs Headstrong 10,000 Maniacs Hey Jack Kerouac 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Non-Live version) 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Live) 10,000 Maniacs Peace Train 10,000 Maniacs These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10,000 Maniacs What's The Matter Here 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 12 Drummers Drumming We'll Be The First Ones 2 NU This Is Ponderous 3D Nearer 4 Of Us Drag My Bad Name Down 9 Ways To Win Close To You 999 High Energy Plan 999 Homicide A Bigger Splash I Don’t Believe A Word (Innocent Bystanders) A Certain Ratio Life's A Scream A Flock Of Seagulls Heartbeat Like A Drum A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran A Flock Of Seagulls It's Not Me Talking A Flock Of Seagulls Living In Heaven A Flock Of Seagulls Never Again (The Dancer) A Flock Of Seagulls Nightmares A Flock Of Seagulls Space Age Love Song A Flock Of Seagulls Telecommunication A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls What Am I Supposed To Do A Flock Of Seagulls Who's That Girl A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing A Popular History Of Signs The Ladderjack -

List by Song Title

Song Title Artists 4 AM Goapele 73 Jennifer Hanson 1969 Keith Stegall 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 3121 Prince 6-8-12 Brian McKnight #1 *** Nelly #1 Dee Jay Goody Goody #1 Fun Frankie J (Anesthesia) - Pulling Teeth Metallica (Another Song) All Over Again Justin Timberlake (At) The End (Of The Rainbow) Earl Grant (Baby) Hully Gully Olympics (The) (Da Le) Taleo Santana (Da Le) Yaleo Santana (Do The) Push And Pull, Part 1 Rufus Thomas (Don't Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again L.T.D. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 Nat King Cole (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash (Goin') Wild For You Baby Bonnie Raitt (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody WrongB.J. Thomas Song (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Otis Redding (I Don't Know Why) But I Do Clarence "Frogman" Henry (I Got) A Good 'Un John Lee Hooker (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations (The) (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons ** Sam Cooke (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! ** Shania Twain (I'm A) Stand By My Woman Man Ronnie Milsap (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkeys (The) (I'm Settin') Fancy Free Oak Ridge Boys (The) (It Must Have Been Ol') Santa Claus Harry Connick, Jr. -

Combined Song List

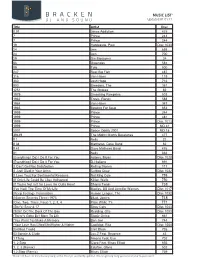

B R ACKEN MUSIC LIST* D J AND SOUND Updated 01.01.11 Title Artist Disc 0.01 Janes Addiction 425 7 Prince 243 7 Prince 244 19 Hardcastle, Paul Disc 1033 24 Jem 658 24 Jem 700 29 Gin Blossoms 34 86 Greenday 584 99 Toto 500 247 Reel Big Fish 487 316 Van Halen 119 360 Josh Hoge 716 900 Breeders, The 361 1251 The Strokes 82 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 503 1982 Travis, Randy 588 1984 Van Halen 347 1985 Bowling For Soup 653 1999 Prince 244 1999 Prince 481 1999 Prince Disc 1013 1999 Prince MD 41 2001 Space Oddity 2001 MD 18 39449 The Mighty Mighty Bosstones 477 # 1 Nelly 22 # 34 Matthews, Dave Band 62 # 41 Dave Mathews Band 476 #1 Nelly 664 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Adams, Bryan Disc 1028 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You DJ Italiano 691 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 117 (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew Disc 1032 (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole 755 (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells 750 (If You're Not in It for Love) I'm Outta Here! Shania Twain 738 (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Medley, Bill And Jennifer Warnes Disc 1017 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League, The Disc 1032 (Ninteen Seventy Three) 1973 Blunt, James 748 (One, Two, Three, Four) 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's 771 (She's) Sexy & 17 Stray Cats Disc 1043 (Sittin' On)The Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis Disc 1003 (There's Gotta Be) More To Life Stacie Orrico 661 (You Want To) Make A Memory Bon Jovi 744 (Your Love Has Lifted Me)Higher & Higher Coolidge, Rita Disc 1054 [Untitled Track] Clint Black 735 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z Feat. -

Explanations

Tagg: Music’s Meanings— Index 653 Index Explanations CONTENTS. This index contains: [1] proper names occurring in the main text and in the footnotes; [2] principal topics in main text and footnotes; [3] selected technical and theoretical terms; [4] other terms marked for indexing on at least three separate pages. The acknowledgements and reference appendix have not been indexed for this book. To find items not included in this index please use the e‐book version (PDF), obtainable via tagg.org/mmmsp/NonMusoInfo.htm. SYMBOLS. q = See another main entry; ! = See subentry under another main entry; = See also another main entry or other entries; ˆ = in relation to or as opposed to. Note that main entries referred to are always in THIS FONT, subentries in this font. EXAMPLES. [1] ‘q GUITAR’ under ACOUSTIC means See under GUITAR for page numbers relating to ACOUSTIC GUITAR. [2] ‘q MODE!maqām’ under ARAB means See the subentry MAQĀM un‐ der the main index entry MODE to find the pages where the modes of Arab music are men‐ tioned. [3] To find more page references to topics relating to ACCOMPANIMENT, See also un‐ der BACKGROUND (‘ BACKGROUND’). [4] The subentry ‘ˆ female’ under the main entry MALE means that the two concepts MALE and FEMALE are considered in relation to each other (on pp. 18, 86, 357, etc.) rather than separately. [5] ‘ˆ male q MALE ˆ FE‐ MALE’ under FEMALE means See the subentry ‘ˆ FEMALE’ under MALE for the same page references (pp. 18, 86, 357, etc.). ABBREVIATIONS. def. = definition; mus. = music[al]; repres. -

Peter Gabriel Släpper Remastrade Vinyl Versioner Av Sina 4 Första Album

2015-07-28 11:00 CEST Peter Gabriel släpper remastrade vinyl versioner av sina 4 första album On October 2nd Peter Gabriel’s first four self-titled solo albums are being made available on vinyl for the first time since 2002. Also being made available are the long out-of-print German vocal versions of Peter Gabriel’s third and fourth albums. The first three albums are affectionately known as Car, Scratch and Melt due to their iconic Hipgnosis designed covers. The fourth album was named Security for the American market on its initial release. All the albums have been Half-Speed Remastered and cut to lacquers at 45RPM, across two heavyweight 180g LPs to deliver maximum dynamic sound range. The vinyl was cut by Matt Colton at Alchemy Mastering, mastered by Tony Cousins at Metropolis and overseen by Peter’s main sound engineer Richard Chappell. The expertise and care that has gone into remastering these albums is incredible and consequently they have never sounded so good. The vinyl editions will be gatefold sleeves, utilising imagery from the initial first LP pressings, sourced and re-scanned from original artwork. Each English language album comes as a limited edition of 10,000 Worldwide (German versions limited to 3,000 Worldwide). All are individually numbered. Albums include download cards with a choice of digital download (Hi-Res 24- bit/96k or 16-bit/44.1k). These releases form the first wave of vinyl re-releases that will see all of Peter’s albums given the Half-Speed Remaster treatment over time. Further roll-out details to follow. -

Form and Style in the Music of U2 Christopher James Scott Endrinal

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Form and Style in the Music of U2 Christopher James Scott Endrinal Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC FORM AND STYLE IN THE MUSIC OF U2 By CHRISTOPHER JAMES SCOTT ENDRINAL A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Spring Semester, 2008 Copyright © 2008 Christopher J. S. Endrinal All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Christopher J. S. Endrinal, defended on 25 February 2008. Jane Piper Clendinning Professor Directing Dissertation James R. Mathes Committee Member Matthew R. Shaftel Committee Member Charles E. Brewer Outside Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above listed committee members. ii To Azucena and Dominic. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to extend my gratitude and appreciation to my advisor, Professor Jane Piper Clendinning. Her guidance and support during my entire tenure at Florida State have proven to be invaluable resources, for which I cannot thank her enough. I also extend my appreciation to Professor James Mathes (whose doctoral seminar provided the initial inspi- ration for this research) and to Professors Matthew Shaftel and Charles Brewer, for lending me their unique perspectives and insightful critiques. I would also like to thank the rest of the Music Theory faculty at Florida State. Their vast knowledge and constant encourage- ment helped keep me focused and motivated. -

The Art of Massage by David Lauterstein

The Art of Massage by David Lauterstein INSTRUCTIONS FOR THIS CE: The Art of Massage is a course meant to stimulate your imagination and inspire you and your massage/bodywork. We recommend not reading it straight through but rather reading just one or more sections each day and thinking about them. Let them resonate and affect your understanding and intuition. After you have done all the reading, to receive the certificate for completing the 3 hours of continuing education – do the exam, choosing the best answer for each question. There is also a required minimum 250-word essay, to help you integrate your own insights and excitements reflecting on what you have read, thought and felt. Both will be graded and require a score of 70% or more. Each essay will be individually graded and commented on by David Lauterstein. We hope that this process will enrich your work and life. 1 The Lauterstein-Conway Massage School and Clinic Table of Contents Acknowledgements 5 Preface 6 Accuracy 13 “Altared” States 15 A Poem About Massage 18 Believing in Touch 20 Body Questions 22 Breath 23 Destiny Made Visible 25 Diaphragms of Life 27 Don’t Lose the Music 30 Eternity 32 Evaluation as Act of Mercy 34 Facial Diaphragms 35 Galea Aponeurotica 37 God’s First Language 39 Growing New Arms 40 How the Radiologist Changed My Life 42 In Every Pause 43 Is Pain Your Friend? 45 I Saw the Angel 47 In Work We Know 49 Lifting off Your Head 50 Look at Me! 51 Loving Time 53 Massage at the Red Sea 54 Mind-Body Adhesion 56 2 The Lauterstein-Conway Massage School and Clinic