The Evolution of Housing on the Bendigo Goldfields: a Case for Serial Listings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 39TH EDITION 2011-12

THE BENDIGO TRUST Annual Report 39TH EDITION 2011-12 Bringing Bendigo’s history to life ... Annual Report 2011/12 1 2 The Bendigo Trust TABLE OF CONTENTS From the Chairman and the CEO 4 The Bendigo Trust in 2011/12 Central Deborah Gold Mine 8 Bendigo Tramways 10 Discovery Science & Technology Centre 13 Bendigo Joss House Temple 14 Bendigo Gas Works 14 Victoria Hill 15 Finance 16 Sales and Marketing 18 Acknowledgements 21 Trust Staff and Volunteers 22 Board of Directors 24 Financial Report 27 Annual Report 2011/12 3 FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Lloyd Cameron, All of the dedicated staff and volunteers at The Bendigo Chairman Trust recognise the importance of keeping Bendigo’s history alive and each play a crucial role in preserving it for future generations to enjoy. Before reviewing the major accomplishments and challenges for 2011/12, we would like to say a big "Thank You." The year to 30 June 2012 was a challenging congratulated for the succession of popular one. Continued economic uncertainty was exhibitions that in recent years have made a Tom Seddon, CEO the key driver of a poor Christmas season big difference to tourism across the city. nationally, something that we certainly experienced here in Bendigo. Despite this, the Unwanted Water, and lots of it Trust returned to a cash surplus for the year. The real unwelcome surprise of the year was 2011/12 also saw the completion of the the announcement by Unity Mining Ltd that $3.2 million tram depot overhaul project and it was pulling out of Bendigo. -

Tovvn and COUN1'r,Y PL1\NNING 130ARD

1952 VICTORIA SEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT 01<' THE TOvVN AND COUN1'R,Y PL1\NNING 130ARD FOI1 THE PERIOD lsr JULY, 1951, TO 30rH JUNE, 1~)52. PHESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 4 (3) OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLA},"NING ACT 1944. Appro:rima.te Cost of Repo,-1.-Preparat!on-not given. PrintJng (\l50 copieti), £225 ]. !'!! Jtutlt.ortt!): W. M. HOUSTON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 5.-[2s. 3d.].-6989/52. INDEX Page The Act-Suggested Amendments .. 5 Regulations under the Act 8 Planning Schemes-General 8 Details of Planning Schemes in Course of Preparation 9 Latrobe Valley Sub-Regional Planning Scheme 12 Abattoirs 12 Gas and Fuel Corporation 13 Outfall Sewer 13 Railway Crossings 13 Shire of Narracan-- Moe-Newborough Planning Scheme 14 Y allourn North Planning Scheme 14 Shire of Morwell- Morwell Planning Scheme 14 Herne's Oak Planning Scheme 15 Yinnar Planning Scheme 15 Boolarra Planning Scheme 16 Shire of Traralgon- Traralgon Planning Scheme 16 Tyers Planning Scheme 16 Eildon Sub-Regional Planning Scheme 17 Gelliondale Sub-Regional Planning Schenu• 17 Club Terrace Planning Scheme 17 Geelong and Di~triet Town Planning Scheme 18 Portland and DiHtriet Planning Scheme 18 Wangaratta Sub-Regional Planning Scheme 19 Bendigo and District Joint Planning Scheme 19 City of Coburg Planning Scheme .. 20 City of Sandringham Planning Seheme 20 City of Moorabbin Planning Scheme~Seetion 1 20 City of Prahran Plaml'ing Seheme 20 City of Camberwell Planning Scheme 21 Shire of Broadml'adows Planning Scheme 21 Shire of Tungamah (Cobmm) Planning Scheme No. 2 21 Shire of W odonga Planning Scheme 22 City of Shepparton Planning t::lcheme 22 Shire of W arragul Planning Seh<>liH' 22 Shire of Numurkah- Numurkah Planning Scheme 23 Katunga. -

VPRS 1078 ‐ Petitions and Addresses to the Governor

VPRS 1078 ‐ Petitions and Addresses to the Governor Petition Year Description No. 1 1854 Petition from Melbourne Chamber of Commerce re postage charge of 4/‐. 2 1854 Petition from Melbourne Chamber of Commerce re postage charge of 4/‐. 3 1856 Address from Ministers of Wesleyan Methodist Church 4 1856 Address from the Legislative Assembly 5 1856 Address from Municipal Council of Williamstown 6 1856 Address from the Legislative Council 7 1856 Address from the Legislative Council 8 1857 Address from Committee of Benevolent Asylum, Melbourne 9 1857 Address from Magistrates of Colony & City of Melbourne 10 1857 Address from Presbyterian Synod 11 1857 Address from Municipal Council, Castlemaine 12 1857 Address from Protestant Ministers, Castlemaine 13 1857 Adress from Local Court, Sandhurst 14 1857 Address from Ballarat District Road Board 15 1857 Address from Philosophical Institute of Victoria 16 1857 Address from University of Melbourne 17 1857 Address from Local Court of Ballarat 18 1857 Address from Magistrates, Clergy & Others of Albury 19 1857 Address from Geelong Mechanics Institute 20 1857 Address from Geelong Sea Bathing Company 21 1857 Address from Geelong Infirmary & Benevolent Asylum 22 1857 Address from Geelong Chamber of Commerce 23 1857 Address from Town Council of Geelong 24 1857 Address from Directors of Geelong & Melbourne Railway 25 1857 Petition from Inhabitants of Warrnambool 26 1857 Address from Geelong Orphan Asylum 27 1857 Address from United Church, Geelong 28 1857 Address from Justices of the Peace, Geelong 29 1857 -

North-West-Victoria-Historic-Mining-Plots-Dunolly

NORTH WEST VICTORIA HISTORIC MINING PLOTS (DUNOLLY, HEATHCOTE, MALDON AND RUSHWORTH) 1850-1980 Historic Notes David Bannear Heritage Victoria CONTENTS: Dunolly 3 Heathcote 48 Maldon 177 Rushworth 268 DUNOLLY GENERAL HISTORY PHASE ONE 1853/55: The Moliagul Police Camp had been down at the bottom end of Commissioners Gully near Burnt Creek from January 1853 until June 1855. This camp included a Sub Inspector, two Sergeants, a Corporal, six mounted and twelve-foot Constables, a Postmaster, Clerk and Tent Keeper. For a while this was the headquarters for the entire Mining District. 1 1853 Moliagul: Opened in 1853 along with Surface Gully. Their richness influenced the moving of the settlement from Commissioners Gully to where the township is now. 2 1853: Burnt Creek, the creek itself, was so-called before gold digging started, but Burnt Creek goldfield, situated about two miles south of Dunolly, started with the discovery of gold early in 1853, and at a rush later that year ... Between August and October 1853 the Commissioners’ Camp at Jones Creek was shifted to Burnt Creek, where there had been a rush ... By April 1854 there had been an increase in population at Burnt Creek, and there were 400 diggers there in July. Digging was going on in Quaker’s Gully and two large nuggets were found there in 1854, by October there were 900 on the rush, and the Bet Bet reef was discovered. By November 1854 the gold workings extended three miles from Bet Bet to Burnt Creek and a Commissioners’ Camp was started at Bet Bet, near where Grant’s hotel was later. -

Heritage Citation Report

HERITAGE CITATION REPORT Name Hawthorn Farm and Outbuildings Address 2406 Kyneton-Redesdale Road REDESDALE Grading 2008 Local Building Type Homestead Complex Assessment by Context Pty Ltd Recommended VHR No HI No PS Yes Heritage Protection Architectural Style Victorian Period (1851-1901) Vernacular Maker / Builder Unknown Integrity Altered History and Historical Context History of the Shire of Metcalfe Note: The following history is a series of excerpts from Twigg, K. and Jacobs, W (1994) Shire of Metcalfe Heritage Study Volume 1 Environmental History, Ballarat. The land around the former Shires of Strathfieldsaye and McIvor had a long history prior to the arrival of Europeans. The Jaara Jaara people are the original inhabitants of the area. Hawthorn Farm and Outbuildings 29-Dec-2009 03:24 PM Hermes No 33076 Place Citation Report Page 1 of 6 HERITAGE CITATION REPORT The area around Port Phillip was explored by Sir Thomas Mitchell, the Surveyor General of New South Wales, and a large party in 1836, on the homeward leg of a journey to Portland Bay. Impressed by what he perceived as the bounty of the land, Mitchell named the area Australia Felix. Less than a year after Mitchell's return to Sydney with glowing reports of the stocking capabilities of the land in the south, the first overlanders arrived in the district and soon thereafter laid claim to the rich basaltic plains of the Campaspe and Coliban Rivers. The pastoral occupation of the Shire was completed by 1843 and the process of shaping the landscape to fit the demands of white settlement, gathered pace. -

Liva 1 – the First Medieval Sámi Site with Rectangular Hearths in Murmansk Oblast (Russia)

Liva 1 – The First Medieval Sámi Site with Rectangular Hearths in Murmansk Oblast (Russia) Anton I. Murashkin & Evgeniy M. Kolpakov Anton I. Murashkin, Department of Archaeology, St Petersburg State University, Mendeleyevskaya linya 5, RU-199034 St Petersburg, Russia: [email protected], [email protected] Evgeniy M. Kolpakov, Department of Palaeolithic, Institute for the History of Material Culture, Russian Academy of Sciences, Dvortsovaya nab. 18, RU-191186 St Petersburg, Russia: [email protected] Abstract In 2017–2018, the Kola Archaeological Expedition of the Institute of the History of Material Culture (IHMC) RAS carried out excavations at the medieval site of Liva 1 (a hearth-row site) in the Kovdor District of Murmansk Oblast. Sites of this type are fairly well studied in the western part of Sapmi – the area inhabited by the Sámi – but until now they have not been known in Russia. The site was found by local residents in 2010. Some of the structures there were destroyed or damaged when searching for artefacts with a metal detector. A total of nine archaeological structures have been discovered (7 rectangular stone hearths, 1 mound, 1 large pit). Four hearths were excavated. They are of rectangular shape, varying in size from 2.0 x 1.15 to 2.5 x 1.7 metres. The fireplaces are lined with large stone blocks in one course, and the central part is filled with small stones in 2–3 layers. Animal bones, occasionally forming concentrations, were found near the hearths. Throughout the area of the settle- ment, numerous iron objects (tools or their fragments) and bronzes were collected including ornaments made in manufacturing centres of Old Rus’, Scandinavia and the Baltic countries. -

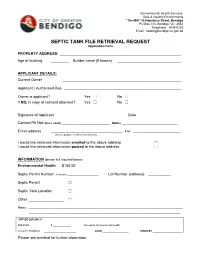

City-Of-Greater-Bendigo-File Retrieval Request Form July 2021.Pdf

Environmental Health Services, Safe & Healthy Environments “The Mill” 15 Hopetoun Street, Bendigo PO Box 733, Bendigo Vic 3552 Telephone: 5434 6333 Email: [email protected] SEPTIC TANK FILE RETRIEVAL REQUEST Application Form PROPERTY ADDRESS: ___________________________________________________________ Age of building _________ Builder name (If known) _______________________________ APPLICANT DETAILS: Current Owner __________________________________________________________ Applicant / Authorised Rep _________________________________________________________ Owner is applicant? Yes £ No £ If NO, is copy of consent attached? Yes £ No £ Signature of Applicant _________________________________ Date _____________________ Contact Ph Nos (Home / work) ________________________ (Mobile) ___________________________ Email address ___________________________________ Fax _______________________ (for the purpose of document delivery) I would like retrieved information emailed to the above address £ I would like retrieved information posted to the above address £ INFORMATION (please tick required boxes) Environmental Health $150.00 Septic Permit Number: (if known) _______________ Lot Number (address): ___________ Septic Permit £ Septic Tank Location £ Other: _________________ £ Notes: __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ “OFFICE USE ONLY” FEE PAID $ _____________ Receipt to: Environmental health: RECEIPT NUMBER _______________________ -

Modernism and Reindeer in the Bering Straits

More Things on Heaven and Earth: Modernism and Reindeer in the Bering Straits By Bathsheba Demuth Summer 2012 Bathsheba Demuth is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of California, Berkeley The Scene On a modern map, the shoulders of Eurasia and North America nearly touch at the Bering Strait, a 52-mile barrier between Old World and New. During the rolling period of ice ages known as the Pleistocene, the Pacific Ocean pulled back leaving the Chukchi Peninsula connected to Alaska’s Seward Peninsula by a wide, grassy plain. Two million years ago, the animal we call the reindeer emerged along this continental juncture.1 As glaciers spread, reindeer followed them southward; by 20,000 years ago, Rangifer tarandus had moved deep into Western Europe, forming the base of Neolithic hunters’ diets and appearing, antlers lowered in the fall rutting charge, on the walls of Lascaux.2 Reindeer, like our human ancestors who appeared a million and a half years after them, are products of the ice age. They are gangly, long-nosed, and knob-kneed, with a ruff of white fur around their deep chests, swooping antlers and nervous ears, and have the capacity to not just survive but thrive in million-strong herds despite the Arctic dark and cold. Like any animal living in the far north, reindeer – or caribou, as they are known in North America – must solve the problem of energy. With the sun gone for months of the year, the photosynthetic transfer of heat into palatable calories is minimal; plants are small, tough, often no more than the rock-like scrum of lichens. -

SCG Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation

Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation September 2019 spence-consulting.com Spence Consulting 2 Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation Analysis by Gavin Mahoney, September 2019 It’s been over 20 years since the historic Victorian Council amalgamations that saw the sacking of 1600 elected Councillors, the elimination of 210 Councils and the creation of 78 new Councils through an amalgamation process with each new entity being governed by State appointed Commissioners. The Borough of Queenscliffe went through the process unchanged and the Rural City of Benalla and the Shire of Mansfield after initially being amalgamated into the Shire of Delatite came into existence in 2002. A new City of Sunbury was proposed to be created from part of the City of Hume after the 2016 Council elections, but this was abandoned by the Victorian Government in October 2015. The amalgamation process and in particular the sacking of a democratically elected Council was referred to by some as revolutionary whilst regarded as a massacre by others. On the sacking of the Melbourne City Council, Cr Tim Costello, Mayor of St Kilda in 1993 said “ I personally think it’s a drastic and savage thing to sack a democratically elected Council. Before any such move is undertaken, there should be questions asked of what the real point of sacking them is”. Whilst Cr Liana Thompson Mayor of Port Melbourne at the time logically observed that “As an immutable principle, local government should be democratic like other forms of government and, therefore the State Government should not be able to dismiss any local Council without a ratepayers’ referendum. -

Aboriginal People on the Goldfields of Victoria, 1850-1870

Black Gold Aboriginal People on the Goldfields of Victoria, 1850-1870 Fred Cahir Black Gold Aboriginal People on the Goldfields of Victoria, 1850-1870 Fred Cahir Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 25 This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cahir, Fred. Title: Black gold : Aboriginal people on the goldfields of Victoria, 1850-1870 / Fred Cahir. ISBN: 9781921862953 (pbk.) 9781921862960 (eBook) Series: Aboriginal history monograph ; 25. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Gold mines and mining--Victoria--1851-1891. Aboriginal Australians--Victoria--History--19th century. Dewey Number: 994.503 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Published with the assistance of University of Ballarat (School of Business), Sovereign Hill Parks and Museum Association and Parks Victoria This publication has been supported by the Australian Historical Association Cover design with assistance from Evie Cahir Front Cover photo: ‘New diggings, Ballarat’ by Thomas Ham, 1851. Courtesy State Library of Victoria Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Preface and acknowledgements . .vii Introduction . 1 1 . Aboriginal people and mining . 5 2 . Discoverers and fossickers . 21 3 . Guiding . 35 4 . Trackers and Native Police . 47 Illustrations . 57 5 . Trade, commerce and the service sector . 67 6 . Co-habitation . 85 7. Off the goldfields . 103 8 . Social and environmental change . 109 9 . -

From Bavaria to Panama – Forest Pedagogic Concepts Around the Globe

FtForest PdPedagog ica lCtConcepts & MthdMethods around the Globe Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa Bavarian Forest National Park Praha Šumava National Park Bavarian Forest 69 000 ha National Park 24 250 ha Vienna Munich From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park Bavarian-Bohemian woodlands From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park Bavarian-Bohemian woodlands From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park Take a look at small things… From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park put the inconspicuous on the take time for things pedestral From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park experience nature with all your senses From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park theatre From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park Immediate and intensive care demands a lot of employees National Park rangers interns volunteers National Park forest guides voluntary ecological year From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park Guided tours From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park From Bavaria to Panama | Lukas Laux & Mónica Hinojosa | Bavarian Forest National Park Series of special guided tours „Glass Ark“ -

A Tongass Salmon Town

SITKA A Tongass Salmon Town A guide to sharing the story of this town, built on salmon and the forest that sustains them The species of Pacific salmon S 5 O K C I Chum(Dog, Keta) K N • Ecological generalists, they use streams large and small • Most widely distributed species of Pacific salmon E G • Develop prominent red and black tiger stripes along their sides when spawning Y • Eggs harvested as Ikura (caviar) for Japanese restaurants E Sockeye (Red) CHUM • Only spawn in river systems that flow from lakes • Filter-feeders, usually caught with nets, not hooks Here’s a trick that • Become scarlet red when spawning, head turns elementary school kids in dark green • Spend 18 months to two years in lake before going to sea Alaska use! 1. (Chinook) Thumb: King chum— Thumb rhymes with • Largest Pacific salmon, adapted to the largest rivers 2. Pointer finger:chum salmon • Can swim 1000+ miles upstream to spawning grounds • Accumulate fat for their journey causing their rich flavor the eye— • Live up to 5 years in the ocean sockeye Sockssalmon you in 3. Middle finger: biggest finger, your “king Silver(Coho) finger”— Your king salmon • Spend one year in fresh water and one year at sea 4. • Most sensitive to disturbances to habitat , consid- Ring finger: ered an “indicator species” for stream health you wear your silver Where • Prefer side channels of streams ring— silver salmon 5. Pinky finger: Your small- Pink (Humpy) est, pinky—pink salmon • The smallest Pacific salmon, often just 3-5 lbs. • Most abundant species in the Tongass, well-suited for smaller rivers • Separate populations spawn in odd and even years in each stream • At spawning, males develop a pronounced hump on back Salmon - Photos (cover): The winding headwaters of a salmon watershed—the veins and arteries of the Tongass, design transporting by Sitka Tlingit nutrients artist throughout Rhonda Reaney.