Richard Outram's Early Poems (1957–1988)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impact Re Port

Impact Report 2011-2012 Dear Supporters, Dear Friends, As a leading organization in arts educa- 2011/12 was a ground breaking year for tion, AFCY continues to grow through us. We reshaped ourselves to include community partnership. We are grateful a new Youth-led Program Division, for our family of networks who support and an enhanced Youth Mentorship our innovative programming for youth Program. Collectively, these directives, in under-resourced neighbourhoods. in collaboration with the families, com- We thrive on collaborative and creative munity partners and youth from the thinking and, working with our partners many communities we work with, offered and supporters, make high quality arts more than 8,000 children and youth high education accessible to all. quality community arts educational ex- periences. This enabled emerging youth It is an exciting time for AFCY; as our 20th artists to gain fresh skills and leadership anniversary approaches, we are working opportunities, paid training and peer-to- towards growing awareness of our work peer learning. All this translated to more among the greater community. On behalf chances for young people to innovate, of the Board of Directors, we thank you participate, navigate and connect to their for your support of AFCY, which truly community and to their city in new ways. makes a difference in the lives of young people. Together, we provide youth with Thank you for your continuous support. opportunities to find their own voices and to use their creativity to give back to Please follow us on Twitter to hear more their communities. about us: @ AFCYtoronto. Thank you for being part of our family, and helping to drive our success. -

Staff Report

STAFF REPORT May 11, 2006 To: Policy and Finance Committee and Economic Development and Parks Committee From: TEDCO/Toronto 2015 World Expo Corporation, Deputy City Managers and Chief Financial Officer Subject: Toronto 2015 World Expo Bid (All Wards) Purpose: The purpose of this report is to advise City Council on the results of the due dilligence undertaken by TEDCO and its subsidiary, Toronto World Expo Corporation; to recommend that City Council support a bid; to request the Government of Canada submit a bid to the Bureau International des Exposition (BIE) to host a World Expo in Toronto in 2015; and to direct the DCM/CFO, the City Solcitor and the Toronto World Expo Coporation to seek an agreement with other levels of government on a finanicial guarantee, capital funding framework, and a corporate governance structure. Financial Implications and Impact Statement: If Toronto’s bid is successful, the financial and economic consultant to the Toronto 2015 World Expo Corporation, Price Waterhouse Coopers, forecasts that hosting the World Expo will result in the proposed World Expo Corporation incurring an overall deficit of $700 million after $1.5 billion of legacy capital assets are included as shown in Table 1. The approach and methodology used by Price Waterhouse Coopers appears reasonable, although Finance staff have not had an opportunity to fully review their detailed, comprehensive study. - 2 - Table 1 - Capital and Operating Summary of the World Expo Corporation ($2006 Billions) World Expo Corporation Capital Summary: Capital Expenditures (2.8) Sale of Assets 0.1 Total Capital Costs (2.7) World Expo Corporation Operating Summary: Operating Expenditures (1.0) Financing Costs (0.6) Operating Revenues 1.3 Funding from Other Expo Revenues 0.8 Total Operating Profit 0.5 World Expo Corporation Estimated Net Expo Deficit (including Legacy (2.2) Expenditures) Residual Legacy Capital Assets 1.5 Overall Deficit (0.7) Price Waterhouse Coopers Waterhouse’s forecast includes total estimated capital expenditures of $2.8 billion. -

Patrick Warner Curriculum Vitae

PATRICK WARNER Memorial University of Newfoundland Queen Elizabeth II Library Telephone: (709) 864-6736 email: [email protected] Education 1996-1997 University of Western Ontario, London Ontario Masters of Library and Information Science 1989-1990 Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, Newfoundland Undergraduate studies in Archaeology 1985 Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, Newfoundland Bachelor of Arts Conjoint Major: Cultural Anthropology/ English Language and Literature Professional Positions Held at Memorial University January 2009 to present Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland: Special Collections Librarian • Responsible for the provision of access to the rare books collection and other special collections at Memorial University Libraries • Responsible for the promotion of collections to the university community, through web- site development, the creation of book exhibits, and participating in university classes as requested. • Collection development • Liaison with faculty as well as with past donors and potential future donors • Identifying and pursuing external funding opportunities. • Member of various Queen Elizabeth II Library committees and working groups. (see p.3) January 2005 to December 2008. Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland: Head of Document Delivery Services August 2000 to Jan. 2005 Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland: Head of Lending Services March to August 2000 St. John’s Public Libraries: Lending and Electronic Services Librarian 1999 to 2000 College of the North Atlantic; Topsail Road Campus. St. John’s, NF: Librarian 1998 to 1999 The C-CORE Information Centre. Memorial University Newfoundland: Librarian 1997 to 1998 The New York Public Library, New Dorp Regional Library and Huguenot Park Library. -

Workshop Flyer

Between: Embodiment in Science Teaching Workshop and Discussion June 20 th Inigo Rooms, East Wing Somerset House, KCL, Strand Campus A free, discipline specific workshop sponsored by the Higher Education Academy and the School of Biomedical Sciences, KCL. The target audience is professional educators but we encourage a broad delegate base. The workshop will explore the definitions and role of embodiment in science teaching and science practice. It complements the exhibition “Between” at the Inigo rooms, King’s College London, which features works by artists Susan Aldworth, Karen Ingham and Andrew Carnie. The workshop will draw speakers from a range of disciplines with the aim of developing a broad discussion on how we talk about and teach science. How are aspects of expertise and knowledge conferred within the gestures, movements, depictions and objects of scientific practice? How can understanding these elements of embodiment inform science learning and teaching? The discipline focus will be anatomy, the brain and biomedical sciences reflecting the themes of the Between exhibition, which will be open during the workshop. An early evening discussion with the Between artists on the nature of embodiment in art and science will be chaired by Martha Fleming and will be open to both workshop delegates and the general public. Numbers at this workshop will be limited to 30. Half of these places will initially be held for delegates outside KCL and allocated on a first-come, first-served basis. Research student travel will be subsidised by the -

Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled By: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C

OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C. Wallace Compiled in: June to August 2010 Last Updated: 17-Aug-10 Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 In Celebration of pp. 1-10 Official opening, OCC headquarters, This article is a series of photographs and the Ontario Crafts Crossroads, Joan Chalmers, Thoma Ewen, blurbs detailing the official opening of the Council Tamara Jaworska, Dora de Pedery, Judith OCC, the Crossroads exhibition, and some Almond-Best, Stan Wellington, David behind the scenes with the Council. Reid, Karl Schantz, Sandra Dunn. Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 Hi Fibres '76 p. 12 Exhibition, sculptural works, textile forms, This article details Hi Fibres '76, an OCC Gallery, Deirdre Spencer, Handcraft exhibition of sculptural works and textile House, Lynda Gammon, Madeleine forms in the gallery of the Ontario Crafts Chisholm, Charlotte Trende, Setsuko Council throughout February. Piroche, Bob Polinsky, Evelyn Roth, Charlotte Schneider, Phyllis gerhardt, Dianne Jillings, Joyce Cosgrove, Sue Proom, Margery Powel, Miriam McCarrell, Robert Held. Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 Communications pp. 1-6 First conference, structures and This article discusses the initial Weekend programs, Alan Gregson, delegates. conference of the OCC, in which the structure of the organization, the programs, and the affiliates benefits were discussed. Page 1 of 153 OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 The Affiliates of pp. -

A Night at the Garden (S): a History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship

A Night at the Garden(s): A History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship in the 1920s and 1930s by Russell David Field A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Russell David Field 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

VIEW LIVE MUSIC INDEX EMAIL [email protected] DEADLINE: Monday at 4Pm ABSINTHE 38 KING WILLIAM 905.529.0349 COPPER KETTLE 312 DUNDAS ST

GREATER HAMILTON’S INDEPENDENT VOICE FEBRUARY 14 — 20, 2019 VOL. 25 NO. 7 COMPLETE ENTERTAINMENTENTERTAINMENT FREEFREELISTINGS EVERY THURSDAY Over Time THE LEGO MOVIE 2 • PETE & KAY • DIGGING INTO DEVELOPMENT CHARGES • FREE WILL ASTROLOGY • REAL ESTATE 2 FEBRUARY 14 — 20, 2019 VIEW VIEW FEBRUARY 14 — 20, 2019 3 THEATRE 06 FROST BITES photo by: INSIDEGeorge Qua-Enoo THIS ISSUE FEBRUARY 14 — 20, 2019 06 COVER FROST BITES Cover Photo: George Qua-Enoo FORUM MUSIC 05 CATCH Growth Costs 08 Hamilton Music Notes 05 PERSPECTIVE Racism in Politics 12 Live Music Listing SCENE MOVIES 06 THEATRE The Day They Shot 16 REVIEW The Lego Movie 2 John Lennon 17 Movie Showtimes 06 THEATRE Frost Bites 07 THEATRE Drury Lane Music Hall ETC. 18 General Classifieds FOOD 19 Free Will Astrology 10 Dining Guide 19 Adult Classifieds 11 REVIEW Pete & Kay 370 MAIN STREET WEST, HAMILTON, ONTARIO L8P 1K2 HAMILTON 905.527.3343 FAX 905.527.3721 VIEW FOR ADVERTISING INQUIRIES: 905.527.3343 X102 EDITOR IN CHIEF Ron Kilpatrick x109 [email protected] OPERATIONS DIRECTOR CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING ACCOUNTING PUBLISHER Marcus Rosen x101 Liz Kay x100 Roxanne Green x103 Sean Rosen x102 [email protected] 1.866.527.3343 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ADVERTISING DEPT DISTRIBUTION CONTRIBUTORS LISTINGS EDITOR RandA distribution Rob Breszny • Gregory SENIOR CORPORATE Alison Kilpatrick x100 Owner:Alissa Ann latour Cruikshank • Sara Cymbalisty • REPRESENTATIVE [email protected] Manager:Luc Hetu Albert DeSantis • Darrin Ian Wallace x107 905-531-5564 DeRoches • Daniel Gariépy • amara [email protected] HAMILTON MUSIC NOTES [email protected] Allison M. Jones • T Kamermans • Michael Ric Taylor Klimowicz • Don McLean ADVERTISING [email protected] PRINTING • Brian Morton • Ric Taylor • REPRESENTATIVE Ricter Web Printing Michael Terry Al Corbeil x105 PRODUCTION [email protected] [email protected] PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT NO. -

Drawer Inventory Combined G

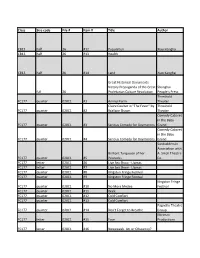

Class Size code File # Item # Title Author CB13 half 26 #12 Population Xiao Hangha CB13 half 26 #13 Health CB13 half 26 #14 Land Xiao Kanghai Great Historical Documents - Victory Propaganda of the Great Shanghai full 26 Proletarian Culture Revolution People's Press Threshold FC177 quarter 020C1 #1 Animal Farm Theater Claire Coulter in "The Fever" by Threshold FC177 quarter 020C1 #2 Wallace Shawn Theater Comedy Cabaret in the Baby FC177 quarter 020C1 #3 Serious Comedy for Oxymorons Grand Comedy Cabaret in the Baby FC177 quarter 020C1 #4 Serious Comedy for Oxymorons Grand Sunbuilders in Association with Brilliant Turquoise of her A. Small Theatre FC177 quarter 020C1 #5 Peacocks Co. FC177 letter 020C1 #6 Live Sex Show - Llamas FC177 letter 020C1 #7 Live Sex Show - Llamas FC177 quarter 020C1 #8 Kingston Fringe Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #9 Kingston Fringe Festival Kingston Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #10 No More Medea Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #11 Walk FC177 quarter 020C1 #12 Cold Comfort FC177 quarter 020C1 #13 Cold Comfort Pagnello Theatre FC177 quarter 020C1 #14 Don't Forget to Breathe Group Mirimax FC177 letter 020C1 #15 Face Productions FC177 letter 020C1 #16 Newsweek. Art or Obscenity? Month of Sundays, Broadway Bound, A Night at the Grand, Baby Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #17 Sex and Politics Theatre Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #18 Shaking Like a Leaf FC177 quarter 020C1 #19 Bent FC177 quarter 020C1 #20 Bent FC177 quarter 020C1 #21 Kennedy's Children FC177 quarter 020C1 #22 Dumbwaiter/Suppress FC177 letter 020C1 #23 Bath Haydon Theatre Kingston Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #24 Using Festival West of Eden FC177 quarter 020C1 #25 Big Girls Don't Cry Production Two One Act Plays: "Winners" A. -

1*1 Library and Archives

Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57480-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57480-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lntemet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne sur la Privacy Act some supporting forms protection de la vie privee, quelques may have been removed from this formulaires secondaires ont ete enleves de thesis. -

SKETCH-Fall-2005.Pdf

FALL 2005 A Publication for the Alumni, Students, Faculty SKETCH and Staff of Ontario College of Art & Design OCAD: LOOKING OUTWARD, REACHING UPWARDS PRESIDENT SARA DIAMOND AT WHODUNNIT? 2005. SKETCH PHOTO BY GEORGE WHITESIDE Ontario College of Art & Design is Canada’s Produced by the OCAD Communications Department largest university for art and design. Its mission is Designed by Hambly & Woolley Inc. to challenge each student to find a unique voice Contributors for this issue Cindy Ball, within a vibrant and creative environment, prepare Janis Cole, Sarah Eyton, Leanna McKenna, graduates to excel as cultural contributors in Laura Matthews, Sarah Mulholland Canada and beyond, and champion the vital role of art and design in society. Copy editing Maggie Keith Date of issue November 2005 Sketch magazine is published twice a year by the Ontario College of Art & Design for alumni, friends, The views expressed by contributors faculty, staff and students. are not necessarily those of the Ontario College of Art & Design. President Sara Diamond Charitable Registration #10779-7250 RR0001 Vice-President, Administration Peter Caldwell Canada Post Publications Vice-President, Academic Sarah McKinnon Agreement # 40019392 Dean, Faculty of Art Blake Fitzpatrick Printed on recycled paper Dean, Faculty of Design Lenore Richards Dean, Faculty of Liberal Studies Kathryn Shailer Return undeliverable copies to: Chair, Board of Governors Tony Caldwell Ontario College of Art & Design Chair, OCAD Foundation Robert Rueter 100 McCaul Street President, Alumni Association -

Biographies 9-10 May 2019

Collections in Circulation Mobile Museum Project conference Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew Biographies 9-10 May 2019 Claudia Augustat is the curator for South Felix Driver is Professor of Human Geography American Collections at the Weltmuseum Wien, at Royal Holloway, University of London, and a Austria, a position she has held since 2004. She Visiting Researcher at Kew. He has undertaken was awarded her PhD in Ethnology from the research on collections, scientific exploration and Goethe University in Frankfurt. Her research empire, often in collaboration with museums and focuses on the Amazon, material culture and heritage institutions. His books include Geography cultural memory, on collaborative curatorship and Militant (2001) and Hidden Histories of Exploration the decolonization of museum praxis. (2009, with Lowri Jones). Paul Basu is Professor of Anthropology at Martha Fleming is a Senior Researcher at the British SOAS, University of London. In recent years Museum, working on the early modern collections his regional specialization has focused on West of Hans Sloane. She has extensive experience with Africa – Sierra Leone (where he has worked on interdisciplinary and inter-institutional research landscape, memory and cultural heritage) and projects between museums and the academy, Nigeria, retracing the itineraries of the colonial notably at the Natural History Museum BMNH, the anthropologist N. W. Thomas. He is currently Victoria and Albert Museum, the Medical Museion leading a AHRC-funded project concerned with (Copenhagen) and the -

Ms. ORMSBY (ERIC) PAPERS Coll. 1980-Ongoing 424 13 Boxes (2.25 Metres)

Ms. ORMSBY (ERIC) PAPERS Coll. 1980-ongoing 424 13 boxes (2.25 metres) 2004 Accession Includes proofs, photographs (New York City, 1967), holograph notebooks, printed appearances in numerous journals such as The New Criterion; Books in Canada; videotaped appearance at Bentley College, September 20, 2002; David Solway manuscripts; correspondence with other writers, editors, publishers: John Black; Richard Outram; David Solway; Karen Mulhallen/Descant; Shlomo Dov Goitein; PhD thesis, Princeton; drafts and proofs of Al-Ghazali; galleys, correspondence and cover art for Daybreak at the Straits and Other Poems; Extent: 13 boxes (2.25 metres) Gift of Eric Ormsby 1 Ms. ORMSBY (ERIC) PAPERS Coll. 1980-ongoing 424 13 boxes (2.25 metres) Box 1 “Handlist of Arabic Manuscripts in the 34 folders Princeton University Library”, 1986, By Eric Ormsby and Rudolf Mach “Photos for Writing, taken by E. Ormsby in New York City (Fall 1967)” holograph notebooks holograph notes ‘Extraction’ and ‘Dicie Fletcher’ drafts for poem Folder 1 Holograph notebook, 1985-1986 Folder 2 Holograph notebook, 1988-1993 Folder 3 Poems and notes Holograph Word processed with holograph revisions Folders 4-10 “Photos for writing, taken by E. Ormsby in New York City (Fall 1967)” 33 black and white photographs 2 colour photographs, including one of Ormsby Folders 11-18 “Extraction”, also titled “Dicie Fletcher” various drafts, word processed with holograph revisions, some holograph Folder 19 “Filitosa” draft poem, word processed with holograph revisions Folder 20 David Solway manuscripts (word processed), including From the Herb Garden of Bartholomew the Englishman and The Properties of Things Folders 21-34 “Handlist of Arabic Manuscripts in the Princeton University Library”, 1986, 2 Ms.