1*1 Library and Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patrick Warner Curriculum Vitae

PATRICK WARNER Memorial University of Newfoundland Queen Elizabeth II Library Telephone: (709) 864-6736 email: [email protected] Education 1996-1997 University of Western Ontario, London Ontario Masters of Library and Information Science 1989-1990 Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, Newfoundland Undergraduate studies in Archaeology 1985 Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, Newfoundland Bachelor of Arts Conjoint Major: Cultural Anthropology/ English Language and Literature Professional Positions Held at Memorial University January 2009 to present Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland: Special Collections Librarian • Responsible for the provision of access to the rare books collection and other special collections at Memorial University Libraries • Responsible for the promotion of collections to the university community, through web- site development, the creation of book exhibits, and participating in university classes as requested. • Collection development • Liaison with faculty as well as with past donors and potential future donors • Identifying and pursuing external funding opportunities. • Member of various Queen Elizabeth II Library committees and working groups. (see p.3) January 2005 to December 2008. Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland: Head of Document Delivery Services August 2000 to Jan. 2005 Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland: Head of Lending Services March to August 2000 St. John’s Public Libraries: Lending and Electronic Services Librarian 1999 to 2000 College of the North Atlantic; Topsail Road Campus. St. John’s, NF: Librarian 1998 to 1999 The C-CORE Information Centre. Memorial University Newfoundland: Librarian 1997 to 1998 The New York Public Library, New Dorp Regional Library and Huguenot Park Library. -

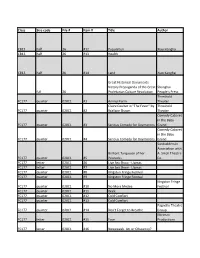

Drawer Inventory Combined G

Class Size code File # Item # Title Author CB13 half 26 #12 Population Xiao Hangha CB13 half 26 #13 Health CB13 half 26 #14 Land Xiao Kanghai Great Historical Documents - Victory Propaganda of the Great Shanghai full 26 Proletarian Culture Revolution People's Press Threshold FC177 quarter 020C1 #1 Animal Farm Theater Claire Coulter in "The Fever" by Threshold FC177 quarter 020C1 #2 Wallace Shawn Theater Comedy Cabaret in the Baby FC177 quarter 020C1 #3 Serious Comedy for Oxymorons Grand Comedy Cabaret in the Baby FC177 quarter 020C1 #4 Serious Comedy for Oxymorons Grand Sunbuilders in Association with Brilliant Turquoise of her A. Small Theatre FC177 quarter 020C1 #5 Peacocks Co. FC177 letter 020C1 #6 Live Sex Show - Llamas FC177 letter 020C1 #7 Live Sex Show - Llamas FC177 quarter 020C1 #8 Kingston Fringe Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #9 Kingston Fringe Festival Kingston Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #10 No More Medea Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #11 Walk FC177 quarter 020C1 #12 Cold Comfort FC177 quarter 020C1 #13 Cold Comfort Pagnello Theatre FC177 quarter 020C1 #14 Don't Forget to Breathe Group Mirimax FC177 letter 020C1 #15 Face Productions FC177 letter 020C1 #16 Newsweek. Art or Obscenity? Month of Sundays, Broadway Bound, A Night at the Grand, Baby Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #17 Sex and Politics Theatre Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #18 Shaking Like a Leaf FC177 quarter 020C1 #19 Bent FC177 quarter 020C1 #20 Bent FC177 quarter 020C1 #21 Kennedy's Children FC177 quarter 020C1 #22 Dumbwaiter/Suppress FC177 letter 020C1 #23 Bath Haydon Theatre Kingston Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #24 Using Festival West of Eden FC177 quarter 020C1 #25 Big Girls Don't Cry Production Two One Act Plays: "Winners" A. -

SKETCH-Fall-2005.Pdf

FALL 2005 A Publication for the Alumni, Students, Faculty SKETCH and Staff of Ontario College of Art & Design OCAD: LOOKING OUTWARD, REACHING UPWARDS PRESIDENT SARA DIAMOND AT WHODUNNIT? 2005. SKETCH PHOTO BY GEORGE WHITESIDE Ontario College of Art & Design is Canada’s Produced by the OCAD Communications Department largest university for art and design. Its mission is Designed by Hambly & Woolley Inc. to challenge each student to find a unique voice Contributors for this issue Cindy Ball, within a vibrant and creative environment, prepare Janis Cole, Sarah Eyton, Leanna McKenna, graduates to excel as cultural contributors in Laura Matthews, Sarah Mulholland Canada and beyond, and champion the vital role of art and design in society. Copy editing Maggie Keith Date of issue November 2005 Sketch magazine is published twice a year by the Ontario College of Art & Design for alumni, friends, The views expressed by contributors faculty, staff and students. are not necessarily those of the Ontario College of Art & Design. President Sara Diamond Charitable Registration #10779-7250 RR0001 Vice-President, Administration Peter Caldwell Canada Post Publications Vice-President, Academic Sarah McKinnon Agreement # 40019392 Dean, Faculty of Art Blake Fitzpatrick Printed on recycled paper Dean, Faculty of Design Lenore Richards Dean, Faculty of Liberal Studies Kathryn Shailer Return undeliverable copies to: Chair, Board of Governors Tony Caldwell Ontario College of Art & Design Chair, OCAD Foundation Robert Rueter 100 McCaul Street President, Alumni Association -

Ms. ORMSBY (ERIC) PAPERS Coll. 1980-Ongoing 424 13 Boxes (2.25 Metres)

Ms. ORMSBY (ERIC) PAPERS Coll. 1980-ongoing 424 13 boxes (2.25 metres) 2004 Accession Includes proofs, photographs (New York City, 1967), holograph notebooks, printed appearances in numerous journals such as The New Criterion; Books in Canada; videotaped appearance at Bentley College, September 20, 2002; David Solway manuscripts; correspondence with other writers, editors, publishers: John Black; Richard Outram; David Solway; Karen Mulhallen/Descant; Shlomo Dov Goitein; PhD thesis, Princeton; drafts and proofs of Al-Ghazali; galleys, correspondence and cover art for Daybreak at the Straits and Other Poems; Extent: 13 boxes (2.25 metres) Gift of Eric Ormsby 1 Ms. ORMSBY (ERIC) PAPERS Coll. 1980-ongoing 424 13 boxes (2.25 metres) Box 1 “Handlist of Arabic Manuscripts in the 34 folders Princeton University Library”, 1986, By Eric Ormsby and Rudolf Mach “Photos for Writing, taken by E. Ormsby in New York City (Fall 1967)” holograph notebooks holograph notes ‘Extraction’ and ‘Dicie Fletcher’ drafts for poem Folder 1 Holograph notebook, 1985-1986 Folder 2 Holograph notebook, 1988-1993 Folder 3 Poems and notes Holograph Word processed with holograph revisions Folders 4-10 “Photos for writing, taken by E. Ormsby in New York City (Fall 1967)” 33 black and white photographs 2 colour photographs, including one of Ormsby Folders 11-18 “Extraction”, also titled “Dicie Fletcher” various drafts, word processed with holograph revisions, some holograph Folder 19 “Filitosa” draft poem, word processed with holograph revisions Folder 20 David Solway manuscripts (word processed), including From the Herb Garden of Bartholomew the Englishman and The Properties of Things Folders 21-34 “Handlist of Arabic Manuscripts in the Princeton University Library”, 1986, 2 Ms. -

The Writescape Companion

The Writescape Companion Summer 2011 Sunday, Aug. 7 Summer writing Tasting the Page It looks like this summer is going to be a So what’s hot and what’s not? If you Taking description beyond hot one. I’m not complaining—I’ve been write for children, author Erin Thomas the five senses cold for far too long—but it got me can what’s cooking with a few Canadian ~~~ thinking about hot writing. publishers. She and Gwynn are teaming Saturday, Aug. 20 up to facilitate a six-week Writing for Woods, Water & Words Raw, first-draft writing is hot writing, Children course. A day of writing activities at writing straight from the creative brain, Glentula on Lake Seymour. writing more concerned with story than Then, there is the hot writing that comes ~~~ semantics. This summer let go with your when you are ‚in the zone,‛ when your Sunday, Aug. 28 writing: no internal editor; no telling characters are real people doing real Putting Flesh on the yourself it’s no good. Just write! Start with things and words are just pouring onto Bones the hot prompts in this issue, or check out the page. Ah, bliss! The secret is, this Building strong characters Inspiration Station to keep you going all kind of writing only comes when you ~~~ summer long. write often, preferably every day. Find a Mondays, Sept. 12 – Oct. 24 quiet spot in your garden, pack the kids Writing for Children Hot writing can also conjure up steamy off to grandma or escape to write for a The ins and outs of children’s sex scenes. -

The Porcupine's Quill Spring 2016

The Porcupine’s Quill DISTRIBUTED BY UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Spring 2016 Press sharply. Now Available as e-Books All of our frontlist, and select backlist, is now available inexpensively in pdf format for tablets. Contact us directly at: http: //store.porcupinesquill.ca or order through Google Play who will facilitate international sales in any number of local currencies. e-Book sales can also be accommodated through the book membership service Scribd. Todate the collection features six titles by P.K.Page: Brazilian Journal, Coal and Roses,Hand Luggage, Kaleidoscope, Mexican Journal and The Essential P.K.Page;seven titles by wood engraver George A. Walker: AIsfor Alice, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Book of Hours, The Life and Times of Conrad Black, The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson, The Wordless LeonardCohen Songbook; Trudeau: La Vie en Rose and all thirteen titles in our series of ‘Essential Poets’ featuring work by Margaret Avison, Earle Birney,Don Coles, Robert Gibbs, Daryl Hine, George Johnston, Travis Lane, Kenneth Leslie, TomMarshall, Richard Outram, James Reaney and Anne Wilkinson, as well as P.K.Page. Other recent releases include Thoughts on Driving to Venus by Christopher Pratt and The Grand River by Marianne Brandis and Gerard Brender a`Brandis. Libraries may prefer to order from EbscoHost or in Canada from desLibris (Gibson Library Services). 2 The Porcupine’s Quill /Spring 2016 Catalogue Fabulous Fictions &PECULIAR PRACTICES Leon Rooke&TonyCalzetta APRIL ° Afantastical literary experiment in which text and image collide to form an irreverent satire of society’s indifference to the artist. In Fabulous Fictions & Peculiar Practices,politics and economics sprawl comfortably alongside prurient dissertations on sex, marriage and aging as Leon Rooke and Tony Calzetta masterfully unfold a narrative of society’s utter indifference to the sorry plight of the artist. -

Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections

CLARA THOMAS ARCHIVES Inventory of the Nancy Barbara Fleming fonds Inventory #F0537 The digitization of this finding aid was made possible - in part or entirely - through the Canadian Culture Online Program of Canadian Heritage, the National Archives of Canada and the Canadian Council of Archives. page 2 F0537 - Nancy Barbara Fleming fonds Fonds/Collection Number: F0537 Title: Nancy Barbara Fleming fonds Dates: ca. 1953-2006 Extent: 0.08 m of textual records 15 prints : b&w and col. ; 86 x 51 cm and smaller Biographical Sketch/ Nancy Barbara Fleming was born in 1931 to Barbara Ellen and Gordon Administrative History: McCullough Chisholm, and spent her childhood in West Toronto Junction. She studied commercial arts at Western Technical High School, and married Allan Robb Fleming in 1951. They lived in London, England from 1953 to 1955 and visited Europe while Allan studied graphic design and worked in advertising, and Nancy worked as an office manager for a nylon stocking manufacturer. They met Canadian poet Richard Outram and his eventual wife, artist Barbara Howard, while in London, and they remained lifelong friends. Upon their return to Canada, Allan set up a freelance business and became creative director of the typesetting firm, Cooper & Beatty. Nancy became a mother and for the next 20 years brought up her three children while being an executive wife as Allan moved through senior posts at MacLaren Advertising and the University of Toronto Press. Nancy administrated Allan's busy freelance consultancy, and handled the financial management of graphic design and corporate branding projects. When Allan and Nancy separated in 1976, Nancy found work as the Toronto office co-ordinator for John Roberts, Pierre Elliot Trudeau's Secretary of State. -

Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections (CTASC)

CLARA THOMAS ARCHIVES Inventory of the Allan Robb Fleming fonds Inventory #F0529 The digitization of this finding aid was made possible - in part or entirely - through the Canadian Culture Online Program of Canadian Heritage, the National Archives of Canada and the Canadian Council of Archives. page 2 F0529 - Allan Robb Fleming fonds Fonds/Collection Number: F0529 Title: Allan Robb Fleming fonds Dates: 1853-1995, predominant 1953-1978 Extent: 5.5 metres of textual records and other material Biographical Sketch/ Allan Robb Fleming was born in Toronto on 7 May 1929 to immigrant Scottish Administrative History: parents, Isabella Osborne Fleming and Allan Stevenson Fleming. His mother was a nurse and teacher; his father a switchman and later a clerk for Canadian National Railways. He studied commercial art at the Western Technical School until 1945, and was hired as an illustrator immediately on graduation into the mail order catalogue illustration department of T. Eaton Company. During this time he met Nancy Barbara Chisholm, whom he was married in 1951. After leaving Eaton's in 1947, Fleming worked as a layout artist with the Art Associates Studio and later as the art director of the advertising firm Aiken McCracken. He joined another advertising firm, Art and Design Service, in 1951, and worked with clients such as Ford, Helena Rubinstein, and Kaiser-Frazer until April 1953. Fleming started his own freelance practice at this time, beginning a relationship with Steve Barootes that included the design of print material and signage for Barootes' restaurant, The Fifth Avenue. He also attended a series of Typography Workshops at Cooper & Beatty Typesetters run by Carl Dair. -

Nancy Barbara Fleming Fonds (F0537)

York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) Finding Aid - Nancy Barbara Fleming fonds (F0537) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: July 31, 2018 Language of description: English York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) 305 Scott Library, 4700 Keele Street, York University Toronto Ontario Canada M3J 1P3 Telephone: 416-736-5442 Fax: 416-650-8039 Email: [email protected] http://www.library.yorku.ca/ccm/ArchivesSpecialCollections/index.htm https://atom.library.yorku.ca//index.php/nancy-barbara-fleming-fonds Nancy Barbara Fleming fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Collection holdings .......................................................................................................................................... 5 F0537-2008-033/001(01), -

Endorsers of the Open Letter to Presidents Biden and Putin

Endorsers of the Open Letter to Presidents Biden and Putin Political, military and religious leaders, legislators, academics/scientists and other representatives of civil society POLITICAL LEADERS: Jaakko Iloniemi, Finland. Ambassador Edy Korthals Altes, The Netherlands. Former Ambassador to the United States. Former Ambassador of The Netherlands to Spain and Member, European Leadership Network; President of the World Conference of Religions for Peace; Ambassador Enkhsaikhan Jargalsaikhan, Mongolia. Lord (Des) Browne of Ladyton, United Kingdom. President, Blue Banner. Former Ambassador to the U.N.; Member of UK House of Lords. Former Defence Secretary. Chair, European Leadership Network; Hon Jan Kavan, Czech Republic. Former Minister of Foreign Affairs. Ingvar Carlsson, Sweden. Member, European Leadership Network Former Prime Minister of Sweden. Senior Member, European Leadership Network; Lord Kerr of Kinlochard, United Kingdom. Former UK Ambassador to the United States and the EU; Hans Corell, Sweden. Former Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs and the Osman Faruk Loğoğlu. Turkey. Legal Counsel of the United Nations (1994-2004); Former Ambassador to the United States. Former Undersecretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Member, Ambassador Sergio Duarte, Brazil. European Leadership Network; Former UN Under-Secretary-General for Disarmament Affairs. President of Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Budimir Loncar, Croatia. Affairs: Former Foreign Minister of Ex Yugoslavia. Member, European Leadership Network; Rolf Ekéus, Sweden. Senior Fellow SIPRI. Former Director of the United Nations Ambassador Peggy Mason, Canada. Special Commission on Iraq; President of the Rideau Institute, former Canadian Disarmament Ambassador; Hon Maria Fernanda Espinosa, Ecuador. rd President of the 73 UN General Assembly. Janusz Onyszkiewicz, Poland. Former Foreign Minister and Defence Minister; Former Defence Minister of Poland and Chair of the Executive Council of the Euro-Atlantic Association; Hon Gareth Evans, Australia. -

Witnessing the Remembering of Creation a Series of Events at the University of Toronto Takes GRANT HURLEY to the Genesis—And Future—Of Fine Printing in Canada

Witnessing the Remembering of Creation A series of events at the University of Toronto takes GRANT HURLEY to the genesis—and future—of fine printing in Canada. Plentiful amounts of discarded type and press equipment. An abundance of talented writers. And autodidact printers with verve and vision committed to putting that type to use and those writers to paper. All of these things came together to create a vibrant fine press printing community in Toronto during the 1970s and 1980s. A feeling of the close-knit community born in that era was present in a lecture, a series of exhibitions, and a new imprint launched on January 22, 2019 at the John M. Kelly Library of St. Michael’s College at the Signage for the exhibit at John M. Kelly Library. University of Toronto. The lecture featured (All photos by Grant Hurley) Robert MacDonald—designer, printer, publisher, typographer and co-founder of Dreadnaught Press—and was titled “All Crazy for Type, Goluska’s works are a special focus in two of Ink, Paper and Glue.” The exhibitions, spread the exhibits, thanks to the curatorial efforts of across five sites, are collectively titledCanadian Chester Gryski, a director of the Alcuin Society Fine Press and feature examples of beautiful and alumnus of St. Michael’s (Goluska was also fine press works from the collections of four of an alumnus). And the Kelly library has revived its the university’s federated college libraries and print studio with the hiring of Deborah Barnett, the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. Glenn who co-founded Dreadnaught with MacDonald, Glenn Goluska pictured at Robert MacDonald’s lecture. -

Gaspereau Press ¶ Printers & Publishers

Gaspereau Press ¶ Printers & Publishers a catalogue of five new books for spring 2013 dear reader do not abscond from your fate for you hold in your hands the ultimate spate of speculations on five books forthcoming in spring mmxiii from the inky & tenacious bibliophiles at Gaspereau Press printers and publishers toiling under the sign of the mirthful g 47 church avenue · kentville · nova scotia · canada literary outfitters & cultural wilderness guides since 1997 new poetry “I believe a book can be a labyrinth whose centre is the journey to itself,” writes Peter Sanger. “ A concerto grosso, not a singular declamation” And indeed in reading Sanger, individual books, like individual poems, may Fireship: profitably be read as layers in the strata of his oeuvre, each influenced by what was written before and influencing in turn what was to be writ- Early Poems ten next. Taken together, his books describe the long arc of his particu- lar sensitivity to language and his ever-evolving sense of nature, culture and place. “All the poems in Fireship,” writes Sanger, “concern where we 1965–1991 were, where we are, where we will be.” As well as his many prose projects, Gaspereau Press has been publish- PETER SANGER ing Sanger’s poetry since 2002, issuing two full-length collections – Ai- ken Drum and John Stokes’ Horse. While these volumes remain in print, Sanger’s first two collections, published elsewhere, have essentially dis- $25.95 | 9781554471218 | april appeared from view – The America Reel (1983) and Earth Moth (1991). With the blessing of their original publishers, Gaspereau Press is mark- Printed offset on laid paper making 192 pages trimmed ing Peter Sanger’s seventieth birthday in 2013 by reissuing his first two to 5 × 8 inches; Smyth sewn, bound in a paper cover and poetry books in a single volume, collecting with them 24 previously un- enfolded in an offset-printed jacket.