The Humanities and Its Publics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ivo Banac SILENCING the ARCHIVAL VOICE: THE

I. Banac, Silencing the archival voice: the destruction of archives and other obstacles to archival research in post-communist Eastern Europe, Arh. vjesn., god. 42 (1999), str. 217-222 Ivo Banac Yale University Department of History P.P.Box 208324 New Haven SAD SILENCING THE ARCHIVAL VOICE: THE DESTRUCTION OF ARCHIVES AND OTHER OBSTACLES TO ARCHIVAL RESEARCH IN POST-COMMUNIST EASTERN EUROPE UDK 930.253:355.4](4)"199" Izlaganje sa znanstvenog skupa Sve zbirke arhivskoga gradiva imaju svoje zaštitnike - vlastite glasove, koji prenose suhoparne statistike, birokratsku opreznost, ali isto tako ljutnju i strast po vijesnih sudionika te težnje za plemenitim i manje plemenitim ciljevima. Povjesniča ri i drugi istraživači imaju popise nedoličnih i smiješnih priča o "dostupnosti" i ne dostatku iste. Do sloma sustava 1989/1990. to je bila obvezatna značajka komuni stičkih režima u istočnoj Evropi. Danas, naročito kao posljedica ratova usmjerenih na brisanje pamćenja, arhivski glasovi su utišani daleko težim zaprekama - najgo rom od svih, ogromnim uništavanjem arhivskoga gradiva. U nekim slučajevima, kao u Bosni i Hercegovini, uništenje arhivskoga gradiva bilo je dio ratne strategije. Uni štite povijest "drugoga " i na putu ste da vašeg proglašenog "neprijatelja " lišite verti kalnog kontinuiteta. Ova strategija je kako pogrešna, tako i štetna. Uništenje napulj- skog Arhiva u vrijeme Drugoga svjetskog rata, uništilo je povijest Napulja isto tako malo, kao što razaranje Orijentalnog instituta u Sarajevu može ukinuti povijest Bo sne i Hercegovine. Ali to je unatoč tomu velika nesreća. A kako povijest nije sasvim nezavisna, to nisu nikada niti izvori. Razaranje jedne arhivske zbirke šteti svima - ne samo određenoj grupi ili grupaciji. -

History 600: Public Intellectuals in the US Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Office

Hannah Arendt W.E.B. DuBois Noam Chomsky History 600: Public Intellectuals in the U.S. Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Lecturer: Ronit Stahl Class Meetings: Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 M 11 a.m.-1 p.m. email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Room: Mosse Hum. 5257 Prof. RR’s Office Hours: R.S.’s Office Hours: T 3- M 9 a.m.-11a.m. 5 p.m. This course is designed for students interested in exploring the life of the mind in the twentieth-century United States. Specifically, we will examine the life of particular minds— intellectuals of different political, moral, and social persuasions and sensibilities, who have played prominent roles in American public life over the course of the last century. Despite the common conception of American culture as profoundly anti-intellectual, we will evaluate how professional thinkers and writers have indeed been forces in American society. Our aim is to investigate the contested meaning, role, and place of the intellectual in a democratic, capitalist culture. We will also examine the cultural conditions, academic and governmental institutions, and the media for the dissemination of ideas, which have both fostered and inhibited intellectual production and exchange. Roughly the first third of the semester will be devoted to reading studies in U.S. and comparative intellectual history, the sociology of knowledge, and critical social theory. In addition, students will explore the varieties of public intellectual life by becoming familiarized with a wide array of prominent American philosophers, political and social theorists, scientists, novelists, artists, and activists. -

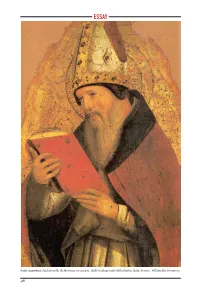

Saint Augustine, by Antonello De Messina, Circa 1472. Galleria Regionale Della Sicilia, Italy

ESSAY Caption?? Saint Augustine, by Antonello de Messina, circa 1472. Galleria Regionale della Sicilia, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commons. 48 READING AUGUSTINE James Turner JoHnson ugustine’s influence runs deep and broad through Western Christian Adoctrine and ethics. This paper focuses on two particular examples of this influence: his thinking on political order and on just war. Augustine’s conception of political order and the Christian’s proper relation to it, developed most fully in his last and arguably most comprehensive theological work, The City of God, is central in both Catholic and mainline Protestant thinking on the political community and the proper exercise of government. Especially important in recent debate, the origins of the Christian idea of just war trace to Augustine. Exactly how Augustine has been read and understood on these topics, as well as others, has varied considerably depending on context, so the question in each and every context is how to read and understand Augustine. Paul Ramsey was right to insist, them as connected. When they fundamental problem for any in the process of developing are separated, one or another reading of Augustine on these his own understanding of just kind of distortion is the result. subjects. war, that in Christian thinking the idea of just war does not It is, of course, possible to ap- My discussion begins by exam- stand alone but is part of a com- proach either or both of these ining the use of Augustine by prehensive conception of good topics without taking account two prominent recent thinkers politics. This also describes of Augustine’s thinking or its on just war, Paul Ramsey and Augustine’s thinking. -

An Interview with Jean Bethke Elshtain

Just War, Humanitarian Intervention and Equal Regard: An Interview with Jean Bethke Elshtain Jean Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics at the University of Chicago. Among her books are Just War Against Terror. The Burden of American Power in a Violent World (Basic Books, 2003), Jane Addams and the Dream of American Democracy (Basic Books, 2001), Women and War (Basic Books, 1987) and Democracy on Trial (Basic Books, 1995), which Michael Walzer called ‘the work of a truly independent, deeply serious, politically engaged, and wonderfully provocative political theorist.’ The interview was conducted on 1 September 2005. Alan Johnson: Unusually for a political philosopher you have been willing to discuss the personal and familial background to your work. You have sought a voice ‘through which to traverse …particular loves and loyalties and public duties.’ Can you say something about your upbringing, as my mother would have called it, and your influences, and how these have helped to form the characteristic concerns of your political philosophy? Jean Bethke Elshtain: Well, my mother would have called it the same thing, so our mothers’ probably shared a good deal. There is always a confluence of forces at work in the ideas that animate us but upbringing is critical. In my own case this involved a very hard working, down to earth, religious, Lutheran family background. I grew up in a little village of about 180 people where everybody pretty much knew everybody else. You learn to appreciate the good and bad aspects of that. There is a tremendous sense of security but you realise that sometimes people are too nosy and poke into your business. -

Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism in This Paper We Will Look

Andrew Jason Cohen, “Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism,” Pre-Publication Version Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism In this paper we will look at three versions of the charge that liberalism’s emphasis on individuals is detrimental to community—that it encourages a pernicious disregard of others by fostering a particular understanding of the individual and the relation she has with her society. According to that understanding, individuals are fundamentally independent entities who only enter into relations by choice and society is nothing more than a venture voluntarily entered into in order to better ourselves. Communitarian critics argue that since liberals neglect the degree to which individuals are dependent upon their society for their self-understanding and understanding of the good, they encourage individuals to maintain a personal distance from others in their society. The detrimental effect this distancing is said to have on communities is often called “asocial individualism” or “asocialism.” Jean Bethke Elshtain sums up this view: “Within a world of choice-making Robinson Crusoes, disconnected from essential ties with one another, any constraint on individual freedom is seen as a burden, most often an unacceptable one.”1 In the first three sections, we look at the first version of the charge that liberalism is detrimental to community. This concerns the “distancing” discussed above: the claim is that liberalism encourages individuals to opt out of relationships too readily. In the fourth section, we briefly discuss the second variant: that liberalism induces aggressive behavior. Finally, in sections five and six, we address the third version of the charge: liberalism does not provide for the social trust that is necessary for cooperation and the provision of communal goods. -

The Formation of Croatian National Identity

bellamy [22.5].jkt 21/8/03 4:43 pm Page 1 Europeinchange E K T C The formation of Croatian national identity ✭ This volume assesses the formation of Croatian national identity in the 1990s. It develops a novel framework that calls both primordialist and modernist approaches to nationalism and national identity into question before applying that framework to Croatia. In doing so it not only provides a new way of thinking about how national identity is formed and why it is so important but also closely examines 1990s Croatia in a unique way. An explanation of how Croatian national identity was formed in an abstract way by a historical narrative that traces centuries of yearning for a national state is given. The book goes on to show how the government, opposition parties, dissident intellectuals and diaspora change change groups offered alternative accounts of this narrative in order to The formation legitimise contemporary political programmes based on different visions of national identity. It then looks at how these debates were in manifested in social activities as diverse as football and religion, in of Croatian economics and language. ✭ This volume marks an important contribution to both the way we national identity bellamy study nationalism and national identity and our understanding of post-Yugoslav politics and society. A centuries-old dream ✭ ✭ Alex J. Bellamy is lecturer in Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Queensland alex j. bellamy Europe Europe THE FORMATION OF CROATIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY MUP_Bellamy_00_Prelims 1 9/3/03, 9:16 EUROPE IN CHANGE : T C E K already published Committee governance in the European Union ⁽⁾ Theory and reform in the European Union, 2nd edition . -

In Memoriam Ivo Banac

In memoriam Ivo Banac Martin Previšić Ivo Banac (1947-2020) ana 30. lipnja 2020. godine u Svetoj Nedjelji umro je povjesničar Ivo Banac, professor emeritus Sveučilišta Yale i umirovljeni profesor Sve- Dučilišta u Zagrebu. Odlaskom profesora Ive Banca nastala je velika praznina u hrvatskoj i svjetskoj historiografiji. Mali je broj povjesničara s ovih prostora koji su izgradili takvu impresivnu akademsku i društvenu karijeru u Hrvatskoj i svijetu kao što je ona profesora Banca. Međutim, od početka života njegov samostalan i neobičan put obilježila su dinamična događanja druge polovine 20. stoljeća. Obiteljska povijest, a na koncu i njegovo zanimanje činili su život i karijeru Ive Banca vrlo posebni- ma, što se očituje u njegovu djelu. Sigurno su velike mijene utjecale i na samog Banca, njegove perspektive i uvjerenja, životni put i pristup dolazećim izazovima. Dubrovnik je činio velik dio njegova emocionalnog backgrounda pa je taj grad cijeloga života bio predmet Bančeva interesa i mjesto koje je jedino, u punom smislu te riječi, zvao domom. Kao potomak ugledne dubrovačke obitelji Banac je odmalena nosio u sebi osjećaj pripadnosti specifičnoj kulturi koja je u sebi sažimala obilježja lokalnoga građanskog sloja, brojne kozmopolitske trendove, ali i usječenost u tradicijske osnove tog vremena. Bančev je život, kao i brojne sudbine vezane uz njega, posebno odredilo iskustvo Drugoga svjetskog rata. Pobjedom komunista i uspostavom novog sustava nakon 1945, promijenjena je sudbina njegove obitelji jer su imućni i građanski slojevi i industrijalci bili posebno pogođeni revolucionarnim nastojanjima Partije, definiranima u stalji- nizacijskim efektima nacionalizacije. U tim okolnostima rođen je Ivo Banac 1. ožujka 1947. u Dubrovniku. Njegovo je djetinjstvo proteklo u ozračju ne samo općenito teškog vremena već i novog položaja njegove obitelji. -

Kiss: Keep It Simple, Stupid!

UDK 327(497.5:73)”1990/1992”323.15(73=163.4 2)”1990/1992” KISS: Keep IT Simple, Stupid! Critical Observations OF the Croatian American Intellectuals During the Establishment OF Political Relations Between Croatia and the United States, 1990-1992 Albert Bing* Croatia secured its state independence during the turbulent collapse of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Socijalistička Federativna Republika Jugoslavija - SFRJ) from 1990 to 1992 under exceptionally complex interna- tional circumstances. The world’s most influential countries, first and fore- most the United States, upheld the unity and territorial integrity of Yugoslavia despite clear indications of its violent break-up.1 After the democratic chang- es of 1990, an exceptionally important matter for Croatia’s independence was the internationalization of the Yugoslav crisis. The unraveling of the Yugoslav state union dictated a redefinition of the status of the republics as its constitu- ent units; in this process, in line with national homogenization which consti- tuted the dominant component of societal transition at the time, the question of redefining national identities came to the forefront. The problem of pre- senting Croatia as a self-contained geopolitical unit, entailing arguments that should accompany its quest for state independence, imposed itself in this con- text. Political proclamations in the country, media presentation and lobbying associated with the problem of becoming acquainted with the political cul- tures and establishments of influential countries -

Guide to the Jean Bethke Elshtain Papers 1935-2017

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Jean Bethke Elshtain Papers 1935-2017 © 2017 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Restrictions on Use 3 Citation 4 Biographical Note 4 Scope Note 6 Related Resources 9 Subject Headings 10 INVENTORY 10 Series I: Personal 10 Subseries 1: General Personal Ephemera 10 Subseries 2: Education 14 Subseries 3: Curriculum Vitae, Calendars, and Itineraries 19 Series II: Correspondence 22 Series III: Subject Files 48 Series IV: Writings by Others 67 Series V: Writings 84 Subseries 1: Articles and Essays 84 Subseries 2: Speaking Engagements 158 Subseries 3: Books 242 Series VI: Teaching 256 Series VII: Professional Organizations 279 Series VIII: Honors and Awards 291 Series IX: Audiovisual 292 Series X: Oversize 298 Series XI: Restricted 299 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.ELSHTAINJB Title Elshtain, Jean Bethke. Papers Date 1935-2017 Size 124 linear feet (237 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract Jean Bethke Elshtain (1941-2013) was a political theorist, ethicist, author, and public intellectual. She was the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics with joint appointments at the Divinity School, the Department of Political Science, and the Committee on International Relations at the University of Chicago. The collection includes personal ephemera; correspondence; subject files; materials related to her writings and speaking engagements; university administrative and teaching materials; records documenting Elshtain's activities in professional, nonprofit, and governmental organizations; awards; photographs; audio and video recordings; and posters. -

Review Article Just a War Against Terror? Jean Bethke Elshtain's

Review article Just a war against terror? Jean Bethke Elshtain’s burden and American power NICHOLAS RENGGER* Just war against terror: ethics and the burden of American power in a violent world. By Jean Bethke Elshtain. New York: Basic Books. 2003. 208pp. £13.55. 046501 9102. This book is something of a puzzle. Over the past two decades Jean Elshtain has fashioned a body of work that glitters like few others in contemporary American political theory. Broad in range, fiercely articulate and unique in tone, she has contributed to a bewilderingly wide spectrum of topics: the public/private dichotomy;1 the character and role of the history of political thought;2 the importance of the family in social and political thought;3 the character, obliga- tions and requirements of democratic politics; the intertwining of the ethical and the political in international politics;4 and, most recently, the centrality of religion in people’s lives and in political life.5 One prominent theme that has recurred in her writing and teaching over the years has been a concern for the various manifestations of what she often terms ‘civic virtue’, and especially for the particular manifestation of it that occurs in connection with war. Indeed, along with perhaps Michael Walzer and James Turner Johnson,6 Elshtain has become one of the best-known contemporary advocates of the just war tradition. In her prize-winning Women and war, in her edited volume on just war theory and in her book on Augustine, as well as in many essays in many different places, Elshtain has sought to ram home the message that the world in *I am grateful to Chris Brown, Ian Hall, Caroline Kennedy-Pipe, Oliver Richmond and Caroline Soper for their comments on this article. -

Why Augustine? Why Now?

Catholic University Law Review Volume 52 Issue 2 Winter 2003 Article 3 2003 Why Augustine? Why Now? Jean Bethke Elshtain Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Jean B. Elshtain, Why Augustine? Why Now?, 52 Cath. U. L. Rev. 283 (2003). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol52/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES WHY AUGUSTINE? WHY NOW? Jean Bethke Elshtain' The fate of Saint Augustine in the world of academic political theory has been, at best, mixed. First, he was enveloped in that blanket of suspicion cast over all "religious" or "theological" thinkers: do such thinkers really belong with the likes of Plato and Aristotle, Machiavelli and Hobbes, or Marx and Mill? Were their eyes not cast heavenward rather than fixed resolutely on human political and social affairs? In addition, there are particular features of Saint Augustine's writing that make the importance of his works difficult to decipher. He was an ambitiously discursive and narrative thinker. From the time of his conversion to Catholic Christianity in 386 to his death as Bishop of Hippo in 430, Augustine wrote some 117 books.' During his life, Augustine wrote on the central themes of Christian life and theology: the nature of God and the human person; the problem of evil; free will and determinism; war and human aggression; the bases of social life and political order; church doctrine; and Christian vocations, to name a few.2 Although several of his works follow an argumentative line in a manner most often favored by political theorists, especially given the distinctly juridical or legalistic cast of so much modern political theory, Augustine most often paints bold strokes on an expansive canvas. -

CURRICULUM VITAE KATHERINE VERDERY September 2009

CURRICULUM VITAE KATHERINE VERDERY September 2009 ADDRESSES Office: Ph.D. Program in Anthropology, Graduate Center, City University of New York 365 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10016-4309 Office phone- 212-817-8015, Fax - 212-817-1501 E-mail [email protected] Home: 730 Fort Washington Ave, 5B, New York, NY 10040. Phone 212-543-1789. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 2005- Julien J. Studley Faculty Scholar and Distinguished Professor, Anthropology Program, City University of New York Graduate Center. 2003-04 Acting Chair, Department of Anthropology, University of Michigan 2000-2002 Director, Center for Russian and East European Studies, University of Michigan 1997-2005 Eric R. Wolf Professor of Anthropology, University of Michigan 1989-92 Chair, Department of Anthropology, Johns Hopkins University 1987-97 Professor of Anthropology, Johns Hopkins University 1983-87 Associate Professor of Anthropology, Johns Hopkins University 1977-83 Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Johns Hopkins University EDUCATION 1977 Ph.D., Anthropology, Stanford University, Stanford, California 1971 M.A., Anthropology, Stanford University, Stanford, California 1970 B.A., Anthropology, Reed College, Portland, Oregon CURRENT SPECIALIZATIONS Eastern Europe, Romania; socialism and postsocialist transformation; property; political anthropology; Secret Police organization. HONORS, SPECIAL LECTURES, AND AWARDS 2008 First Daphne Berdahl Memorial Lecture, University of Minnesota 2007 George A. Miller Endowment Visiting Professor, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign 2004-2005