IT IS the RESPONSIBILITY of Intellectuals to Speak the Truth and to Expose Lies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literary, Subsidiary, and Foreign Rights Agents

Literary, Subsidiary, and Foreign Rights Agents A Mini-Guide by John Kremer Copyright © 2011 by John Kremer All rights reserved. Open Horizons P. O. Box 2887 Taos NM 87571 575-751-3398 Fax: 575-751-3100 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.bookmarket.com Introduction Below are the names and contact information for more than 1,450+ literary agents who sell rights for books. For additional lists, see the end of this report. The agents highlighted with a bigger indent are known to work with self-publishers or publishers in helping them to sell subsidiary, film, foreign, and reprint rights for books. All 325+ foreign literary agents (highlighted in bold green) listed here are known to work with one or more independent publishers or authors in selling foreign rights. Some of the major literary agencies are highlighted in bold red. To locate the 260 agents that deal with first-time novelists, look for the agents highlighted with bigger type. You can also locate them by searching for: “first novel” by using the search function in your web browser or word processing program. Unknown author Jennifer Weiner was turned down by 23 agents before finding one who thought a novel about a plus-size heroine would sell. Her book, Good in Bed, became a bestseller. The lesson? Don't take 23 agents word for it. Find the 24th that believes in you and your book. When querying agents, be selective. Don't send to everyone. Send to those that really look like they might be interested in what you have to offer. -

History 600: Public Intellectuals in the US Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Office

Hannah Arendt W.E.B. DuBois Noam Chomsky History 600: Public Intellectuals in the U.S. Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Lecturer: Ronit Stahl Class Meetings: Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 M 11 a.m.-1 p.m. email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Room: Mosse Hum. 5257 Prof. RR’s Office Hours: R.S.’s Office Hours: T 3- M 9 a.m.-11a.m. 5 p.m. This course is designed for students interested in exploring the life of the mind in the twentieth-century United States. Specifically, we will examine the life of particular minds— intellectuals of different political, moral, and social persuasions and sensibilities, who have played prominent roles in American public life over the course of the last century. Despite the common conception of American culture as profoundly anti-intellectual, we will evaluate how professional thinkers and writers have indeed been forces in American society. Our aim is to investigate the contested meaning, role, and place of the intellectual in a democratic, capitalist culture. We will also examine the cultural conditions, academic and governmental institutions, and the media for the dissemination of ideas, which have both fostered and inhibited intellectual production and exchange. Roughly the first third of the semester will be devoted to reading studies in U.S. and comparative intellectual history, the sociology of knowledge, and critical social theory. In addition, students will explore the varieties of public intellectual life by becoming familiarized with a wide array of prominent American philosophers, political and social theorists, scientists, novelists, artists, and activists. -

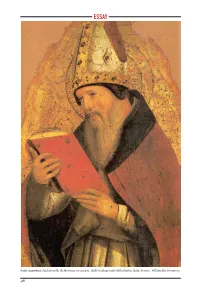

Saint Augustine, by Antonello De Messina, Circa 1472. Galleria Regionale Della Sicilia, Italy

ESSAY Caption?? Saint Augustine, by Antonello de Messina, circa 1472. Galleria Regionale della Sicilia, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commons. 48 READING AUGUSTINE James Turner JoHnson ugustine’s influence runs deep and broad through Western Christian Adoctrine and ethics. This paper focuses on two particular examples of this influence: his thinking on political order and on just war. Augustine’s conception of political order and the Christian’s proper relation to it, developed most fully in his last and arguably most comprehensive theological work, The City of God, is central in both Catholic and mainline Protestant thinking on the political community and the proper exercise of government. Especially important in recent debate, the origins of the Christian idea of just war trace to Augustine. Exactly how Augustine has been read and understood on these topics, as well as others, has varied considerably depending on context, so the question in each and every context is how to read and understand Augustine. Paul Ramsey was right to insist, them as connected. When they fundamental problem for any in the process of developing are separated, one or another reading of Augustine on these his own understanding of just kind of distortion is the result. subjects. war, that in Christian thinking the idea of just war does not It is, of course, possible to ap- My discussion begins by exam- stand alone but is part of a com- proach either or both of these ining the use of Augustine by prehensive conception of good topics without taking account two prominent recent thinkers politics. This also describes of Augustine’s thinking or its on just war, Paul Ramsey and Augustine’s thinking. -

The Boisi Center Report the Boisi Center for Religion and American Public Life at Boston College

The Boisi Center Report the boisi center for religion and american public life at boston college vol. 10 v no. 2 v june 2010 From the Director When we began our work at the Boisi Center ten years ago, we had high hopes that the Prophetic Voices Lecture would become our signature event each year. The idea was to invite a prominent person who has demonstrated usual moral courage, and who has thought publically about his or her faith in ways that inspire action in the world. Many distinguished individuals have joined us for this purpose, including Sr. Helen Prejean, Fuller Seminary’s Richard Mouw, and Muslim scholar Abdullahi An-Na’im. This year, though, may have been the best we have hosted. Committed to intellectual diversity, I wanted a conservative thinker for the lecture and immediately thought of Professor Robert George, of Princeton University. No sooner did he accept our invitation than the New York Times Magazine ran a major profile of him. Professor George’s talk on natural law and human dignity was deeply nuanced and fascinating. Rarely have I seen so many pay attention for so long. I am enormously grateful to Robby George for joining us, and for saying such gracious things about us afterwards on the Mirror of Justice blog. This semester the Boisi Center also hosted a lecture by our benefactor and friend Geoff Boisi, who enthralled a large audience with his candid and extremely interesting talk on the Wall Street financial crisis. It was terrific to have this visit from Geoff, his wife Rene, and their son John, a student at BC. -

Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think and Why It Matters

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think nda Why It Matters Amanda Daily Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Daily, Amanda, "Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think nda Why It Matters" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2230. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2230 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Claremont McKenna College Why Hollywood Isn’t As Liberal As We Think And Why It Matters Submitted to Professor Jon Shields by Amanda Daily for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 and Spring 2019 April 29, 2019 2 3 Abstract Hollywood has long had a reputation as a liberal institution. Especially in 2019, it is viewed as a highly polarized sector of society sometimes hostile to those on the right side of the aisle. But just because the majority of those who work in Hollywood are liberal, that doesn’t necessarily mean our entertainment follows suit. I argue in my thesis that entertainment in Hollywood is far less partisan than people think it is and moreover, that our entertainment represents plenty of conservative themes and ideas. In doing so, I look at a combination of markets and artistic demands that restrain the politics of those in the entertainment industry and even create space for more conservative productions. Although normally art and markets are thought to be in tension with one another, in this case, they conspire to make our entertainment less one-sided politically. -

An Interview with Jean Bethke Elshtain

Just War, Humanitarian Intervention and Equal Regard: An Interview with Jean Bethke Elshtain Jean Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics at the University of Chicago. Among her books are Just War Against Terror. The Burden of American Power in a Violent World (Basic Books, 2003), Jane Addams and the Dream of American Democracy (Basic Books, 2001), Women and War (Basic Books, 1987) and Democracy on Trial (Basic Books, 1995), which Michael Walzer called ‘the work of a truly independent, deeply serious, politically engaged, and wonderfully provocative political theorist.’ The interview was conducted on 1 September 2005. Alan Johnson: Unusually for a political philosopher you have been willing to discuss the personal and familial background to your work. You have sought a voice ‘through which to traverse …particular loves and loyalties and public duties.’ Can you say something about your upbringing, as my mother would have called it, and your influences, and how these have helped to form the characteristic concerns of your political philosophy? Jean Bethke Elshtain: Well, my mother would have called it the same thing, so our mothers’ probably shared a good deal. There is always a confluence of forces at work in the ideas that animate us but upbringing is critical. In my own case this involved a very hard working, down to earth, religious, Lutheran family background. I grew up in a little village of about 180 people where everybody pretty much knew everybody else. You learn to appreciate the good and bad aspects of that. There is a tremendous sense of security but you realise that sometimes people are too nosy and poke into your business. -

MADE in HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED by BEIJING the U.S

MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence 1 MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION 1 REPORT METHODOLOGY 5 PART I: HOW (AND WHY) BEIJING IS 6 ABLE TO INFLUENCE HOLLYWOOD PART II: THE WAY THIS INFLUENCE PLAYS OUT 20 PART III: ENTERING THE CHINESE MARKET 33 PART IV: LOOKING TOWARD SOLUTIONS 43 RECOMMENDATIONS 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 53 ENDNOTES 54 Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ade in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing system is inconsistent with international norms of Mdescribes the ways in which the Chinese artistic freedom. government and its ruling Chinese Communist There are countless stories to be told about China, Party successfully influence Hollywood films, and those that are non-controversial from Beijing’s warns how this type of influence has increasingly perspective are no less valid. But there are also become normalized in Hollywood, and explains stories to be told about the ongoing crimes against the implications of this influence on freedom of humanity in Xinjiang, the ongoing struggle of Tibetans expression and on the types of stories that global to maintain their language and culture in the face of audiences are exposed to on the big screen. both societal changes and government policy, the Hollywood is one of the world’s most significant prodemocracy movement in Hong Kong, and honest, storytelling centers, a cinematic powerhouse whose everyday stories about how government policies movies are watched by millions across the globe. -

Jonathan Y. Rowe Phd Thesis

MICHAL, CONTRADICTING VALUES UNDERSTANDING THE MORAL DILEMMA FACED BY SAUL'S DAUGHTER Jonathan Y. Rowe A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2009 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/639 This item is protected by original copyright Michal, Contradicting Values Understanding the Moral Dilemma Faced by Saul’s Daughter A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Divinity in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jonathan Y. Rowe September 2008 St Mary’s College The University of St Andrews ABSTRACT Value conflicts due to cultural differences are an increasingly pressing issue in many societies. Because Old Testament texts hail from a very different milieu to our own they may provide new perspectives upon contemporary conflicts and, in this context, the present dissertation investigates one particular value clash in 1 Samuel. Studies of Old Testament ethics have attended to narrative only relatively recently. Although social-scientific interpretation has a longer pedigree, there are important debates about how to employ the fruits of anthropology in biblical studies. The first part of this thesis, therefore, attends to methodological issues, advancing four main propositions. First, attention should be paid to the moral goods that feature in the text. Second, the family, a central feature of Old Testament morality, should be understood as a set of practices rather than an institution. Third, ‘models’ of social action that purport to comprehend the social world of the Bible should be used only cautiously. -

Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism in This Paper We Will Look

Andrew Jason Cohen, “Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism,” Pre-Publication Version Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism In this paper we will look at three versions of the charge that liberalism’s emphasis on individuals is detrimental to community—that it encourages a pernicious disregard of others by fostering a particular understanding of the individual and the relation she has with her society. According to that understanding, individuals are fundamentally independent entities who only enter into relations by choice and society is nothing more than a venture voluntarily entered into in order to better ourselves. Communitarian critics argue that since liberals neglect the degree to which individuals are dependent upon their society for their self-understanding and understanding of the good, they encourage individuals to maintain a personal distance from others in their society. The detrimental effect this distancing is said to have on communities is often called “asocial individualism” or “asocialism.” Jean Bethke Elshtain sums up this view: “Within a world of choice-making Robinson Crusoes, disconnected from essential ties with one another, any constraint on individual freedom is seen as a burden, most often an unacceptable one.”1 In the first three sections, we look at the first version of the charge that liberalism is detrimental to community. This concerns the “distancing” discussed above: the claim is that liberalism encourages individuals to opt out of relationships too readily. In the fourth section, we briefly discuss the second variant: that liberalism induces aggressive behavior. Finally, in sections five and six, we address the third version of the charge: liberalism does not provide for the social trust that is necessary for cooperation and the provision of communal goods. -

Institute Expands Internship Opportunities Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University Jeanne Shaheen, Director

DECEMBER 2005 30 Years of Forums Archived New Frontier Awards Presented New Mayors Briefed George Magazine in the Forum New Survey Released U.S. Senator Barack Obama meets with 2005 IOP summer interns on the U.S. Capitol steps. Institute Expands Internship Opportunities Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University Jeanne Shaheen, Director After joining the Institute of Politics in July, I want you all to know how very appreciative I am to have this opportunity to serve as IOP Director. I am pleased to announce that the Institute will be receiving new University endowment funds this year. The funds will be used to expand our internship program, to create an initiative for development of leadership skills among undergraduate women, and to offer a scholarship to a SAC alumnus to attend the John F. Kennedy School of Government. This fall, Harvard students and IOP staff continued their work to foster politi- cal engagement on campus and in our community—below are highlights of some of our exciting programs: • After nearly thirty years of fantastic speeches and panels held in the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum, in early January we will launch a search- able video archive of Forum programs dating from 1978 which will be available on the IOP website. • At the end of November, we welcomed nearly 20 big city mayors from across the country for our Newly-Elected Mayors Program. The conference, co-hosted by the U.S. Conference of Mayors, helps new mayors take on the practical challenges of urban governance. • Our National Campaign hosted its fall conference, “Beyond Voting: College Students and Political Engagement,” focused on non-voting political engagement. -

Guide to the Jean Bethke Elshtain Papers 1935-2017

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Jean Bethke Elshtain Papers 1935-2017 © 2017 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Restrictions on Use 3 Citation 4 Biographical Note 4 Scope Note 6 Related Resources 9 Subject Headings 10 INVENTORY 10 Series I: Personal 10 Subseries 1: General Personal Ephemera 10 Subseries 2: Education 14 Subseries 3: Curriculum Vitae, Calendars, and Itineraries 19 Series II: Correspondence 22 Series III: Subject Files 48 Series IV: Writings by Others 67 Series V: Writings 84 Subseries 1: Articles and Essays 84 Subseries 2: Speaking Engagements 158 Subseries 3: Books 242 Series VI: Teaching 256 Series VII: Professional Organizations 279 Series VIII: Honors and Awards 291 Series IX: Audiovisual 292 Series X: Oversize 298 Series XI: Restricted 299 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.ELSHTAINJB Title Elshtain, Jean Bethke. Papers Date 1935-2017 Size 124 linear feet (237 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract Jean Bethke Elshtain (1941-2013) was a political theorist, ethicist, author, and public intellectual. She was the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics with joint appointments at the Divinity School, the Department of Political Science, and the Committee on International Relations at the University of Chicago. The collection includes personal ephemera; correspondence; subject files; materials related to her writings and speaking engagements; university administrative and teaching materials; records documenting Elshtain's activities in professional, nonprofit, and governmental organizations; awards; photographs; audio and video recordings; and posters. -

Review Article Just a War Against Terror? Jean Bethke Elshtain's

Review article Just a war against terror? Jean Bethke Elshtain’s burden and American power NICHOLAS RENGGER* Just war against terror: ethics and the burden of American power in a violent world. By Jean Bethke Elshtain. New York: Basic Books. 2003. 208pp. £13.55. 046501 9102. This book is something of a puzzle. Over the past two decades Jean Elshtain has fashioned a body of work that glitters like few others in contemporary American political theory. Broad in range, fiercely articulate and unique in tone, she has contributed to a bewilderingly wide spectrum of topics: the public/private dichotomy;1 the character and role of the history of political thought;2 the importance of the family in social and political thought;3 the character, obliga- tions and requirements of democratic politics; the intertwining of the ethical and the political in international politics;4 and, most recently, the centrality of religion in people’s lives and in political life.5 One prominent theme that has recurred in her writing and teaching over the years has been a concern for the various manifestations of what she often terms ‘civic virtue’, and especially for the particular manifestation of it that occurs in connection with war. Indeed, along with perhaps Michael Walzer and James Turner Johnson,6 Elshtain has become one of the best-known contemporary advocates of the just war tradition. In her prize-winning Women and war, in her edited volume on just war theory and in her book on Augustine, as well as in many essays in many different places, Elshtain has sought to ram home the message that the world in *I am grateful to Chris Brown, Ian Hall, Caroline Kennedy-Pipe, Oliver Richmond and Caroline Soper for their comments on this article.