"Man of No Party": Tzvetan Tdorov and Intellectual Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History 600: Public Intellectuals in the US Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Office

Hannah Arendt W.E.B. DuBois Noam Chomsky History 600: Public Intellectuals in the U.S. Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Lecturer: Ronit Stahl Class Meetings: Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 M 11 a.m.-1 p.m. email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Room: Mosse Hum. 5257 Prof. RR’s Office Hours: R.S.’s Office Hours: T 3- M 9 a.m.-11a.m. 5 p.m. This course is designed for students interested in exploring the life of the mind in the twentieth-century United States. Specifically, we will examine the life of particular minds— intellectuals of different political, moral, and social persuasions and sensibilities, who have played prominent roles in American public life over the course of the last century. Despite the common conception of American culture as profoundly anti-intellectual, we will evaluate how professional thinkers and writers have indeed been forces in American society. Our aim is to investigate the contested meaning, role, and place of the intellectual in a democratic, capitalist culture. We will also examine the cultural conditions, academic and governmental institutions, and the media for the dissemination of ideas, which have both fostered and inhibited intellectual production and exchange. Roughly the first third of the semester will be devoted to reading studies in U.S. and comparative intellectual history, the sociology of knowledge, and critical social theory. In addition, students will explore the varieties of public intellectual life by becoming familiarized with a wide array of prominent American philosophers, political and social theorists, scientists, novelists, artists, and activists. -

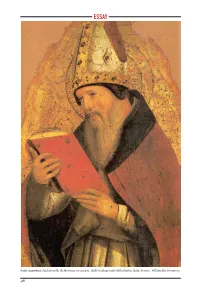

Saint Augustine, by Antonello De Messina, Circa 1472. Galleria Regionale Della Sicilia, Italy

ESSAY Caption?? Saint Augustine, by Antonello de Messina, circa 1472. Galleria Regionale della Sicilia, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commons. 48 READING AUGUSTINE James Turner JoHnson ugustine’s influence runs deep and broad through Western Christian Adoctrine and ethics. This paper focuses on two particular examples of this influence: his thinking on political order and on just war. Augustine’s conception of political order and the Christian’s proper relation to it, developed most fully in his last and arguably most comprehensive theological work, The City of God, is central in both Catholic and mainline Protestant thinking on the political community and the proper exercise of government. Especially important in recent debate, the origins of the Christian idea of just war trace to Augustine. Exactly how Augustine has been read and understood on these topics, as well as others, has varied considerably depending on context, so the question in each and every context is how to read and understand Augustine. Paul Ramsey was right to insist, them as connected. When they fundamental problem for any in the process of developing are separated, one or another reading of Augustine on these his own understanding of just kind of distortion is the result. subjects. war, that in Christian thinking the idea of just war does not It is, of course, possible to ap- My discussion begins by exam- stand alone but is part of a com- proach either or both of these ining the use of Augustine by prehensive conception of good topics without taking account two prominent recent thinkers politics. This also describes of Augustine’s thinking or its on just war, Paul Ramsey and Augustine’s thinking. -

An Interview with Jean Bethke Elshtain

Just War, Humanitarian Intervention and Equal Regard: An Interview with Jean Bethke Elshtain Jean Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics at the University of Chicago. Among her books are Just War Against Terror. The Burden of American Power in a Violent World (Basic Books, 2003), Jane Addams and the Dream of American Democracy (Basic Books, 2001), Women and War (Basic Books, 1987) and Democracy on Trial (Basic Books, 1995), which Michael Walzer called ‘the work of a truly independent, deeply serious, politically engaged, and wonderfully provocative political theorist.’ The interview was conducted on 1 September 2005. Alan Johnson: Unusually for a political philosopher you have been willing to discuss the personal and familial background to your work. You have sought a voice ‘through which to traverse …particular loves and loyalties and public duties.’ Can you say something about your upbringing, as my mother would have called it, and your influences, and how these have helped to form the characteristic concerns of your political philosophy? Jean Bethke Elshtain: Well, my mother would have called it the same thing, so our mothers’ probably shared a good deal. There is always a confluence of forces at work in the ideas that animate us but upbringing is critical. In my own case this involved a very hard working, down to earth, religious, Lutheran family background. I grew up in a little village of about 180 people where everybody pretty much knew everybody else. You learn to appreciate the good and bad aspects of that. There is a tremendous sense of security but you realise that sometimes people are too nosy and poke into your business. -

Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism in This Paper We Will Look

Andrew Jason Cohen, “Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism,” Pre-Publication Version Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism In this paper we will look at three versions of the charge that liberalism’s emphasis on individuals is detrimental to community—that it encourages a pernicious disregard of others by fostering a particular understanding of the individual and the relation she has with her society. According to that understanding, individuals are fundamentally independent entities who only enter into relations by choice and society is nothing more than a venture voluntarily entered into in order to better ourselves. Communitarian critics argue that since liberals neglect the degree to which individuals are dependent upon their society for their self-understanding and understanding of the good, they encourage individuals to maintain a personal distance from others in their society. The detrimental effect this distancing is said to have on communities is often called “asocial individualism” or “asocialism.” Jean Bethke Elshtain sums up this view: “Within a world of choice-making Robinson Crusoes, disconnected from essential ties with one another, any constraint on individual freedom is seen as a burden, most often an unacceptable one.”1 In the first three sections, we look at the first version of the charge that liberalism is detrimental to community. This concerns the “distancing” discussed above: the claim is that liberalism encourages individuals to opt out of relationships too readily. In the fourth section, we briefly discuss the second variant: that liberalism induces aggressive behavior. Finally, in sections five and six, we address the third version of the charge: liberalism does not provide for the social trust that is necessary for cooperation and the provision of communal goods. -

Guide to the Jean Bethke Elshtain Papers 1935-2017

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Jean Bethke Elshtain Papers 1935-2017 © 2017 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Restrictions on Use 3 Citation 4 Biographical Note 4 Scope Note 6 Related Resources 9 Subject Headings 10 INVENTORY 10 Series I: Personal 10 Subseries 1: General Personal Ephemera 10 Subseries 2: Education 14 Subseries 3: Curriculum Vitae, Calendars, and Itineraries 19 Series II: Correspondence 22 Series III: Subject Files 48 Series IV: Writings by Others 67 Series V: Writings 84 Subseries 1: Articles and Essays 84 Subseries 2: Speaking Engagements 158 Subseries 3: Books 242 Series VI: Teaching 256 Series VII: Professional Organizations 279 Series VIII: Honors and Awards 291 Series IX: Audiovisual 292 Series X: Oversize 298 Series XI: Restricted 299 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.ELSHTAINJB Title Elshtain, Jean Bethke. Papers Date 1935-2017 Size 124 linear feet (237 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract Jean Bethke Elshtain (1941-2013) was a political theorist, ethicist, author, and public intellectual. She was the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics with joint appointments at the Divinity School, the Department of Political Science, and the Committee on International Relations at the University of Chicago. The collection includes personal ephemera; correspondence; subject files; materials related to her writings and speaking engagements; university administrative and teaching materials; records documenting Elshtain's activities in professional, nonprofit, and governmental organizations; awards; photographs; audio and video recordings; and posters. -

Review Article Just a War Against Terror? Jean Bethke Elshtain's

Review article Just a war against terror? Jean Bethke Elshtain’s burden and American power NICHOLAS RENGGER* Just war against terror: ethics and the burden of American power in a violent world. By Jean Bethke Elshtain. New York: Basic Books. 2003. 208pp. £13.55. 046501 9102. This book is something of a puzzle. Over the past two decades Jean Elshtain has fashioned a body of work that glitters like few others in contemporary American political theory. Broad in range, fiercely articulate and unique in tone, she has contributed to a bewilderingly wide spectrum of topics: the public/private dichotomy;1 the character and role of the history of political thought;2 the importance of the family in social and political thought;3 the character, obliga- tions and requirements of democratic politics; the intertwining of the ethical and the political in international politics;4 and, most recently, the centrality of religion in people’s lives and in political life.5 One prominent theme that has recurred in her writing and teaching over the years has been a concern for the various manifestations of what she often terms ‘civic virtue’, and especially for the particular manifestation of it that occurs in connection with war. Indeed, along with perhaps Michael Walzer and James Turner Johnson,6 Elshtain has become one of the best-known contemporary advocates of the just war tradition. In her prize-winning Women and war, in her edited volume on just war theory and in her book on Augustine, as well as in many essays in many different places, Elshtain has sought to ram home the message that the world in *I am grateful to Chris Brown, Ian Hall, Caroline Kennedy-Pipe, Oliver Richmond and Caroline Soper for their comments on this article. -

Why Augustine? Why Now?

Catholic University Law Review Volume 52 Issue 2 Winter 2003 Article 3 2003 Why Augustine? Why Now? Jean Bethke Elshtain Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Jean B. Elshtain, Why Augustine? Why Now?, 52 Cath. U. L. Rev. 283 (2003). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol52/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES WHY AUGUSTINE? WHY NOW? Jean Bethke Elshtain' The fate of Saint Augustine in the world of academic political theory has been, at best, mixed. First, he was enveloped in that blanket of suspicion cast over all "religious" or "theological" thinkers: do such thinkers really belong with the likes of Plato and Aristotle, Machiavelli and Hobbes, or Marx and Mill? Were their eyes not cast heavenward rather than fixed resolutely on human political and social affairs? In addition, there are particular features of Saint Augustine's writing that make the importance of his works difficult to decipher. He was an ambitiously discursive and narrative thinker. From the time of his conversion to Catholic Christianity in 386 to his death as Bishop of Hippo in 430, Augustine wrote some 117 books.' During his life, Augustine wrote on the central themes of Christian life and theology: the nature of God and the human person; the problem of evil; free will and determinism; war and human aggression; the bases of social life and political order; church doctrine; and Christian vocations, to name a few.2 Although several of his works follow an argumentative line in a manner most often favored by political theorists, especially given the distinctly juridical or legalistic cast of so much modern political theory, Augustine most often paints bold strokes on an expansive canvas. -

Lincoln's Evocation of Natural Rights Still Reverberates in American Politics

Civil War Book Review Summer 2001 Article 5 Right Makes Might: Lincoln's Evocation Of Natural Rights Still Reverberates In American Politics Jean Bethke Elshtain Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Elshtain, Jean Bethke (2001) "Right Makes Might: Lincoln's Evocation Of Natural Rights Still Reverberates In American Politics," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 3 : Iss. 3 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol3/iss3/5 Elshtain: Right Makes Might: Lincoln's Evocation Of Natural Rights Still Re Review 'RIGHT MAKES MIGHT' Lincoln's evocation of natural rights still reverberates in American politics Elshtain, Jean Bethke Summer 2001 Jaffa, Harry V. A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War. Rowman and Littlefield, 2000-11-01. $35.00 ISBN 847699528 Harry V. Jaffa takes his time. The wait is well worth it. Forty-one years separate the publication of Jaffa's recognized classic, Crisis of the House Divided (University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226391132, $20.00 softcover), and this new work on Abraham Lincoln's political thought. A third volume is anticipated. A distinguished professor of political philosophy, Jaffa approaches texts through an interpretive method he owes to the philosopher Leo Strauss. Strauss, according to Jaffa, "taught that one must make every attempt to understand a writer as he understood himself." Pressing this theme when the subject is a powerful political thinker as well as America's greatest president requires engaging the full political implications, in historic context, of Lincoln's complex and eloquent arguments against slavery and for the American constitutional experiment. -

Augustine's Just War Ethics in Reinhold Niebuhr's Realism and Jean Bethke Elshtain's Selected Works

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 12, Ver. III (Dec. 2015) PP 74-82 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Augustine’s Just War Ethics In Reinhold Niebuhr’s Realism And Jean Bethke Elshtain’s Selected Works: A Response To The Boko Haram Insurgence In North East Nigeria Ajibola G. Ilesanmi Abstract: This paper identifies issues associated with wars and conflicts to be existential problems. They are commonly decried but yet have continue to pervade the theatre of interhuman relation. War and conflicts occur not only premised on distinctive political and economic differences but extends to issues of religious and even social differences – of course the last two categories often betray some forms of political and economic motifs. From this understanding that war situation has often been part of human experiences, this paper assumes that current issues that border on such problems are better considered from previous perspectives to avoid pitfalls, and to better navigate the often tensed path to resolution and peace. It is from this understanding that this paper considers the thoughts of Augustine1 through the lenses of Reinhold Niebuhr2 and Jean Bethke Elshtain3’s proposals on de iure Christian attitude to war. While both thinkers present an understanding that Christians should not imbibe pacifisms as a virtue in the face of injustice and violence, this paper argues that Niebuhr’s realism is inadequate to accommodate the reality of the moral issues associated with jus in bello principle of non-combatant immunity. The paper proposes Elshtain’s position which reflects the consciousness of a Christian realist as an approach to adopting Augustine’s thoughts on war. -

ACCEPTED for PUBLICATION Feminist Christian Realism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION Feminist Christian Realism: Vulnerability, Obligation, and Power Politicsi Caron E. Gentry University of St Andrews School of International Relations The Arts Building The Scores St Andrews KY16 9AX UNITED KINGDOM [email protected] Biography: Caron E. Gentry is a lecturer in the School of International Relations at the University of St Andrews. Caron's work has focused on gender and terrorism for over a decade. Having written on women’s involvement in politically violent groups with articles in various journals her publications also include (with Laura Sjoberg) Mothers, Monsters, Whores: Women’s Violence in Global Politics (Zed Books, 2007) and the edited volume, Women, Gender, and Terrorism (University of Georgia Press, 2011). She is also published in political theology with a focus on the Just War tradition and its relationship with marginalized persons in international affairs. Her most recent book is Offering Hospitality: Questioning Christian Approaches to War (University of Notre Dame Press, 2013). Abstract: While Christianity and feminism may seem at odds with one another, both make normative claims about justice and addressing the needs of those on the margins of power. This paper explores what feminism contributes to Christian realism. The current revival of Niebuhrian Christian realism highlights how much it still has to offer as a theoretical underpinning for policy and governance. However, Christian realism remains wedded to masculinist abstractions and power structures, such as the balance of power, that are ultimately harmful to those on the margins. -

Law and the Moral Life

Symposium Legal Scholarship in the Humanities: The t View from Inside the Quadrangle Law and the Moral Life Jean Bethke Elshtain* Let me begin with a story from the trenches. On a public radio call-in program in the thick of the Clinton impeachment imbroglio, I found myself being bombarded with denunciations from irate citizens. Most callers seemed to believe I was either a member of the "Christian Right" or part of a "vast right-wing conspiracy" because I claimed that there had been just a bit wanting in the President's behavior as President in the conduct of the Lewinsky scandal. Most importantly, from an ethical perspective, the President made ill use of so many people: His secretary, staff, Cabinet officers, trusted t Papers Delivered at a panel organized by Professor Andrew Kull, Emory University, at the 1999 AALS conference in New Orleans, Louisiana. * Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics at the University of Chicago. Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities, Vol. 11, Iss. 2 [1999], Art. 4 Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities [Vol. 11: 383 advisers, and even his wife were all called upon to lie on his behalf and in the interest of such a low matter. Clearly, something interesting had happened in the body politic when activities of this sort, occurring in the most public place in the country-the White House-and in the office "part" (not the residence "part"), are covered automatically by a claim to "privacy." "Our laws protect privacy," one riled-up citizen proclaimed, "and what you want to do would legislate morality. -

Jean Bethke Elshtain

JEAN BETHKE ELSHTAIN Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics University of Chicago Theology and Politics: A Match Made in Heaven or Hell? 2013 Charles E. Test, M.D. Distinguished Lectures TUESDAY APRIL Everybody Wants 23 to Be a Critic WEDNESDAY APRIL The Dark Knight 24 and the Saint THURSDAY APRIL Harry Potter and 25 Saint Augustine on Evil James Madison Program All Lectures begin at 4:30 p.m. in American Ideals and Institutions Princeton University 83 Prospect Avenue in Lewis Library 120 Princeton, NJ 08540 609-258-5107 http://princeton.edu/sites/jmadison Lectures, published 2008). In addition, Professor Elshtain has edited numerous books. She writes frequently for journals of civic opinion and lectures widely in the United States and abroad on themes of democracy, ethical dilemmas, religion and politics, and international relations. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; JEAN BETHKE ELSHTAIN is the Laura Spelman Rockefeller a Guggenheim Fellow; a Fellow at the Bellagio Center of the Professor of Social and Political Ethics, Divinity School, The Rockefeller Foundation; holder of the Maguire Chair in Ethics University of Chicago, with appointments in Political Science at the Library of Congress; and a Fellow at the Institute for and the Committee on International Relations. She is also Advanced Studies, Princeton, where she also served on the a Visiting Distinguished Professor of Religion and Politics at Board of Trustees. She has been a Phi Beta Kappa Lecturer Baylor University. She joined the faculty of the University of and in 2002 she received the Goodnow Award, the highest Massachusetts/Amherst where she taught from 1973 to 1988.