A.S.C.E.N.T.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

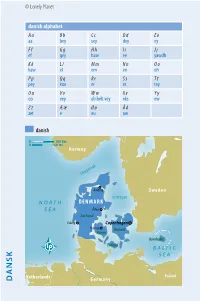

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

1.0 Firearms History

1.0 Firearms History 1.0.1 Introduction While a history of firearms should start with the earliest of hand cannons, progressing through the It may seem that a history of firearms is an illogical wheel lock, miquelet and so on. For this book, way to begin this book, but any competent forensic however, it will start at the flintlock, as it is unlikely firearms examiner needs to have a good working that anything earlier would be encountered in every- knowledge of this subject matter. As such, it should day case work. A much more comprehensive history form part of the court qualification process at the of firearms is offered in Appendix 4. beginning of any trial. Having said that, though, it would be unreasonable to expect a firearms examiner with many years’ experience to be able to give, for 1.0.2 The flintlock (Figure 1.0.1) example, a precise date for the introduction of the Anson and Deeley push button fore-end. Such an The flintlock ignition system really signalled the esoteric piece of firearms history may have formed advent of an easy-to-use firearm with a simple part of the examiner’s training many years ago, but mechanism for the discharge of a missile via a unless s/he had a particular interest in shotgun powdered propellant. In this type of weapon, the history it would be unlikely that s/he would remem- propellant was ignited via a spark produced by ber little other than an approximate date or period. striking a piece of flint against a steel plate. -

Status of the Baltic/Wadden Sea Population of the Common Eider Somateria M

Baltic/Wadden Sea Common Eider 167 Status of the Baltic/Wadden Sea population of the Common Eider Somateria m. mollissima M. Desholm1, T.K. Christensen1, G. Scheiffarth2, M. Hario3, Å. Andersson4, B. Ens5, C.J. Camphuysen6, L. Nilsson7, C.M. Waltho8, S-H. Lorentsen9, A. Kuresoo10, R.K.H. Kats5,11, D.M. Fleet12 & A.D. Fox1 1Department of Coastal Zone Ecology, National Environmental Research Institute, Grenåvej 12, 8410 Rønde, Denmark. Email: [email protected]/[email protected]/[email protected] 2Institut für Vogelforschung, ‘Vogelwarte Helgoland’, An der Vogelwarte 21, D - 26386 Wilhelmshaven, Germany. Email: [email protected] 3Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, Söderskär Game Research Station. P.O.Box 6, FIN-00721 Helsinki, Finland. Email: [email protected] 4Ringgatan 39 C, S-752 17 Uppsala, Sweden. Email: [email protected] 5Alterra, P.O. Box 167, 1790 AD Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands. Email:[email protected]/[email protected] 6Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (Royal NIOZ), P.O. Box 59, 1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands. Email: [email protected] 7Department of Animal Ecology, University of Lund, Ecology Building, S-223 62 Lund, Sweden. Email: [email protected] 873 Stewart Street, Carluke, Lanarkshire, Scotland, UK, ML8 5BY. Email: [email protected] 9Norwegian Institute for Nature Research. Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway Email: [email protected] 10Institute of Zoology and Botany, Riia St. 181, 51014, Tartu, Estonia. Email: [email protected] 11Department of Animal Ecology, University of Groningen, Kerklaan 30, 9751 NH, Groningen, The Netherlands. -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

Evidence from Hamburg's Import Trade, Eightee

Economic History Working Papers No: 266/2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Economic History Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, London, UK. T: +44 (0) 20 7955 7084. F: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY WORKING PAPERS NO. 266 – AUGUST 2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Email: [email protected] Abstract The study combines information on some 180,000 import declarations for 36 years in 1733–1798 with published prices for forty-odd commodities to produce aggregate and commodity specific estimates of import quantities in Hamburg’s overseas trade. In order to explain the trajectory of imports of specific commodities estimates of simple import demand functions are carried out. Since Hamburg constituted the principal German sea port already at that time, information on its imports can be used to derive tentative statements on the aggregate evolution of Germany’s foreign trade. The main results are as follows: Import quantities grew at an average rate of at least 0.7 per cent between 1736 and 1794, which is a bit faster than the increase of population and GDP, implying an increase in openness. Relative import prices did not fall, which suggests that innovations in transport technology and improvement of business practices played no role in overseas trade growth. -

Wars Between the Danes and Germans, for the Possession Of

DD 491 •S68 K7 Copy 1 WARS BETWKEX THE DANES AND GERMANS. »OR TllR POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. BV t>K()F. ADOLPHUS L. KOEPPEN FROM THE "AMERICAN REVIEW" FOR NOVEMBER, U48. — ; WAKS BETWEEN THE DANES AND GERMANS, ^^^^ ' Ay o FOR THE POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. > XV / PART FIRST. li>t^^/ On feint d'ignorer que le Slesvig est une ancienne partie integTante de la Monarchie Danoise dont I'union indissoluble avec la couronne de Danemarc est consacree par les garanties solennelles des grandes Puissances de I'Eui'ope, et ou la langue et la nationalite Danoises existent depuis les temps les et entier, J)lus recules. On voudrait se cacher a soi-meme au monde qu'une grande partie de la popu- ation du Slesvig reste attacliee, avec une fidelite incbranlable, aux liens fondamentaux unissant le pays avec le Danemarc, et que cette population a constamment proteste de la maniere la plus ener- gique centre une incorporation dans la confederation Germanique, incorporation qu'on pretend medier moyennant une armee de ciuquante mille hommes ! Semi-official article. The political question with regard to the ic nation blind to the evidences of history, relations of the duchies of Schleswig and faith, and justice. Holstein to the kingdom of Denmark,which The Dano-Germanic contest is still at the present time has excited so great a going on : Denmark cannot yield ; she has movement in the North, and called the already lost so much that she cannot submit Scandinavian nations to arms in self-defence to any more losses for the future. The issue against Germanic aggression, is not one of a of this contest is of vital importance to her recent date. -

Coastal Living in Denmark

To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Coastal living in Denmark © Daniel Overbeck - VisitNordsjælland To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. The land of endless beaches In Denmark, we look for a touch of magic in the ordinary, and we know that travel is more than ticking sights off a list. It’s about finding wonder in the things you see and the places you go. One of the wonders that we at VisitDenmark are particularly proud of is our nature. Denmark has wonderful beaches open to everyone, and nowhere in the nation are you ever more than 50km from the coast. s. 2 © Jill Christina Hansen To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Denmark and its regions Geography Travel distances Aalborg • The smallest of the Scandinavian • Copenhagen to Odense: Bornholm countries Under 2 hours by car • The southernmost of the • Odense to Aarhus: Under 2 Scandinavian countries hours by car • Only has a physical border with • Aarhus to Aalborg: Under 2 Germany hours by car • Denmark’s regions are: North, Mid, Jutland West and South Jutland, Funen, Aarhus Zealand, and North Zealand and Copenhagen Billund Facts Copenhagen • Video Introduction • Denmark’s currency is the Danish Kroner Odense • Tipping is not required Zealand • Most Danes speak fluent English Funen • Denmark is of the happiest countries in the world and Copenhagen is one of the world’s most liveable cities • Denmark is home of ‘Hygge’, New Nordic Cuisine, and LEGO® • Denmark is easily combined with other Nordic countries • Denmark is a safe country • Denmark is perfect for all types of travelers (family, romantic, nature, bicyclist dream, history/Vikings/Royalty) • Denmark has a population of 5.7 million people s. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Wood, Christopher Were the developments in 19th century small arms due to new concepts by the inventors and innovators in the fields, or were they in fact existing concepts made possible by the advances of the industrial revolution? Original Citation Wood, Christopher (2013) Were the developments in 19th century small arms due to new concepts by the inventors and innovators in the fields, or were they in fact existing concepts made possible by the advances of the industrial revolution? Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/19501/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Were the developments in 19th century small -

On Groundbreaking Innovations in Weapons Technology and the Long Wave

On groundbreaking innovations in weapons technology and the long wave DISSERTATION of the University of St. Gallen, School of Management, Economics, Law, Social Sciences and International Affairs to obtain the title of Doctor of Philosophy in Management submitted by Johannes Gerhard from Germany Approved on the application of Prof. Dr. Rainer Metz and Prof. Dr. Martin Hilb Dissertation no. 4769 Joh. Wagner & Söhne, Frankfurt, 2019 The University of St. Gallen, School of Management, Economics, Law, Social Sciences and International Affairs hereby consents to the printing of the present dissertation, without hereby expressing any opinion on the views herein expressed. St. Gallen, May, 22, 2018 The President: Prof. Dr. Thomas Bieger Dedicated to Nikolai Kondratieff I thank Professor Metz as well as Professor Hilb for their support and patience. Table of contents Table of contents I Table of figures VIII List of tables IX Table of abbreviations X Abstract XI Zusammenfassung XIII 1. Introductory part 1 1.1. Meaning for research and practice 3 1.1.1. Meaning for research 3 1.1.2. Meaning for practice 4 1.2. Objective 5 1.3. Procedure 5 2. General theoretical part 7 2.1. Theories related to the topic of this dissertation 9 2.1.1. Time frame of this dissertation and countries under analysis 9 2.1.2. The Kondratieff cycle 10 2.1.2.1. Predecessors and the meaning of Nikolai Kondratieff 10 2.1.2.2. The work of Nikolai Kondratieff 11 2.1.2.3. Critique regarding Kondratieff‟s work 11 2.1.2.4. Long waves in rolling returns of the S&P 500 from 1789 to 2017 13 2.1.3. -

Dominik Hünniger: Power, Economics and the Seasons

Dominik Hünniger: Power, Economics and the Seasons. Local Differences in the Per- ception of Cattle Plagues in 18th Century Schleswig and Holstein Paper presented at the Rural History 2013 conference, Berne, 19th to 22nd August 2013. DRAFT - please do not quote. 1. Introduction “Diseases are ideas“1 - this seemingly controversial phrase by Jacalyn Duffin will guide my presentation today. This is not to say that diseases do not take biological as well as historical reality. They most definitely do, but their biological „reality“ is embellished and interpreted by culture. Hence, the cultural and social factors influencing diagnoses, definitions and contain- ment strategies are the main focus of my paper.2 In particular, I will focus on how historical containment policies concerning epidemics and epizootics were closely intertwined with questions of power, co-operation and conflicts. One always had to consider and interpret different interests in order to find appropriate and fea- sible containment policies. Additionally all endeavours to regulate the usually very severe consequences of epidemics could be contested by different historical actors. In this respect, current research on the contested nature of laws and ordinances in Early Modern Europe es- tablished the notion of state building processes from below through interaction.3 In addition, knowledge and experience were locally specific and the attempts of authorities to establish norms could be understood and implemented in very idiosyncratic ways.4 Hence, implementation processes almost always triggered conflicts and misunderstandings. At the same time, authorities as well as subjects were interested in compromise and adjustments. Here, Stefan Brakensiek„s work is especially relevant for the interpretation of the events dur- ing a cattle plague outbreak in mid-18th-century Schleswig and Holstein: in particular his the- 1 Duffin, Lovers (2005), p. -

Common Eider Somateria M. Mollissima

Baltic/Wadden Sea Common Eider 167 Status of the Baltic/Wadden Sea population of the Common Eider Somateria m. mollissima M. Desholm1, T.K. Christensen1, G. Scheiffarth2, M. Hario3, Å. Andersson4, B. Ens5, C.J. Camphuysen6, L. Nilsson7, C.M. Waltho8, S-H. Lorentsen9, A. Kuresoo10, R.K.H. Kats5,11, D.M. Fleet12 & A.D. Fox1 'Department of Coastal Zone Ecology, National Environmental Research Institute, Grenåvej 12, 8410 Rønde, Denmark. Email: mde0dmu.dk/tk0dmu.dk/tfo0dmu.dk 2Institut für Vogelforschung, 'Vogelwarte Helgoland', An der Vogelwarte 21, D - 26386 Wilhelmshaven, Germany. Email: g.scheiffarthiat-online.de ‘Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, Söderskär Game Research Station. P.O.Box 6, FIN-00721 Helsinki. Finland. Email: martti.hario0rktl.fi ‘Ringgatan 39 C, S-752 17 Uppsala, Sweden. Email: ake_aSswipnet.se 5Alterra, P.O. Box 167, 1790 AD Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands. Email: b.j.ensØaIterra.wag-ur.nl/r.k.h.katsØalterra.wag-ur.nl ‘Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (Royal NIOZl, P.O. Box 59, 1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands. Email: kees.camphuysenldwxs.nl 'Department of Animal Ecology, University of Lund, Ecology Building, S-223 62 Lund, Sweden. Email: leif.nilssoniazooekol.lu.se “73 Stewart Street, Carluke, Lanarkshire, Scotland, UK, ML8 5BY. Email: clydeeider0aol.com 'Norwegian Institute for Nature Research. Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway Email: Shl0ninatrd.ninaniku.no '“Institute of Zoology and Botany, Riia St. 181, 51014, Tartu, Estonia. Email: akuresoo0zbi.ee "Department of Animal Ecology, University of Groningen, Kerklaan 30, 9751 NH, Groningen, The Netherlands. Email: r.k.h.kats0alterra.wag-ur.nl ,2Landesamt für den Nationalpark Schleswig-Holsteinisches Wattenmeer, Schlossgarten 1, D - 257832 Tönning, Germany. -

A Short Biography of Heinrich Witt*

A Short Biography of Heinrich Witt* Christa Wetzel The following short biography reconstructs Heinrich Witt’s life according to the information provided by his diary as well as from other sources. It is limited to presenting the main lines of the course of his life – in the full knowledge that any definition of a life’s “main lines” is already an interpretation. A common thread of the narration, apart from those personal data and events as one expects from a biography (birth, family, education, vocation, marriage, death), are the business activities of Heinrich Witt as a merchant. Thus, the description of his life gives a sketch of the economic and social networks characterizing the life, both mobile and settled, of Heinrich Witt as a migrant. However, this biography will not and cannot provide a detailed description of each of Witt’s business activities or of his everyday life or of the many people to which he had contact in Germany, Europe and Peru. Even if, according to Bourdieu, the course a life has taken cannot be grasped without knowledge of and constant reflection on the “Metro map”, this biography also does not give a comprehensive description of the period, i.e. of the political, economic, social and cultural events and discourses in Peru, Europe or, following Witt’s view, on the entire globe.1 Furthermore, this rather “outward” biography is not the place to give a reconstruction of Witt’s world of emotions or the way in which he saw and reflected on himself. All this will be left to the discoveries to be made when reading his diary.