Remembering the Schleswig War of 1864: a Turning Point in German and Danish National Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

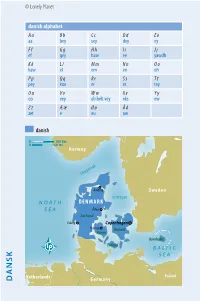

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

Department of Regional Health Research Faculty of Health Sciences - University of Southern Denmark

Department of Regional Health Research Faculty of Health Sciences - University of Southern Denmark The focus of Department of Regional Health Research, Region of Southern Denmark, and Region Zealand is on cooperating to create the best possible conditions for research and education. 1 Successful research environments with open doors With just 11 years of history, Department of Regional Health Research (IRS) is a relatively “The research in IRS is aimed at the treatment new yet, already unconditional success of the person as a whole and at the more experiencing growth in number of employees, publications and co-operations across hospitals, common diseases” professional groups, institutions and national borders. University partner for regional innovations. IRS is based on accomplished hospitals professionals all working towards improving The research in IRS is directed towards the man’s health and creating value for patients, person as a whole and towards the more citizens and the community by means of synergy common diseases. IRS reaches out beyond the and high professional and ethical standards. traditional approach to research and focusses on We largely focus on the good working the interdisciplinary and intersectoral approach. environment, equal rights and job satisfaction IRS makes up the university partner and among our employees. We make sure constantly organisational frame for clinical research and to support the delicate balance between clinical education at hospitals in Region of Southern work, research and teaching. Denmark* and Region Zealand**. Supports research and education Many land registers – great IRS continues working towards strengthening geographical spread research and education and towards bringing the There is a great geographical spread between the department and the researchers closer together hospitals, but research environments and in the future. -

The Li(Le Told Story of Scandanavia in the Dark Ages

The Vikings The Lile Told Story of Scandanavia in the Dark Ages The Viking (modern day Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes) seafaring excursions occurred from about 780 to 1070 AD. They started raiding and pillaging in the north BalCc region of Europe. By the mid 900s (10th century) they had established such a permanent presence across France and England that they were simply paid off (“Danegeld”) to cohabitate in peace. They conquered most of England, as the Romans had, but they did it in only 15 years! They formed legal systems in England that formed the basis of Brish Common Law, which at one Cme would later govern the majority of the world. They eventually adapted the western monarchy form of government, converted to ChrisCanity, and integrated into France, England, Germany, Italy, Russia, Syria, and out into the AtlanCc. They also brought ChrisCanity back to their home countries, set up monarchies, and forged the countries of Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and Russia. It was the direct descendant of the Vikings (from Normandy) who led the capture of Jerusalem during the First Crusade. The Romans dominated Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and England. They never could conquer the Germanic people to the north. The Germanic people sacked Rome three Cmes between 435 and 489 CE. Aer the Fall of Rome, a mass migraon of Germanic people occurred to the west (to France and England). The Frisians were at the center of a great trade route between the northern Germans (“Nordsman”) and bulk of Germanic peoples now in western Europe. High Tech in the 400s-700s The ships of the day were the hulk and the cog. -

Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein BONEBANK: a GERMAN- DANISH BIOBANK for STEM CELLS in BONE HEALING

Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein BONEBANK: A GERMAN- DANISH BIOBANK FOR STEM CELLS IN BONE HEALING ScanBalt Forum, Tallin, October 2017 PROJECT IN A NUTSHELL Start: 1th September 2015 End: 29 th February 2019 Duration: 36 months Total project budget: 2.377.265 EUR, 1.338.876 EUR of which are Interreg funding 3 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. Oktober 2017 PROJECT STRUCTURE Project Partners University Medical Centre Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck (Lead Partner) Odense University Hospital Stryker Trauma Soventec Life Science Nord Network partners Syddansk Sundhedsinnovation WelfareTech Project Management DSN – Connecting Knowledge 4 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. Oktober 2017 OPPORTUNITIES, AMBITION AND GOALS • Research on stem cells is driving regenerative medicine • Availability of high-quality bone marrow stem cells for patients and research is limited today • Innovative approach to harvest bone marrow stem cells during routine operations for fracture treatment • Facilitating access to bone marrow stem cells and driving research and innovation in Germany- Denmark Harvesting of bone marrow stem cells during routine operations in the university hospitals Odense and Lübeck Cross-border biobank for bone marrow stem cells located in Odense and Lübeck Organisational and exploitation model for the Danish-German biobank providing access to bone marrow stem cells for donators, patients, public research and companies 5 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. Oktober 2017 ACHIEVEMENTS SO FAR Harvesting of 53 samples, both in Denmark and Germany Donors/Patients Most patients (34) are over 60 years old 19 women 17 women Germany Isolation of stem cells possible Denmark 7 men 10 men Characterization profiles of stem cells vary from individual to individual Age < 60 years > 60 years 27 7 9 10 women men 6 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. -

Status of the Baltic/Wadden Sea Population of the Common Eider Somateria M

Baltic/Wadden Sea Common Eider 167 Status of the Baltic/Wadden Sea population of the Common Eider Somateria m. mollissima M. Desholm1, T.K. Christensen1, G. Scheiffarth2, M. Hario3, Å. Andersson4, B. Ens5, C.J. Camphuysen6, L. Nilsson7, C.M. Waltho8, S-H. Lorentsen9, A. Kuresoo10, R.K.H. Kats5,11, D.M. Fleet12 & A.D. Fox1 1Department of Coastal Zone Ecology, National Environmental Research Institute, Grenåvej 12, 8410 Rønde, Denmark. Email: [email protected]/[email protected]/[email protected] 2Institut für Vogelforschung, ‘Vogelwarte Helgoland’, An der Vogelwarte 21, D - 26386 Wilhelmshaven, Germany. Email: [email protected] 3Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, Söderskär Game Research Station. P.O.Box 6, FIN-00721 Helsinki, Finland. Email: [email protected] 4Ringgatan 39 C, S-752 17 Uppsala, Sweden. Email: [email protected] 5Alterra, P.O. Box 167, 1790 AD Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands. Email:[email protected]/[email protected] 6Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (Royal NIOZ), P.O. Box 59, 1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands. Email: [email protected] 7Department of Animal Ecology, University of Lund, Ecology Building, S-223 62 Lund, Sweden. Email: [email protected] 873 Stewart Street, Carluke, Lanarkshire, Scotland, UK, ML8 5BY. Email: [email protected] 9Norwegian Institute for Nature Research. Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway Email: [email protected] 10Institute of Zoology and Botany, Riia St. 181, 51014, Tartu, Estonia. Email: [email protected] 11Department of Animal Ecology, University of Groningen, Kerklaan 30, 9751 NH, Groningen, The Netherlands. -

City-Apartment Am Südhafen Kappeln (Schlei)

City-Apartment am Südhafen Kappeln (Schlei) Anja und Bernhard Gummert Bahnhofsweg 14, 24376 Kappeln Schlei Tel.: 0151 – 438 107 12 [email protected] www.city-apartment-kappeln.de Ortsbeschreibung Die idyllische Hafenstadt Kappeln, gelegen an Schlei und Ostsee, ist ein staatlich anerkannter Erholungsort und unter anderem auch durch die ZDF-Serie "Der Landarzt" als Filmort „Deekelsen" bekannt. Kappeln liegt zwischen der Landeshauptstadt Kiel und der maritimen Hafenstadt Flensburg im wunderschönen Urlaubsland Schleswig-Holstein direkt an der Schlei. Eingebettet in einer sanften Hügellandschaft nahe der Ostsee liegt Kappeln in einer Urlaubsregion, die ideale Bedingungen für die unterschiedlichsten Aktivitäten an Land und zu Wasser bietet. Mit ihrem Yachthafen ist sie ein beliebtes Ausflugsziel nicht nur für Segler und Wassersportler. Mit ihren Sehenswürdigkeiten, dem reizvollen Hafen und der attraktiven Fußgängerzone lädt Kappeln zum Verweilen ein. Die bunte Geschäftswelt und die gemütlichen Restaurants und Cafés sorgen für einen angenehmen und abwechslungsreichen Aufenthalt. Regelmäßig verkehrende Ausflugsschiffe bringen Sie u.a. zur Lotseninsel Schleimünde, nach Arnis der kleinsten Stadt Deutschlands und an sehenswerte Stellen an der Schlei. Für Gäste, die das Strandleben bevorzugen, bietet sich der nur wenige Kilometer entfernten und sehr gepflegten Ostseestrand in Weidefeld an, der durch einen abgeteilten Strandabschnitt auch bei Surfern hoch im Kurs steht. Freizeitangebote in und um Kappeln Fahrradverleih direkt im Zentrum und am -

Beowulf Timeline

Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Geatland. Beowulf was Beowulf’s Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of funeral. Grendel. to Denmark the Geats. Beowulf fought Heorot lay silent. the dragon. 1. Stick Text Here 3. Stick Text Here 5. Stick Text Here 7. Stick Text Here 9. Stick Text Here 2. Stick Text Here 4. Stick Text Here 6. Stick Text Here 8. Stick Text Here 10. Stick Text Here Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Write an extra sentence or two about each event. 4. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Geatland. Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Beowulf was Beowulf’s funeral. Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of Grendel. -

Declining Homogamy of Austrian-German Nobility in the 20Th Century? a Comparison with the Dutch Nobility Dronkers, Jaap

www.ssoar.info Declining homogamy of Austrian-German nobility in the 20th century? A comparison with the Dutch nobility Dronkers, Jaap Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Dronkers, J. (2008). Declining homogamy of Austrian-German nobility in the 20th century? A comparison with the Dutch nobility. Historical Social Research, 33(2), 262-284. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.33.2008.2.262-284 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-191342 Declining Homogamy of Austrian-German Nobility in the 20th Century? A Comparison with the Dutch Nobility Jaap Dronkers ∗ Abstract: Has the Austrian-German nobility had the same high degree of no- ble homogamy during the 20th century as the Dutch nobility? Noble homog- amy among the Dutch nobility was one of the two main reasons for their ‘con- stant noble advantage’ in obtaining elite positions during the 20th century. The Dutch on the one hand and the Austrian-German nobility on the other can be seen as two extreme cases within the European nobility. The Dutch nobility seems to have had a lower degree of noble homogamy during the 20th century than the Austrian-German nobility. -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

Evidence from Hamburg's Import Trade, Eightee

Economic History Working Papers No: 266/2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Economic History Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, London, UK. T: +44 (0) 20 7955 7084. F: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY WORKING PAPERS NO. 266 – AUGUST 2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Email: [email protected] Abstract The study combines information on some 180,000 import declarations for 36 years in 1733–1798 with published prices for forty-odd commodities to produce aggregate and commodity specific estimates of import quantities in Hamburg’s overseas trade. In order to explain the trajectory of imports of specific commodities estimates of simple import demand functions are carried out. Since Hamburg constituted the principal German sea port already at that time, information on its imports can be used to derive tentative statements on the aggregate evolution of Germany’s foreign trade. The main results are as follows: Import quantities grew at an average rate of at least 0.7 per cent between 1736 and 1794, which is a bit faster than the increase of population and GDP, implying an increase in openness. Relative import prices did not fall, which suggests that innovations in transport technology and improvement of business practices played no role in overseas trade growth. -

Wars Between the Danes and Germans, for the Possession Of

DD 491 •S68 K7 Copy 1 WARS BETWKEX THE DANES AND GERMANS. »OR TllR POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. BV t>K()F. ADOLPHUS L. KOEPPEN FROM THE "AMERICAN REVIEW" FOR NOVEMBER, U48. — ; WAKS BETWEEN THE DANES AND GERMANS, ^^^^ ' Ay o FOR THE POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. > XV / PART FIRST. li>t^^/ On feint d'ignorer que le Slesvig est une ancienne partie integTante de la Monarchie Danoise dont I'union indissoluble avec la couronne de Danemarc est consacree par les garanties solennelles des grandes Puissances de I'Eui'ope, et ou la langue et la nationalite Danoises existent depuis les temps les et entier, J)lus recules. On voudrait se cacher a soi-meme au monde qu'une grande partie de la popu- ation du Slesvig reste attacliee, avec une fidelite incbranlable, aux liens fondamentaux unissant le pays avec le Danemarc, et que cette population a constamment proteste de la maniere la plus ener- gique centre une incorporation dans la confederation Germanique, incorporation qu'on pretend medier moyennant une armee de ciuquante mille hommes ! Semi-official article. The political question with regard to the ic nation blind to the evidences of history, relations of the duchies of Schleswig and faith, and justice. Holstein to the kingdom of Denmark,which The Dano-Germanic contest is still at the present time has excited so great a going on : Denmark cannot yield ; she has movement in the North, and called the already lost so much that she cannot submit Scandinavian nations to arms in self-defence to any more losses for the future. The issue against Germanic aggression, is not one of a of this contest is of vital importance to her recent date.