Comparison of Specific Properties of Engineering Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High-Strength Aluminum P/M Alloys

ASM Handbook, Volume 2: Properties and Selection: Nonferrous Alloys and Special-Purpose Materials Copyright © 1990 ASM International® ASM Handbook Committee, p 200-215 All rights reserved. DOI: 10.1361/asmhba0001064 www.asminternational.org High-Strength Aluminum P/M Alloys J.R. Pickens, Martin Marietta Laboratories POWDER METALLURGY (P/M) tech- one of the dominant structural material fam- of particular concern to designers of aircraft nology provides a useful means of fabricating ilies of the 20th century. Aluminum has low and aerospace structures, where high ser- net-shape components that enables machin- density (2.71 g/cm 3) compared with compet- vice temperatures preclude the use of alu- ing to be minimized, thereby reducing costs. itive metallic alloy systems, good inherent minum alloys for certain structural compo- Aluminum P/M alloys can therefore compete corrosion resistance because of the contin- nents. with conventional aluminum casting alloys, uous, protective oxide film that forms very The number of alloying elements that as well as with other materials, for cost- quickly in air, and good workability that have extensive solid solubility in aluminum critical applications. In addition, P/M technol- enables aluminum and its alloys to be eco- is relatively low. Consequently, there are ogy can be used to refine microstructures nomically rolled, extruded, or forged into not many precipitation-hardenable alumi- compared with those made by conventional useful shapes. Major alloying additions to num alloy systems that are practical by ingot metallurgy (I/M), which often results in aluminum such as copper, magnesium, conventional I/M. This can be viewed as a improved mechanical and corrosion proper- zinc, and lithium--alone, or in various limitation when alloy developers endeavor ties. -

Tensile Strength of C/C Composites

16 TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPOSITE MATERIALS TENSILE STRENGTH OF C/C COMPOSITES Jun Koyanagi*, Hiroshi Hatta*, Yasuo Kogo**, Ichiro Shiota*** *Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, **Department of Materials Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science *** Department of Materials Science and Technology, Kogakuin University Keywords : C/C composites, tensile strength, fracture mechanism ABSTRACT changing heat treatment temperature, and the tensile Fracture mechanism and model based on it in strength and interfacial strength were measured. In Carbon-carbon composites are studied. Interfacial addition, comparing these results with their fracture strength between reinforcing fiber and matrix is a patterns, a tensile fracture model of C/Cs was potential candidate governing the tensile fracture of proposed. C/Cs. However, The mechanisms connecting the tensile strength and the factor have not yet been 2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE clarified. In the present study, tensile fracture 2.1 Materials patterns of various C/C composites with changing Two types of C/Cs were examined. These the interfacial strength were observed in detail, and C/Cs were different only in their reinforcing fibers, a fundamental tensile fracture model of C/C K321 and K633 by Mitsubishi Sanshi Co. Japan. composites in accordance with the experimental These fibers were fabricated from the same observations were proposed. The analytical result precursor but differed only in HTT. Hereafter, the shows reasonable agreement with the experimental C/Cs reinforced with K321 and K633 will be results, and verifies that the fracture mechanism is referred to as K321-C/C and K633-C/C, respectively. consistent. Both C/Cs were of a symmetric 0°/90° cross-ply lamination, fabricated from carbon fiber reinforced phenolic resin matrix composites, CFRPs, with a 1. -

ANNEX III Restricted Nuclear Goods, Commodities, and Technologies

ANNEX III* Restricted Nuclear Goods, Commodities, and Technologies Pursuant to paragraph 5 (b) of resolution 2087 (2013), the items contained in this document are subject to the provisions of paragraph 8 (a), 8 (b) and 8 (c) of resolution 1718 (2006) under the DPRK sanctions regime; and pursuant to resolution 1929 (2010) under the Iran sanctions regime (corresponding with document INFCIRC/254/Rev.11/Part1‐1) * Annex III to Enrico Carisch and Loraine Rickard-Martin, “United Nations Sanctions on Iran and North Korea: An Implementation Manual,” New York: International Peace Institute. March 2014. UN Sanctions on Iran and North Korea SPECIAL FISSIONABLE MATERIAL INFCIRC/254/Rev.11/Part1 ANNEX B Plutonium-239 For plutonium to reach this state it has to be processed from U-238. Plutonium in this form has gone through a nuclear reactor. Varies based on level of enrichment and portion of Pu-240 inherent in the metal. ~5 kg of very pure Pu- 239 is enough for a strategic nuclear weapon. This metal is extremely heavy per unit of volume. This is a radioactive isotope of plutonium; it generally will be transported in ways to minimize radioactive exposure—lead-lined containers, etc. Uranium-233 Made from thorium-232. It has never been used to generate power or in nuclear weapons, but it has been used in research reactors. Production costs alone have been estimated at 2–4 million per kilogram during the Cold War. This metal is extremely heavy per unit of volume. This is a radioactive isotope of uranium; it generally will be transported in ways to minimize radioactive exposure—lead-lined containers, etc. -

A Study of the Mechanical Properties of Composite Materials with a Dammar-Based Hybrid Matrix and Two Types of Flax Fabric Reinforcement

polymers Article A Study of the Mechanical Properties of Composite Materials with a Dammar-Based Hybrid Matrix and Two Types of Flax Fabric Reinforcement Dumitru Bolcu † and Marius Marinel St˘anescu*,† Department of Mechanics, University of Craiova, 165 Calea Bucure¸sti,200620 Craiova, Romania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +40-740-355-079 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 7 July 2020; Accepted: 22 July 2020; Published: 24 July 2020 Abstract: The need to protect the environment has generated, in the past decade, a competition at the producers’ level to use, as much as possible, natural materials, which are biodegradable and compostable. This trend and the composite materials have undergone a spectacular development of the natural components. Starting from these tendencies we have made and studied from the point of view of mechanical and chemical properties composite materials with three types of hybrid matrix based on the Dammar natural hybrid resin and two types of reinforcers made of flax fabric. We have researched the mechanical properties of these composite materials based on their tensile strength and vibration behavior, respectively. We have determined the characteristic curves, elasticity modulus, tensile strength, elongation at break, specific frequency and damping factor. Using SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) analysis we have obtained images of the breaking area for each sample that underwent a tensile test and, by applying FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) and EDS (Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy) analyzes, we have determined the spectrum bands and the chemical composition diagram of the samples taken from the hybrid resins used as a matrix for the composite materials under study. -

Space Elevator a New Way to Gain Orbit Adil Oubou 5/3/2014

Space Elevator A New Way To Gain Orbit Adil Oubou 5/3/2014 Abstract After 56 years of great space exploration, the space flight program found itself asking an intriguing question: What’s next? Should humans constrain the space program to low Earth orbit, revisit the moon, or simply go beyond anything they have done before? No matter what the next step is, there is a great need for a reliable, safe, affordable and easy method of gaining orbit. The space elevator concept discussed in this report, based on the design provided in Peter Swan’s book “Space Elevators: An Assessment of the Technological Feasibility and the Way Forward“, shines the light on an economically and technologically feasible solution within the next two decades that will lift payloads including humans from the earth’s surface into space at a greater capacity than current rockets while significantly lowering cost to $500/kg. The system design includes a tether line that extends from the Earth’s surface to an altitude of 100,000 km that utilizes electrical motor driven climbers to gain orbit. The success feasibility of this space flight system is highly dependent on the development of Carbon Nanotube (CNT) material, which will provide high strength and low mass properties for the space elevator system components to withstand environmental and operational stresses. Table of Contents 1.0 The New Way to Orbit ....................................................................................................... 4 2.0 Why Space Elevator? ........................................................................................................ -

Reinforcements—The Key to High Performance Composite Materials

^_ a ^-9I NASA Technical Memorandum 103230 Reinforcements—The Key to High Performance Composite Materials Salvatore J. Grisaffe Lewis Research Center Cleveland, Ohio Prepared for the Complex Composites Workshop sponsored by the Japanese Technology Evaluation Center Washington, DC, March 27, 1990 NASA REINFORCEMENTS - THE KEY TO HIGH-PERFORMANCE COMPOSITE MATERIALS Salvatore J. Grisaffe National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lewis Research Center Cleveland, Ohio 44135 INTRODUCTION High-temperature reinforcements are the key to high-performance composite materials. Such materials are the critical enabling technological issue in the design and development of 21st-century aerospace propulsion and power systems. The purpose of this section is to review some of the insights and findings developed on Japanese fibers and whiskers during the Japanese Technology Evalu- ation Center (JTEC) one-week visit to Japan and to examine these in light of current U.S. fiber technology. Conventional materials are too heavy to provide effective structural mem- bers for future flight systems. The estimated cost of moving 1 pound to orbit is about $1000; cost per pound to the Noon is about $50,000; and cost per pound to Mars is about $500,000. Thus, the payoff for low-density, high-strength fibers and composites becomes clear. Figure 1 shows how high-performance com- posites could generally benefit any future high-speed civil transport aircraft. NOx intrusion and noise must be overcome before such an aircraft can be consid- ered feasible. Minimal environmental intrusion is contingent on combustors that can operate at extremely high temperatures and so , must ,be constructed of, for example, ceramic matrix composites. -

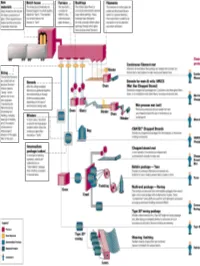

All About Fibers

RawRaw MaterialsMaterials ¾ More than half the mix is silica sand, the basic building block of any glass. ¾ Other ingredients are borates and trace amounts of specialty chemicals. Return © 2003, P. Joyce BatchBatch HouseHouse && FurnaceFurnace ¾ The materials are blended together in a bulk quantity, called the "batch." ¾ The blended mix is then fed into the furnace or "tank." ¾ The temperature is so high that the sand and other ingredients dissolve into molten glass. Return © 2003, P. Joyce BushingsBushings ¾The molten glass flows to numerous high heat-resistant platinum trays which have thousands of small, precisely drilled tubular openings, called "bushings." Return © 2003, P. Joyce FilamentsFilaments ¾This thin stream of molten glass is pulled and attenuated (drawn down) to a precise diameter, then quenched or cooled by air and water to fix this diameter and create a filament. Return © 2003, P. Joyce SizingSizing ¾The hair-like filaments are coated with an aqueous chemical mixture called a "sizing," which serves two main purposes: 1) protecting the filaments from each other during processing and handling, and 2) ensuring good adhesion of the glass fiber to the resin. Return © 2003, P. Joyce WindersWinders ¾ In most cases, the strand is wound onto high-speed winders which collect the continuous fiber glass into balls or "doffs.“ Single end roving ¾ Most of these packages are shipped directly to customers for such processes as pultrusion and filament winding. ¾ Doffs are heated in an oven to dry the chemical sizing. Return © 2003, P. Joyce IntermediateIntermediate PackagePackage ¾ In one type of winding operation, strands are collected into an "intermediate" package that is further processed in one of several ways. -

Applications of an Aluminum-Beryllium Composite for Structural Aerospace Components

Applications of an Aluminum -Beryllium Composite for Structural Aerospace Components William Speer and Omar S. Es -Said Mechanical Engineering Department, Loyola Marymount University, 7900 Loyola Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90045 -8145, USA Abstract The us e of AlBeMet AM162, an aluminum -beryllium metal matrix composite, is an effective way to reduce the size and weight of many structural aerospace components that are currently made out of aluminum and titanium alloys. These savings, which are essential for today’s technologies, are primarily due to the material’s high modulus and low density combined with its better than average specific strength. The raw material costs are significantly higher than they are for traditional engineering alloys, and the avai lable billet sizes are more limited than they are for aluminum and titanium alloys. Although the material costs are higher for the aluminum -beryllium composite, ease of machining makes it financially competitive when compared to equivalent parts made out of titanium alloys. Due to toxic nature of beryllium, however, debris -generating operations must be strictly regulated to limit worker’s exposure to the material and protect them from potentially fatal diseases. Keywords: Metal matrix; AlBeMet; High el astic modulus; Low density; Weight reduction; Stiffness -driven design 1. Introduction The aerospace industry is continually searching for ways to reduce the weight of its products and maximize the amount of profit -making payload in launch vehicles. One o f the most common ways engineers reduce weight is to make their products out of low-density alloys or engineering composites. These materials offer very high strength and/or stiffness to weight ratios; therefore, they require less mass and take less space to support a given load in comparison to other material choices. -

Research on Laser-TIG Hybrid Welding of 6061-T6 Aluminum Alloys Joint and Post Heat Treatment

metals Article Research on Laser-TIG Hybrid Welding of 6061-T6 Aluminum Alloys Joint and Post Heat Treatment Hongyang Wang * , Xiaohong Liu and Liming Liu Key Laboratory of Liaoning Advanced Welding and Joining Technology & School of Materials Science and Engineering, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian 116024, China; [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (L.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 22 November 2019; Accepted: 7 January 2020; Published: 15 January 2020 Abstract: The 6061-T6 aluminum (Al) alloys was joined by the laser induced tungsten inert gas (TIG) hybrid welding technique. It mainly studied the influences of welding parameters, solution, and aging (STA) treatment on the microstructure and tensile properties of Al alloy hybrid welding joints. Microstructures of the joints were also analyzed by optical microscopy and transmission electron microscopy. Results showed that the laser induced arc hybrid welding source changed the microstructure of the fusion zone and heat effect zone. STA treatment effectively improved the mechanical properties of the softening area in the hybrid welding joint, whose values of the tensile strength and elongation were on average 286 MPa and 20.5%. The distribution of the reinforcement phases and dislocations distributed were more uniform, which improved the property of STA treated joint. Keywords: Al alloy; laser induced arc hybrid welding; heat treatment; microstructure 1. Introduction Aluminum alloys are used as structural materials, due to the high strength, excellent corrosion resistance, and low density, which makes them promising alternatives to steels for lightweight structures such as vehicles and airplanes [1–7]. Aluminum alloys are also extensively used in aviation, vessel, and electronics industries due to their light weight, high specific strength, good corrosion resistance, and excellent mechanical properties [8–16]. -

Controls the Level of Power in the Core, and the Components Which Normally Contain, Come Into Direct Contact with Or Control the Primary Coolant of the Reactor Core;

Document Generated: 2019-11-16 Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. SCHEDULE 1 PROHIBITED GOODS PART III GROUP 2 ATOMIC ENERGY MINERALS AND MATERIALS AND NUCLEAR FACILITIES, EQUIPMENT, APPLIANCES AND SOFTWARE Interpretations and definitions In this Group: “boron equivalent” (BE) is defined as: BE = CF × Concentration of element Z in ppm and gammaB and gammaZ are the thermal neutron capture cross sections (in barns) for boron and element Z respectively; and AB and AZ are the atomic weights of boron and element Z respectively; “depleted uranium” means uranium depleted in the isotope 235 below that occurring in nature; “effective gramme” of special fissile material or other fissile material means: a. for plutonium isotopes and uranium-233, the isotope weight in grammes; b. for uranium enriched 1 per cent or greater in the isotope U-235, the element weight in grammes multiplied by the square of its enrichment expressed as a decimal weight fraction; c. for uranium enriched below 1 per cent in the isotope U-235, the element weight in grammes multiplied by 0.0001; d. for americium-242m, curium-245 and curium-247, californium-249 and californium-251, the isotope weight in grammes multiplied by 10; “fibrous or filamentary materials” include: a. continuous monofilaments; b. continuous yarns and rovings; c. tapes, fabrics, random mats and braids; d. chopped fibres, staple fibres and coherent fibre blankets; e. whiskers, either monocrystalline -

A Review of Metastable Beta Titanium Alloys

metals Review A Review of Metastable Beta Titanium Alloys R. Prakash Kolli 1,* ID and Arun Devaraj 2 1 Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA 2 Physical and Computational Sciences Directorate, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA 99354, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-301-405-5217; Fax: 301-405-6327 Received: 21 May 2018; Accepted: 25 June 2018; Published: 30 June 2018 Abstract: In this article, we provide a broad and extensive review of beta titanium alloys. Beta titanium alloys are an important class of alloys that have found use in demanding applications such as aircraft structures and engines, and orthopedic and orthodontic implants. Their high strength, good corrosion resistance, excellent biocompatibility, and ease of fabrication provide significant advantages compared to other high performance alloys. The body-centered cubic (bcc) b-phase is metastable at temperatures below the beta transus temperature, providing these alloys with a wide range of microstructures and mechanical properties through processing and heat treatment. One attribute important for biomedical applications is the ability to adjust the modulus of elasticity through alloying and altering phase volume fractions. Furthermore, since these alloys are metastable, they experience stress-induced transformations in response to deformation. The attributes of these alloys make them the subject of many recent studies. In addition, researchers are pursuing development of new metastable and near-beta Ti alloys for advanced applications. In this article, we review several important topics of these alloys including phase stability, development history, thermo-mechanical processing and heat treatment, and stress-induced transformations. -

Fatigue of Ti-6Al-4V

Chapter 3 Fatigue of Ti-6Al-4V Shabnam Hosseini Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/45753 1. Introduction Metallic biomaterials have essentially three fields of use; these are the artificial hip joints, screw, plates and nails for internal fixation of fractures, and dental implants. Any of these devices must support high mechanical load and resistance of material against breakage is essential. High mechanical properties are needed for structural efficiency of surgical and dental implants. But their volume is restricted by anatomic realities what require good yield and fatigue strengths of metal [1]. The use of titanium alloys is due to their excellent corrosion resistance. Also, that is because of their tensile strength, a high strength to weight ratio and low elastic modulus. Titanium continues to be widely used in biomedical applications. Ti-6Al-4V alloy is the most frequently used these days [2]. Fatigue fracture and wear have been identified as some of the major problems associated with implant loosening, stress-shielding and ultimate implant failure. Although wear is commonly reported in orthopedic applications such as knee and hip joint prostheses, it is also a serious and often fatal experience in mechanical heart valves. Fig.1 illustrates some examples of fatigue fracture of implant devices in the hip prosthesis and a mechanical heart valve. It can be seen that fatigue-wear interaction plays a significant role in ultimate failure of these medical devices [3]. In orthopedic implants design, it is unavoidable the presence of geometrical fillets such as notches which cause stress locally.