Impacts Impacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Msa S1879 000004.Pdf

I * t I t / ^ t J r i t I t i * t 8 i I8 s B roin 9 ro b 0 D z zi B m • o o X 8 X 9 m m o n o x 71 m 3 m o m o o c z I. Iz B s a D o 8 D ft M ft s CO a CO 3. o ^• • n O o c ft 3 4 < I c j z "11 ri 51 u > o l:! s n k !:i v Tl B -i en I o 03 S. 8 X in in m a U |'J f o < (i:) z 1 1 i> i o <: < T n n 71 it rr in g 8 o 8 M Q 5 Q q 3 O n CD (D -%O (Q <D «)' • o O o C 3 i ro i tlLlMiiMl lil.t > r w o O O c 10 H SL a o o o c 3 ofo 1996 OFFICE OF BRIDGE DEVELOPMENT BRIDGE INVE NTO BRIDGE NO. 21038 MD ROUTE 68 OVER ANTIETAM CREEK WASHINGTON COUNTY AMERICAN CONCRETE INSTITUTE - MO CHAPTER EXCELLENCE IN CONCRETE AWARD 1995 - 1996 AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CIVIL ENGINEERS - MD CHAPTER OUTSTANDING CIVIL ENGINEERING ACHIEVEMENT 1995 - 1996 Mary/and Department of Transportation STATE HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION NOTES AND DEBNmOMS LEGEND DEHNFTION FOR A BRIDGE ANY STSUCTURE (BRIDGE , BOX CULVERT, BATTERT Of PIPES) THAT HAS A LENGTH GREATER THAN 20 FEET MEASURED ALONG THE CENTERUNE OF HIGHWAY. ACCMP AsphoHCeatod Comigatad MvtatPip* AG Aiuminum Gira«r DEFINrtlON OF SINGLE SINGLE STRUCTURE: ANY BRIDE WHICH CARRIES A SINGLE ROADWAY OR DUAL ROADWAY ON WHICH AND DUAL STRUCTURES: THE MEDIAN AREA IS CLOSED, SHALL BE CONSIDERED A SINGLE BRIDGE. -

THE FLOODS of MARCH 1936 Part 1

If you do jno*-Be <l this report after it has served your purpose, please return it to the Geolocical -"" Survey, using the official mailing label at the end UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR THE FLOODS OF MARCH 1936 Part 1. NEW ENGLAND RIVERS Prepared in cooperation withihe FEDERAL EMERGENCY ADMINISTRATION OF PUBLIC WORKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 798 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Water-Supply Paper 798 THS^LOODS OF MARCH 1936 PART 1. NEW ENGLAND RIVERS NATHAN C. GROVER Chief Hydraulic Engineer Prepared in cooperation with the FEDERAL EMERGENCY ADMINISTRATION OF PUBLIC WORKS UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1937 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 70 cents CONTENTS Page Abstract............................................................. 1 Introduction......................................................... 2 Authorization........................................................ 5 Administration and personnel......................................... 5 Acknowledgments...................................................... 6 General features of the storms....................................... 7 Floods of the New England rivers....................................o 12 Meteorologic and hydrologic conditions............................... 25 Precipitation records............................................ 25 General f>!-................................................... 25 Distr<* '-utlon -

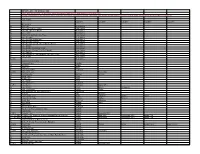

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an Asterisk * Do Not Have Depth Information and Appear with Improvised Contour Lines County Information Is for Reference Only

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an asterisk * do not have depth information and appear with improvised contour lines County information is for reference only. Your lake will not be split up by county. The whole lake will be shown unless specified next to name eg (Northern Section) (Near Follette) etc. LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake St Clair Great Lakes GL (MI) Great Lakes Cedar Creek Reservoir AL Deerwood Lake Franklin AL Dog River Shelby AL Gantt Lake Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Covington AL (GA) Guntersville Lake Lee Harris (GA) AL Highland Lake * Marshall Jackson AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Jordan Lake Blount AL Lake Gantt * Elmore AL Lake Jackson * Covington AL (FL) Lake Martin Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Mitchell Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Chilton Coosa AL Lake Wedowee (RL Harris Reservoir) Tuscaloosa AL Lay Lake Clay Randolph AL Lewis Smith Lake * Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Logan Martin Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Mobile Bay Saint Clair Talladega AL Ono Island Baldwin Mobile AL Open Pond * Baldwin AL Orange Beach East Covington AL Bon Secour River and Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin AL (FL) Pickwick Lake Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL (TN) (MS) Pickwick Lake (Northern Section, Pickwick Dam to Waterloo) Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL (TN) (MS) Shelby Lakes Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Tallapoosa River at Fort Toulouse * Baldwin AL Walter F. -

Charted Lakes List

LAKE LIST United States and Canada Bull Shoals, Marion (AR), HD Powell, Coconino (AZ), HD Gull, Mono Baxter (AR), Taney (MO), Garfield (UT), Kane (UT), San H. V. Eastman, Madera Ozark (MO) Juan (UT) Harry L. Englebright, Yuba, Chanute, Sharp Saguaro, Maricopa HD Nevada Chicot, Chicot HD Soldier Annex, Coconino Havasu, Mohave (AZ), La Paz HD UNITED STATES Coronado, Saline St. Clair, Pinal (AZ), San Bernardino (CA) Cortez, Garland Sunrise, Apache Hell Hole Reservoir, Placer Cox Creek, Grant Theodore Roosevelt, Gila HD Henshaw, San Diego HD ALABAMA Crown, Izard Topock Marsh, Mohave Hensley, Madera Dardanelle, Pope HD Upper Mary, Coconino Huntington, Fresno De Gray, Clark HD Icehouse Reservior, El Dorado Bankhead, Tuscaloosa HD Indian Creek Reservoir, Barbour County, Barbour De Queen, Sevier CALIFORNIA Alpine Big Creek, Mobile HD DeSoto, Garland Diamond, Izard Indian Valley Reservoir, Lake Catoma, Cullman Isabella, Kern HD Cedar Creek, Franklin Erling, Lafayette Almaden Reservoir, Santa Jackson Meadows Reservoir, Clay County, Clay Fayetteville, Washington Clara Sierra, Nevada Demopolis, Marengo HD Gillham, Howard Almanor, Plumas HD Jenkinson, El Dorado Gantt, Covington HD Greers Ferry, Cleburne HD Amador, Amador HD Greeson, Pike HD Jennings, San Diego Guntersville, Marshall HD Antelope, Plumas Hamilton, Garland HD Kaweah, Tulare HD H. Neely Henry, Calhoun, St. HD Arrowhead, Crow Wing HD Lake of the Pines, Nevada Clair, Etowah Hinkle, Scott Barrett, San Diego Lewiston, Trinity Holt Reservoir, Tuscaloosa HD Maumelle, Pulaski HD Bear Reservoir, -

DRAFT Wicomico River

Final Wicomico River Watershed Management Plan - Updated April 2014 PREPARED FOR: PREPARED BY: 8390 Main Street, 2nd Floor Ellicott City, MD 21043 www.cwp.org This page has intentionally been left blank. Wicomico River Watershed Management Plan Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................ viii SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 1 1.1 Process for Developing the Wicomico Watershed Management Plan ..................... 1 1.2 U.S. EPA Watershed Planning “A-I Criteria” ......................................................... 2 1.3 Plan Organization .................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Caveats .................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION 2. WATERSHED CHARACTERIZATION .............................................. 5 2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Stream Conditions ................................................................................................. 9 2.2.1 Total Maximum Daily Loads......................................................................... 10 2.2.2 Biological Conditions .................................................................................... 12 2.2.3 Water Quality Conditions ............................................................................. -

Wicomico County

2016 Calendar Year HIGHWAY LOCATION REFERENCE ALL INTERSECTIONS Data as of December 31, 2016 WICOMICO COUNTY SHA DISTRICT #1 WI The information in these maps is provided as a public service LEGEND by the Maryland State Highway Administration (MSHA). BG313 NOTICE E!95 Interstate Highway Restriction of Liability: SHA makes no claims, promises or guarantees about 348 BG the accuracy, completeness, or adequacy of the contents D AND S (1 US Highway L T / Y A R of these maps and expressly disclaims liability for any errors AR TE M MD 813-F and omissions in the contents of these documents. For more detailed maps, please contact: Kevin Powers of the N SHARPTOWN G[8 State Highway Data Services Division at 410-545-5518 or W by email at [email protected]. O H T IG N H IO P W AT AY TR R ADMINIS A H S 0/50 Y 313 MD 731-C BG T BG54 N R R DEL MA D U BG54 DELAWARE O C 50 E LINE RD MD 731-A MARDELA 0/ MD 675-B BG54 O W R SPRINGS C E E A DELMAR N D O T R 13 R S 0/ C E G O A 353 E H HEBRON R BG T C E O S W B T R A Y M BG347 U E O 50 US 50-UA G BG670 R D 0/ 0/50 D PITTSVILLE R BG346 WILLARDS BUS 0/13 RD MD 992-D BG346 Y O BUS 50 AN CIT C 13 OCE I SALISBURY 0/ 0/ WAY T 50 GATE N N A 0/ BG346 CEA 50 U O 0/ Q MD 815 OLD MD 992-E 50 MD 992-B MD 992-C D BG349 0/ R BG354 BG347 MD 991 MD 992-A E L L 350 I BG C M V RD T H L O E 349 ERM K BG BG12 ON L O RD E U C W I N T 13 O P N 0/ T A 350 N S BG Y D BG352 FRUITLAND N R BUS O W BG374 13 BG513 H EN 0/ IL AV L EH IT BG349 H R BG354 W D US 13-A 13 BG352 0/ BG12 BG349 WICOMICO COUNTY Y NT HIGHWAY LOCATION REFERENCE -

DIVISION of WATER POLLUTION CONTROL Thomas C.· Mcmahon, Director COMPILATIONOF LAKES, PONDS, and RESERVOIRS

Compi lotion of Lakes, Ponds, and Reservoirs Relative to . THE MASSACHUSETTS LAKE CLASSIFICATION PROGRAM massachusetts department of environmental quality engineering DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL thomas c.· mcmahon, director COMPILATIONOF LAKES, PONDS, AND RESERVOIRS RELATIVETO THE MASSACHUSETTSLAKE CLASSIFICATIONPROGRAM Commonwealth of Massachusetts Division of Water Pollution Control Water Quality and Research Section Westborough, Massachusetts March 1976 Approved by: Alfred C. Holland Purchasing Agent Est.Cost per Copy:$2.91 TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE Massachusetts Lake Classification Program 4 Introduction 4 Objectives of Lake Program 4 Total Inventory of Lakes, Ponds, and Reservoirs in the 7 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Total Surface Area of Lakes, Ponds, and Reservoirs in the 8 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Commonwealth of Massachusetts Drainage Basins: Hoosic River Basin 9 Housatonic River Basin 11 Deerfield River Basin 15 Westfield River Basin 17 Farmington River Basin 20 Connecticut River Basin 23 Millers River Basin 26 Chicopee River Basin 30 French and Quinebaug River Basins 35 Nashua River Basin 40 Blackstone River Basin 45 Merrimack River Basin 50 Concord and Sudbury River Basins 53 Assabet River Basin 56 Shawsheen River Basin 59 Parker River Basin 61 Ipswich River Basin 63 North Coastal Drainage 66 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS(Continued) ITEM PAGE Boston Harbor 69 Mystic River Basin 71 Neponset River Basin 73 Weymouth River Basin 76 Charles River Basin 7B North River Basin 83 South Coastal Drainage 86 Cape Cod Drainage 90 -

The Genus Lysimachia in the New World

XI E> RAR.Y OF THE U N IVLRSITY Of ILLINOIS 570-5 ILL v. 24 cop-2 material is re- TV,* person charging this the UtagT*" IptsTb eTor its rlt/rn to withdrawn on or before the which it was below. latest Date stamped result act.on and may for disciplinary the University. M L161—O-1096 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/genuslysimachiai24rayj Illinois Biological Monographs VOLUME XXIV University of Illinois Press URBANA BOARD OF EDITORS Leland Shanor Harvey I. Fisher H. Orin Halvorson William R. Horsfall Aubrey B. Taylor CONTENTS No. 1 The Mammals of the Huachuca Mountains, Southeastern Arizona GOODPASTER DONALD F. HOFFMEISTER AND WOODROW W. No. 2 The Myology of the Whooping Crane, Grus americana C. GOODMAN HARVEY I. FISHER AND DONALD Nos. 3-4 The Genus Lysimachia in the New World JAMES DAVIS RAY, JR. 2 > P The Genus Lysimachia in the New World JAMES DAVIS RAY, JR. Illinois biological monographs: Volume xxiv, Nos. 3-4 THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS URBANA, 1956 m* ILLINOIS BIOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS is the general title for a series of mono- graphs in botany, entomology, zoology, and allied fields. Each issue is an independent publication. For the convenience of bibliographers and librarians, each year's output is called a volume. Each volume consists of approximately 450 pages, priced at four dollars. A volume may consist of two, three, or four individual monographs. Prices of individual numbers are indicated in the list of titles given below. -

Bridge Inventory

OFFICE OF BRIDGE DEVELOPMENT BRIDGE INVENTORY BRIDGE NO. 0207000 THE UNITED STATES NAVAL ACADEMY BRIDGE MARYLAND 450 OVER THE SEVERN RIVER ANNE ARUNDEL COUNTY 1996 BIENNIAL AWARD - EXCELLENCE IN HIGHWAY DESIGN - USDOT - FHWA MARYLAND SECTION - AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CIVIL ENGINEERS - OUTSTANDING CIVIL ENGINEERING ACHIEVEMENT 1995 NATIONAL STEEL BRIDGE ALLIANCE AWARD /AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF STEEL CONSTRUCTION - MEDIUM SPAN CATEGORY 1996 AMERICAN CONSULTING ENGINEERS COUNCIL AWARD PRESIDENTIAL DESIGN AWARD - FEDERAL DESIGN ACHIEVEMENT AWARD NATIONAL QUALITY INITIATIVE ACHIEVEMENT AWARD - 1997 NATIONAL FINALIST Maryland Department of Transportation CONSULTING ENGINEERS COUNCIL OF MARYLAND - AWARD OF MERIT STATE HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION REV. 7/99 NOTES AND DEHNITIONS mtmm DEnNmON FO« A BHDGE: ANY STRUCTUU (BIUDGC , lOX CULVERT, BATTERY OF PIPES) THAT HAS A LENGTH CREATES THAN 20 FEET MEASURfD ALONG THE CENTERUNE OF HIGHWAY. ACCMT Aipttah Coatmi Corrugcriml M^ol Pip* AC AJuminwm Gird«f DEFINTnON OF SINGLE SINGLE STRUCTURE: ANY BRIDGE WHICH CARRIES A SINGLE ROADWAY OR DUAL ROADWAY ON WHICH •A Bride Arrh AND DUAL STRUCTURES: THE MEDIAN AREA IS CLOSED, SHALL BE CONSIDERED A SINGLE BRIDGE. A LONCTTUDINAL JOINT (2" OR LESS) IN THE MEDIAN BARRIER, OR MEDIAN AREA K vOX Cunwrt DOCS NOT CONSTITUTE A LARGE ENOUGH OPENING TO IDENTIFY THE STRUCTURE AS DUAL BRIDGES. •G iox Gtrd«- DUAL STRUCTURES: ANY STRUCTURE NOT MEETING THE CRTTERIA FOR A SINGLE BRIDGE IS TO BE (C) Qo9*d Strvctur^ CONSIDERED A DUAL STRUCTURE AND SHALL BE CONSIDERED TWO BRIDGES. CA Coocrvto ATQI ca CoocFsto B#oin CHART DEFINITION: A CONTRACT HAS NOT BEEN ACCEPTED FOR MAINTENANCE AND PLACED IN THE INVENTORY SYSTEM WHEN C3G CM KJ ••• Box Gird*r INFORMATION FOR THE DESIGN LOAD, YEAR BUILT, TYPE AND SPAN, AND ROADWAY HAVE BEEN LEFT BLANK. -

River Basin 11 Kinderhook and Baahbish River Basins 15 Bousatonic

· MASSACHUSETTSSTREAM CLASSIFICATIONPROGRAM • I I l/ '--------' \ .. --~\ °'---." , ·\v _..,__' f . I ✓ ·-.., I : r-·~';,.{___... I ., !', "\_ PART i: INVENTORY OF RIVERS AND STREAMS massochusetts deportment of environmantal quality· engineering DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL themas c. memo hon, director mcssachusetts department of fisheries, wi:dlife and recreational vehicles D!VISION OF FISHERIES ANO WILDLIFE richard cronin, director MASSACHUSETTSSTREAM CLASSIFICATION PROGRAM PART I: INVENTORYOF RIVERS ANDSTREAMS By David B. Halliwell Assistant Aquatic Biologist Bureau of Wildlife Research and Management Massachusetts.Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Recreational Vehicles Westborough Warren A. Kimball Principal Sanitary Engineer Arthur J. Screpetis Aquatic Biologist Technical Services Branch Massachusetts Division of Water Pollution Control Department of Environmental Quality Engineering Westborough JULY 1982 ---Cover Selected Types of Drainage Patterns ·· Typified in Massachusetts , PUBLICATION:#13003-138-72-10-82-CR 2nd. Printing Approved by Joh..~ J, Manton, State Purchasing Agent • TABLEOF CONTENTS ITEM FOREWORD V ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi • ABSTRACT vii LIST OF TABLES viii LIST OF FIGURES ix I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. HIERARCHICALLISTING OF RIVERSAND STREAMS OF MASSACHUSETTS 11 Hudson Drainage Sy~tem' 11 Boosic River Basin 11 Kinderhook and Baahbish River Basins 15 Bousatonic. Drainage System 17 Bousatonic River Basin 17 Connecticut Drainage System 21 Farmington River Basin 21 Westfield River Basin -

Biological Analysis of Impairment Of

FINAL Watershed Report for Biological Impairment of the Lower Wicomico River Watershed in Wicomico and Somerset Counties, Maryland Biological Stressor Identification Analysis Results and Interpretation FINAL DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT 1800 Washington Boulevard, Suite 540 Baltimore, Maryland 21230-1718 Submitted to: Water Protection Division U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region III 1650 Arch Street Philadelphia, PA 19103-2029 March 2014 BSID Analysis Results Lower Wicomico River Watershed Document version: March 2014 FINAL Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. i List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. i List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................................... ii Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... iii 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Lower Wicomico River Watershed Characterization .................................... 2 2.1 Location ...............................................................................................................2 2.2 Land Use ..............................................................................................................4 -

New England District

NEW ENGLAND DISTRICT NEW ENGLAND DISTRICT The New England District comprises all of New England except western Vermont and small portions of Massachusetts and Connecticut along their western boundaries, and includes small portions of southeastern New York. These areas are all embraced in the drainage basins tributary to Long Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean east of the New York-Connecticut State line. The District also includes Fishers Island, NY. IMPROVEMENTS Navigation Page Flood Control Page 1. Andrews River, MA............................................... 1-3 33. Aroostook River, Fort Fairfield, ME ....................1-14 2. Aunt Lydia's Cove, Chatham, MA......................... 1-3 34. Blackstone River Basin, MA and RI ....................1-14 3. Belfast Harbor, ME................................................ 1-3 34A. West HillDam, MA..........................................1-14 4. Boston Harbor,MA................................................ 1-4 35. Charles River (Natural Valley 5. Bridgeport Harbor, CT........................................... 1-4 Storage Areas), MA.........................................1-15 6. Cape Cod Canal, MA............................................. 1-5 36. Connecticut River Basin, VT, 7. Cocheco River, NH................................................ 1-5 NH, MA and CT..............................................1-15 8. Connecticut River below Hartford, CT.................. 1-6 36A. Ball Mountain Lake, VT....................................1-16 9. Great Salt Pond, Block Island, RI .........................