Reception of Pascal in the History of Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typology of Programming Languages E Early Languages E

Typology of programming languages e Early Languages E Typology of programming languages Early Languages 1 / 71 The Tower of Babel Typology of programming languages Early Languages 2 / 71 Table of Contents 1 Fortran 2 ALGOL 3 COBOL 4 The second wave 5 The finale Typology of programming languages Early Languages 3 / 71 IBM Mathematical Formula Translator system Fortran I, 1954-1956, IBM 704, a team led by John Backus. Typology of programming languages Early Languages 4 / 71 IBM 704 (1956) Typology of programming languages Early Languages 5 / 71 IBM Mathematical Formula Translator system The main goal is user satisfaction (economical interest) rather than academic. Compiled language. a single data structure : arrays comments arithmetics expressions DO loops subprograms and functions I/O machine independence Typology of programming languages Early Languages 6 / 71 FORTRAN’s success Because: programmers productivity easy to learn by IBM the audience was mainly scientific simplifications (e.g., I/O) Typology of programming languages Early Languages 7 / 71 FORTRAN I C FIND THE MEAN OF N NUMBERS AND THE NUMBER OF C VALUES GREATER THAN IT DIMENSION A(99) REAL MEAN READ(1,5)N 5 FORMAT(I2) READ(1,10)(A(I),I=1,N) 10 FORMAT(6F10.5) SUM=0.0 DO 15 I=1,N 15 SUM=SUM+A(I) MEAN=SUM/FLOAT(N) NUMBER=0 DO 20 I=1,N IF (A(I) .LE. MEAN) GOTO 20 NUMBER=NUMBER+1 20 CONTINUE WRITE (2,25) MEAN,NUMBER 25 FORMAT(11H MEAN = ,F10.5,5X,21H NUMBER SUP = ,I5) STOP TypologyEND of programming languages Early Languages 8 / 71 Fortran on Cards Typology of programming languages Early Languages 9 / 71 Fortrans Typology of programming languages Early Languages 10 / 71 Table of Contents 1 Fortran 2 ALGOL 3 COBOL 4 The second wave 5 The finale Typology of programming languages Early Languages 11 / 71 ALGOL, Demon Star, Beta Persei, 26 Persei Typology of programming languages Early Languages 12 / 71 ALGOL 58 Originally, IAL, International Algebraic Language. -

Simula Mother Tongue for a Generation of Nordic Programmers

Simula! Mother Tongue! for a Generation of! Nordic Programmers! Yngve Sundblad HCI, CSC, KTH! ! KTH - CSC (School of Computer Science and Communication) Yngve Sundblad – Simula OctoberYngve 2010Sundblad! Inspired by Ole-Johan Dahl, 1931-2002, and Kristen Nygaard, 1926-2002" “From the cold waters of Norway comes Object-Oriented Programming” " (first line in Bertrand Meyer#s widely used text book Object Oriented Software Construction) ! ! KTH - CSC (School of Computer Science and Communication) Yngve Sundblad – Simula OctoberYngve 2010Sundblad! Simula concepts 1967" •# Class of similar Objects (in Simula declaration of CLASS with data and actions)! •# Objects created as Instances of a Class (in Simula NEW object of class)! •# Data attributes of a class (in Simula type declared as parameters or internal)! •# Method attributes are patterns of action (PROCEDURE)! •# Message passing, calls of methods (in Simula dot-notation)! •# Subclasses that inherit from superclasses! •# Polymorphism with several subclasses to a superclass! •# Co-routines (in Simula Detach – Resume)! •# Encapsulation of data supporting abstractions! ! KTH - CSC (School of Computer Science and Communication) Yngve Sundblad – Simula OctoberYngve 2010Sundblad! Simula example BEGIN! REF(taxi) t;" CLASS taxi(n); INTEGER n;! BEGIN ! INTEGER pax;" PROCEDURE book;" IF pax<n THEN pax:=pax+1;! pax:=n;" END of taxi;! t:-NEW taxi(5);" t.book; t.book;" print(t.pax)" END! Output: 7 ! ! KTH - CSC (School of Computer Science and Communication) Yngve Sundblad – Simula OctoberYngve 2010Sundblad! -

Internet Engineering Jan Nikodem, Ph.D. Software Engineering

Internet Engineering Jan Nikodem, Ph.D. Software Engineering Theengineering paradigm Software Engineering Lecture 3 The term "software crisis" was coined at the first NATO Software Engineering Conference in 1968 by: Friedrich. L. Bauer Nationality;German, mathematician, theoretical physicist, Technical University of Munich Friedrich L. Bauer 1924 3/24 The term "software crisis" was coined at the first NATO Software Engineering Conference in 1968 by: Peter Naur Nationality;Dutch, astronomer, Regnecentralen, Niels Bohr Institute, Technical University of Denmark, University of Copenhagen. Peter Naur 1928 4/24 Whatshouldbe ourresponse to software crisis which provided with too little quality, too late deliver and over budget? Nationality;Dutch, astronomer, Regnecentralen, Niels Bohr Institute, Technical University of Denmark, University of Copenhagen. Peter Naur 1928 5/24 Software should following an engineering paradigm NATO conference in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, 1968 Peter Naur 1928 6/24 The hope is that the progress in hardware will cure all software ills. The Oberon System User Guide and Programmer's Manual. ACM Press Nationality;Swiss, electrical engineer, computer scientist ETH Zürich, IBM Zürich Research Laboratory, Institute for Media Communications Martin Reiser 7/24 However, a critical observer may notethat software manages to outgrow hardware in size and sluggishness. The Oberon System User Guide and Programmer's Manual. ACM Press Nationality;Swiss, electrical engineer, computer scientist ETH Zürich, IBM Zürich Research Laboratory, Institute for Media Communications Martin Reiser 8/24 Wirth's computing adage Software is getting slower more rapidly than hardware becomes faster. Nationality;Swiss, electronic engineer, computer scientist ETH Zürich, University of California, Berkeley, Stanford University University of Zurich. Xerox PARC. -

Oral History Interview with John Brackett and Doug Ross

An Interview with JOHN BRACKETT AND DOUG ROSS OH 392 Conducted by Mike Mahoney on 7 May 2004 Needham, Massachusetts Charles Babbage Institute Center for the History of Information Processing University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Copyright, Charles Babbage Institute John Brackett and Doug Ross Interview 7 May 2004 Oral History 392 Abstract Doug Ross and John Brackett focus on the background of SofTech and then its entry into the microcomputer software marketplace. They describe their original contact with the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) and licensing the p-System which had been developed there. They discuss the effort required to bring the program to production status and the difficulties in marketing it to the sets of customers. They talk about the transition from 8 bit to 16 bit machines and how that affected their market opportunities. They conclude with a review of the negotiations with IBM and their failure to get p-System to become a primary operating environment. That, and the high performance of Lotus 1-2-3, brought about the demise of the p- System. [John Brackett requested that the following information from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, be provided as an introduction to this oral history interview: “UCSD p-System or UCSD Pascal System was a portable, highly machine independent operating system based upon UCSD Pascal. The University of California, San Diego Institute for Information Systems developed it in 1978 to provide students with a common operating system that could run on any of the then available microcomputers as well as campus DEC PDP-11 minicomputers. UCSD p- System was one of three operating systems (along with PC-DOS and CP/M-86) that IBM offered for its original IBM PC. -

Type Extensions, Wirth 1988

Type Extensions N. WIRTH lnstitut fijr Informatik, ETH, Zurich Software systems represent a hierarchy of modules. Client modules contain sets of procedures that extend the capabilities of imported modules. This concept of extension is here applied to data types. Extended types are related to their ancestor in terms of a hierarchy. Variables of an extended type are compatible with variables of the ancestor type. This scheme is expressed by three language constructs only: the declaration of extended record types, the type test, and the type guard. The facility of extended types, which closely resembles the class concept, is defined in rigorous and concise terms, and an efficient implementation is presented. Categories and Subject Descriptors: D.3.3 [Programming Languages]: Language Constructs-data types and structures; modules, packuges; D.3.4 [Programming Languages]: Processors-code generation General Terms: Languages Additional Key Words and Phrases: Extensible data type, Modula-2 1. INTRODUCTION Modern software development tools are designed for the construction of exten- sible systems. Extensibility is the cornerstone for system development, for it allows us to build new systems on the basis of existing ones and to avoid starting each new endeavor from scratch. In fact, programming is extending a given system. The traditional facility that mirrors this concept is the module-also called package-which is a collection of data definitions and procedures that can be linked to other modules by an appropriate linker or loader. Modern large systems consist, without exception, of entire hierarchies of such modules. This notion has been adopted successfully by modern programming languages, such as Mesa [4], Modula-2 [8], and Ada [5], with the crucial property that consistency of interfaces be verified upon compilation of the source text instead of by the linking process. -

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

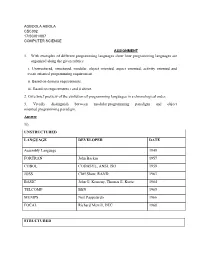

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

Pioneers of Computing

Pioneers of Computing В 1980 IEEE Computer Society учредило Золотую медаль (бронзовую) «Вычислительный Пионер» Пионерами учредителями стали 32 члена IEEE Computer Society, связанных с работами по информатике и вычислительным наукам. 1 Pioneers of Computing 1.Howard H. Aiken (Havard Mark I) 2.John V. Atanasoff 3.Charles Babbage (Analytical Engine) 4.John Backus 5.Gordon Bell (Digital) 6.Vannevar Bush 7.Edsger W. Dijkstra 8.John Presper Eckert 9.Douglas C. Engelbart 10.Andrei P. Ershov (theroretical programming) 11.Tommy Flowers (Colossus engineer) 12.Robert W. Floyd 13.Kurt Gödel 14.William R. Hewlett 15.Herman Hollerith 16.Grace M. Hopper 17.Tom Kilburn (Manchester) 2 Pioneers of Computing 1. Donald E. Knuth (TeX) 2. Sergei A. Lebedev 3. Augusta Ada Lovelace 4. Aleksey A.Lyapunov 5. Benoit Mandelbrot 6. John W. Mauchly 7. David Packard 8. Blaise Pascal 9. P. Georg and Edvard Scheutz (Difference Engine, Sweden) 10. C. E. Shannon (information theory) 11. George R. Stibitz 12. Alan M. Turing (Colossus and code-breaking) 13. John von Neumann 14. Maurice V. Wilkes (EDSAC) 15. J.H. Wilkinson (numerical analysis) 16. Freddie C. Williams 17. Niklaus Wirth 18. Stephen Wolfram (Mathematica) 19. Konrad Zuse 3 Pioneers of Computing - 2 Howard H. Aiken (Havard Mark I) – США Создатель первой ЭВМ – 1943 г. Gene M. Amdahl (IBM360 computer architecture, including pipelining, instruction look-ahead, and cache memory) – США (1964 г.) Идеология майнфреймов – система массовой обработки данных John W. Backus (Fortran) – первый язык высокого уровня – 1956 г. 4 Pioneers of Computing - 3 Robert S. Barton For his outstanding contributions in basing the design of computing systems on the hierarchical nature of programs and their data. -

IBM Highlights, 1985-1989 (PDF, 145KB)

IBM HIGHLIGHTS, 1985 -1989 Year Page(s) 1985 2 - 7 1986 7 - 13 1987 13 - 18 1988 18 - 24 1989 24 - 30 February 2003 1406HC02 2 1985 Business Performance IBM’s gross income is $50.05 billion, up nine percent from 1984, and its net earnings are $6.55 billion, up 20 percent from the year before. There are 405,535 employees and 798,152 stockholders at year-end. Organization IBM President John F. Akers succeeds John R. Opel as chief executive officer, effective February 1. Mr. Akers also is to head the Corporate Management Board and serve as chairman of its Policy Committee and Business Operations Committee. PC dealer sales, support and operations are transferred from the Entry Systems Division (ESD) to the National Distribution Division, while the marketing function for IBM’s Personal Computer continues to be an ESD responsibility. IBM announces in September a reorganization of its U.S. marketing operations. Under the realignment, to take effect on Jan. 1, 1986, the National Accounts Division, which markets IBM products to the company’s largest customers, and the National Marketing Division, which serves primarily medium-sized and small customer accounts, are reorganized into two geographic marketing divisions: The North-Central Marketing Division and the South-West Marketing Division. The National Distribution Division, which directs IBM’s marketing efforts through Product Centers, value-added remarketers, and authorized dealers, is to merge its distribution channels, personal computer dealer operations and systems supplies field sales forces into a single sales organization. The National Service Division is to realign its field service operations to be symmetrical with the new marketing organizations. -

50 Years of Pascal Niklaus Wirth the Programming Language Pascal Has Won World-Wide Recognition

50 Years of Pascal Niklaus Wirth The programming language Pascal has won world-wide recognition. In celebration of its 50th birthday I shall remark briefly today about its origin, spread, and further development. Background In the early 1960's, the languages Fortran (John Backus, IBM) for scientific, and Cobol (Jean Sammet, IBM and DoD) for commercial applications dominated. Programs were written on paper, then punched on cards, and one waited for a day for the results. Programming languages were recognized as essential aids and accelerators of the hard process of programming. In 1960, an international committee published the language Algol 60. It was the first time that a language was defined by concisely formulated constructs and by a precise, formal syntax. Already two years later it was recognized that a few corrections and improvements were needed. Mainly, however, the range of applications should be widened, because Algol 60 was intended for scientific calculations (numerical mathematics) only. Under the auspices of IFIP a Working Group (WG 2.1) was established to tackle this project. The group consisted of about 40 members with almost the same number of opinions and views about what a successor of Algol should look like. There ensued many discussions, and on occasions the debates ended even violently. Early in 1964 I became a member, and soon was requested to prepare a concrete proposal. Two factions had developed in the committee. One of them aimed at a second, after Algol 60, milestone, a language with radically new, untested concepts and pervasive flexibility. The other faction remained more modest and focused on realistic improvements of known concepts. -

*Programing Languages 4Tching Techniques

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 134 150 IR 004 309 AUTHOR Worland, Peter B. TITLE Teaching Structured Fortran without Structured Extensions. INSTITUTION Gustavus Adolphus Coll., St. Peter, Minn. PUB DATE 76 Wen 25p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$1.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Algorithms; College Pr3grams; *Programing; *Programing Languages 4Tching Techniques IDENTIFIERS *FORTRAN ABSTRACT Six control structures are used in teaching a college Fortran programing course: (1) simple sequences of instruction without any control statement,(2) IF-THEN selection, (3) IF-THEN-ELSE selection,(4) definite loop, (5) indefinite loop, and (6) generalized IF-THEN-ELSE case structure. Outlines, instead of flowcharts, are employed for algorithm development. Comparisons of student performance in structured and standard Fortran classes show no statistical significance, but suggest that the former approach is appropriate. (SC) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy a-vailable. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hatdcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. * *********************************************************************** -r TEACHING STRUCTURED FORTRAN WITHOUT STRUCTURED EXTENSIONS by PETER B. WORLAND GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS COLLEGE ST. PETER, MINNESOTA56082 TC -P RIGHTED MA'EFII,. THIS COPY. PEEN c,RANTED BY --Peter B._ WoT;a0. TO ERIC AND OR,T.AT.i:AY;0,4s OPERATING UNDER AGREEMENTL Ft THE NATIONAL IN STITUTE OF EDuCATIOTi FURTHER RERRO- DUCTION OUTSIDE EPIC SYSTEM RE- QUIRES PERMISW.N !RE COPYRIGHT' OWNER U.S. -

Software Engineering

Software Engineering A historical perspective and a current assessment Niklaus Wirth Zurich, 22.11.2010 Early days 1960: Language and compiler Neliac Overriding property: A mess Extending language, fixing compiler bugs: Black art Missing a scientific basis Therefore a unique subject for scientific research The ESSENCE of SE: Cleaning the mess How can you write “correct” programs, if there is no rigorous specification of your notation? Algol 60 appeared as an excellent starting point It provided structure, defined in a rigorous mathematical sense: Syntax Giving a strong impetus to methods of syntactic analysis EBNF: The Syntax of Syntax • syntax = {rule}. • rule = ident “:=“ expression “.” . • expression = term {“|” term}. • term = factor {factor}. • factor = ident | string | “(“expression”)” | • “[“expression”]” | “{“expression”}”. Semantics Syntax ok, but what about meaning? The dominant idea: Operational semantics Attach a meaning to each syntactic construct Semantic of each construct defined in terms of a short program, specified in a simpler language Garwick, Wirth: Euler Did not solve the problem, simply moved it down to a lower plane Axiomatic definition • R. Floyd (1968) • C.A.R.Hoare (1969) - Assertion • E.W. Dijkstra (1973) - Predicate transformer • Axiomatic defintion of the PL Pascal (1973) • Programming = Constructing correctness proof • The ESSENCE of SE: Not ceaning up, but avoiding the mess (Dijkstra) State of the Art (2010) • Correctness proofs are rarely used. Why? • The proof is more complex than the program • The theory requires a strong ability for formula manipulation. Most prog. lack it. • Programming methodology has improved: - Structures, modularity, type checking, and languages supporting them. - Interactive tools to help locating errors Consequences • Industrial SE has produced a myriad of tools, emerging from early “symbolic debuggers” • Resulting work mode: Try, test, fix. -

Wirth Abstract an Entire Potpourri of Ideas Is Listed from the Past Decades of Computer Science and Computer Technology

1 Zürich, 2. 2. 2005 / 15. 6. 2005 Good Ideas, Through the Looking Glass Niklaus Wirth Abstract An entire potpourri of ideas is listed from the past decades of Computer Science and Computer Technology. Widely acclaimed at their time, many have lost in splendor and brilliance under today’s critical scrutiny. We try to find reasons. Some of the ideas are almost forgotten. But we believe that they are worth recalling, not the least because one must try to learn from the past, be it for the sake of progress, intellectual stimulation, or fun. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Hardware Technology 3. Computer Architecture 3.1. Representation of numbers 3.2. Data addressing 3.3. Expression Stacks 3.4. Variable length data 3.5. Storing return addresses in the code 3.6. Virtual Addressing 3.7. Memory protection and user classes 3.8. Complex Instruction Sets 3.9. Register windows 4. Programming Language Features 4.1. Notation and Syntax 4.2. The GO TO statement 4.3. Switches 4.4. Algol’s complicated for statement 4.5. Own variables 4.6. Algol’s name parameter 4.7. Incomplete parameter specifications 4.8. Loopholes 5. Miscellaneus techniques 5.1. Syntax analysis 5.2. Extensible languages 5.3. Nested procedures and Dijkstra’s display 5.4. Tree-structured symbol tables 5.5. Using wrong tools 5.6. Wizards 6. Programming paradigms 6.1. Functional programming 6.2. Logic programming 2 6.3. Object-oriented programming 7. Concluding remarks 1. Introduction The history of Computing has been driven by many good and original ideas.