MONTAUK MAX FRISCH Translated by Geoffrey Skelton Introduction by Jonathan Dee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Recherchierte Dokumente

Herr der Bücher: Marcel Reich-Ranicki in seiner Frankfurter Wohnung MONIKA ZUCHT / DER SPIEGEL SPIEGEL-GESPRÄCH „Literatur muss Spaß machen“ Marcel Reich-Ranicki über einen neuen Kanon lesenswerter deutschsprachiger Werke SPIEGEL: Herr Reich-Ranicki, Sie haben für die an der Literatur interessiert sind. Gibt es um die Schule geht, für den Unterricht den SPIEGEL Ihren persönlichen literari- es überhaupt einen Bedarf für eine solche besonders geeigneter Werke. Die Frage, ob schen Kanon zusammengestellt, die Sum- Liste literarischer Pflichtlektüre? wir einen solchen Katalog benöti- me Ihrer Erfahrung als Literaturkritiker – Reich-Ranicki: Ein Kanon ist nicht etwa ein gen, ist mir unverständlich, denn für Schüler, Studenten, Lehrer und dar- Gesetzbuch, sondern eine Liste empfehlens- über hinaus für alle, werter, wichtiger, exemplarischer und, wenn Das Gespräch führte Redakteur Volker Hage. Chronik der deutschen Literatur Marcel Reich-Ranickis Kanon Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Andreas Gryphius, 1749 –1832 1616 –1664 „Die Leiden des Gedichte jungen Werthers“, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, „Faust I“, „Aus Walther von der Christian Hofmann Johann Christian 1729 –1781 meinem Leben. Das Nibe- Vogelweide, Martin Luther, von Hofmannswaldau, Günther, „Minna von Barnhelm“, Dichtung und lungenlied ca. 1170 –1230 1483 –1546 1616 –1679 1695 –1723 „Hamburgische Dramaturgie“, Wahrheit“, (um 1200) Gedichte Bibelübersetzung Gedichte Gedichte „Nathan der Weise“ Gedichte MITTELALTER16. JAHRHUNDERT 17. JAHRHUNDERT 18. JAHRHUNDERT 212 der spiegel 25/2001 Titel der Verzicht auf einen Kanon würde den der verfassten Rahmenrichtlinien und und auch die liebe Elke Heidenreich. Be- Rückfall in die Barbarei bedeuten. Ein Lehrpläne für den Deutschunterricht an merkenswert der Lehrplan des Sächsischen Streit darüber, wie der Kanon aussehen den Gymnasien haben einen generellen Staatsministeriums für Kultus: Da werden sollte, kann dagegen sehr nützlich sein. -

Title:'I Have No Language for My Reality': the Ineffable As Tension in the 'Tale' of Bluebeard Author(S): Marga I. Weigel Public

Page 1 of 7 Title:'I Have No Language for My Reality': The Ineffable as Tension in the 'Tale' of Bluebeard Author(s): Marga I. Weigel Publication Details: World Literature Today 60.4 (Autumn 1986): p589-592. Source:Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism. Ed. Janet Witalec. Vol. 121. Detroit: Gale, 2002. From Literature Resource Center. Document Type:Critical essay Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale, COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale, Cengage Learning Full Text: [(essay date autumn 1986) In the following essay, Weigel explores the role of communication and speech in Bluebeard.] Following acquittal on charges of murdering a prostitute, Felix Theodor Schaad, M.D., begins to search for the reasons why his life has been a failure. The public cross-examination in the courtroom is followed by Schaad's private cross-examination, an attempt to determine his guilt which ultimately drives him to confess the murder and shortly thereafter to attempt suicide. In the last analysis he is indeed convinced that he is guilty, although he has consistently maintained, both to the court and afterward to himself, that he did not commit the murder.1 It may be of interest and perhaps not unimportant for Frisch's literary development that a variant of this "tale" appeared in the novel Gantenbein (1964), almost twenty years earlier. A "personality, a cultured man"2 is brought before the court and accused of the murder of his former lover Camilla, a prostitute. Far more than the sum of the evidence against him, it is his behavior which makes him suspect: "He can't find the words in which to express complete innocence" (262). -

Hermann Kurzke Die Kürzeste Geschichte Der Deutschen Literatur Und Andere Essays

Unverkäufliche Leseprobe Hermann Kurzke Die kürzeste Geschichte der deutschen Literatur und andere Essays 256 Seiten, Paperback ISBN: 978-3-406-59989-7 © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München 1. Abteilung Kurzkes Kanon Eine Bibliothek der Verdrängung Thomas Mann, «Doktor Faustus» In meinem Elternhaus wurde viel gelesen, aber nur Zweit- und Dritt- klassiges. Mein Vater war Physiker und hatte bei Kriegsende Grund, den Amerikanern dankbar zu sein. So kam es, daß unsere Bücher- schränke angefüllt waren mit englisch-amerikanischer Literatur – das meiste namenlos, serienweise Kriminalromane und Reader’s Digest- Auswahlbücher, nur weniges noch heute bekannt. Da stand Margaret Mitchell (natürlich «Vom Winde verweht») neben John Steinbeck («Jenseits von Eden»), Cecil S. Forester war mit seinen Hornblower- Romanen vertreten und Thomas Wolfe mit «Schau heimwärts, En- gel». Besonders gute Chancen, gekauft zu werden, hatten Autoren mit christlichem Hintergrund, Thornton Wilder und Bruce Marshall, C. S. Lewis und auch noch William Faulkner («Licht im August») – allein zu Lieblingen wurden sie nicht, obgleich meine Eltern jedes Buch, das sie gekauft hatten, pfl ichttreu zu Ende lasen. Aber die wah- ren Favoriten las man damals nicht nur einmal, sondern mehrfach, die Qualität war erst erwiesen, wenn der Band schiefgelesen war. Ernest Hemingway fehlte; er war Nihilist und Selbstmörder, hatte sich im 11 Spanischen Bürgerkrieg auf die Seite der Kommunisten geschlagen und galt auch sittlich als nicht korrekt. Was fehlte sonst? Natürlich die Linke, Bertolt Brecht und Anna Seghers und überhaupt das deut- sche Exil, das unter einem unbestimmten Generalverdacht stand, vermutlich dem der Vaterlandslosigkeit. Von Thomas Mann gab es lediglich die «Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull», die als un- terhaltsam galten. -

«Viele Anspielungen Gehen Ohnehin Verloren» Autofiktion Und Intertextualität in Max Frischs Montauk

Hanspeter Affolter «Viele Anspielungen gehen ohnehin verloren» Autofiktion und Intertextualität in Max Frischs Montauk Hanspeter Affolter »Viele Anspielungen gehen ohnehin verloren« Autofiktion und Intertextualität in Max Frischs Montauk DiePubliziert Druckvorstufe mit Unterstützung dieser Publikation des Schweizerischen wurde vom Nationalfonds Schweizerischen zur NationalfondsFörderung der wissenschaftlichenzur Förderung der Forschung. wissenschaftlichen Forschung unterstützt. Informationen zum Verlagsprogramm: www.chronos-verlag.ch Umschlagbild: Die Abbildung auf dem Titelblatt zeigt ein Selbstporträt Max Frischs, das er während der in Montauk beschriebenen USA-Reise für den amerikanischen Sammler Burt Britton gezeichnet hat (Burt Britton [Hg.], Self-portrait. Book People Picture Themselves, New York: Random House, 1976, S. 202). © 2019 Chronos Verlag, Zürich Print: ISBN 978-3-0340-1499-1 E-Book (PDF): DOI 10.33057/chronos.1499 Für Katrin, Emilia und Milena 7 Inhalt Dank 9 1 Einleitung 13 1.1 Zwischen Faktualität und Fiktionalität 13 1.2 Rezeption 23 1.3 Autofiktion 32 2 My Life as a Man und Leerstellen in den Erinnerungen an Ingeborg Bachmann 49 2.1 Uwe Johnson als Lektor von Montauk 49 2.2 »Was verschweigt es und warum?« 60 2.3 Philip Roths My Life as a Man als Intertext 67 3 Undine geht und die Offenlegung autobiografischer Motive 73 3.1 Lynn als Undine 73 3.2 Biografische Motive 82 4 Simultan als Kontrastfolie für Max’ und Lynns gemeinsames Wochenende 99 4.1 Jäger, Autofahrer und Eroberer 99 4.2 Eine Frage des Alters 111 5 Departures -

Max Frisch: Montauk Literaturklub Sindelfingen Am 18. Juni 2012

Max Frisch: Montauk Literaturklub Sindelfingen am 18. Juni 2012 1 Ein aufrichtiges Buch? Max Frisch ist am 15. Mai 1911 geboren und am 4. April 1991 im Alter von knapp 80 Jahren gestorben. Er hat „Montauk“ 1975, also mit 64, geschrieben. Darin geht es um ein Wochenende auf Long Island bei New York, ein Jahr zuvor, am 11.5.1974 (9)1 und 12.5.1974 (137). Am 14.5. fliegt er nach Europa (96). „Mon- tauk“ ist eine Erzählung, die an manchen Stellen wie ein Tagebuch wirkt: T 1 Ich habe mir mein Leben verschwiegen. Ich habe irgendeine Öffentlichkeit be- dient mit Geschichten. Ich habe mich in diesen Geschichten entblößt, ich weiß, bis zur Unkenntlichkeit. Ich lebe nicht mit der eigenen Geschichte, nur mit Teilen davon, die ich habe literarisieren können. […] Ich habe mich selbst nie beschrieben. Ich habe mich nur verraten. (156) Acht Sätze, die mit „ich“ beginnen. Sie handeln vom Verschweigen durch Schrei- ben, vom Verbergen durch Entblößen. Bisher habe er sich versteckt in seinen Veröffentlichungen, sich gespiegelt in Romanfiguren wie Gantenbein, Stiller und Faber. In „Montauk“ soll es anders sein. Wir sollen denken, die darin gegenwärti- ge Ich-Figur sei der wirkliche Schriftsteller Max Frisch. Manches spricht dafür: Er wird im Buch mit Max angeredet (52) oder sogar mit vollem Namen: Stimmt es, Herr Frisch, daß sie die Frauen hassen? (67) Aber die andere Hauptperson, Lynn, hat in der Realität den Namen Alice Locke-Carey. T 2 Liste wichtiger Frauen in Frischs Leben: 1934 – 1938: Käte Rubinson 1941 – 1959: Gertrude Anna Constanze von Meyenburg -

Graf Öderland ~ Ebook Graf Öderland Harcourt, Brace & World - Groupon® Official Site

- < Graf Öderland ~ eBook Graf Öderland Harcourt, Brace & World - Groupon® Official Site Description: - -Graf Öderland - Edition Suhrkamp in American text editionsGraf Öderland Notes: 1 This edition was published in 1966 Filesize: 25.62 MB Tags: #Max #Frisch Frisch, Max (Rudolf) There were numerous short sketches and essays along with three novels or longer narratives, 1934 , it's belated sequel I adore that which burns me 1944 and the narrative Antwort aus der Stille 1937. The way actor Maja Beckmann develops this, the way Leonie Böhm arranges it in images, the way Johannes Rieder reflects it in music — is breath-taking and intelligent. Groupon® Official Site It finally became possible, some months after Frisch's death, for a full-scale cinema version of Homo Faber to be produced. Again, the three later prose works Montauk 1975 , Der Mensch erscheint im Holozän 1979 , and Blaubart 1981 , are frequently grouped together by scholars. Andorra: Stück in zwölf Bildern produced Zurich, 1961. When the War Was Over Apart from a few early works, most of Frisch's books and plays have been translated into around ten languages, while the most translated of all, Homo Faber, has been translated into twenty-five languages. Frisch's social criticism was particularly sharp in respect of. Das Absurde ist da: „Graf Öderland“, neu inszeniert Frisch's early novels Stiller 1954; I'm Not Stiller , Homo Faber 1957 , and Mein Name sei Gantenbein 1964; A Wilderness of Mirrors portray aspects of modern intellectual life and examine the theme of identity. Mobilität und Migration The piece was first unveiled as a radio play in April 1979, receiving its stage premier in six months later. -

The Scofield

THE SCO FIELD O MAX FRISCH IDENTITY ISSUE 1.4 SPRING 2016 THE SCOFIELD IAN FRANCIS THE SCO FIELD 1.4 “So it is not because I feel a duty to teach or convert the public that I publish my things but because, if one is to recognize one’s own identity, one needs imaginary readers.” MAX FRISCH, MONTAUK Interview Disaster “Here Frisch for the first time elaborated on one of his dominant themes, by some critics the central theme of his oeuvre: the search for identity as the questioning of the existence of a self-contained character or personality, its dependence on the reciprocity of interpersonal image-making, and the impossibility of escaping from the roles we assign to each other.” GERHARD F. PROBST, INTRODUCTION TO PERSPECTIVES ON MAX FRISCH “I know my literary trademark is the problem of identity, MAX FRISCH IDENTITY even though I do not identify with this trademark myself. But both my trademark and I are fine with this.” MAX FRISCH IN AN INTERVIEW WITH DIETER E. ZIMMER FROM DIE ZEIT ISSUE 1.4 SPRING 2016 PAGE 2 THE SCOFIELD TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Scofield Thayer 2 Markers of Silence and Contemplation: A 28 Sculpture by Gaston Lachaise Conversation in Three Parts with Tony Perez, Jakob Vala, and Jonathan Dee Interview Disaster 2 Interview by Conor Higgins Painting by Ian Francis And Dreaming 32 Table of Contents 3 Painting by Jennifer Packer “That Brought Him to That Creaking Room 33 Always a Question 8 Was Age”: Max Frisch’s Man in the Holocene Letter from the Editor by Tyler Malone Essay by Sven Birkerts Who Is That? 12 Ghost Chamber with the Tall Door (New 39 Photograph by Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr. -

Ss Montauk.Pdf

Nutzungshinweis: Es ist erlaubt, dieses Dokument zu drucken und aus diesem Dokument zu zitieren. Wenn Sie aus diesem Dokument zitieren, machen Sie bitte vollständige Angaben zur Quelle (Name des Autors, Titel des Beitrags und Internet-Adresse). Jede weitere Verwendung dieses Dokuments bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Genehmigung des Autors. Quelle: http://www.mythos-magazin.de ‚Montauk’: Von Max Frischs Roman zu Leonhard Koppelmanns Radio-Hörspiel Masterarbeit im Fach Germanistik zur Erlangung des Grades Master of Arts (M.A.) der Philosophischen Fakultät der Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf von Saskia Schwedler Prüfer Apl. Professor Dr. Peter Tepe "Was ist ein Hörspiel?" "Das gleiche wie ein Stummfilm, nur umgekehrt." "Aah!" "Und wer schaut sich des an?" "Niemand, man hört es - Hör-Spiel!" "Aah!"1 1 Stan und Ollie im Gespräch mit einem Hörspielautor im Theaterstück "Stan und Ollie in Deutschland" von Urs Widmer Inhalt 1. Einleitung ........................................................................................................ 1 2. Montauk – Max Frisch ................................................................................... 3 2.1 Vorgehensweise .......................................................................................... 3 2.2 Deskriptiver Teil – Basis-Analyse .............................................................. 5 2.2.1 Kurzdarstellung von ‚Montauk‘ ............................................................................ 5 2.2.2 Textkonstruktion .................................................................................................. -

Geologic Narration in German Fiction Since 1945 a DISSERTATION

Telling Deep Time: Geologic Narration in German Fiction since 1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Kiley M Kost IN PARTIAL FULFULLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Charlotte Melin April 2019 © Kiley M Kost 2019 Acknowledgements This dissertation was made possible through the support and guidance from many important people, for whom I am incredibly grateful. Above all, my advisor Professor Charlotte Melin has played an essential role from well before this project began (let’s call it the deep past). From encouraging me to apply for graduate school, creating engaging seminars that helped me deepen my understanding of literature, providing copious amounts (copious!) of very useful feedback on my work, advising me in applications for conference and fellowships, encouraging breaks for walks and chocolate to always pushing me “through the muck” to just write, I could not have done this without her. I am also grateful to the members of my dissertation committee. Matthias Rothe’s support during graduate school has meant a tremendous amount to me. Rüdiger Singer helped me broaden my focus and make connections with different historical eras. Daniel Philippon played a large role in shaping my project and paving a path for me to believe in my work. He was also instrumental in supporting my applications to a number of fellowships and grants. I am deeply grateful for the time I spent at the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society in Munich with the support of a Fulbright research grant in 2017-2018. -

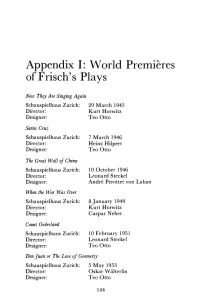

Appendix 1: World Premieres of Frisch's Plays

Appendix 1: World Premieres of Frisch's Plays Now They Are Singing Again Schauspielhaus Zurich: 29 March 1945 Director: Kurt Horwitz Designer: Teo Otto Santa Cru;:; Schauspielhaus Zurich: 7 March 1946 Director: Heinz Hilpert Designer: Teo Otto The Great Wall of China Schauspielhaus Zurich: I 0 October 1946 Director: Leonard Steckel Designer: Andre Perottet von Laban When the War Was Over Schauspielhaus Zurich: 8January 1949 Director: Kurt Horwitz Designer: Caspar Neher Count Oederland Schauspielhaus Zurich: 10 February 1951 Director: Leonard Steckel Designer: Teo Otto Don juan or The Love of Geometry Schauspielhaus Zurich: 5 May 1953 Director: Oskar Wiilterlin Designer: Teo Otto 144 Appendix I 145 The Fire Raisers Schauspie1haus Zurich: 29 March 1958 Director: Oskar Wiilterlin Designer: Max Frisch Andorra Schauspielhaus Zurich: 2, 3, 4 November 1961 Director: Kurt Hirschfeld Designer: Teo Otto Biography. A Game Schauspielhaus Zurich: 1, 2, 3 February 1968 Director: Leopold Lindtberg Designer: Teo Otto Triptych. Three Scenic Panels Centre dramatique de Lausanne: 10 October 1979 Director: Michel Soutter Designer: Jean Lecoultre (German premiere: Akademietheater Vienna: 1 February 1981 Director: Erwin Axer Designer: Ewa Starowieyska) Appendix II: Chronological Table 1911 Born 15 May in Zurich. Father: Franz Bruno Frisch (Architect), Mother: Karolina Bettina (nee Wilder muth). 1924-30 Realgymnasium, Zurich. 1931 Matriculates at Zurich University to read German. 1932 Father dies. Leaves university to work as freelance journalist. 1933 Travels abroad for first time: Prague, Budapest, Belgrade, Istanbul, Athens, Rome. 1934 Jiirg Reinhart. Eine sommerliche Schicksalsfahrt (novel). 1935 First visit to Germany. 1936-41 Reads Architecture at the Eidgenossische Technische Hochschule, Zurich. 1937 Antwort aus der Stille. -

Max Frischの „Montauk“ について

Max Frischの„Montauk"について 【論 文】 Max Frischの „Montauk“ について 村 上 文 彦 要 旨 スイスを代表する作家Max Frischはその著書 „Montauk“ の中で交流のあった人達を描 き出した。とりわけ女性たちとの関わりは多彩であった。彼はこの作品を「正直な本」で あると前置きしているが,疑義を唱える声もあり,自伝か物語かその判断は分かれる。ま た彼は大胆な自己暴露と同時にいくつかの事実は伏せている。生前彼が設定した資料非公 開の時期も過ぎ,新たな事実も明らかになってきだしたが,どのような人たちが彼の人生 を彩ったのであろうか。 はじめに 1991年にMax Frisch(1911−1991)がそのほぼ80歳の生涯を終え,それから今日まで さらに23年の年月が経過し,時は足早に流れていった。スイスで最も高名であったこの作 家Max Frischを偲んでチューリヒ市は1998年にMax-Frisch-Preisという賞を設けた。この 賞は,芸術的に妥協しない形で民主的社会の根本問題を扱ってすぐれた作品を執筆した作 家に与えられるもので,4年ごとに受賞者が決められ,これまで5人の受賞者を出し,そ れぞれ50,000フランという高額の賞金が授与されていることからもMax Frischの大きさと チューリヒ市の力の入れ具合が窺がえるのである。1 このような賞が設けられ,複数の受賞者を出し,さらにその中で2002年第2回受賞者の Jörg Steinerが既に他界してしまったことを思えば,Max Frischは遠い過去の人になって しまった印象も受けるが,彼に関わった様々な人たちがいまだ多数健在で,Frischの思い 出を胸に生きているのである。Frischは63歳の時に „Montauk“ という作品の中でそれま での自分の過去をふり返り,とりわけ心に残った懐かしい人々を描いている。彼はどのよ うな人たちと交流を交わし,どのような人生をたどったのか,そしてどのように作品に反 映させたのかを辿ってみたい。 — 1 — 総合文化研究第20巻第2号(2014.12) Max Frischの„Montauk"について 1. „Montauk“ の成立 „Montauk“ とは当時63歳のMax Frischが1974年から75年にかけて執筆した散文作品 である。大部分は1974年夏,版画家にして画家でもあり彫刻家でもある友人Gottfried Honegger(1917年−)のチューリヒ郊外,チューリヒ動物園の近くにあるゴックハウゼ ン地区にあるアトリエで執筆した。この作品を執筆する動機はアメリカ旅行にあった。 そもそもFrischは1951年,40歳の時にアメリカのロックフェラー財団から奨学金を給付 され約1年1か月アメリカに滞在したが,その時ニューヨークを初めとてして様々な都市 を訪問し,メキシコまでも足を伸ばし,アメリカから様々な刺激を受けた。そしてアメリ カに好印象を持った彼は,それ以後何度かのアメリカ滞在を行っている。そして1974年 4月,63歳になる直前のFrischは,アメリカ芸術文学アカデミー(Academy of Arts and Letters)と国立芸術文学研究所(National Institute of Arts and Letters)の名誉会員を 授与されるためアメリカに旅行した。この機会にアメリカの女性出版者Helen Wolff(1910 −1994)がFrischのために約1か月間の朗読ツアーを企画した。Frischはその申し出を受 けたのである。2このWolffはマケドニア生まれで,父親がドイツ人,母親がオーストリア -

Max Frisch – Ein Leben in Entwürfen Schaffens Stand Die Auseinandersetzung Mit Der Eigenen Identität, Vor Allem Auch Die Unmöglichkeit, Ihrer Selber Habhaft Zu Werden

Feldkircher Literaturtage 2016 – Max Frisch Sein Ringen Das Werk von Max Frisch zählt heute zum Kanon deutschsprachiger Literatur. Im Zentrum seines Max Frisch – Ein Leben in Entwürfen Schaffens stand die Auseinandersetzung mit der eigenen Identität, vor allem auch die Unmöglichkeit, ihrer selber habhaft zu werden. So notiert der Protagonist seines Romans Stiller (1954): „Man kann Vor 25 Jahren starb Max Frisch (1911-1991). Die Feldkircher Literaturtage 2016 beleuchten sein alles erzählen, nur nicht sein wirkliches Leben“, und der Erzähler in Mein Name sei Gantenbein (1964) Leben und Werk, mit besonderem Augenmerk auf seinen erlernten Beruf als Architekt und dessen meint: "Jeder Mensch erfindet sich früher oder später eine Geschichte, die er für sein Leben hält." Einfluss auf sein Schreiben. Unter den Teilnehmern sein enger Freund Peter Bichsel, seine Tochter Auch in Frischs drittem großen Roman Homo faber (1957), ebenso wie in seinen berühmtesten Ursula Priess und der Frisch-Biograf Volker Hage. Theaterstücken Andorra (1961) und Biedermann und die Brandstifter (1958) geht es zentral um das Ringen zwischen persönlicher Identität und Selbstentfremdung. Von Philipp Schöbi Eines Architekten tägliches Brot ist der Entwurf. Das Ausdenken von Möglichkeiten und Varianten, das Korrigieren oder Verwerfen, die Niederlage als Normalfall. Max Frisch hatte diesen Beruf erlernt. Österreichische Wurzeln Sein Leben glich einer fortdauernden Anprobe von Entwürfen. Das Motto „Ich probiere Geschichten Sein Großvater väterlicherseits stammte aus Österreich. Franz Frisch (1838-1892) war um 1870 als an wie Kleider!“ seiner Romanfigur Gantenbein durchzieht sein Denken, Schreiben und Handeln, im junger Sattler in die Schweiz ausgewandert und hatte in Zürich, so Max Frisch (MF), „eine Hiesige, Rückblick de facto auch seinen Lebensweg.