Georg Von Der Gabelentz the Published Version of This Article Is In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia

— Early draft. Please do not quote, cite, or redistribute without written permission of the authors. — How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia After 1815∗ Thilo R. Huningy and Nikolaus Wolfz Abstract We analyze the formation oft he German Zollverein as an example how geography can shape institutional change. We show how the redrawing of the European map at the Congress of Vienna—notably Prussia’s control over the Rhineland and Westphalia—affected the incentives for policymakers to cooperate. The new borders were not endogenous. They were at odds with the strategy of Prussia, but followed from Britain’s intervention at Vienna regarding the Polish-Saxon question. For many small German states, the resulting borders changed the trade-off between the benefits from cooperation with Prussia and the costs of losing political control. Based on GIS data on Central Europe for 1818–1854 we estimate a simple model of the incentives to join an existing customs union. The model can explain the sequence of states joining the Prussian Zollverein extremely well. Moreover we run a counterfactual exercise: if Prussia would have succeeded with her strategy to gain the entire Kingdom of Saxony instead of the western provinces, the Zollverein would not have formed. We conclude that geography can shape institutional change. To put it different, as collateral damage to her intervention at Vienna,”’Britain unified Germany”’. JEL Codes: C31, F13, N73 ∗We would like to thank Robert C. Allen, Nicholas Crafts, Theresa Gutberlet, Theocharis N. Grigoriadis, Ulas Karakoc, Daniel Kreßner, Stelios Michalopoulos, Klaus Desmet, Florian Ploeckl, Kevin H. -

Ideas of Language from Antiquity to Modern Times

Late 18 th century: comparative linguistics The discovery of Sanskrit... Ideas of Language from – Charles Wilkins: the first European who really knew Skt., translated Bhagavad-Ghita & Hitopadesha; typographer! Antiquity to Modern Times András Cser BBNAN-14600, Elective seminar in linguistics 1 Mon 10:00–11:30, rm 301 Late 18 th century: comparative linguistics Late 18 th century: comparative linguistics The discovery of Sanskrit... "The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a – Charles Wilkins: the first European who really knew Skt., wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more translated Bhagavad-Ghita & Hitopadesha; typographer! copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than – Nathaniel Brassey Halhead: derives Latin and Greek either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both from Skt. in a private letter (1779) in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong – Henry T. Colebrooke, professor of Skt at Fort William indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, – Alexander Hamilton, army cadet, on return first professor without believing them to have sprung from some common of Skt in Europe (Hertford College, Oxford) source, which, perhaps, no longer exists: there is a similar – Sir William Jones, judge, Persian expert, first president of reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that Asiatic Society, often seen as the founder of Indo- both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very European -

Language and Geometry a Method for Comparing the Genealogical and Structural Relatedness Between Pairs of European Languages

4 Journal for EuroLinguistiX 11 (2014): 4-13 Jacques François Language and Geometry A Method for Comparing the Genealogical and Structural Relatedness between Pairs of European Languages Abstract In the second half of 19th century, two German linguists, August Schleicher and Johannes Schmidt, worked out a method of genealogical comparison of the Indo-European languages which crucially rested on inflectional morphology and phonology (so-called Stammbaum hypothesis by Schleicher) supplemented by wave-like spreading (so-called wave-hypothesis by Schmidt) of such properties amongst geographically neighbouring languages. First, this method is applied to four European languages: Dutch, English, French and German. Next, a list of 18 structural properties of the four languages is collected in order to assess the structural relatedness of each pair of languages. The two resulting charts turn out to be similar concerning the proximity between Dutch vs. German, but quite disparate concerning the latter vs. English and French. The structural chart is insightful, but weighting the collected structural properties (on the basis of criteria to be justified) might generate a differently shaped chart. Sommaire Dans la seconde moitié du 19e siècle, deux linguistes allemands, August Schleicher et Johannes Schmidt, ont élaboré une méthode de comparaison généalogique des langues indo-européennes essentiellement basée sur la morphologie flexionnelle et la phonologie (hypothèse du Stammbaum de Schleicher) complétée par une dissémination ‘ondulatoire’ (hypothèse de Schmidt) de propriétés de ce type entre des langues géographiquement voisines. En premier lieu, cette méthode est appliquée à quatre langues européennes : allemand, anglais, français et néerlandais. Ensuite, une liste de 18 propriétés structurales des quatre langues est établie afin de mesurer la proximité structurale entre celles-ci. -

Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School April 2021 Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis William A. B. Parkhurst University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Parkhurst, William A. B., "Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis by William A. B. Parkhurst A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Joshua Rayman, Ph.D. Lee Braver, Ph.D. Vanessa Lemm, Ph.D. Alex Levine, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 16th, 2021 Keywords: Fredrich Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, History of Philosophy, Continental Philosophy Copyright © 2021, William A. B. Parkhurst Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my mother, Carol Hyatt Parkhurst (RIP), who always believed in my education even when I did not. I am also deeply grateful for the support of my father, Peter Parkhurst, whose support in varying avenues of life was unwavering. I am also deeply grateful to April Dawn Smith. It was only with her help wandering around library basements that I first found genetic forms of diplomatic transcription. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Conducting Census Research in Archives in Germany, France, and Poland

Conducting Census Research in Archives in Germany, France, and Poland Should you be fortunate to have the time and money make the copies, you may need to exercise great to invest in a trip to Europe to pursue census records, patience. Filling out copy requests takes time. The you have a lot of work to do before you go. Finding a copies will usually be made after you leave and copy of the book Researching in Germany would be the will be mailed or email ed to you with an invoic e best way to start, because it was written with you in several weeks later. mind. In general, you would do well to consider the 13. Send thank-you cards to anybody who helped you following points: 1 significantly. 1. Begin planning your trip at least six months in 1 Of course, this list deals only with things you advance. should consider that regard archives. There are 2. Write out specific goals for your research. many more aspects of the trip that must be carefully 3. If possible, study the online catalog of any archive addressed, such as air and ground travel, lodging, and that might have the documents you need. meals. If planned well, such a trip can be the adven 4. Communicate carefully with each archive regard ture of a lifetime for a family history researcher. ing your research goals. 5. Know the archive's schedule for visitors; many have different hours ( or no hours) on different Notes days of the week ( and watch out for holidays). -

What Is General Linguistics?

Introduction ‘What is General Linguistics?’ The first full professor of General Linguistics at the University of Amsterdam, Anton Reichling (1898-1986), asked this question in 1947 in the title of his inaugural lecture. Reichling presented his audience with a bird’s-eye view of eight centuries of answers to his question, which he all re garded as wrong, mainly because of the attempt to find the ‘generality’ of general linguistics in the wrong place: either in aprioristic ideas on ‘general grammar’ (the earlier answers) or in reductionist appeals to non-linguistic principles (the later answers). And yet, according to Reichling, one man had already been on the right track, that of ‘autonomous generality’, years ago. This man was Georg von der Gabelentz (1840-1893), and his answer can be found in his book Die Sprachwissenschaft, Ihre Aufgaben, Methoden und bisherigen Ergebnisse, first published in 1891. Reichling quoted a long passage from this book, in which Gabelentz envisages a new pro gramme for language typology and which begins as follows:1 (i) Every language is a system, of which all parts organically relate to and cooperate with each other. One has to suppose that none of these parts may be lacking, or diff erent, without the whole being changed. Reichling concluded that Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913), the founder of mod ern general linguistics, had an almost visionary predecessor. Reichling’s comments form a good starting point for the subject I want to explore, the rise of general linguistics, with a focus on Gabelentz. They are linked to the following facts and issues, all of which are relevant to this theme: This content downloaded from 193.194.76.5 on Sat, 22 May 2021 07:13:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Els Elffers a) A European university established its fi rst chair in General Linguistics as late as 1947. -

<B>The Public Mood in Bavaria and Other Federal States, Through British Eyes (December 3, 1866)</B><E>

Volume 4. Forging an Empire: Bismarckian Germany, 1866-1890 The Public Mood in Bavaria and Other Federal States through British Eyes (December 3, 1866) After Prussia’s victory in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, the future lay open. Annexations in the north and the forced incorporation of the Kingdom of Saxony into the North German Confederation had vastly increased Prussia’s power and prestige; but still the southern German states remained independent. Since many Germans longed for a unified Germany, there was a great deal of speculation about where Bismarck’s expansionist plans would lead next. The following appraisal was written in December 1866 by Sir Henry Francis Howard (1809-1898), who served as the British envoy to Bavaria from 1866 to 1872. In this confidential report to the British Foreign Office, Howard sums up the mood in the annexed territories and in the southern states. Although it was in Britain’s interest for Prussia to provide a bulwark against possible French aggression in the future, other diplomatic complications clouded the overall picture. Domestically, Prussia’s hegemony was proving difficult to swallow by those who had fought on the losing side during the war. Howard accurately describes the bitterness felt towards Prussia in many parts of Germany at the time. Munich, 3 December 1866 My Lord, The Prussian annexations have no doubt considerably advanced the unification of Germany, but the process of consolidation will be a slow one, because they were effected by conquest and contrary to the will of the population of the annexed countries, and the general state of Germany after the war is anything but settled or satisfactory. -

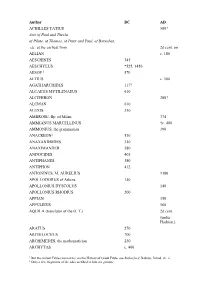

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

Fabulous Firsts: Saxony (July 1, 1850)

Fabulous Firsts: Saxony (July 1, 1850) (As with many of our Fabulous Firsts features, this article is based on an ar- ticle by B. W. H. Poole, this one from a German States booklet published by Mekeel’s. JFD.) * * * * * Saxony is a kingdom of Germany, being fifth in area and third in population among the states of the empire. It is surrounded by Bohemia, Silesia, Prussian Saxony, and the minor Saxon States and has a total area of 5,787 square miles. The population grows fast and had nearly quadrupled in the period 1815-1900. At the present time it has nearly reached the five million mark and is the most densely peopled country in Europe. The River Elbe divides the kingdom into two almost equal parts, both hilly and both well watered. The pre- dominating geographical feature of the western half is the Erzgebirge (2,500 feet) separating it from Bohemia; of the eastern half, offsets of the Riesengebirge, and the sandstone formation, above Dresden, known as the Saxon Switzerland. Agriculture is highly developed, though most of the farms are small. Saxony’s chief interests are, however, manufacturing and mining. Coal, iron, cobalt, tin, copper, lead and silver are all found, the latter having been mined at Freiberg since the 12th century. The people are in part of Slav descent, but German- ised. Amongst them are between 50,000 and 60,000 Wends (pure Slavs). Education stands at a high level, the university at Leipzig, for instance, being one of the most important educational centres of the empire. The capital is Dresden, while the three largest towns are Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz. -

Verifying the Consistency of the Digitized Indo-European Sound Law System Generating the Data of the 120 Most Archaic Languages from Proto-Indo-European

Verifying the Consistency of the Digitized Indo-European Sound Law System Generating the Data of the 120 Most Archaic Languages from Proto-Indo-European Jouna Pyysalo, Aleksi Sahala, and Mans Hulden ABSTRACT: Using state-of-the-art finite-state technology (FST) we automatically generate data of the some 120 most archaic Indo-European (IE) languages from reconstructed Proto-Indo-European (PIE) by means of digitized sound laws. The accuracy rate of the automatic generation of the data exceeds 99%, which also applies in the generation of new data that were not observed when the rules representing the sound laws were originally compiled. After testing and verifying the consistency of the sound law system with regard to the IE data and the PIE reconstruction, we report the following results: a) The consistency of the digitized sound law system generating the data of the 120 most archaic Indo-European languages from Proto-Indo-European is verifiable. b) The primary objective of Indo-European linguistics, a reconstruction theory of PIE in essence equivalent to the IE data (except for a limited set of open research problems), has been provably achieved. The results are fully explicit, repeatable, and verifiable. 1. On the digitalization of Indo-European sound laws with finite-state technology (FST) 1.1 Sir William JONES’ (1788) groundbreaking announcement of a genetic relationship between European languages including Greek and Latin, Sanskrit, and other language groups and the existence of a common ancestor of these Indo- European (IE) languages marks the birth of modern comparative linguistics. Soon after, the pioneers Rasmus RASK, Franz BOPP, and others confirmed the existence of systematic correspondences between the ‘letters’ (phonemes) of the IE languages, thus verifying Sir William’s initial assessment: the Indo-European languages are indeed genetically related and descended from a common source, now known as Proto-Indo-European (PIE). -

La Filología, La Lingüística Y Las Leyes De La Evolución

Ennis, Juan Antonio La filología, la lingüística y las leyes de la evolución. Curtius y Brugmann, lindes y deslindes Revista argentina de historiografía lingüística 2018, vol. 10, nro. 2, p. 93-105 Ennis, J. (2018). La filología, la lingüística y las leyes de la evolución. Curtius y Brugmann, lindes y deslindes. Revista argentina de historiografía lingüística, 10 (2), 93-105. En Memoria Académica. Disponible en: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.11606/pr.11606.pdf Información adicional en www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Revista argentina de historiografía lingüística, X, 2, 93-105, 2018 La filología, la lingüística y las leyes de la evolución. Curtius y Brugmann, lindes y deslindes Philology, linguistics and the laws of evolution. Curtius and Brugmann, boundaries and demarcations Juan Antonio Ennis∗ IdIHCS, UNLP-CONICET Abstract In this paper we provide an introduction to the two German texts translated for this issue of RAHL. These are two interventions by Georg Curtius and Karl Brugmann, dated in 1862 and 1885 respectively, both devoted to dealing with the complex relationship between philology and linguistics. To do so, we first sketch a review of different features of the discussion on the relationship between both disciplines throughout the 19th century in the German-speaking academic space. Then, we present some basic issues that should contribute to situate the texts in their own context. Key words: Georg Curtius, Karl Brugmann, Philology, Linguistics, Neogrammarians. Resumen Se ofrece aquí una introducción a los dos textos cuya traducción se ofrece en este mismo número, sendas intervenciones de Georg Curtius y Karl Brugmann sobre la relación entre la filología y la lingüística, de 1862 y 1885 respectivamente.