© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1-1 Introduction

Glime, J. M. 2017. Introduction. Chapt. 1. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. Physiological Ecology. Ebook sponsored 1-1-1 by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 25 April 2021 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 1-1 INTRODUCTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Thinking on a New Scale .................................................................................................................................... 1-1-2 Adaptations to Land ............................................................................................................................................ 1-1-3 Minimum Size..................................................................................................................................................... 1-1-5 Do Bryophytes Lack Diversity?.......................................................................................................................... 1-1-6 The "Moss".......................................................................................................................................................... 1-1-7 What's in a Name?............................................................................................................................................... 1-1-8 Phyla/Divisions............................................................................................................................................ 1-1-8 Role of Bryology................................................................................................................................................ -

Systema Naturae∗

Systema Naturae∗ c Alexey B. Shipunov v. 5.802 (June 29, 2008) 7 Regnum Monera [ Bacillus ] /Bacteria Subregnum Bacteria [ 6:8Bacillus ]1 Superphylum Posibacteria [ 6:2Bacillus ] stat.m. Phylum 1. Firmicutes [ 6Bacillus ]2 Classis 1(1). Thermotogae [ 5Thermotoga ] i.s. 2(2). Mollicutes [ 5Mycoplasma ] 3(3). Clostridia [ 5Clostridium ]3 4(4). Bacilli [ 5Bacillus ] 5(5). Symbiobacteres [ 5Symbiobacterium ] Phylum 2. Actinobacteria [ 6Actynomyces ] Classis 1(6). Actinobacteres [ 5Actinomyces ] Phylum 3. Hadobacteria [ 6Deinococcus ] sed.m. Classis 1(7). Hadobacteres [ 5Deinococcus ]4 Superphylum Negibacteria [ 6:2Rhodospirillum ] stat.m. Phylum 4. Chlorobacteria [ 6Chloroflexus ]5 Classis 1(8). Ktedonobacteres [ 5Ktedonobacter ] sed.m. 2(9). Thermomicrobia [ 5Thermomicrobium ] 3(10). Chloroflexi [ 5Chloroflexus ] ∗Only recent taxa. Viruses are not included. Abbreviations and signs: sed.m. (sedis mutabilis); stat.m. (status mutabilis): s., aut i. (superior, aut interior); i.s. (incertae sedis); sed.p. (sedis possibilis); s.str. (sensu stricto); s.l. (sensu lato); incl. (inclusum); excl. (exclusum); \quotes" for environmental groups; * (asterisk) for paraphyletic taxa; / (slash) at margins for major clades (\domains"). 1Incl. \Nanobacteria" i.s. et dubitativa, \OP11 group" i.s. 2Incl. \TM7" i.s., \OP9", \OP10". 3Incl. Dictyoglomi sed.m., Fusobacteria, Thermolithobacteria. 4= Deinococcus{Thermus. 5Incl. Thermobaculum i.s. 1 4(11). Dehalococcoidetes [ 5Dehalococcoides ] 5(12). Anaerolineae [ 5Anaerolinea ]6 Phylum 5. Cyanobacteria [ 6Nostoc ] Classis 1(13). Gloeobacteres [ 5Gloeobacter ] 2(14). Chroobacteres [ 5Chroococcus ]7 3(15). Hormogoneae [ 5Nostoc ] Phylum 6. Bacteroidobacteria [ 6Bacteroides ]8 Classis 1(16). Fibrobacteres [ 5Fibrobacter ] 2(17). Chlorobi [ 5Chlorobium ] 3(18). Salinibacteres [ 5Salinibacter ] 4(19). Bacteroidetes [ 5Bacteroides ]9 Phylum 7. Spirobacteria [ 6Spirochaeta ] Classis 1(20). Spirochaetes [ 5Spirochaeta ] s.l.10 Phylum 8. Planctobacteria [ 6Planctomyces ]11 Classis 1(21). -

Fossils and Plant Phylogeny1

American Journal of Botany 91(10): 1683±1699. 2004. FOSSILS AND PLANT PHYLOGENY1 PETER R. CRANE,2,5 PATRICK HERENDEEN,3 AND ELSE MARIE FRIIS4 2Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, UK; 3Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington DC 20052 USA; 4Department of Palaeobotany, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, S-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden Developing a detailed estimate of plant phylogeny is the key ®rst step toward a more sophisticated and particularized understanding of plant evolution. At many levels in the hierarchy of plant life, it will be impossible to develop an adequate understanding of plant phylogeny without taking into account the additional diversity provided by fossil plants. This is especially the case for relatively deep divergences among extant lineages that have a long evolutionary history and in which much of the relevant diversity has been lost by extinction. In such circumstances, attempts to integrate data and interpretations from extant and fossil plants stand the best chance of success. For this to be possible, what will be required is meticulous and thorough descriptions of fossil material, thoughtful and rigorous analysis of characters, and careful comparison of extant and fossil taxa, as a basis for determining their systematic relationships. Key words: angiosperms; fossils; paleobotany; phylogeny; spermatophytes; tracheophytes. Most biological processes, such as reproduction or growth distic context, neither fossils nor their stratigraphic position and development, can only be studied directly or manipulated have any special role in inferring phylogeny, and although experimentally using living organisms. Nevertheless, much of more complex models have been developed (see Fisher, 1994; what we have inferred about the large-scale processes of plant Huelsenbeck, 1994), these have not been widely adopted. -

Globally Widespread Bryophytes, but Rare in Europe

Portugaliae Acta Biol. 20: 11-24. Lisboa, 2002 GLOBALLY WIDESPREAD BRYOPHYTES, BUT RARE IN EUROPE Tomas Hallingbäck Swedish Threatened Species Unit, P.O. Box 7007, SE-75007 Uppsala, Sweden. [email protected] Hallingbäck, T. (2002). Globally widespread bryophytes, but rare in Europe. Portugaliae Acta Biol. 20: 11-24. The need to save not only globally threatened species, but also regionally rare and declining species in Europe is discussed. One rationale of red-listing species regionally is to be preventive and to counteract the local species extinction process. There is also a value in conserving populations at the edge of their geographical range and this is discussed in terms of genetic variation. Another reason is the political willingness of acting locally rather than globally. Among the rare and non-endemic species in Europe, some are rare and threatened both in Europe and elsewhere, others are more common outside Europe and a third group is locally common within Europe but rare in the major part. How much conservation effort should be put on these three European non-endemic species groups is briefly discussed, as well as why bryophytes are threatened. A discussion is given, for example, of how a smaller total distribution range, decreasing density of localities, smaller sites, less substrate and lower habitat quality affect the survival of sensitive species. This is also compared with species that have either high or low dispersal capacity or different longevity of either vegetative parts or spores. Examples from Sweden are given. Key words: Bryophytes, rarity, Europe, dispersal capacity, Sweden. Hallingbäck, T. (2002). -

Plant Life MagillS Encyclopedia of Science

MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE Volume 4 Sustainable Forestry–Zygomycetes Indexes Editor Bryan D. Ness, Ph.D. Pacific Union College, Department of Biology Project Editor Christina J. Moose Salem Press, Inc. Pasadena, California Hackensack, New Jersey Editor in Chief: Dawn P. Dawson Managing Editor: Christina J. Moose Photograph Editor: Philip Bader Manuscript Editor: Elizabeth Ferry Slocum Production Editor: Joyce I. Buchea Assistant Editor: Andrea E. Miller Page Design and Graphics: James Hutson Research Supervisor: Jeffry Jensen Layout: William Zimmerman Acquisitions Editor: Mark Rehn Illustrator: Kimberly L. Dawson Kurnizki Copyright © 2003, by Salem Press, Inc. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner what- soever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, Inc., P.O. Box 50062, Pasadena, California 91115. Some of the updated and revised essays in this work originally appeared in Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science (1991), Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science, Supplement (1998), Natural Resources (1998), Encyclopedia of Genetics (1999), Encyclopedia of Environmental Issues (2000), World Geography (2001), and Earth Science (2001). ∞ The paper used in these volumes conforms to the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48-1992 (R1997). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magill’s encyclopedia of science : plant life / edited by Bryan D. -

Earliest Record of Megaphylls and Leafy Structures, and Their Initial Diversification

Review Geology August 2013 Vol.58 No.23: 27842793 doi: 10.1007/s11434-013-5799-x Earliest record of megaphylls and leafy structures, and their initial diversification HAO ShouGang* & XUE JinZhuang Key Laboratory of Orogenic Belts and Crustal Evolution, School of Earth and Space Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China Received January 14, 2013; accepted February 26, 2013; published online April 10, 2013 Evolutionary changes in the structure of leaves have had far-reaching effects on the anatomy and physiology of vascular plants, resulting in morphological diversity and species expansion. People have long been interested in the question of the nature of the morphology of early leaves and how they were attained. At least five lineages of euphyllophytes can be recognized among the Early Devonian fossil plants (Pragian age, ca. 410 Ma ago) of South China. Their different leaf precursors or “branch-leaf com- plexes” are believed to foreshadow true megaphylls with different venation patterns and configurations, indicating that multiple origins of megaphylls had occurred by the Early Devonian, much earlier than has previously been recognized. In addition to megaphylls in euphyllophytes, the laminate leaf-like appendages (sporophylls or bracts) occurred independently in several dis- tantly related Early Devonian plant lineages, probably as a response to ecological factors such as high atmospheric CO2 concen- trations. This is a typical example of convergent evolution in early plants. Early Devonian, euphyllophyte, megaphyll, leaf-like appendage, branch-leaf complex Citation: Hao S G, Xue J Z. Earliest record of megaphylls and leafy structures, and their initial diversification. Chin Sci Bull, 2013, 58: 27842793, doi: 10.1007/s11434- 013-5799-x The origin and evolution of leaves in vascular plants was phology and evolutionary diversification of early leaves of one of the most important evolutionary events affecting the basal euphyllophytes remain enigmatic. -

THE EVOLUTION of XYLEM ANATOMY in EARLY TRACHEOPHYTES by ELISABETH ANNE BERGMAN

Conquering the terrestrial environment: the evolution of xylem anatomy in early tracheophytes Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Bergman, Elisabeth Anne Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 03:01:29 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/626731 CONQUERING THE TERRESTRIAL ENVIRONMENT: THE EVOLUTION OF XYLEM ANATOMY IN EARLY TRACHEOPHYTES By ELISABETH ANNE BERGMAN ____________________ A Thesis Submitted to The Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelors Degree With Honors in Biology with an Emphasis in Biomedical Sciences THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA D E C E M B E R 2 0 1 7 Approved by: ____________________________ Dr. Brian Enquist Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Acknowledgements Many thanks go to all of those who made contributions, big and small, to my honors thesis, and more notably, my education. Foremost, I thank Dr. Brian Enquist for accepting me into his lab and serving as my mentor for two years. I appreciate all of the time he put in to meet with me and help me to develop my honors thesis. Additional thanks go to Dr. Sean Michaletz who first introduced me to the work that would eventually become my honors thesis. From the University of Santa Cruz, California, I thank Dr. -

Scouring-Rush Horsetail Scientific Name: Equisetum Hyemale Order

Common Name: Scouring-rush Horsetail Scientific Name: Equisetum hyemale Order: Equisetales Family: Equisetaceae Wetland Plant Status: Facultative Ecology & Description Scouring-rush horsetail is an evergreen, perennial plant that completes a growing season in two years. At maturity, scouring-rush horsetail usually averages 3 feet in height but can be range anywhere from 2 to 5 feet. It can survive in a variety of environments. One single plant can spread 6 feet in diameter. It has cylindrical stems that averages a third of an inch in diameter. Noticeably spotted are the jointed unions that are located down the plant. The stems are hollow and don’t branch off into additional stems. Also, scouring- rush horsetail has rough ridges that run longitudinal along the stem. Although not covered in leaves, tiny leaves are joined together around the stem which then forms a black or green band, or sheath at each individual joint on the stem. This plant has an enormous root system that can reach 6 feet deep and propagates in two ways: rhizomes and spores. Incredibly, due to the fact that this plant is not full of leaves, it is forced to photosynthesize through the stem rather than leaves. Habitat Scouring-rush horsetail is highly tolerant of tough conditions. It can survive and thrive in full sun or part shade and can successfully grow in a variety of soil types. It can also grow in moderate to wet soils, and can survive in up to 4 inches of water. Distribution Scouring-rush horsetail can be found throughout the United States, Eurasia, and Canada. -

System Klasyfikacji Organizmów

1 SYSTEM KLASYFIKACJI ORGANIZMÓW Nie ma dziś ogólnie przyjętego systemu klasyfikacji organizmów. Nie udaje się osiągnąć zgodności nie tylko w odniesieniu do zakresów i rang poszczególnych taksonów, ale nawet co do zasad metodologicznych, na których klasyfikacja powinna być oparta. Zespołowe dzieła przeglądowe z reguły prezentują odmienne i wzajemnie sprzeczne podejścia poszczególnych autorów, bez nadziei na consensus. Nie ma więc mowy o skompilowaniu jednolitego schematu klasyfikacji z literatury i system przedstawiony poniżej nie daje nadziei na zaakceptowanie przez kogokolwiek poza kompilatorem. Przygotowany został w oparciu o kilka zasad (skądinąd bardzo kontrowersyjnych): (1) Identyfikowanie ga- tunków i ich klasyfikowanie w jednostki rodzajowe, rodzinowe czy rzędy jest zadaniem specjalistów i bez szcze- gółowych samodzielnych studiów nie można kwestionować wyników takich badań. (2) Podział świata żywego na królestwa, typy, gromady i rzędy jest natomiast domeną ewolucjonistów i dydaktyków. Powody, które posłużyły do wydzielenia jednostek powinny być jasno przedstawialne i zrozumiałe również dla niespecjalistów, albowiem (3) podstawowym zadaniem systematyki jest ułatwianie laikom i początkującym badaczom poruszanie się w obezwładniającej złożoności świata żywego. Wątpliwe jednak, by wystarczyło to do stworzenia zadowalającej klasyfikacji. W takiej sytuacji można jedynie przypomnieć, że lepszy ułomny system, niż żaden. Królestwo PROKARYOTA Chatton, 1938 DNA wyłącznie w postaci kolistej (genoforów), transkrypcja nie rozdzielona przestrzennie od translacji – rybosomy w tym samym przedzia- le komórki, co DNA. Oddział CYANOPHYTA Smith, 1938 (Myxophyta Cohn, 1875, Cyanobacteria Stanier, 1973) Stosunkowo duże komórki, dwuwarstwowa błona (Gram-ujemne), wewnętrzna warstwa mureinowa. Klasa CYANOPHYCEAE Sachs, 1874 Rząd Stigonematales Geitler, 1925; zigen – dziś Chlorofil a na pojedynczych tylakoidach. Nitkowate, rozgałęziające się, cytoplazmatyczne połączenia mię- Rząd Chroococcales Wettstein, 1924; 2,1 Ga – dziś dzy komórkami, miewają heterocysty. -

Ferns and Fern Allies

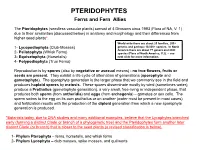

PTERIDOPHYTES Ferns and Fern Allies The Pteridophytes (seedless vascular plants) consist of 4 Divisions circa 1993 (Flora of NA, V. 1) due to their similarities (discussed below) in anatomy and morphology and their differences from higher seed plants*. World-wide there are about 25 families, 255+ 1- Lycopodiophyta (Club-Mosses) genera, and perhaps 10,000+ species. In North America there are about 77 genera and 440+ 2- Psilotophyta (Whisk Ferns) species (Flora of North America, V.2). – see 3- Equisetophyta (Horsetails) next slide for more information. 4- Polypodiophyta (True Ferns) Reproduction is by spores (also by vegetative or asexual means) - no true flowers, fruits or seeds are present. They exhibit a life cycle of alternation of generations (sporophyte and gametophyte). The sporophyte generation is the larger phase that we commonly see in the field and produces haploid spores by meiosis. These spores disseminate mostly by wind (sometimes water), produce a Prothallus (gametophyte generation), a very small, free-living or independent phase, that produces both sperm (from antheridia) and eggs (from archegonia) – gametes or sex cells. The sperm swims to the egg on its own prothallus or on another (water must be present in most cases) and fertilization results with the production of the diploid generation from which a new sporophyte generation is produced. *Botanists today, due to DNA studies and many additional examples, believe that the Lycophytes branched early (forming a distinct Clade or branch of a phylogenetic tree) and the Pteridophytes form another later distinct Clade (or branch) that is closer to the seed plants (a revised classification is below). -

Rare Or Threatened Vascular Plant Species of Wollemi National Park, Central Eastern New South Wales

Rare or threatened vascular plant species of Wollemi National Park, central eastern New South Wales. Stephen A.J. Bell Eastcoast Flora Survey PO Box 216 Kotara Fair, NSW 2289, AUSTRALIA Abstract: Wollemi National Park (c. 32o 20’– 33o 30’S, 150o– 151oE), approximately 100 km north-west of Sydney, conserves over 500 000 ha of the Triassic sandstone environments of the Central Coast and Tablelands of New South Wales, and occupies approximately 25% of the Sydney Basin biogeographical region. 94 taxa of conservation signiicance have been recorded and Wollemi is recognised as an important reservoir of rare and uncommon plant taxa, conserving more than 20% of all listed threatened species for the Central Coast, Central Tablelands and Central Western Slopes botanical divisions. For a land area occupying only 0.05% of these divisions, Wollemi is of paramount importance in regional conservation. Surveys within Wollemi National Park over the last decade have recorded several new populations of signiicant vascular plant species, including some sizeable range extensions. This paper summarises the current status of all rare or threatened taxa, describes habitat and associated species for many of these and proposes IUCN (2001) codes for all, as well as suggesting revisions to current conservation risk codes for some species. For Wollemi National Park 37 species are currently listed as Endangered (15 species) or Vulnerable (22 species) under the New South Wales Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995. An additional 50 species are currently listed as nationally rare under the Briggs and Leigh (1996) classiication, or have been suggested as such by various workers. Seven species are awaiting further taxonomic investigation, including Eucalyptus sp. -

Species List For: Labarque Creek CA 750 Species Jefferson County Date Participants Location 4/19/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey

Species List for: LaBarque Creek CA 750 Species Jefferson County Date Participants Location 4/19/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey 5/15/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey 5/16/2006 Nels Holmberg, George Yatskievych, and Rex Plant Survey Hill 5/22/2006 Nels Holmberg and WGNSS Botany Group Plant Survey 5/6/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey Multiple Visits Nels Holmberg, John Atwood and Others LaBarque Creek Watershed - Bryophytes Bryophte List compiled by Nels Holmberg Multiple Visits Nels Holmberg and Many WGNSS and MONPS LaBarque Creek Watershed - Vascular Plants visits from 2005 to 2016 Vascular Plant List compiled by Nels Holmberg Species Name (Synonym) Common Name Family COFC COFW Acalypha monococca (A. gracilescens var. monococca) one-seeded mercury Euphorbiaceae 3 5 Acalypha rhomboidea rhombic copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 1 3 Acalypha virginica Virginia copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 2 3 Acer negundo var. undetermined box elder Sapindaceae 1 0 Acer rubrum var. undetermined red maple Sapindaceae 5 0 Acer saccharinum silver maple Sapindaceae 2 -3 Acer saccharum var. undetermined sugar maple Sapindaceae 5 3 Achillea millefolium yarrow Asteraceae/Anthemideae 1 3 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry Ranunculaceae 8 5 Adiantum pedatum var. pedatum northern maidenhair fern Pteridaceae Fern/Ally 6 1 Agalinis gattingeri (Gerardia) rough-stemmed gerardia Orobanchaceae 7 5 Agalinis tenuifolia (Gerardia, A. tenuifolia var. common gerardia Orobanchaceae 4 -3 macrophylla) Ageratina altissima var. altissima (Eupatorium rugosum) white snakeroot Asteraceae/Eupatorieae 2 3 Agrimonia parviflora swamp agrimony Rosaceae 5 -1 Agrimonia pubescens downy agrimony Rosaceae 4 5 Agrimonia rostellata woodland agrimony Rosaceae 4 3 Agrostis elliottiana awned bent grass Poaceae/Aveneae 3 5 * Agrostis gigantea redtop Poaceae/Aveneae 0 -3 Agrostis perennans upland bent Poaceae/Aveneae 3 1 Allium canadense var.