The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insight from the Sociology of Science

CHAPTER 7 INSIGHT FROM THE SOCIOLOGY OF SCIENCE Science is What Scientists Do It has been argued a number of times in previous chapters that empirical adequacy is insufficient, in itself, to establish the validity of a theory: consistency with the observable ‘facts’ does not mean that a theory is true,1 only that it might be true, along with other theories that may also correspond with the observational data. Moreover, empirical inadequacy (theories unable to account for all the ‘facts’ in their domain) is frequently ignored by individual scientists in their fight to establish a new theory or retain an existing one. It has also been argued that because experi- ments are conceived and conducted within a particular theoretical, procedural and instrumental framework, they cannot furnish the theory-free data needed to make empirically-based judgements about the superiority of one theory over another. What counts as relevant evidence is, in part, determined by the theoretical framework the evidence is intended to test. It follows that the rationality of science is rather different from the account we usually provide for students in school. Experiment and observation are not as decisive as we claim. Additional factors that may play a part in theory acceptance include the following: intuition, aesthetic considerations, similarity and consistency among theories, intellectual fashion, social and economic influences, status of the proposer(s), personal motives and opportunism. Although the evidence may be inconclusive, scientists’ intuitive feelings about the plausibility or aptness of particular ideas will make it appear convincing. The history of science includes many accounts of scientists ‘sticking to their guns’ concerning a well-loved theory in the teeth of evidence to the contrary, and some- times in the absence of any evidence at all. -

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

The Age of Empathy Is That Human Nature Offers a Dewa 9780307407764 5P 00 R1.Qxp 7/24/09 2:58 PM Page X

Age of Empathy 28/06/2011 10:16 Page 1 Age of Empathy 28/06/2011 10:16 Page 2 The Age of Empathy Copyright © 2009 by Frans de Waal This edition published by arrangement with Harmony Books, NATURE’S LESSONS an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division FOR A KINDER SOCIETY of Random House, Inc. First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Souvenir Press Ltd 43 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3PD This paperback edition first published in 2011 Reprinted 2012 The right of Frans de Waal to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Frans de Waal Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, With drawings by the author stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Copyright owner. ISBN 9780285640382 Design by Debbie Glasserman Souvenir Press This paperback published in 2019 First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Souvenir Press, an imprint of Profile Books Ltd 3 Holford Yard Bevin Way London WC1X 9HD www.profilebooks.com This edition published by arrangement with Harmony Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. Copyright © Frans de Waal, 2009, 2019 The right of Frans de Waal to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 All rights reserved. -

Biography (Modified, After Festetics 1983)

Konrad Lorenz’s Biography (modified, after Festetics 1983) 1903: Konrad Zacharias Lorenz (KL) was born in Altenberg /Austria on Nov. 7 as the last of three children of Emma Lorenz and Dr. Adolf Lorenz, professor for orthopedics at the Medical branch of the University of Vienna. In the same year the representative and spacious Altenberg family home was finished. 1907: KL starts keeping animals, such as spotted newts in aquaria, raises some ducklings and is not pleased by his first experiences with a dachshound. Niko Tinbergen, his lifelong colleague and friend, is born on April 15 in Den Haag, The Netherlands. 1909: KL enters elementary school and engages in systematic studies in crustaceans. 1910: Oskar Heinroth, biologist and founder of "Vergleichende Verhaltensforschung" (comparative ethology) from Berlin and fatherlike scientific mentor of the young KL publishes his classical paper on the ethology of ducks. 1915: KL enters highschool (Schottengymnasium Wien), keeps and breeds songbirds. 1918: Wallace Craig publishes the comparative ethology of Columbidae (pigeons), a classics of late US biologist Charles O. Whitman, who was like O. Heinroth, a founding father of comparative ethology. 1921: KL excels in his final exams. Together with friend Bernhard Hellmann, he observes and experiments with aggression in a cichlid (Herichthys cyanoguttatum). This was the base for KL's psychohydraulic model of motivation. 1922: Father Adolf sends KL to New York to take 2 semesters of medicine courses at the ColumbiaUniversity, but mainly to interrupt the relationship of KL with longterm girlfriend Gretl Gebhart, his later wife. This paternal attempt to influence the mate choice of KL failed. -

2862 001 OCR DBL ZIP 0.Pdf

, , .- GREAT SCIENTIFIC EXPERIMENTS Twenty Experiments that Changed our View of the World ROM HARRE Oxford New York OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1983 Whi'te Oalt OXford Um'wrsity Press, Waftoff Street, OXfordOX'2 6DP LondonGlasgov) New Yorn Toronto Delhi &mbay Calcutta Madras Knrachi Kuala'LumpurSingapore HangKnng·Tokyo Nairobi Dar es Salaam Cape Town Mel~urne Auckland and associates in Beirut Berlin [hac/an Mexico City Nicosia © Phaidon Press limited 1981 First published by Phaidon Press Limited /981 First issued as an Oxford University Press Paperback 1983 All n'ghts reserved. No port of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by atiy means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without ., the prior permission oj Oxford University Press This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall n(Jt,~by way oftrade or otherwise, be Jent, re-sold, hired out or otheruxse circulated without the pilblisher's prior consent in any fonn of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and ulithout a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Ham, Rom Great scientific experiments.-{Oxford paperbacks) 1. Science-experiments-History 1. Title SfJ1'.24 Q125 ISBN 0-19-286036-4 library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data , Harrl, Rmnimo. Great scientific experimetus. (Oxford paperbacks) " Biblwgraphy: p. Includes index. 1. Scieni:e-MethodlJ~(Ue studies. 2.-Science-Expen"men/$-PhI1osopf!y. 3. Science-Histo1y--Sources. 4. Scientists_Biograpf!y. I. Title. QI75.H32541983 507'.2 82';'19035 ISBN 0-19-286036-4 (pbk.) Printed in Great Britain by R. -

Synapses, Sea Slugs, and Psychiatry

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;70:1–3 1 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.1 on 1 January 2001. Downloaded from EDITORIAL Synapses, sea slugs, and psychiatry This year’s Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, announced literature than medicine. However, his Austrian contempo- on 9 October 2000, has gone to Arvid Carlsson, Paul Green- rary, Wagner von Jauregg, became the first psychiatrist lau- gard, and Eric Kandel. The citation states that the prize is reate in 1927 for his observations on the beneficial eVects shared for pioneering discoveries in slow synaptic transmis- of induced fever (for example, malaria) on the symptoms of sion, which are “crucial for an understanding of how the nor- neurosyphillis—not, it has to be said, a treatment that has mal functioning of the brain and how disturbances in this sig- stood the test of time. But European psychiatry at the fin de nal can give rise to neurological and psychiatric diseases” siecle was resolutely biological. Egaz Moniz, the Portu- (www.nobel.se/announcement/2000/medicine.html). Carls- guese neurosurgeon who developed psychosurgery, shared son proved the importance of dopamine as a neurotransmitter the prize in 1949, although the invention of arterial angio- and subsequently its role in Parkinson’s disease and graphy was perhaps a more enduring legacy. Neuroscien- schizophrenia. The strongest pillar of the dopamine theory of tists have been so rewarded on many occasions—but as in schizophrenia is the linear relation between potency of anti- this year, the contributions tended to be at the “basic” psychotic drugs and their dopamine antagonist potential. -

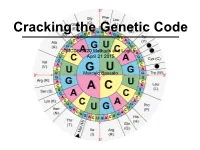

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

Korsgaard on De Waal

Morality and the Distinctiveness of Human Action Christine M. Korsgaard Harvard University What is different about the way we act that makes us, and not any other species, moral beings? - Frans de Waal1 A moral being is one who is capable of comparing his past and future actions or motives, and of approving or disapproving of them. We have no reason to suppose that any of the lower animals have this capacity. - Charles Darwin2 Two issues confront us. One concerns the truth or falsehood of what Frans de Waal calls “Veneer Theory.” This is the theory that morality is a thin veneer on an essentially amoral human nature. According to Veneer Theory, we are ruthlessly self-interested creatures, who conform to moral norms only to avoid punishment or disapproval, only when others are not watching us, or only when our commitment to these norms is not tested by strong temptation. The second concerns the question whether morality has its roots in our evolutionary past, or represents some sort of radical break with that past. De Waal proposes to address these two questions together, by adducing evidence that our closest relatives in the natural world exhibit tendencies that seem intimately related to morality – sympathy, empathy, sharing, conflict resolution, and so on. He concludes that the roots of 1 In Good-Natured: The Origins of Right and Wrong in Humans and Other Animals. Cambridge, USA: Harvard University Press, 1996, p. 111 2 In The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981, pp. 88-89. -

01De Waal Part I 1-80.Qxd

We approve and we disapprove because we cannot do otherwise. Can we help feeling pain when the fire burns us? Can we help sympathizing with our friends? —Edward Westermarck (1912 [1908]: 19) Why should our nastiness be the baggage of an apish past and our kindness uniquely human? Why should we not seek continuity with other animals for our “noble” traits as well? —Stephen Jay Gould (1980: 261) 0 omo homini lupus —“man is wolf to man”—is an ancient Roman proverb popularized by Thomas H Hobbes. Even though its basic tenet permeates large parts of law, economics, and political science, the proverb contains two major flaws. First, it fails to do justice to canids, which are among the most gregarious and cooperative ani mals on the planet (Schleidt and Shalter 2003). But even worse, the saying denies the inherently social nature of our own species. Social contract theory, and Western civilization with it, seems saturated with the assumption that we are asocial, even nasty creatures rather than the zoon politikon that Aristotle saw in us. Hobbes explicitly rejected the Aristotelian view by proposing that our ancestors started out autonomous and combative, establishing community life only when the cost of strife became unbearable. According to Hobbes, social life 4 FRANS DE WAAL never came naturally to us. He saw it as a step we took reluc tantly and “by covenant only, which is artificial” (Hobbes 1991 [1651]: 120). More recently, Rawls (1972) proposed a milder version of the same view, adding that humanity’s move toward sociality hinged on conditions of fairness, that is, the prospect of mutually advantageous cooperation among equals. -

In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick Discovered the Structure of DNA in the Now-Famous Scientific Narrative Known As the “Race Towards the Double Helix”

THE NARRATIVES OF SCIENCE: LITERARY THEORY AND DISCOVERY IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY PRIYA VENKATESAN In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA in the now-famous scientific narrative known as the “race towards the double helix”. Meanwhile in France, Roland Barthes published his first book, Writing Degree Zero, on literary theory, which became the intellectual precursor for the new human sciences that were developing based on Saussurean linguistics. The discovery by Watson and Crick of the double helix marked a definitive turning point in the development of the life sciences, paving the way for the articulation of the genetic code and the emergence of molecular biology. The publication by Barthes was no less significant, since it served as an exemplar for elucidating how literary narratives are structured and for formulating how textual material is constructed. As Françoise Dosse notes, Writing Degree Zero “received unanimous acclaim and quickly became a symptom of new literary demands, a break with tradition”.1 Both the work of Roland Barthes and Watson and Crick served as paradigms in their respective fields. Semiotics, the field of textual analysis as developed by Barthes in Writing Degree Zero, offered a new direction in the structuring of narrative whereby each distinct unit in a story formed a “code” or “isotopy” that categorizes the formal elements of the story. The historical concurrence of the discovery of the double helix and the publication of Writing Degree Zero may be mere coincidence, but this essay is an exploration of the intellectual influence that both events may have had on each other, since both the discovery of the double helix and Barthes’ publication gave expression to the new forms of knowledge 1 Françoise Dosse, History of Structuralism: The Rising Sign, 1945-1966, trans.