Pagina 1 Van 3 Scientific American: the Forgotten Code Cracker 12-11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insight from the Sociology of Science

CHAPTER 7 INSIGHT FROM THE SOCIOLOGY OF SCIENCE Science is What Scientists Do It has been argued a number of times in previous chapters that empirical adequacy is insufficient, in itself, to establish the validity of a theory: consistency with the observable ‘facts’ does not mean that a theory is true,1 only that it might be true, along with other theories that may also correspond with the observational data. Moreover, empirical inadequacy (theories unable to account for all the ‘facts’ in their domain) is frequently ignored by individual scientists in their fight to establish a new theory or retain an existing one. It has also been argued that because experi- ments are conceived and conducted within a particular theoretical, procedural and instrumental framework, they cannot furnish the theory-free data needed to make empirically-based judgements about the superiority of one theory over another. What counts as relevant evidence is, in part, determined by the theoretical framework the evidence is intended to test. It follows that the rationality of science is rather different from the account we usually provide for students in school. Experiment and observation are not as decisive as we claim. Additional factors that may play a part in theory acceptance include the following: intuition, aesthetic considerations, similarity and consistency among theories, intellectual fashion, social and economic influences, status of the proposer(s), personal motives and opportunism. Although the evidence may be inconclusive, scientists’ intuitive feelings about the plausibility or aptness of particular ideas will make it appear convincing. The history of science includes many accounts of scientists ‘sticking to their guns’ concerning a well-loved theory in the teeth of evidence to the contrary, and some- times in the absence of any evidence at all. -

The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021

More Fun Than Fun: The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021 An iconic photo of Konrad Lorenz with his favourite geese. Photo: Willamette Biology, CC BY-SA 2.0 This article is part of the ‘More Fun Than Fun‘ column by Prof Raghavendra Gadagkar. He will explore interesting research papers or books and, while placing them in context, make them accessible to a wide readership. RAGHAVENDRA GADAGKAR Among the books I read as a teenager, two completely changed my life. One was The Double Helix by Nobel laureate James D. Watson. This book was inspiring at many levels and instantly got me addicted to molecular biology. The other was King Solomon’s Ring by Konrad Lorenz, soon to be a Nobel laureate. The study of animal behaviour so charmingly and unforgettably described by Lorenz kindled in me an eternal love for the subject. The circumstances in which I read these two books are etched in my mind and may have partly contributed to my enthusiasm for them and their subjects. The Double Helix was first published in London in 1968 when I was a pre-university student (equivalent to 11th grade) at St Joseph’s college in Bangalore and was planning to apply for the prestigious National Science Talent Search Scholarship. By then, I had heard of the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA and its profound implications. I was also tickled that this momentous discovery was made in 1953, the year of my birth. I saw the announcement of Watson’s book on the notice board in the British Council Library, one of my frequent haunts. -

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Biochemistrystanford00kornrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Program in the History of the Biosciences and Biotechnology Arthur Kornberg, M.D. BIOCHEMISTRY AT STANFORD, BIOTECHNOLOGY AT DNAX With an Introduction by Joshua Lederberg Interviews Conducted by Sally Smith Hughes, Ph.D. in 1997 Copyright 1998 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Arthur Kornberg, M.D., dated June 18, 1997. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

Lecture Program

EARL W. SUTHERLAND LECTURE EARL W. SUTHERLAND LECTURE The Earl W. Sutherland Lecture Series was established by the SPONSORED BY: Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics in 1997 DEPARTMENT OF MOLECULAR PHYSIOLOGY AND BIOPHYSICS to honor Dr. Sutherland, a former member of this department and winner of the 1971 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. This series highlights important advances in cell signaling. ROBERT J. LEFKOWITZ, MD NOBEL PRIZE IN CHEMISTRY, 2012 SPEAKERS IN THIS SERIES HAVE INCLUDED: SEVEN TRANSMEMBRANE RECEPTORS Edmond H. Fischer (1997) Alfred G. Gilman (1999) Ferid Murad (2001) Louis J. Ignarro (2003) MARCH 31, 2016 Paul Greengard (2007) 4:00 P.M. 208 LIGHT HALL Eric Kandel (2009) Roger Tsien (2011) Michael S. Brown (2013) 867-2923-Institution-Discovery Lecture Series-Lefkowitz-BK-CH.indd 1 3/11/16 9:39 AM EARL W. SUTHERLAND, 1915-1974 ROBERT J. LEFKOWITZ, MD JAMES B. DUKE PROFESSOR, Earl W. Sutherland grew up in Burlingame, Kansas, a small farming community DUKE UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER that nourished his love for the outdoors and fishing, which he retained throughout INVESTIGATOR, HOWARD HUGHES MEDICAL INSTITUTE his life. He graduated from Washburn College in 1937 and then received his MEMBER, NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES M.D. from Washington University School of Medicine in 1942. After serving as a MEMBER, INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE medical officer during World War II, he returned to Washington University to train NOBEL PRIZE IN CHEMISTRY, 2012 with Carl and Gerty Cori. During those years he was influenced by his interactions with such eminent scientists as Louis Leloir, Herman Kalckar, Severo Ochoa, Arthur Kornberg, Christian deDuve, Sidney Colowick, Edwin Krebs, Theodore Robert J. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

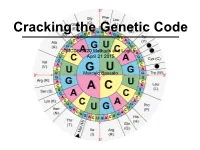

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick Discovered the Structure of DNA in the Now-Famous Scientific Narrative Known As the “Race Towards the Double Helix”

THE NARRATIVES OF SCIENCE: LITERARY THEORY AND DISCOVERY IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY PRIYA VENKATESAN In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA in the now-famous scientific narrative known as the “race towards the double helix”. Meanwhile in France, Roland Barthes published his first book, Writing Degree Zero, on literary theory, which became the intellectual precursor for the new human sciences that were developing based on Saussurean linguistics. The discovery by Watson and Crick of the double helix marked a definitive turning point in the development of the life sciences, paving the way for the articulation of the genetic code and the emergence of molecular biology. The publication by Barthes was no less significant, since it served as an exemplar for elucidating how literary narratives are structured and for formulating how textual material is constructed. As Françoise Dosse notes, Writing Degree Zero “received unanimous acclaim and quickly became a symptom of new literary demands, a break with tradition”.1 Both the work of Roland Barthes and Watson and Crick served as paradigms in their respective fields. Semiotics, the field of textual analysis as developed by Barthes in Writing Degree Zero, offered a new direction in the structuring of narrative whereby each distinct unit in a story formed a “code” or “isotopy” that categorizes the formal elements of the story. The historical concurrence of the discovery of the double helix and the publication of Writing Degree Zero may be mere coincidence, but this essay is an exploration of the intellectual influence that both events may have had on each other, since both the discovery of the double helix and Barthes’ publication gave expression to the new forms of knowledge 1 Françoise Dosse, History of Structuralism: The Rising Sign, 1945-1966, trans. -

James Watson and Francis Crick

James Watson and Francis Crick https://www.ducksters.com/biography/scientists/watson_and_crick.php biographyjameswatsonandfranciscrick.mp3 Occupation: Molecular biologists Born: Crick: June 8, 1916 Watson: April 6, 1928 Died: Crick: July 28, 2004 Watson: Still alive Best known for: Discovering the structure of DNA Biography: James Watson James Watson was born on April 6, 1928 in Chicago, Illinois. He was a very intelligent child. He graduated high school early and attended the University of Chicago at the age of fifteen. James loved birds and initially studied ornithology (the study of birds) at college. He later changed his specialty to genetics. In 1950, at the age of 22, Watson received his PhD in zoology from the University of Indiana. James Watson and Francis Crick https://www.ducksters.com/biography/scientists/watson_and_crick.php James D. Watson. Source: National Institutes of Health In 1951, Watson went to Cambridge, England to work in the Cavendish Laboratory in order to study the structure of DNA. There he met another scientist named Francis Crick. Watson and Crick found they had the same interests. They began working together. In 1953 they published the structure of the DNA molecule. This discovery became one of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century. Watson (along with Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962 for the discovery of the DNA structure. He continued his research into genetics writing several textbooks as well as the bestselling book The Double Helix which chronicled the famous discovery. Watson later served as director of the Cold Spring Harbor Lab in New York where he led groundbreaking research into cancer. -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr. -

April 28 Sir Paul Nurse

MONDAY, APRIL 26th 8 pm We look forward to welcoming to Kenton SIR PAUL NURSE RATHER THAN GIVE A TALK, WE ARE VERY FORTUNATE IN THAT SIR PAUL IS HAPPY TO ANSWER QUESTIONS ON HIS EXTENSIVE CAREER AND HOBBIES PLEASE HAVE YOUR QUESTIONS READY OR SEND THEM IN BEFORE THE MEETING Paul Nurse is a geneticist and cell biologist who has worked on how the eukaryotic cell cycle is controlled. His major work has been on the cyclin dependent protein kinases and how they regulate cell reproduction. He is Director of the Francis Crick Institute in London, and has served as President of the Royal Society, Chief Executive of Cancer Research UK and President of Rockefeller University. He shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and has received the Albert Lasker Award, the Gairdner Award, the Louis Jeantet Prize and the Royal Society's Royal and Copley Medals. He was knighted by The Queen in 1999, received the Legion d'honneur in 2003 from France, and the Order of the Rising Sun in 2018 from Japan. He served for 15 years on the Council of Science and Technology, advising the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and is presently a Chief Scientific Advisor for the European Union. As well as his many medical accomplishments, amazingly Paul also has time to fly planes and engage in varied hobbies Paul flies gliders and vintage aeroplanes and has been a qualified bush pilot. He also likes the theatre, hill-walking, going to museums and art galleries, and running very slowly. All our Zoom sessions are available on the Kenton https://us02web.zoom.us/j/3531782577? YouTube channel: pwd=N0tlSWxxUGZmOEUrM1ZzclJFN1pzdz09 Kenton Shul In The Park Goes Live.