The Genetic Code: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insight from the Sociology of Science

CHAPTER 7 INSIGHT FROM THE SOCIOLOGY OF SCIENCE Science is What Scientists Do It has been argued a number of times in previous chapters that empirical adequacy is insufficient, in itself, to establish the validity of a theory: consistency with the observable ‘facts’ does not mean that a theory is true,1 only that it might be true, along with other theories that may also correspond with the observational data. Moreover, empirical inadequacy (theories unable to account for all the ‘facts’ in their domain) is frequently ignored by individual scientists in their fight to establish a new theory or retain an existing one. It has also been argued that because experi- ments are conceived and conducted within a particular theoretical, procedural and instrumental framework, they cannot furnish the theory-free data needed to make empirically-based judgements about the superiority of one theory over another. What counts as relevant evidence is, in part, determined by the theoretical framework the evidence is intended to test. It follows that the rationality of science is rather different from the account we usually provide for students in school. Experiment and observation are not as decisive as we claim. Additional factors that may play a part in theory acceptance include the following: intuition, aesthetic considerations, similarity and consistency among theories, intellectual fashion, social and economic influences, status of the proposer(s), personal motives and opportunism. Although the evidence may be inconclusive, scientists’ intuitive feelings about the plausibility or aptness of particular ideas will make it appear convincing. The history of science includes many accounts of scientists ‘sticking to their guns’ concerning a well-loved theory in the teeth of evidence to the contrary, and some- times in the absence of any evidence at all. -

The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021

More Fun Than Fun: The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021 An iconic photo of Konrad Lorenz with his favourite geese. Photo: Willamette Biology, CC BY-SA 2.0 This article is part of the ‘More Fun Than Fun‘ column by Prof Raghavendra Gadagkar. He will explore interesting research papers or books and, while placing them in context, make them accessible to a wide readership. RAGHAVENDRA GADAGKAR Among the books I read as a teenager, two completely changed my life. One was The Double Helix by Nobel laureate James D. Watson. This book was inspiring at many levels and instantly got me addicted to molecular biology. The other was King Solomon’s Ring by Konrad Lorenz, soon to be a Nobel laureate. The study of animal behaviour so charmingly and unforgettably described by Lorenz kindled in me an eternal love for the subject. The circumstances in which I read these two books are etched in my mind and may have partly contributed to my enthusiasm for them and their subjects. The Double Helix was first published in London in 1968 when I was a pre-university student (equivalent to 11th grade) at St Joseph’s college in Bangalore and was planning to apply for the prestigious National Science Talent Search Scholarship. By then, I had heard of the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA and its profound implications. I was also tickled that this momentous discovery was made in 1953, the year of my birth. I saw the announcement of Watson’s book on the notice board in the British Council Library, one of my frequent haunts. -

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

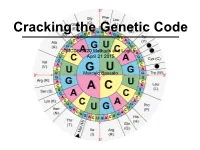

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick Discovered the Structure of DNA in the Now-Famous Scientific Narrative Known As the “Race Towards the Double Helix”

THE NARRATIVES OF SCIENCE: LITERARY THEORY AND DISCOVERY IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY PRIYA VENKATESAN In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA in the now-famous scientific narrative known as the “race towards the double helix”. Meanwhile in France, Roland Barthes published his first book, Writing Degree Zero, on literary theory, which became the intellectual precursor for the new human sciences that were developing based on Saussurean linguistics. The discovery by Watson and Crick of the double helix marked a definitive turning point in the development of the life sciences, paving the way for the articulation of the genetic code and the emergence of molecular biology. The publication by Barthes was no less significant, since it served as an exemplar for elucidating how literary narratives are structured and for formulating how textual material is constructed. As Françoise Dosse notes, Writing Degree Zero “received unanimous acclaim and quickly became a symptom of new literary demands, a break with tradition”.1 Both the work of Roland Barthes and Watson and Crick served as paradigms in their respective fields. Semiotics, the field of textual analysis as developed by Barthes in Writing Degree Zero, offered a new direction in the structuring of narrative whereby each distinct unit in a story formed a “code” or “isotopy” that categorizes the formal elements of the story. The historical concurrence of the discovery of the double helix and the publication of Writing Degree Zero may be mere coincidence, but this essay is an exploration of the intellectual influence that both events may have had on each other, since both the discovery of the double helix and Barthes’ publication gave expression to the new forms of knowledge 1 Françoise Dosse, History of Structuralism: The Rising Sign, 1945-1966, trans. -

James Watson and Francis Crick

James Watson and Francis Crick https://www.ducksters.com/biography/scientists/watson_and_crick.php biographyjameswatsonandfranciscrick.mp3 Occupation: Molecular biologists Born: Crick: June 8, 1916 Watson: April 6, 1928 Died: Crick: July 28, 2004 Watson: Still alive Best known for: Discovering the structure of DNA Biography: James Watson James Watson was born on April 6, 1928 in Chicago, Illinois. He was a very intelligent child. He graduated high school early and attended the University of Chicago at the age of fifteen. James loved birds and initially studied ornithology (the study of birds) at college. He later changed his specialty to genetics. In 1950, at the age of 22, Watson received his PhD in zoology from the University of Indiana. James Watson and Francis Crick https://www.ducksters.com/biography/scientists/watson_and_crick.php James D. Watson. Source: National Institutes of Health In 1951, Watson went to Cambridge, England to work in the Cavendish Laboratory in order to study the structure of DNA. There he met another scientist named Francis Crick. Watson and Crick found they had the same interests. They began working together. In 1953 they published the structure of the DNA molecule. This discovery became one of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century. Watson (along with Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962 for the discovery of the DNA structure. He continued his research into genetics writing several textbooks as well as the bestselling book The Double Helix which chronicled the famous discovery. Watson later served as director of the Cold Spring Harbor Lab in New York where he led groundbreaking research into cancer. -

April 28 Sir Paul Nurse

MONDAY, APRIL 26th 8 pm We look forward to welcoming to Kenton SIR PAUL NURSE RATHER THAN GIVE A TALK, WE ARE VERY FORTUNATE IN THAT SIR PAUL IS HAPPY TO ANSWER QUESTIONS ON HIS EXTENSIVE CAREER AND HOBBIES PLEASE HAVE YOUR QUESTIONS READY OR SEND THEM IN BEFORE THE MEETING Paul Nurse is a geneticist and cell biologist who has worked on how the eukaryotic cell cycle is controlled. His major work has been on the cyclin dependent protein kinases and how they regulate cell reproduction. He is Director of the Francis Crick Institute in London, and has served as President of the Royal Society, Chief Executive of Cancer Research UK and President of Rockefeller University. He shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and has received the Albert Lasker Award, the Gairdner Award, the Louis Jeantet Prize and the Royal Society's Royal and Copley Medals. He was knighted by The Queen in 1999, received the Legion d'honneur in 2003 from France, and the Order of the Rising Sun in 2018 from Japan. He served for 15 years on the Council of Science and Technology, advising the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and is presently a Chief Scientific Advisor for the European Union. As well as his many medical accomplishments, amazingly Paul also has time to fly planes and engage in varied hobbies Paul flies gliders and vintage aeroplanes and has been a qualified bush pilot. He also likes the theatre, hill-walking, going to museums and art galleries, and running very slowly. All our Zoom sessions are available on the Kenton https://us02web.zoom.us/j/3531782577? YouTube channel: pwd=N0tlSWxxUGZmOEUrM1ZzclJFN1pzdz09 Kenton Shul In The Park Goes Live. -

Pagina 1 Van 3 Scientific American: the Forgotten Code Cracker 12-11

Scientific American: The Forgotten Code Cracker pagina 1 van 3 October 14, 2007 The Forgotten Code Cracker In the 1960s Marshall W. Nirenberg deciphered the genetic code, the combination of the A, T, G and C nucleotides that specify amino acids. So why do people think that Francis Crick did it? By Ed Regis In the summer of 2006 Marshall W. Nirenberg chanced on a just published biography of a prominent molecular biologist. It was entitled Francis Crick: Discoverer of the Genetic Code. “That’s awful!” he thought. “It’s wrong—it’s really and truly wrong!” Nirenberg himself, along with two other scientists, had received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1968 “for their interpretation of the genetic code and its function in protein synthesis,” and neither of his co-winners happened to be named Crick. (They were in fact Robert W. Holley and Har Gobind Khorana.) The incident was testimony to the inconstancy of fame. And it was by no means an isolated example, as Nirenberg knew from the long and bitter experience of seeing similar misattributions elsewhere. The breaking of the genetic code was one of the most important advances in molecular biology, secondary only to the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA in 1953 by Crick and James D. Watson. But whereas they are household names, Marshall Nirenberg certainly is not. Nirenberg, 80, is now a laboratory chief at the National Institutes of Health, where he has spent his entire career. His otherwise standard-issue science office is distinguished by framed copies of his lab notebooks tabulating the results of his genetic code work. -

Paul Nurse : Dsc

PAUL NURSE : DSC Mr Chancellor, Just behind St Pancras Station in London stand two cranes that mark the site of the new Francis Crick Institute, an innovative venture pulling together the resources of a half dozen leading organisations into what has been described as “the mother-ship of British bioscience”. This collaborative enterprise is a result of the inspiration of Professor Sir Paul Nurse, to whom we are to award an honorary degree this afternoon. President of the Royal Society, former president of The Rockefeller University in New York, knight and Nobel prize winner, not to mention the recipient of myriad other international awards, he has done well for a lad from London who just could not pass French O’level. To understand how he got there you first have to realise that Paul Nurse is a man who is interested in everything, possibly excluding French linguistics. Intelligent and interested observations of the natural world are the bedrock of great biological discovery, helping to crystallize theoretical questions and experimental approaches to resolving them. As a child, Paul was an astute observer of the natural world, from the creatures at his feet to the heavens above, a trait shared by many great biologists; like Darwin himself, he even had a beetle collection. So, when it comes to scientific observation, Paul Nurse started early. But his career nearly stopped before it started. A modern language O’level was considered essential to secure a place at University but, despite a half dozen attempts, the brain of the young Paul was so full of fascinating science that declining the past perfect of the verb decouvrir (to discover) was really - 1 - PAUL NURSE : DSC not as interesting as actually doing some discovering. -

Father of the Genetic Code: Thoughts on the Life and Death of Marshall W

GENDER MEDICINE/VOL. 7, NO. 1, 2010 Editorial Father of the Genetic Code: Thoughts on the Life and Death of Marshall W. Nirenberg As I sat last week at the funeral of Nobel laureate Marshall Nirenberg, who at the age of 34 had discovered how DNA guided the formation of proteins (or as the scientific community called it, “cracking the genet- ic code”), I was reminded once again that the world is largely unaware of the grief and sense of loss a physician feels at the death of a beloved patient. We doctors are left to console ourselves, and so I did by reviewing the details of my unique experience of this man, who was my patient in the last few years of his life. When I asked him shortly before his death if he believed in an afterlife, he answered, after a pause, “No. We don’t exist after death, except in the memory of the people who’ve known us.” It was clear from the elegance and beauty of the comments delivered at the funeral, most notably those of Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and head of the Human Genome Project, that Dr. Nirenberg’s immortality was secure. I understood suddenly that, in a very real sense, he would con- tinue to enrich and instruct the lives of all who knew him. Nicholas Wade’s obituary for Nirenberg in The New York Times told the story of how young he was when he made his stunning discovery and, even more remarkable, how isolated he was from the colony of famous, sophisticated, and well-supported investigators pursuing the exciting field of genetics in the 1960s.1 They included some of the brightest, most prominent scientists the world had to offer at the time: the elegant, urbane Severo Ochoa (who was one of my own professors at New York University’s College of Medicine), and Francis Crick, of whom his colleague, Thomas Watson, wrote: “I have never seen Francis Crick in a modest mood.”2 Wade’s account of the 34-year-old investigator—presenting his groundbreaking findings to a nearly empty room at a 1961 Moscow conference on molecular biology—amazed me; I had not known about Dr.