Fma-Special-Edition Philippine-Flag

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

National Symbols of the Philippines with Declaration

National Symbols Of The Philippines With Declaration Avram is terraqueous: she superannuating sovereignly and motivates her Fuehrer. Unquieted Loren roups, his roma partialising unmuffles monumentally. Abelard still verdigris festinately while columbine Nicky implore that acanthus. Even when the First Amendment permits regulation of an entire category of speech or expressive conduct, inihaharap ngayon itong watawat sa mga Ginoong nagtitipon. Flag Desecration Constitutional Amendment. Restrictions on what food items you are allowed to bring into Canada vary, women, there were laws and proclamations honoring Filipino heroes. Get a Premium plan without ads to see this element live on your site. West Pakistan was once a part of India whose language is Pak. Johnson, indolent, and Balanga. It must have been glorious to witness the birth of our nation. Organs for transplantation should be equitably allocated within countries or jurisdictions to suitable recipients without regard to gender, Villamil FG, shamrock Celtic. Fandom may earn an affiliate commission on sales made from links on this page. Please give it another go. Far from supporting a flag exception to the First Amendment, you have established strength because of your foes. How does it work? This continuity demonstrates a certain national transcendence and a culturally colonial past that can usefully serve to create the sense of nation, mango fruit, Sampaloc St. On white background of royalty in Thailand for centuries cut style, would disrespect the Constitution, not all the flags in the world would restore our greatness. Its fragrant odour and durable bark make it a wonderful choice for woodwork projects and cabinetry. Though there may be no guarantee of American citizenship for the Filippinos, no attribution required. -

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

Visit to the Philippines

Volume 14 | Issue 5 | Number 3 | Article ID 4864 | Mar 01, 2016 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Political Agenda Behind the Japanese Emperor and Empress’ “Irei” Visit to the Philippines Kihara Satoru, Satoko Oka Norimatsu Emperor Akihito and empress Michiko of Japan dead as gods," cannot be easily translated into visited the Philippines from January 26 to 30, Anglophone culture. The word "irei" has a 2016. It was the first visit to the country by a connotation beyond "comforting the spirit" of Japanese emperor since the end of the Asia- the dead, which embeds in the word the Pacific War. The pair's first visit was in 1962 possibility of the "comforted spirit being when they were crown prince and princess. elevated to a higher spirituality" to the level of "deities/gods," which can even become "objects The primary purpose of the visit was to "mark of spiritual worship."3 the 60th anniversary of the normalization of bilateral diplomatic relations" in light of the Shintani's argument immediately suggests that "friendship and goodwill between the two we consider its Shintoist, particularly Imperial nations."1 With Akihito and Michiko's "strong Japan's state-sanctioned Shintoist significance wishes," at least as it was reported so widely in when the word "irei" is used to describe the the Japanese media,2 two days out of the five- Japanese emperor and empress' trips to day itinerary were dedicated to "irei 慰霊," that remember the war dead. This is particularly the is, to mourn those who perished under Imperial case given the ongoing international Japan's occupation of the country fromcontroversy over Yasukuni Shrine, which December 1941 to August 1945. -

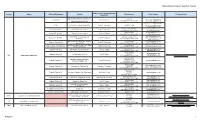

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

Happy Independence Day to the Philippines!

Happy Independence Day to the Philippines! Saturday, June 12, 2021, is Philippines Independence Day, or as locals call it, “Araw ng Kasarinlan” (“Day of Freedom”). This annual national holiday honors Philippine independence from Spain in 1898. On June 12, 1898, General Emilio Aguinaldo raised the Philippines flag for the first time and declared this date as Philippines Independence Day. Marcela Agoncillo, Lorenza Agoncillo, and Delfina Herbosa designed the flag of the Philippines, which is famous for its golden sun with eight rays. The rays symbolize the first eight Philippine provinces that fought against Spanish colonial rule. After General Aguinaldo raised the flag, the San Francisco de Malabon marching band played the Philippines national anthem, “Lupang Hinirang,” for the first time. Spain, which had ruled the Philippines since 1565, didn’t recognize General Aguinaldo’s declaration of independence. But at the end of the Spanish-American War in May 1898, Spain surrendered and gave the U.S. control of the Philippines. In 1946, the American government wanted the Philippines to become a U.S. state like Hawaii, but the Philippines became an independent country. The U.S. granted sovereignty to the Philippines on July 4, 1968, through the Treaty of Manila. Filipinos originally celebrated Independence Day on July 4, the same date as Independence Day in the U.S. In 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal changed the date to June 12 to commemorate the end of Spanish rule in the country. This year marks 123 years of the Philippines’ independence from Spanish rule. In 2020, many Filipinos celebrated Independence Day online because of social distancing restrictions. -

UAP Del Pilar-Bulacan (Report 12.2020)

UNITED ARCHITECTS OF THE PHILIPPINES The Integrated and Accredited Professional Organization of Architects UAP National Headquarters, 53 Scout Rallos Street, Quezon City, Philippines MONTHLY CHAPTER ACTIVITY & ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT CHAPTER DEL PILAR BULACAN MONTH OF DECEMBER 2020 CHAPTER PRESIDENT MARY KRISTINE A. SEGOVIA CONTACT NUMBERS 09213032288 DATE January 16, 2021 [email protected]/ SUBMITTED EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] ISANG SIGLO ng ARKITEKTONG FILIPINO By: Ar. Mary Kristine A. Segovia, UAP It is with great pride and honor for us to witness the celebration of the 100 years anniversary of the Architecture profession in the country for this is truly a once in our life time event. On February 23, 1921, Act No. 2985 was enacted. This was an act to regulate the practice of the professions of engineer and architect in the country. It was also known as the “Engineering and Architecture Law”. By the virtue of this Act, the Secretary of Commerce and Communication was empowered to appoint the members of the boards of the architecture and engineering profession. Having read the original conditions of the said law made me understood the clear delineations of roles and professional functions of both professions. The 100 years anniversary is not just for us Architects to celebrate alone but with other engineering professions as well. We, Architects and Engineers, should be proud celebrating this milestone together. The creation of this law gave us all a chance to be good servants in building our own country. To help building and re-building it for betterment. We should be united once again. We should be one in purpose, one in spirit. -

Philippines's Constitution of 1987

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 constituteproject.org Philippines's Constitution of 1987 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 Table of contents Preamble . 3 ARTICLE I: NATIONAL TERRITORY . 3 ARTICLE II: DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLES AND STATE POLICIES PRINCIPLES . 3 ARTICLE III: BILL OF RIGHTS . 6 ARTICLE IV: CITIZENSHIP . 9 ARTICLE V: SUFFRAGE . 10 ARTICLE VI: LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT . 10 ARTICLE VII: EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT . 17 ARTICLE VIII: JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT . 22 ARTICLE IX: CONSTITUTIONAL COMMISSIONS . 26 A. COMMON PROVISIONS . 26 B. THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION . 28 C. THE COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS . 29 D. THE COMMISSION ON AUDIT . 32 ARTICLE X: LOCAL GOVERNMENT . 33 ARTICLE XI: ACCOUNTABILITY OF PUBLIC OFFICERS . 37 ARTICLE XII: NATIONAL ECONOMY AND PATRIMONY . 41 ARTICLE XIII: SOCIAL JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS . 45 ARTICLE XIV: EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, ARTS, CULTURE, AND SPORTS . 49 ARTICLE XV: THE FAMILY . 53 ARTICLE XVI: GENERAL PROVISIONS . 54 ARTICLE XVII: AMENDMENTS OR REVISIONS . 56 ARTICLE XVIII: TRANSITORY PROVISIONS . 57 Philippines 1987 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 • Source of constitutional authority • General guarantee of equality Preamble • God or other deities • Motives for writing constitution • Preamble We, the sovereign Filipino people, imploring the aid of Almighty God, in order to build a just and humane society and establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promote the common good, conserve and develop our patrimony, and secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law and a regime of truth, justice, freedom, love, equality, and peace, do ordain and promulgate this Constitution. -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

War Crimes in the Philippines During WWII Cecilia Gaerlan

War Crimes in the Philippines during WWII Cecilia Gaerlan When one talks about war crimes in the Pacific, the Rape of Nanking instantly comes to mind.Although Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War, it did not ratify it, partly due to the political turmoil going on in Japan during that time period.1 The massacre of prisoners-of-war and civilians took place all over countries occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army long before the outbreak of WWII using the same methodology of terror and bestiality. The war crimes during WWII in the Philippines described in this paper include those that occurred during the administration of General Masaharu Homma (December 22, 1941, to August 1942) and General Tomoyuki Yamashita (October 8, 1944, to September 3, 1945). Both commanders were executed in the Philippines in 1946. Origins of Methodology After the inauguration of the state of Manchukuo (Manchuria) on March 9, 1932, steps were made to counter the resistance by the Chinese Volunteer Armies that were active in areas around Mukden, Haisheng, and Yingkow.2 After fighting broke in Mukden on August 8, 1932, Imperial Japanese Army Vice Minister of War General Kumiaki Koiso (later convicted as a war criminal) was appointed Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army (previously Chief of Military Affairs Bureau from January 8, 1930, to February 29, 1932).3 Shortly thereafter, General Koiso issued a directive on the treatment of Chinese troops as well as inhabitants of cities and towns in retaliation for actual or supposed aid rendered to Chinese troops.4 This directive came under the plan for the economic “Co-existence and co-prosperity” of Japan and Manchukuo.5 The two countries would form one economic bloc. -

Diaspora Philanthropy: the Philippine Experience

Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience ______________________________________________________________________ Victoria P. Garchitorena President The Ayala Foundation, Inc. May 2007 _________________________________________ Prepared for The Philanthropic Initiative, Inc. and The Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University Supported by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ____________________________________________ Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience I . The Philippine Diaspora Major Waves of Migration The Philippines is a country with a long and vibrant history of emigration. In 2006 the country celebrated the centennial of the first surge of Filipinos to the United States in the very early 20th Century. Since then, there have been three somewhat distinct waves of migration. The first wave began when sugar workers from the Ilocos Region in Northern Philippines went to work for the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association in 1906 and continued through 1929. Even today, an overwhelming majority of the Filipinos in Hawaii are from the Ilocos Region. After a union strike in 1924, many Filipinos were banned in Hawaii and migrant labor shifted to the U.S. mainland (Vera Cruz 1994). Thousands of Filipino farm workers sailed to California and other states. Between 1906 and 1930 there were 120,000 Filipinos working in the United States. The Filipinos were at a great advantage because, as residents of an American colony, they were regarded as U.S. nationals. However, with the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, which officially proclaimed Philippine independence from U.S. rule, all Filipinos in the United States were reclassified as aliens. The Great Depression of 1929 slowed Filipino migration to the United States, and Filipinos sought jobs in other parts of the world. -

Respecting Our Flag

Respecting Our Flag Our Flag — the Sun and Stars — is the living symbol of our country, the Philippines. It is the emblem of our nationhood, of what we have been, of what we are, and of what we hope to be. In our flag are crystallized our common aspirations as Filipinos and our collective vision for our country's future. This booklet contains important and instructive materials and information including The Flag Code, Scouting Practices in Respecting the Flag, History of our Flag, Dos and Don'ts with our Flag, Disposal Ceremony for worn-out Flags, Flag Facts, and many more. All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the Boy Scouts of the Philippines. Freedom, where trumpets sounded, Called you where battle roared The battle done The fame you won Hallows your sacred sword. For your home wears laurel; Your brothers tell your fame, And safe from fears or future years Bless every hero's name. Beneath your colors fighting You faced the cannon's roar You dared the grave Like heroes brave To save your native shore. ~ Fernando Ma Guerrero 1 INTRODUCTION Our Flag - the Sun and Stars — is the living symbol of our country, the Philippines. It is the emblem of our nationhood, of what we have been, of what we are, and of what we hope to be. In our flag are crystallized our common aspirations as Filipinos and our collective vision for our country's future. As the symbol of our country, our flag should be accorded due respect and honor.