Norton: the Collected Writings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transfigurations of Caroline Norton Author(S): Kieran Dolin Source: Victorian Literature and Culture, Vol

The Transfigurations of Caroline Norton Author(s): Kieran Dolin Source: Victorian Literature and Culture, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2002), pp. 503-527 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25058602 Accessed: 18/02/2010 00:19 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Victorian Literature and Culture. http://www.jstor.org Victorian Literature and Culture (2002), 503-527. Printed in the United States of America. Copyright ? 2002 Cambridge University Press. -

Marketing “Proper” Names: Female Authors, Sensation

MARKETING “PROPER” NAMES: FEMALE AUTHORS, SENSATION DISCOURSE, AND THE MID-VICTORIAN LITERARY PROFESSION By Heather Freeman Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English August, 2013 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Carolyn Dever Jay Clayton Rachel Teukolsky James Epstein Copyright © 2013 by Heather Freeman All Rights Reserved For Sean, with gratitude for your love and unrelenting support iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the influence, patience, and feedback of a number of people, but I owe a particular debt to my committee, Professors Carolyn Dever, Jay Clayton, Rachel Teukolsky, and Jim Epstein. Their insightful questions and comments not only strengthened this project but also influenced my development as a writer and a critic over the last five years. As scholars and teachers, they taught me how to be engaged and passionate in the archive and in the classroom as well. My debt to Carolyn Dever, who graciously acted as my Director, is, if anything, compound. I cannot fully express my gratitude for her warmth, patience, incisive criticism, and unceasing willingness to read drafts, even when she didn’t really have the time. The administrative women of the English Department provided extraordinary but crucial support and encouragement throughout my career at Vanderbilt. Particular thanks go to Janis May and Sara Corbitt, and to Donna Caplan, who has provided a friendly advice, a listening ear, and much-needed perspective since the beginning. I also owe a great deal of thanks to my colleagues in the graduate program at Vanderbilt. -

The Life of the Honourable Mrs. Norton

I MBi MiUJPJMii THE LIFE OF MF PERKINS LIBRARY OF THE University of California. Class r^ J UHl^5 , '""> O/ ^ V O^sUOTAtcrit^ e J THE LIFE OF THE HONOURABLE MRS. NORTON BY JANE GRAY PERKINS WITH PORTRAITS ^ OF UNiVF NEW YORK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY 1909 ; M5 P4 NOTE For the materials which make the foundation of this biography my thanks are due first to members of Mrs. Norton's own family—her grandson, Lord Grantley, whose permission made it possible for me to use her letters, both those already published and those which appear for the first time in these pages her granddaughter, the Hon. Carlotta Norton ; her niece, Lady Guendolen Ramsden ; and Mrs. Sheridan of Frampton Court; whose personal recollections of Mrs. Norton and kind hospitality in letting me see certain scrap-books and MSS. and family pictures have greatly aided me in my work. I must also thank the directors of the Library in the British Museum for their courtesy in allowing me the privileges of this invaluable collection, at a time when the condition of the building, while undergoing repairs, might have furnished adequate excuse for denying those privileges to the passing stranger certainly, if not to the regular reader. I wish also to express my obligations to Mr. Murray, who kindly allowed me to use several hitherto unpub- lished letters from Mrs. Norton to his grandfather written between the years 1834-8. For the great mass of my material, however, I find it difficult to make any adequate acknowledgment, so rich and so varied is the treasure which English 194223 vi NOTE writers of biography and letters have expended upon the period and personages especially included in this biography. -

Transformations of Sappho: Late 18Th Century to 1900

Transformations of Sappho Late 18th Century to 1900 Athulya Aravind English Department Advisor: Guy Rotella Honors Junior/Senior Process, 2011 2 CONTENTS I – Introduction 3 II – Male Romantic Poets 11 III – Nineteenth Century Women Poets 34 IV - Victorian Male Poets 61 V – Michael Field 87 VI – Conclusion 99 Works Cited 101 3 I – Introduction The poet Sappho, a major exemplar of lyric verse and famous as the first female poet in Western literary history, is believed to have lived on the Greek island of Lesbos sometime in the 6th century BCE. So great was Sappho‘s fame in the ancient world that some six hundred years after her death, her lyrics were gathered into nine books organized in metrical schemes, subjects, performance styles, and genres. But, these books and most other records of Sappho disappeared in around the 9th century CE, and both Sappho and her works were largely repressed or neglected—for reasons both moral and accidental—during the Middle Ages. Happily, however, a small portion of Sappho‘s verse was rediscovered during the Renaissance, as an aspect of that period‘s more general revival of classical art and learning. Since then, the available corpus of Sappho‘s work has grown somewhat, especially with the resurfacing of several significant poetic fragments in the 19th and 20th centuries. Despite these recoveries, however, our archive of the poet‘s work remains extremely small: a single full poem (the ―Ode to Aprhodite,‖ known as Fragment 1). One fairly long poem (―He seems to me equal to a god,‖ known as Fragment 31), and several small, sometimes tiny scraps, many of them only a line or two long. -

Mary Julia Young She Applied to the Royal Literary Fund for Help Until She Could Complete Her Next Work

Mary Julia Young she applied to the Royal Literary Fund for help until she could complete her next work. MAJOR WORKS : The Family Party; A Comic Piece, in Two Acts (London, 1789) ; Adelaide and Antonine; or, the Emigrants: A Tale (London, 1793); Genius and Fancy; or, Dramatic Sketches: With Other Poems on Various Subjects (London, 1795); Poems (London, 1798), reprinted in The Metrical Museum. Part I. Containing, Agnes; or, the Wanderer, a Story Founded on the French Revolution. The Flood, an Irish Tale. Adelaide and Antonine; or, The Emigrants. With Other Original Poems (London, [1801]); The East Indian, or Clijford Priory, 4 vols. (London, 1799; reprint, Dublin, 1800); Moss Clijf Abbey; or, The Sepulchral Har monist, a Mysterious Tale, 4 vols. (London, 1803); Right and Wrong; or, The Kinsmen of Naples, A Romantic Story, 4 vols. (London, 1803); Donalda; or, The Witches ef Glenshiel, 2 vols. (London, 1805); Memoirs ef Mrs. Crouch; Including a Retrospect ef the Stage during the Years she Performed, 2 vols. (London, 1806); Rose Mount Castle, or False Reports, 3 vols. (London, bef. l8ro); A Summer at Brighton, or The Resort of Fashion, 3 vols. (London, bef. 18ro); A Summer at Weymouth, or the Star ef Fashion, 3 vols. (London, bef. 18ro); The Heir ef Drumcondra; or, Family Pride, 3 vols. (London, 1810). TRANSLATIONS : The Mother and Daughter, a Pathetic Tale, from the French of Berthier; 3 vols. (London, 1804); Francois Maria Arouet de Voltaire, Voltariana, 4 vols. (London, 1805); Lindorf and Caroline, from the German of Prof. Cramer, 3 vols. (n.p., n.d.) . TEXTS USED : Texts of "An Ode to Fancy," "Sonnet to Dreams," and "To Miss -- on Her Spending Too Much Time at Her Looking Glass" from Genius and Fancy; or, Dramatic Sketches: with Other Poems on Various Subjects (1795). -

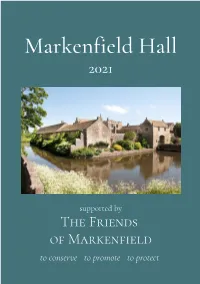

The Hall's Heroine Caroline Norton May No Longer Be the Household-Name She Once Was, but We Hope That This Will Be the Year to Change That

Markenfield Hall 2021 supported by The Friends of Markenfield to conserve to promote to protect Welcome to Markenfield Hall “It is an extraordinary privilege to live in one of the most unspoiled surviving early fourteenth-century houses in England, and seemingly one of the most continuously inhabited since that time. It is a place with an astonishing history, beginning with its entry in the Domesday Book (1086) and continuing to the present day, sometimes peacefully, sometimes in considerable strife. It is now being gradually restored to something of the status and dignity for which it was built. Whilst Markenfield has had its fair share of unhappiness over the centuries, it has a remarkable atmosphere: peaceful and benign. Visitors often remark on that, and we hope, when you can visit, that you take away some of that peace with you.” Mr Ian & Lady Deirdre Curteis cover image by kind permission of Tim Hardy image on the right by kind permission of Val Corbett A medieval, moated and much-loved family home, Markenfield Hall is a historic house unlike any other. Set within stunning Yorkshire countryside south of Ripon, medieval Markenfield has remained largely untouched, and is one of a handful of moated manor houses that could still be recognised by their original owners; indeed the Hall is instantly recognisable thanks to its crenelated silhouette reflected in its encircling moat, which was patrolled by two Black Swans until 2019 - when we discovered we had acquired an Otter… seven hundred years You will find that things have changed somewhat this year: Open Days have morphed into Tiny Tours, Lectures are Online and group sizes will be smaller. -

Caroline'norton

Caroline'Norton (1808-1877) Caroline Elizabeth Sarah Sheridan Norton, one of seven children of Thomas and Caroline Henrietta Callander Sheridan, from the beginning seemed des tined for fame. Richard Brimley Sheridan was her paternal grandfather; her paternal grandmother was the soprano Elizabeth Linley; and her mother was the author of Aims and Ends, Carwell, and other novels well known in their time. Today she is best known as a political reformer who played a pivotal role in influencing the passage through Parliament of the Infants' Custody Bill (1839) and the Marriage and Divorce Act of 1857. But Norton was known in her own time not only as the author of important political pamphlets but as a poet, a fiction writer, an essayist, an editor, and a fashionable celebrity at the center of a major political scandal. Caroline Norton was born in London on 22 March 1808, a year before her family lost its fortune in the Drury Lane Theatre fire. When she was only five, she and several of her siblings were sent to Scotland to live with her mother's family. Her parents went to live at the Cape of Good Hope for the health of her father, who was seriously ill, and so that he could assume the position of colonial secretary. When he died in 1817, her mother's fiction writing became the family's major source of income. Even so, Norton grew up in privileged surroundings, for the duke of York gave her mother apart ments in Hampton Court Palace, and the family eventually moved to Great George Street, Westminster, for part of the year. -

The Three Graces”

PRESS RELEASE “THE THREE GRACES” A queen of beauty A feminist social reformer A literary talent Muncaster Castle celebrates the astonishing achievements of three remarkable Victorian women. For over 800 years, talented, plucky and spirited women are found peppered liberally throughout the family tree of Iona Frost-Pennington, the current owner. Thomas Sheridan and Caroline Henrietta Callander, had three daughters: Caroline, Helen and Jane Georgiana. Collectively these three sisters were known by their contemporaries, because of their beauty, wit and accomplishments, as “The Three Graces”. Georgiana is Iona’s great-great-great grandmother. The Honourable Caroline Norton & Her Sisters, William Etty c.1847 Image courtesy of Manchester Art Gallery. Installations transform the Castle rooms into an Exhibition showcasing the lives of the Sheridan Sisters with, costumes worn by Georgiana when she was Queen of Beauty at the Eglinton Tournament, songs and poems by Helen, and the determination of Caroline. Local dressmaker Celestina Mahović is stitching a replica of Georgiana’s Queen of Beauty dress for Iona’s daughter, Isla. The finishing touches will be made just in time for the Exhibition opening and, when not being modelled by Georgiana’s 4x great granddaughter, will be on display in the Castle. Georgiana was crowned the Eglinton Beauty at the renowned Scottish Eglinton Tournament in 1839. “No lady throughout the empire could have been chosen whose preeminent attractors of face and figure, whose elegance of manners, whose correctness of taste and feminine dignity and demeanour could better have entitled her to have the proud rank of the ‘Queen of Beauty’” Work in Progress: Fleur De (Commentators of 1839) Lis, will embellish Isla’s dress. -

A Rediscovered Life: a Selective Annotated Edition of the Letters of Caroline Elizabeth Norton, 1828–1877

A REDISCOVERED LIFE: A SELECTIVE ANNOTATED EDITION OF THE LETTERS OF CAROLINE ELIZABETH NORTON, 1828–1877 ROSS BELSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Cultural Industries, University of the West of England, Bristol July 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis is a selective and annotated edition of 157 of the 2200 extant letters by Caroline Elizabeth Norton currently known to be available in both the public and private domain, which have been collected and transcribed for the project. The selection includes both the first extant letter, dated 28 July [1828] and the last, written on 10 June 1877, five days before Caroline Norton’s death. Norton’s letters to Lord Melbourne already published in an annotated edition (see Bibliography) have not been included in the selection. The letters are grouped chronologically into five sections, each representing approximately a decade of the author’s life. Each section concludes a chapter of commentaries outlining the key historical and political events of each period and providing a thematic analysis of how the letters, including the residual 92% of correspondence not selected for the edition, comment on aspects of Caroline Norton’s life, beliefs, work, family, relationships and society. In particular, the discussion will focus on how the letters challenge existing notions in these areas and reflect on comparably under-investigated or almost entirely non-researched biographical topics, such as Norton’s views on literature and other writers, her health, and the nature of her relationships with her family, particularly her son Brinsley, and other key individuals in her life, such as Mary Shelley, Edward Trelawny, Lord Melbourne and Sidney Herbert. -

Anti- Conquest

Sherine Fouad Mazloum Title: Reading the ‘anti- conquest’: A Critique of Orientalist and Exoticist Representations in Lucie Duff Gordon’s Letters From Egypt Author: Sherine Fouad Mazloum Affiliation: Associate Professor of English Literature Department of English Language and Literature Faculty of Arts – Ain Shams University Cairo – Egypt Postal Address: 5 Al Sheikh Mohamed El Nady street, off Makram Ebeid, Nasr city, Cairo, Egypt – third floor – flat 6 Short Bio: Dr. Sherine Fouad Mazloum is an Associate Professor of English Literature at the Faculty of Arts, Ain Shams University. Her PhD entitled A Double Vision: A Study of Disraeli’s Trilogy (20020 tackles Benjamin Disraeli’s trilogy from a postcolonial perspective while her MA entitled A Feminist Critique of Virginia Woolf (1996) engages with Woolf’s fictional and non-fictional works from a feminist perspective. Her research interests include areas of gender and postcolonial studies as well as British literature. She has published a number of publications tackling topics such as metonymy in Narayan’s fiction, cross genre study of identity formation in Elizabeth Bishop, Egyptian women novelists writing the revolution, displacement in British immigrant fiction, among others. x I (281) Reading the ‘anti- conquest’: A Critique of Orientalist and Exoticist Representations in Lucie Duff Gordon’s Letters From Egypt Abstract Reading the ‘anti- conquest’: A Critique of Orientalist and Exoticist Representations in Lucie Duff Gordon’s Letters From Egypt By Sherine Fouad Mazloum This paper aims to analyze Lucie Duff Gordon’s Letters from Egypt in light of Mary Louise Pratt’s coined term “anti-conquest” which refers to “the strategies of representation whereby the European subject secures his innocence while maintaining western hegemony” (7). -

Victorian Women and Wayward Reading by Marisa Knox a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of Th

Identification Crises: Victorian Women and Wayward Reading By Marisa Knox A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Professor Catherine Gallagher Professor Carla Hesse Spring 2013 1 Abstract Identification Crises: Victorian Women and Wayward Reading by Marisa Knox Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Ian Duncan, Chair In the Victorian period, no assumption about female reading generated more ambivalence and anxiety than the supposedly feminine facility for identifying with fictional characters and plots. Simultaneously, no assumption about women’s reading seemed to be more axiomatic. Conservatives and radicals, feminists and anti-feminists, artists and scientists, and novelists and critics throughout the long nineteenth century believed implicitly in women’s essential tendency to internalize textual perspectives to their detriment. My dissertation re-thinks the discourse of “crisis” over women’s literary identification in opposition to increasing representation of what I call “wayward reading,” in which women approached identification as a flexible capacity instead of an emotional compulsion. I argue that the constant anxiety expressed by Victorian writers about women’s absorption in literature helped to reify irrational and involuntary identification as the feminine norm, even while accounts of women’s elective reading response defied this narrative. This study analyzes and contextualizes three major types of deliberately wayward reading in the Victorian era, which challenge the premises of gendered identification that often obtain in criticism and pedagogy today. The first chapter explores the imaginative license granted to women readers, as opposed to women writers, to identify with male subjects. -

Nineteenth-Century British Child Law and Literature

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 Knowing Children/Children Knowing: Nineteenth-Century British Child Law and Literature Donna Paparella Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1085 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] KNOWING CHILDREN/CHILDREN KNOWING: NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH CHILD LAW AND LITERATURE by DONNA PAPARELLA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of English, The City University of New York 2015 Paparella ii © 2015 DONNA PAPARELLA All Rights Reserved Paparella iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Talia Schaffer ___________________ ______________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Mario DiGangi ___________________ ______________________ Date Executive Officer Talia Schaffer Rachel Brownstein Anne Humpherys Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Paparella iv Abstract KNOWING CHILDREN/CHILDREN KNOWING: NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH CHILD LAW AND LITERATURE by Donna Paparella Adviser: Professor Talia Schaffer