The Golden Age of Auto Racing Revisited Part II—1960 Through 1966 ©*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maserati 100 Años De Historia 100 Years of History

MUNDO FRevista oficialANGIO de la Fundación Juan Manuel Fangio MASERATI 100 AÑOS DE HISTORIA 100 YEARS OF HISTORY FANGIO LA CARRERA Y EL Destinos / Destination DEPORTISTA DEL SIGLO MODENA THE RACE AND THE Autos / Cars SPORTSMAN OF THE CENTURY MASERATI GRANCABRIO SPORT Entrevista / Interview Argentina $30 ERMANNO COZZA TESTORELLI 1887 TAG HEUER FORMULA 1 CALIBRE 16 Dot Baires Shopping By pushing you to the limit and breaking all boundaries, Formula 1 is more La Primera Boutique de TAG HEUER than just a physical challenge; it is a test of mental strength. Like TAG Heuer, en Latinoamérica you have to strive to be the best and never crack under pressure. TESTORELLI 1887 TAG HEUER FORMULA 1 CALIBRE 16 Dot Baires Shopping By pushing you to the limit and breaking all boundaries, Formula 1 is more La Primera Boutique de TAG HEUER than just a physical challenge; it is a test of mental strength. Like TAG Heuer, en Latinoamérica you have to strive to be the best and never crack under pressure. STAFF SUMARIO Dirección Editorial: Fundación Museo Juan Manuel Fangio. CONTENTS Edición general: Gastón Larripa 25 Editorial Redacción: Rodrigo González 6 Editorial Colaboran en este número: Daniela Hegua, Néstor Pionti, Laura González, Lorena Frances- Los autos Maserati que corrió Fangio chetti, Mariana González, Maxi- 8 Maserati Race Cars Driven By Fangio miliano Manzón, Nancy Segovia, Mariana López. Diseño y diagramación: Cynthia Aniversario Fundación J.M. Fangio Larocca 16 Fangio museum’s Anniverasry Fotografía: Matías González 100 años de Maserati Archivo fotográfico: Fundación Museo Juan Manuel Fangio 18 100 years of Maserati Traducción: Romina Molachino Destinos: Modena Corrección: Laura González 26 Destinations: Modena Impresión: Ediciones Emede S.A. -

Alo-Decals-Availability-And-Prices-2020-06-1.Pdf

https://alodecals.wordpress.com/ Contact and orders: [email protected] Availability and prices, as of June 1st, 2020 Disponibilité et prix, au 1er juin 2020 N.B. Indicated prices do not include shipping and handling (see below for details). All prices are for 1/43 decal sets; contact us for other scales. Our catalogue is normally updated every month. The latest copy can be downloaded at https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. N.B. Les prix indiqués n’incluent pas les frais de port (voir ci-dessous pour les détails). Ils sont applicables à des jeux de décalcomanies à l’échelle 1:43 ; nous contacter pour toute autre échelle. Notre catalogue est normalement mis à jour chaque mois. La plus récente copie peut être téléchargée à l’adresse https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. Shipping and handling as of July 15, 2019 Frais de port au 15 juillet 2019 1 to 3 sets / 1 à 3 jeux 4,90 € 4 to 9 sets / 4 à 9 jeux 7,90 € 10 to 16 sets / 10 à 16 jeux 12,90 € 17 sets and above / 17 jeux et plus Contact us / Nous consulter AC COBRA Ref. 08364010 1962 Riverside 3 Hours #98 Krause 4.99€ Ref. 06206010 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #50 Miles 5.99€ Ref. 06206020 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #54 Wietzes 5.99€ Ref. 08323010 1963 Nassau Trophy Race #49 Butler 3.99€ Ref. 06150030 1963 Sebring 12 Hours #11 Maggiacomo-Jopp 4.99€ Ref. 06124010 1964 Sebring 12 Hours #16 Noseda-Stevens 5.99€ Ref. 08311010 1965 Nürburgring 1000 Kms #52 Sparrow-McLaren 5.99€ Ref. -

Connecticut Yankee in the Court of Open Wheel Racing

NORTHEAST MOTORSPORTS JOURNAL Covering New England, New York and New Jersey Vol. 2 Issue 3 June 1992 Connecticut Yankee in the Court of Open Wheel Racing Motorsport’s Teams of the Northeast... Charlie McCarthy’s Chatim Racing Team - p. 27. Nascar comes to Lime Rock in August - p. 17 Modifieds rule at Seekonk & Thompson - p. 12 Vol. 2 Issue 3 MOTORSPORTS TEAMS OF THE NORTHEAST Last month we interviewed Bob Akin, longtime Porsche racer and winner of the Sebring 12 hour race at his racing complex in New York.We are continuing with our in depth and personal series on the Motorsport's Teams of the Northeast. In this issue we are talking with Charlie McCarthy, owner of the Chatim Racing Team based out of Warwick, RI. Chatim's race shop is a 10,000 sq ft building located in a light industrial area park right off Route 95, just 10 minutes from the state airport. The team has a full time staff of 10 people divided between office involved in the businesses. He was one of our main drivers and shop. In addition to maintaining the race cars, Chatim also and would fly in for the races or testing and then back to offers for sale a street conversion of customers Camaros and school. Now he wants to concentrate all his efforts on the Firebirds to 1LE race specs. Basically, they take your street car business, so he won't be driving at all this season. and make it a race car,tires, brakes, engine mods and suspension while keeping it street legal. -

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

The Porsche Collection Phillip Island Classic PORSCHES GREATEST HITS PLAY AGAIN by Michael Browning

The Formula 1 Porsche displayed an interesting disc brake design and pioneering cooling fan placed horizontally above its air-cooled boxer engine. Dan Gurney won the 1962 GP of France and the Solitude Race. Thereafter the firm withdrew from Grand Prix racing. The Porsche Collection Phillip Island Classic PORSCHES GREATEST HITS PLAY AGAIN By Michael Browning Rouen, France July 8th 1962: It might have been a German car with an American driver, but the big French crowd But that was not the end of Porsche’s 1969 was on its feet applauding as the sleek race glory, for by the end of the year the silver Porsche with Dan Gurney driving 908 had brought the marque its first World took the chequered flag, giving the famous Championship of Makes, with notable wins sports car maker’s new naturally-aspirated at Brands Hatch, the Nurburgring and eight cylinder 1.5 litre F1 car its first Grand Watkins Glen. Prix win in only its fourth start. The Type 550 Spyder, first shown to the public in 1953 with a flat, tubular frame and four-cylinder, four- camshaft engine, opened the era of thoroughbred sports cars at Porsche. In the hands of enthusiastic factory and private sports car drivers and with ongoing development, the 550 Spyder continued to offer competitive advantage until 1957. With this vehicle Hans Hermann won the 1500 cc category of the 3388 km-long Race “Carrera Panamericana” in Mexico 1954. And it was hardly a hollow victory, with The following year, Porsche did it all again, the Porsche a lap clear of such luminaries this time finishing 1st, 2nd, 4th and 5th in as Tony Maggs’ and Jim Clark’s Lotuses, the Targa Florio with its evolutionary 908/03 Graham Hill’s BRM. -

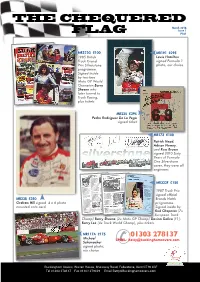

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

The Last Road Race

The Last Road Race ‘A very human story - and a good yarn too - that comes to life with interviews with the surviving drivers’ Observer X RICHARD W ILLIAMS Richard Williams is the chief sports writer for the Guardian and the bestselling author of The Death o f Ayrton Senna and Enzo Ferrari: A Life. By Richard Williams The Last Road Race The Death of Ayrton Senna Racers Enzo Ferrari: A Life The View from the High Board THE LAST ROAD RACE THE 1957 PESCARA GRAND PRIX Richard Williams Photographs by Bernard Cahier A PHOENIX PAPERBACK First published in Great Britain in 2004 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson This paperback edition published in 2005 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books Ltd, Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin's Lane, London WC2H 9EA 10 987654321 Copyright © 2004 Richard Williams The right of Richard Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 75381 851 5 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives, pic www.orionbooks.co.uk Contents 1 Arriving 1 2 History 11 3 Moss 24 4 The Road 36 5 Brooks 44 6 Red 58 7 Green 75 8 Salvadori 88 9 Practice 100 10 The Race 107 11 Home 121 12 Then 131 The Entry 137 The Starting Grid 138 The Results 139 Published Sources 140 Acknowledgements 142 Index 143 'I thought it was fantastic. -

20 7584 7403 E-Mail [email protected] 1958 Brm Type 25

14 QUEENS GATE PLACE MEWS, LONDON, SW7 5BQ PHONE +44 (0)20 7584 3503 FAX +44 (0)20 7584 7403 E-MAIL [email protected] 1958 BRM TYPE 25 Chassis Number: 258 Described by Sir Stirling Moss as the ‘best-handling and most competitive front-engined Grand Prix car that I ever had the privilege of driving’, the BRM P25 nally gave the British Formula One cognoscenti a rst glimpse of British single seater victory with this very car. The fact that 258 remains at all as the sole surviving example of a P25 is something to be celebrated indeed. Like the ten other factory team cars that were to be dismantled to free up components for the new rear-engined Project 48s in the winter of 1959, 258 was only saved thanks to a directive from BRM head oce in Staordshire on the express wishes of long term patron and Chairman, Sir Alfred Owen who ordered, ‘ensure that you save the Dutch Grand Prix winner’. Founded in 1945, as an all-British industrial cooperative aimed at achieving global recognition through success in grand prix racing, BRM (British Racing Motors) unleashed its rst Project 15 cars in 1949. Although the company struggled with production and development issues, the BRMs showed huge potential and power, embarrassing the competition on occasion. The project was sold in 1952, when the technical regulations for the World Championship changed. Requiring a new 2.5 litre unsupercharged power unit, BRM - now owned by the Owen Organisation -developed a very simple, light, ingenious and potent 4-cylinder engine known as Project 25. -

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

Mclaren AUTOMOTIVE STRENGTHENS GLOBAL COMMUNICATIONS TEAM with the APPOINTMENT of NEW HEAD of PR

Media Information EMBARGOED: 13:46.BST, 22 May 2012 McLAREN AUTOMOTIVE STRENGTHENS GLOBAL COMMUNICATIONS TEAM WITH THE APPOINTMENT OF NEW HEAD OF PR McLaren Automotive has appointed Wayne Bruce to the position of Head of Public Relations, with ultimate responsibility for the company’s global automotive PR strategy incorporating all brand and product matters. The move is effective immediately. Bruce joins McLaren Automotive with more than 15 years’ Public Relations and Communications experience, most recently at Nissan’s luxury brand, Infiniti, where he was responsible for establishing its Communications function across Europe. Previously he also worked for Nissan, SEAT and Volkswagen. Prior to working in PR, Bruce was an automotive journalist with UK based CAR magazine. He will report to McLaren Automotive’s Sales and Marketing Director, Greg Levine, and also to McLaren Marketing’s Group Head of Communications and PR, Matt Bishop. Commenting on the appointment, Levine said: “I am so excited to have Wayne on board particularly at this time when McLaren Automotive is about to embark on a period of growth through the launch of new products and new markets. He brings with him not just the respect of the industry but also a wealth of relevant experience and knowledge. Wayne is a petrolhead, too, a vital qualification for working at McLaren Automotive.” In reply, Bruce said: “I have been watching the launch of the MP4-12C from the outside and to be invited to join the team who have already achieved so much was an opportunity that I couldn’t refuse. Especially at this point in time when McLaren Automotive is entering the next chapter in its exciting story.” Bruce succeeds Mark Harrison, who recently took the post of Regional Director for McLaren Automotive Middle East and Africa, and will be located at the McLaren Technology Centre in Southern England. -

Metal Memory Excerpt.Pdf

In concept, this book started life as a Provenance. As such, it set about to verify the date, location and driver history of the sixth Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa produced, serial number 0718. Many an automotive author has generously given of his time and ink to write about the many limited series competition cars to come from Maranello individually and as a whole. The 250 TR has been often and lovingly included. Much has been scholastic in its veracity, some, adding myth to the legend. After a year's investigation on 0718, and many more on Ferrari's operation, the author has here constructed a family photo album, with interwoven narrative. The narrative is the story that came forward from the author's investigation and richly illustrative interviews conducted into 0718 specifically. To provide a deeper insight into the 250 TR itself we delve into the engineering transformation within Maranello that resulted in the resurrection of the competition V-12 engine, the unique (to the firm at that point) chassis it was placed in, and a body design that gave visual signature to this 1958 customer sports racer. From these elements was composed the publication you now hold. It is the Provenance of a Ferrari, that became the telling of a fifty-year-old mystery, red herrings and all. Table of Contents PROLOGUE 10 CHAPTER TEN TIME CAPSULE 116 CHAPTER ONE THERE IT WAS AGAIN 14 1959 VACA VALLEY GRAND PRIX 135 CHAPTER TWO TRS & MEXICO AT THE TIME 19 CHAPTER ELEVEN RAPIDLY, THROUGH THE CALIFORNIA LANDSCAPE 148 1959 RIVERSIDE GP FOR SPORTSCARS 26 1961 SACRAMENTO -

The Mexican Grand Prix 1963-70

2015 MEXICAN GRAND PRIX • MEDIA GUIDE 03 WELCOME MESSAGE 04 MEDIA ACCREDITATION CENTRE AND MEDIA CENTRE Location Maps Opening Hours 06 MEDIA CENTRE Key Staff Facilities (IT • Photographic • Telecoms) Working in the Media Centre 09 PRESS CONFERENCE SCHEDULE 10 PHOTOGRAPHERS’ SHUTTLE BUS SCHEDULE 11 RACE TIMETABLE 15 USEFUL INFORMATION Airline numbers Rental car numbers Taxi companies 16 MAPS AND DIAGRAMS Circuit with Media Centre Media Centre layout Circuit with corner numbers Photo positions map Hotel Maps 22 2015 FIA FORMULA ONE™ WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP Entry List Calendar Standings after round 16 (USA) (Drivers) Standings after round 16 (USA) (Constructors) Team & driver statistics (after USA) 33 HOW IT ALL STARTED 35 MEXICAN DRIVERS IN THE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP 39 MÉXICO IN WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP CONTEXT 40 2015 SUPPORT RACES 42 BACKGROUNDERS BIENVENIDO A MÉXICO! It is a pleasure to welcome you all to México as we celebrate our country’s return to the FIA Formula 1 World Championship calendar. Twice before, from 1963 to 1970 and from 1986 to 1992, México City has been the scene of exciting World Championship races. We enjoy a proud heritage in the sport: from the early brilliance of the Rodríguez brothers, the sterling efforts of Moisés Solana and Héctor Rebaque to the modern achievements of Esteban Gutíerrez and Sergio Pérez, Mexican drivers have carved their own names in the history of the sport. A few of you may have been here before. You will find many things the same – yet different. The race will still take place in the parkland of Magdalena Mixhuca where great names of the past wrote their own page in Mexican history, but the lay-out of the 21st-century track is brand-new.