The Beef Cattle Industry in the Roraima Savannas a Potential Supply for Brazil's North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Features and Conservation of the Brazilian Pantanal Wetland

Wetlands Ecology and Management 12: 547–552, 2004. 547 # 2004 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Features and conservation of the Brazilian Pantanal wetland Arnildo Pott* and Vali Joana Pott Embrapa, Caixa postal 154, Campo Grande, MS, 79002-970 Brazil; *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted in revised form 18 July 2003 Key words: Aquatic vegetation, Ecology, Floodable grassland, Neotropical wetland, Savanna, Vegetation dynamics Abstract The Pantanal is a 140,000 km2 sedimentary floodplain in western Brazil and one of the largest wetlands in the world. The main landscapes and phytophysiognomies, according to flood origin, are briefly described and some of the characteristic plant species are mentioned: (a) river flood (1–5 m) on clayey eutrophic soils with gallery forests, pioneer forests and scrub, Tabebuia and Copernicia parks, seasonal swamps, grasslands and oxbow lakes; and (b) rain flood (10–80 cm) mainly on dystrophic sandy soils (72% of the total area) with savanna (‘‘cerrado’’) grasslands and woodlands, with or without ponds. Regulating factors of the vegetation such as wet-and-dry cycle and management are considered. Dynamics of the vegetation, in particular the aquatic types, are shortly depicted. The role of grazing for conservation is discussed, and we suggest that 200 years of cattle ranching apparently did not cause major changes in the vegetation, except turning tall grass into short swards, as the domestic herd found a nearly empty niche. However, severe threats to the flora and fauna of the Pantanal originate outside the floodplain. Siltation of the Taquari river is pointed out as the worst environmental problem, changing the hydrology (wet-and-dry to wet), fauna and flora, e.g. -

CERRADO BIOME an Assessment Developed for the Climate and Land Use Alliance by CEA Consulting August 2016 MAP 1: BRAZIL’S CERRADO BIOME

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR CONSERVATION, AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION, AND SOCIAL INCLUSION IN THE CERRADO BIOME An assessment developed for the Climate and Land Use Alliance by CEA Consulting August 2016 MAP 1: BRAZIL’S CERRADO BIOME AREA OF DETAIL Brazil Sources: Reference layers: http://www.naturalearthdata.com/ Matopiba: http://www.ibge.gov.br/english/geociencias/default_prod.shtm Cerrado Biome: http://maps.lapig.iesa.ufg.br/lapig.html Photo: CEA CONTENTS About this report 2 Executive summary 3 Introduction 13 Proposed priorities 18 PRIORITY 1 Strong implementation of the Forest Code 18 PRIORITY 2 Protection and management of community and conservation lands 26 PRIORITY 3 Incentives for conservation 36 PRIORITY 4 Improved sustainability and productivity of existing agricultural lands and pasturelands 40 PRIORITY 5 Cover photos: Building the case for biodiversity ponsulak/Shutterstock (soybeans) Bento Viana/ISPN (palm and cut fruit) and landscape conservation 46 Paulo Vilela/Shutterstock (soy plants) Peter Caton/ISPN (baskets) Research agenda 49 Alf Ribeiro/Shutterstock (tractors) Conclusion 51 ABOUT THIS REPORT This document outlines a set of opportunities that can contribute to conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems, growth in agricultural production, and support for social inclusion and traditional livelihoods in Brazil’s Cerrado biome for the future of the region. It was prepared by CEA Consulting at the request of the Climate and Land Use Alliance (CLUA), a philanthropic collaborative of the ClimateWorks Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. It was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the ClimateWorks Foundation. The intended audience for this report is the full range of stakeholders working in the Cerrado biome; the recommendations included here are not designed for any particular actor and in fact would necessarily need to be undertaken by many different actors. -

Safeguarding the Pantanal Wetlands: Threats and Conservation Initiatives

Safeguarding the Pantanal Wetlands: Threats and Conservation Initiatives MONICAˆ B. HARRIS,∗†† WALFRIDO TOMAS,† GUILHERME MOURAO,†˜ CAROLINA J. DA SILVA,‡ ERIKA GUIMARAES,˜ ∗ FATIMA´ SONODA,§ AND ELIANI FACHIM§ ∗Conserva¸c˜ao Internacional–Brasil, Rua Paran´a 32, Campo Grande 79021–220, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil †Embrapa Pantanal, Rua 21 de Setembro 1880, Bairro Nossa Senhora de F´atima, Caixa Postal 109, Corumb´a 79320–900, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil ‡Departamento de Botˆanica e Ecologia, Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso, Avenida Tancredo Neves 1095, Cavalhada, C´aceres 78200–000, Mato Grosso, Brasil §ECOTROPICA,´ Rua 3, No. 391, Boa Esperan¸ca, Cuiab´a 78068–370, Mato Grosso, Brasil Abstract: ThePantanal, one of the largest wetlands on the planet, comprises 140,000 km2 of lowland flood- plain of the upper Rio Paraguai basin that drains the Cerrado of central Brazil. The diverse mosaics of habitats resulting from the varied soil types and inundation regimes are responsible for an extraordinarily rich terres- trial and aquatic biota, exemplified by the bird richest wetland in the world—463 birds have been recorded there—and the largest known populations of several threatened mammals, such as Pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus), marsh deer ( Blastocerus dichotomus), giant otter ( Pteronura brasiliensis), and jaguar ( Panthera onca). Until recently, deforestation of the adjoining Brazilian central plateau was considered the major threat to this area, but now deforestation is a critical problem within the floodplain itself. More than 40% of the forest and savanna habitats have been altered for cattle ranching through the introduction of exotic grasses. And there are other threats that lead to large-scale disruption of ecological processes, severely affecting biodi- versity. -

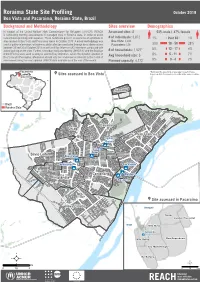

Roraima State Site Profiling. Boa Vista and Pacaraima, Roraima State

Roraima State Site Profiling October 2018 Boa Vista and Pacaraima, Roraima State, Brazil Background and Methodology Sites overview Demographics In support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), REACH Assessed sites: 8 53% male / 47% female 1+28+4+7+7 is conducting monthly assessments in managed sites in Roraima state, in order to assist 1+30+5+8+9 humanitarian planning and response. These factsheets present an overview of conditions in # of individuals: 3,872 1% 0ver 60 1% sites located in Boa Vista and Pacaraima towns in October 2018. A mixed methodology was Boa Vista: 3,444 used to gather information, with primary data collection conducted through direct observations Pacaraima: 428 30% 18 - 59 28% between 29 and 30 of October 2018 as well as 8 Key Informant (KI) interviews conducted with 5% 12 - 17 4% actors working on the sites. Further, secondary data provided by UNHCR KI and the Brazilian # of households: 1,527* Armed Forces were used to analyse selected key indicators. Given the dynamic situation in Avg household size: 3 8% 5 - 11 7% Boa Vista and Pacaraima, information should only be considered as relevant to the month of assessment using the most updated UNHCR data available as of the end of the month. Planned capacity: 4,172 9% 0 - 4 7% !(Pacaraima *Estimated by assuming an average household size, !( ¥Sites assessed in Boa Vista based on data from previous rounds in the same location. Boa Vista Cauamé Brazil Roraima State Cauamé União São Francisco Jardim Floresta ÔÆ Tancredo Neves Silvio Leite Nova Canaã ÔÆ ÔÆ Pintolândia São Vicente ÔÆ ÔÆ ÔÆ Centenário ÔÆ Rondon 1 Pintolândia Rondon 3 ¥Site assessed in Pacaraima Nova Cidade Venezuela Suapi Jardim Florestal Brazil Vila Nova Janokoida ÔÆ Das Orquídeas Vila Velha Ilzo Montenegro Da Balança ² ² km m 0 1,5 3 0 500 1.000 Fundo de População das Nações Unidas União Europeia Roraima site profiling October 2018 Jardim Floresta Boa Vista, Roraima State, Brazil Lat. -

The Relevance of the Cerrado's Water

THE RELEVANCE OF THE CERRADO’S WATER RESOURCES TO THE BRAZILIAN DEVELOPMENT Jorge Enoch Furquim Werneck Lima1; Euzebio Medrado da Silva1; Eduardo Cyrino Oliveira-Filho1; Eder de Souza Martins1; Adriana Reatto1; Vinicius Bof Bufon1 1 Embrapa Cerrados, BR 020, km 18, Planaltina, Federal District, Brazil, 70670-305. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT: The Cerrado (Brazilian savanna) is the second largest Brazilian biome (204 million hectares) and due to its location in the Brazilian Central Plateau it plays an important role in terms of water production and distribution throughout the country. Eight of the twelve Brazilian hydrographic regions receive water from this Biome. It contributes to more than 90% of the discharge of the São Francisco River, 50% of the Paraná River, and 70% of the Tocantins River. Therefore, the Cerrado is a strategic region for the national hydropower sector, being responsible for more than 50% of the Brazilian hydroelectricity production. Furthermore, it has an outstanding relevance in the national agricultural scenery. Despite of the relatively abundance of water in most of the region, water conflicts are beginning to arise in some areas. The objective of this paper is to discuss the economical and ecological relevance of the water resources of the Cerrado. Key-words: Brazilian savanna; water management; water conflicts. INTRODUCTION The Cerrado is the second largest Brazilian biome in extension, with about 204 million hectares, occupying 24% of the national territory approximately. Its largest portion is located within the Brazilian Central Plateau which consists of higher altitude areas in the central part of the country. -

The Cerrado-Pantanal Biodiversity Corridor in Brazil

The Cerrado-Pantanal Biodiversity Corridor in Brazil Pantanal Program Mônica Harris, Erika Guimarães, George Camargo, Cláudia Arcângelo, Elaine Pinto Cerrado Program Ricardo Machado, Mario Barroso, Cristiano Nogueira CI in Brazil • Active since 1988. • Two Hotspots: Atlantic Forest and Cerrado • Three Wilderness Areas: Amazon, Pantanal and Caatinga • Marine Program Cerrado overview • 2,000,000 km2 Savannah • approximately 4,400 of its 10,000 plant species occur nowhere else in the world • 75% loss of the original vegetation cover • Waters from the Cerrado drain into the lower Pantanal Pantanal overview • A 140,000 km2 central floodplain surrounded by a highland belt of Cerrado • Home for at least: – 3,500 species of plants –300fishes –652 birds –102 mammals – 177 reptiles – 40 amphibians • Largest wetland in the world, with extremely high densities of several large vertebrate species The Cerrado – Pantanal Biodiversity Corridor – The Beginning: • Priority Setting Workshop for the Cerrado and the Pantanal (1998) • Partnership:CI, Ministry for the Environment, Funatura, Biodiversitas and UnB. • Priority areas were identified for biodiversity conservation by 250 specialists TheThe ResultsResults:: Priority Areas for the Conservation of the Cerrado and Pantanal Corredores de Biodiversidade Cerrado / Pantanal CorridorsCorridors Chapada dos Guimarães betweenbetween # # thethe CerradoCerrado # Unidade de conservação Pantanal Matogrossense andand thethe Áreas prioritárias Taquaril Emas Rios # Corredores propostos PantanalPantanal Pantanal Rio -

Exploratory Temporal and Spatial Distribution Analysis of Dengue Notifications in Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazilian Amazon, 1999-2001†

Exploratory Temporal and Spatial Distribution Analysis of Dengue Notifications in Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazilian Amazon, 1999-2001† by Maria Goreti Rosa-Freitas*, Pantelis Tsouris**#, Alexander Sibajev***, Ellem Tatiani de Souza Weimann**, Alexandre Ubirajara Marques**, Rodrigo Lopes Ferreira** and José Francisco Luitgards-Moura*** *Laboratório de Transmissores de Hematozoários, Departamento de Entomologia, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Av. Brasil 4365, Manguinhos, 21045-900 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil **Núcleo Avançado de Vetores – Convênio FIOCRUZ-UFRR BR 174 S/N - Boa Vista, RR, Brasil ***Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, UFRR, BR 174 S/N - Boa Vista, RR, Brasil Abstract In Brazil, as in the rest of the world, dengue has become the most important arthropod-borne viral disease of public health significance. Roraima state presented the highest dengue incidence coefficient in Brazil in the last few years (224.9 and 164.2 per 10,000 inhabitants in 2000 and 2001, respectively). The capital, Boa Vista, reports the highest number of dengue cases in Roraima. This study examined the temporal and spatial distribution of dengue in Boa Vista during the years 1999- 2001, based on daily notifications as recorded by local health authorities. Temporally, dengue notifications were analysed by weekly and monthly averages and age distribution and correlated to meteorological variables. Spatially, dengue coefficients, premises infestation indices, population density and income levels were allocated in a geographical information system using, Boa Vista 49 neighbourhoods as units. Dengue outbreaks displayed distinct year-to-year distribution patterns that were neither periodical nor significantly correlated to any meteorological variable. There were no preferences for age and sex. -

Um Estudo Sobre Amapá E Roraima

ISSN 1415-4765 TEXTO PARA DISCUSSÃO NO 683 Federalismo, Repasses Federais e Crescimento Econômico: um Estudo sobre Amapá e Roraima Bruno de Oliveira Cruz Carlos Wagner de Albuquerque Oliveira Brasília, novembro de 1999 ISSN 1415-4765 TEXTO PARA DISCUSSÃO NO 683 Federalismo, Repasses Federais e Crescimento Econômico: um Estudo sobre Amapá e Roraima* Bruno de Oliveira Cruz** Carlos Wagner de Albuquerque Oliveira** Brasília, novembro de 1999 * Os autores agradecem a Mônica Mora, Antônio Carlos Galvão, Herton Araújo, Nelson Zackseski, Maria Cris- tina Macdowell, Luciana Mendes, Salvador Viana e Humberto Watson pelos comentários, sugestões e auxílio para o término desta pesquisa. ** Pesquisadores da Diretoria de Políticas Regionais e Urbanas do IPEA. MINISTÉRIO DO PLANEJAMENTO, ORÇAMENTO E GESTÃO Martus Tavares – Ministro Guilherme Dias – Secretário Executivo Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada Presidente Roberto Borges Martins DIRETORIA Eustáquio J. Reis Gustavo Maia Gomes Hubimaier Cantuária Santiago Luís Fernando Tironi Murilo Lôbo Ricardo Paes de Barros Fundação pública vinculada ao Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão, o IPEA fornece suporte técnico e institucional às ações governamentais e torna disponíves, para a sociedade, elementos necessários ao conhecimento e à solução dos problemas econômicos e sociais do país. Inúmeras políticas públicas e programas de desenvolvimento brasileiro são formulados a partir dos estudos e pesquisas realizados pelas equipes de especialistas do IPEA. TEXTO PARA DISCUSSÃO tem o objetivo de divulgar resultados de estudos desenvolvidos direta ou indiretamente pelo IPEA, bem como trabalhos considerados de relevância para disseminação pelo Instituto, para informar profissionais especializados e colher sugestões. Tiragem: 115 exemplares COORDENAÇÃO DO EDITORIAL Brasília – DF: SBS Q. 1, Bl. -

Apostila De Geografia Do Maranhão Para Concursos E Vestibulares

www.castrodigital.com.br APOSTILAS OPÇÃO A Sua Melhor Opção em Concursos Públicos GEOGRAFIA DO MARANHÃO Localização do Estado do Maranhão: superfície; limites; linhas de fronteira; pontos extremos; Áreas de Proteção Ambiental (APA). Parques nacionais. Climas do Maranhão: pluviosidade e temperatura. Geomorfologia: classificação do relevo maranhense: planaltos, planícies e baixadas. Características dos rios maranhenses: bacias dos rios limítrofes: bacia do Pamaíba, do Gurupi e do Tocantins-Araguaia. Bacias dos rios genuinamente maranhenses. Principais Formações Vegetais: floresta, cerrado e cocais. Geografia da População: população absoluta; densidade demográfica; povoamento; movimentos populacionais. A agricultura maranhense: caracterização e principais produtos agrícolas; caracterização da Pecuária. Extrativismo: vegetal, animal e mineral. Parque industrial: indústrias de base e indústrias de transformação. Setor Terciário: comércio, telecomunicações, transportes. Malha viária. Portos e aeroportos. Localização do Estado do Maranhão: superfície; limites; linhas de fronteira; pontos extremos; Áreas de Proteção Ambiental (APA). Parques nacionais. Climas do Maranhão: pluviosidade e temperatura. Geomorfologia: classificação do relevo maranhense: planal- tos, planícies e baixadas. Características dos rios maranhenses: bacias dos rios limítrofes: bacia do Parnaíba, do Gurupi e do To- cantins-Araguaia. Bacias dos rios genuinamente maranhenses. Principais Formações Vegetais: floresta, cerrado e cocais. Geografia do Maranhão 1 A Opção Certa Para -

Soy and Cattle: Report 7

Report 7 November 2019 1 Executive Summary This report presents 12 cases of land clearing based on alerts data from DETER (System for Monitoring Deforestation on Real Time) and PRODES (Program for Deforestation Calculation) observed between 27 August 2019 and 26 September 2019, in the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado biomes. Land clearing alerts considered in this report were visually confirmed. Eight of the selected cases are in the Amazon biome, and four are in the Cerrado biome. Cleared land per municipality of all cases included in this report (in hectares) Canabrava do Norte (Mato Grosso) Cumaru do Norte (Pará) São Félix do Xingu (Pará) Paranatinga (Mato Grosso) Brasnorte (Mato Grosso) Peixoto de Azevedo (Mato Grosso) Formosa do Rio Preto (Bahia) Damianópolis (Goiás) Terminology Barreiras (Bahia) 0 2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000 10,000 Amazon (18,232 ha) Cerrado (4,685 ha) Rapid Response Soy & Cattle – Report 7 – November 2019 2 Table of Contents Amazon Biome 1. Fazenda Rio Preto I e II – Canabrava do Norte (Mato Grosso) .................... 4 2. Fazenda Rio Dourado – Cumaru do Norte (Pará) ........................................ 7 3. Fazenda Nossa Senhora da Medalha – São Félix do Xingu (Pará) ............... 10 4. Fazenda Cabocla – Cumaru do Norte (Pará) ................................................ 12 5. Fazenda Brusque do Xingu – São Félix do Xingu (Pará) …………………..….…… 15 6. Fazenda Macuco – Paranatinga (Mato Grosso) …………………………………..…… 18 7. Fazenda Nove de Julho – Brasnorte (Mato Grosso) ……………………………...… 20 8. Fazenda São José I – Peixoto de Azevedo (Mato Grosso) ………................…. 23 Cerrado Biome 9. Fazenda Santa Maria Gleba 02 and Fazenda Santa Maria Gleba 03 – Formosa do Rio Preto (Bahia) ……………………………………………………………………… 25 10. Fazenda Grotão – Damianópolis (Goiás) ……………………………………….………. -

Chapter 3 the North- Lost in the Amazon

BRAZIL Chapter 3 The North- Lost in the Amazon Have you ever heard about Amazon rainforest? Let us learn together! The equatorial North, also known as the Amazon or Amazônia, is Brazil's largest region with total landmass of 3,869,638 square kilometers, covering 45.3 percent of the national territory. Way too big and enormous!! It is also the least inhabited part of the country. 31 BRAZIL The region has the largest rainforest of the world and is called Amazon. The word Amazon refers to the women warriors who once fought in inter-tribe in ancient times in this region of today's North Region of Brazil. It is also the name of one of the major river that passes through Brazil and flows eastward into South Atlantic. This river is also the largest of the world in terms of water carried in it. There are also numerous other rivers in the area. It is one fifth of all the earth's fresh water reserves. There are two main Amazonian cities: Manaus, capital of the State of Amazonas, and Belém, capital of the State of Pará. 32 BRAZIL Over half of the Amazon rainforest( more than 60 per cent) is located in Brazil but it is also located in other South American countries including Peru, Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia, Guyana, Bolivia, Suriname and French Guiana. The Amazon is home to around two and a half million different insect species as well as over 40000 plant species. There are also a number of dangerous species living in the Amazon rainforest such as the “Onça Pintada” (Brazilian Puma) and anaconda. -

Ecotourism in the North Pantanal, Brazil: Regional Bases and Subjects for Sustainable Development

Geographical Review of Japan Vol. 78, No. 5, 289-310, 2005 Ecotourism in the North Pantanal, Brazil: Regional Bases and Subjects for Sustainable Development MARUYAMA Hiroaki*, NIHEI Takaaki**, and NI HIWAKI Yasuyukl* *Faculty of Education and Human Sciences, Yokohama National University, Yokohama 240-8501, Japan **Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8572, Japan Abstract: The Brazilian Pantanal, the world's largest wetland holding abundant wildlife, has recently drawn profound concern about the development of the tourist industry. To provide significant proposals for ecotourism in the wetland, we believe that detailed data acquired by fieldwork is requisite, This study examines the regional bases that carry regional ecotourism, and attempts to present some proposals for ecotourism from the case of the north Pantanal. The results are shown as follows in order of regional scale. (1) In the water source of the Pantanal, Cerrado region, it is necessary to make efficient plans to control recent agricultural development, especially in soybean and cotton production. (2) On the wetland level, legally protected areas such as national parks and RPPN (Reserva Particular do Patrimonio Natural) should be extended. (3) On the municipal level, environmental subsidies are needed for disused goldmines, and for the maintenance of tourist infrastructures such as Transpantaneira and MT 370. (4) Modern hotels and eco-lodges need to provide ecotourism organized by local people, and to equip the facilities with adequate sewage facilities and garbage recycle plants to preserve the natural environment. Key words: ecotourism, Transpantaneira, hotel, eco-lodge, Pantanal, Brazil ment1 that aims at coping with the fixation Introduction and indivisible quandaries of tourism in the late 1980s (Funck 2002).