The Hindu Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arvind Sharma, Advaita Vediinta. an Introduction, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2004, Pp

ISSN 1648-2662 ACTA ORIENTALIA VILNENSIA. 2004 5 Arvind Sharma, Advaita Vediinta. An Introduction, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2004, pp. vii+125. ISBN 81-208-2027-4, Rs 295.00 Reviewed by Kazimieras Seibutis Sri Aurobindo Cultural Center, Vilnius Any book about such a challenging matter as Advaita Vedanta is fascinating, therefore it is no wonder that reading a short introduction on the subject by Arvind Sharrna is an exciting experience indeed, not only because the author manages to avoid getting involved in conflicting aspects of different schools of classical intellectual trend of India that is not yet widely known in the West, but also because the subject matter is presented in a condensed and very succinct manner. Sharrna, Birks Professor of Comparative Religion at McGill University, attempts to over come this challenge by consistently relying on three approaches: scriptural, rational and experiential. Sharma says that he "tries to accord an independent status to each of these approaches without losing sight of their interconnectedness". In a short preface prior to the analysis, Sharma calls the readers' attention to a fundamental fact that in the West philosophy represents an intellectual movement which has achieved an independent status by shaking off constrains of theology. Meanwhile, within the framework of Indian culture such a divergence between philosophy and religion did not occur, and according to Sharma "the two, even when they become dual, remain undivided." Sharrna also draws attention to the concept of jfvanmukti and the pivotal idea, which supports the concept of jfvanmukti, that the results of one's faith can be attained while still living in this world. -

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Inseparable Faith: Exploring Manifestations and Experiences of Faith-Work Integration in Young Alumni from a Christian University Emilie Hoffman Taylor University

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University Master of Arts in Higher Education Thesis Collection 2017 Inseparable Faith: Exploring Manifestations and Experiences of Faith-Work Integration in Young Alumni from a Christian University Emilie Hoffman Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/mahe Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Hoffman, Emilie, "Inseparable Faith: Exploring Manifestations and Experiences of Faith-Work Integration in Young Alumni from a Christian University" (2017). Master of Arts in Higher Education Thesis Collection. 90. https://pillars.taylor.edu/mahe/90 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Higher Education Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INSEPARABLE FAITH: EXPLORING MANIFESTATIONS AND EXPERIENCES OF FAITH-WORK INTEGRATION IN YOUNG ALUMNI FROM A CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY _______________________ A thesis Presented to The School of Social Sciences, Education & Business Department of Higher Education and Student Development Taylor University Upland, Indiana ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Higher Education and Student Development _______________________ by Emilie Hoffman May 2017 Emilie Hoffman 2017 Higher Education and Student Development Taylor University Upland, Indiana CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL _________________________ MASTER’S THESIS _________________________ This is to certify that the Thesis of Emilie Hoffman entitled Inseparable Faith: Exploring Manifestations and Experiences of Faith-Work Integration in Young Alumni from a Christian University has been approved by the Examining Committee for the thesis requirement for the Master of Arts degree in Higher Education and Student Development May 2017 __________________________ _____________________________ Drew Moser, Ph.D. -

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

Hinduism Around the World

Hinduism Around the World Numbering approximately 1 billion in global followers, Hinduism is the third-largest religion in the world. Though more than 90 percent of Hindus live on the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bhutan), the Hindu diaspora’s impact can still be felt today. Hindus live on every continent, and there are three Hindu majority countries in the world: India, Nepal, and Mauritius. Hindu Diaspora Over Centuries Hinduism began in the Indian subcontinent and gradually spread east to what is now contemporary Southeast Asia. Ancient Hindu cultures thrived as far as Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Some of the architectural works (including the famous Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia) still remain as vestiges of Hindu contact. Hinduism in Southeast Asia co-worshipped with Buddhism for centuries. However, over time, Buddhism (and later Islam in countries such as Indonesia) gradually grew more prominent. By the 10th century, the practice of Hinduism in the region had waned, though its influence continued to be strong. To date, Southeast Asia has the two highest populations of native, non-Indic Hindus: the Balinese Hindus of Indonesia and the Cham people of Vietnam. The next major migration took place during the Colonial Period, when Hindus were often taken as indentured laborers to British and Dutch colonies. As a result, Hinduism spread to the West Indies, Fiji, Copyright 2014 Hindu American Foundation Malaysia, Mauritius, and South Africa, where Hindus had to adjust to local ways of life. Though the Hindu populations in many of these places declined over time, countries such as Guyana, Mauritius, and Trinidad & Tobago, still have significant Hindu populations. -

3. HINDUISM Chapter Overview According to the Time Line at The

3. HINDUISM Chapter Overview According to the time line at the back of this book, Hinduism is the oldest global religion. Pre- cursors of this Vedic faith may include some aspects of the Dravidians, advanced cultures of the Indus Valley, and the Harappans. A hotly contested scholarly reconstruction concludes that those called Aryans who were nomadic invaders from outside India eventually overran these highly organized cultures. Others though maintain that this religion is not foreign-born. Indian religion and philosophy have influenced many other religions and cultures. The country could be considered the birthplace of Eastern thought and practice. By pointing out to students that Hinduism provides ample opportunity to begin comparing and contrasting Eastern and Western forms of religious ways, they may better appreciate why it is the first global religion presented in the book. Indian religion combines the material and the spiritual in creative ways. There is something for everyone -- from the advocate of a strictly trained body to the quite philosophical thinker. India has room for all. The tolerance found in this culture of competing gods is refreshing, especially in today s world of tension and conflict when lives are lost over religious differences. This chapter seeks to achieve the following goals: 1. To outline the standard Western historical view of Hinduism s development and the Indian tradition of their history 2. To acquaint the reader with the major defining characteristics of this religion 3. To acquaint the reader with the spiritual practices of Hinduism, especially yoga and its different styles and purposes Draw the following on the board for a simple clarification of Hinduism: The Supreme God (Brahma) (Paramatma=The Supreme Soul) (Three primary roles) Brahama Vishnu/Krishna Shiva/Mahesh (Creator) (Protector) (Destroyer) Key concepts to explain: • Hinduism teaches the cycle of life: Birth---Life---Death---Rebirth. -

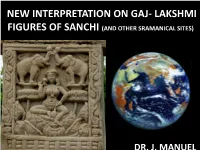

Female Deity of Sanchi on Lotus As Early Images of Bhu Devi J

NEW INTERPRETATION ON GAJ- LAKSHMI FIGURES OF SANCHI (AND OTHER SRAMANICAL SITES) nn DR. J. MANUEL THE BACK GROUND • INDRA RULED THE ROOST IN THE RGVEDIC AGE • OTHER GODS LIKE AGNI, SOMA, VARUN, SURYA BESIDES ASHVINIKUMARS, MARUTS WERE ALSO SPOKEN VERY HIGH IN THE LITERATURE • VISHNU IS ALSO KNOWN WITH INCREASING PROMINENCE SO MUCH SO IN THE LATE MANDALA 1 SUKT 22 A STRETCH OF SIX VERSES MENTION HIS POWER AND EFFECT • EVIDENTLY HIS GLORY WAS BEING FELT MORE AND MORE AS TIME PASSED • Mandal I Sukt 22 Richa 19 • Vishnu ki kripa say …….. Vishnu kay karyon ko dekho. Vay Indra kay upyukt sakha hai EVIDENTLY HIS GLORY WAS BEING FELT MORE AND MORE AS TIME PASSED AND HERO-GODS LIKE BALARAM AND VASUDEVA WERE ACCEPTED AS HIS INCARNATIONS • CHILAS IN PAKISTAN • AGATHOCLEUS COINS • TIKLA NEAR GWALIOR • ARE SOME EVIDENCE OF HERO-GODS BUT NOT VEDIC VISHNU IN SECOND CENTURY BC • There is the Kheri-Gujjar Figure also of the Therio anthropomorphic copper image BUT • FOR A LONG TIME INDRA CONTINUED TO HOLD THE FORT OF DOMINANCE • THIS IS SEEN IN EARLY SACRED LITERATURE AND ART ANTHROPOMORPHIC FIGURES • OF THE COPPER HOARD CULTURES ARE SAID TO BE INDRA FIGURES OF ABOUT 4000 YEARS OLD • THERE ARE MANY TENS OF FIGURES IN SRAMANICAL SITE OF INDRA INCLUDING AT SANCHI (MORE THAN 6) DATABLE TO 1ST CENTURY BCE • BUT NOT A SINGLE ONE OF VISHNU INDRA 5TH CENT. CE, SARNATH PARADOXICALLY • THERE ARE 100S OF REFERENCES OF VISHNU IN THE VEDAS AND EVEN MORE SO IN THE PURANIC PERIOD • WHILE THE REFERENCE OF LAKSHMI IS VERY FEW AND FAR IN BETWEEN • CURIOUSLY THE ART OF THE SUPPOSED LAXMI FIGURES ARE MANY TIMES MORE IN EARLY HISTORIC CONTEXT EVEN IN NON VAISHNAVA CONTEXT AND IN SUCH AREAS AS THE DECCAN AND AS SOUTH AS SRI- LANKA WHICH WAS THEN UNTOUCHED BY VAISHNAVISM NW INDIA TO SRI LANKA AZILISES COIN SHOWING GAJLAKSHMI IMAGERY 70-56 ADVENT OF VAISHNAVISM VISHNU HAD BY THE STARTING OF THE COMMON ERA BEGAN TO BECOME LARGER THAN INDRA BUT FOR THE BUDDHISTS INDRA CONTINUED TO BE DEPICTED IN RELATED STORIES CONTINUED FROM EARLIER TIMES; FROM BUDDHA. -

The World's Religions After September 11

The World’s Religions after September 11 This page intentionally left blank The World’s Religions after September 11 Volume 1 Religion, War, and Peace EDITED BY ARVIND SHARMA PRAEGER PERSPECTIVES Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The world’s religions after September 11 / edited by Arvind Sharma. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-275-99621-5 (set : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99623-9 (vol. 1 : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99625-3 (vol. 2 : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99627-7 (vol. 3 : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99629-1 (vol. 4 : alk. paper) 1. Religions. 2. War—Religious aspects. 3. Human rights—Religious aspects. 4. Religions—Rela- tions. 5. Spirituality. I. Sharma, Arvind. BL87.W66 2009 200—dc22 2008018572 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2009 by Arvind Sharma All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008018572 ISBN: 978-0-275-99621-5 (set) 978-0-275-99623-9 (vol. 1) 978-0-275-99625-3 (vol. 2) 978-0-275-99627-7 (vol. 3) 978-0-275-99629-1 (vol. 4) First published in 2009 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). -

Full Complaint

Case 1:18-cv-01612-CKK Document 11 Filed 11/17/18 Page 1 of 602 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ESTATE OF ROBERT P. HARTWICK, § HALEY RUSSELL, HANNAH § HARTWICK, LINDA K. HARTWICK, § ROBERT A. HARTWICK, SHARON § SCHINETHA STALLWORTH, § ANDREW JOHN LENZ, ARAGORN § THOR WOLD, CATHERINE S. WOLD, § CORY ROBERT HOWARD, DALE M. § HINKLEY, MARK HOWARD BEYERS, § DENISE BEYERS, EARL ANTHONY § MCCRACKEN, JASON THOMAS § WOODLIFF, JIMMY OWEKA OCHAN, § JOHN WILLIAM FUHRMAN, JOSHUA § CRUTCHER, LARRY CRUTCHER, § JOSHUA MITCHELL ROUNTREE, § LEIGH ROUNTREE, KADE L. § PLAINTIFFS’ HINKHOUSE, RICHARD HINKHOUSE, § SECOND AMENDED SUSAN HINKHOUSE, BRANDON § COMPLAINT HINKHOUSE, CHAD HINKHOUSE, § LISA HILL BAZAN, LATHAN HILL, § LAURENCE HILL, CATHLEEN HOLY, § Case No.: 1:18-cv-01612-CKK EDWARD PULIDO, KAREN PULIDO, § K.P., A MINOR CHILD, MANUEL § Hon. Colleen Kollar-Kotelly PULIDO, ANGELITA PULIDO § RIVERA, MANUEL “MANNIE” § PULIDO, YADIRA HOLMES, § MATTHEW WALKER GOWIN, § AMANDA LYNN GOWIN, SHAUN D. § GARRY, S.D., A MINOR CHILD, SUSAN § GARRY, ROBERT GARRY, PATRICK § GARRY, MEGHAN GARRY, BRIDGET § GARRY, GILBERT MATTHEW § BOYNTON, SOFIA T. BOYNTON, § BRIAN MICHAEL YORK, JESSE D. § CORTRIGHT, JOSEPH CORTRIGHT, § DIANA HOTALING, HANNA § CORTRIGHT, MICHAELA § CORTRIGHT, LEONDRAE DEMORRIS § RICE, ESTATE OF NICHOLAS § WILLIAM BAART BLOEM, ALCIDES § ALEXANDER BLOEM, DEBRA LEIGH § BLOEM, ALCIDES NICHOLAS § BLOEM, JR., VICTORIA LETHA § Case 1:18-cv-01612-CKK Document 11 Filed 11/17/18 Page 2 of 602 BLOEM, FLORENCE ELIZABETH § BLOEM, CATHERINE GRACE § BLOEM, SARA ANTONIA BLOEM, § RACHEL GABRIELA BLOEM, S.R.B., A § MINOR CHILD, CHRISTINA JEWEL § CHARLSON, JULIANA JOY SMITH, § RANDALL JOSEPH BENNETT, II, § STACEY DARRELL RICE, BRENT § JASON WALKER, LELAND WALKER, § SUSAN WALKER, BENJAMIN § WALKER, KYLE WALKER, GARY § WHITE, VANESSA WHITE, ROYETTA § WHITE, A.W., A MINOR CHILD, § CHRISTOPHER F. -

On Hindu, Hindustān, Hinduism and Hindutva Author(S): Arvind Sharma Source: Numen, Vol

On Hindu, Hindustān, Hinduism and Hindutva Author(s): Arvind Sharma Source: Numen, Vol. 49, No. 1, (2002), pp. 1-36 Published by: BRILL Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3270470 Accessed: 17/07/2008 09:39 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=bap. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org ON HINDU, HINDUSTAN, HINDUISM AND HINDUTVA ARVIND SHARMA Summary This paper sets out to examine the emergence and significanceof the word Hindu (and associatedterminology) in discourse about India, in orderto determinethe light it sheds on what is currently happening in India. -

History of Legalization of Abortion in the United States of America in Political and Religious Context and Its Media Presentation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at University of West Bohemia Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce History of legalization of abortion in the United States of America in political and religious context and its media presentation Klára Čížková Plzeň 2017 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra románských jazyků Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – francouzština Bakalářská práce History of legalization of abortion in the United States of America in political and religious context and its media presentation Klára Čížková Vedoucí práce: Ing. BcA. Milan Kohout Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2017 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2017 ……………………… Na tomto místě bych ráda poděkovala vedoucímu bakalářské práce Ing. BcA. Milanu Kohoutovi za cenné rady a odbornou pomoc, které mi při zpracování poskytl. Dále bych ráda poděkovala svému partnerovi a své rodině za podporu a trpělivost. Plzeň, duben 2017 ……………………… Table of contents 1 Introduction........................................................................................................1 2 History of abortion.............................................................................................3 2.1 19th Century.......................................................................................................3 -

(PPMG) Police Medal for Gallantry (PMG) President's

Force Wise/State Wise list of Medal awardees to the Police Personnel on the occasion of Republic Day 2020 Si. Name of States/ President's Police Medal President's Police Medal No. Organization Police Medal for Gallantry Police Medal (PM) for for Gallantry (PMG) (PPM) for Meritorious (PPMG) Distinguished Service Service 1 Andhra Pradesh 00 00 02 15 2 Arunachal Pradesh 00 00 01 02 3 Assam 00 00 01 12 4 Bihar 00 07 03 10 5 Chhattisgarh 00 08 01 09 6 Delhi 00 12 02 17 7 Goa 00 00 01 01 8 Gujarat 00 00 02 17 9 Haryana 00 00 02 12 10 Himachal Pradesh 00 00 01 04 11 Jammu & Kashmir 03 105 02 16 12 Jharkhand 00 33 01 12 13 Karnataka 00 00 00 19 14 Kerala 00 00 00 10 15 Madhya Pradesh 00 00 04 17 16 Maharashtra 00 10 04 40 17 Manipur 00 02 01 07 18 Meghalaya 00 00 01 02 19 Mizoram 00 00 01 03 20 Nagaland 00 00 01 03 21 Odisha 00 16 02 11 22 Punjab 00 04 02 16 23 Rajasthan 00 00 02 16 24 Sikkim 00 00 00 01 25 Tamil Nadu 00 00 03 21 26 Telangana 00 00 01 12 27 Tripura 00 00 01 06 28 Uttar Pradesh 00 00 06 72 29 Uttarakhand 00 00 01 06 30 West Bengal 00 00 02 20 UTs 31 Andaman & 00 00 00 03 Nicobar Islands 32 Chandigarh 00 00 00 01 33 Dadra & Nagar 00 00 00 01 Haveli 34 Daman & Diu 00 00 00 00 02 35 Puducherry 00 00 00 CAPFs/Other Organizations 13 36 Assam Rifles 00 00 01 46 37 BSF 00 09 05 24 38 CISF 00 00 03 39 CRPF 01 75 06 56 12 40 ITBP 00 00 03 04 41 NSG 00 00 00 11 42 SSB 00 04 03 21 43 CBI 00 00 07 44 IB (MHA) 00 00 08 23 04 45 SPG 00 00 01 02 46 BPR&D 00 01 47 NCRB 00 00 00 04 48 NIA 00 00 01 01 49 SPV NPA 01 04 50 NDRF 00 00 00 00 51 LNJN NICFS 00 00 00 00 52 MHA proper 00 00 01 15 53 M/o Railways 00 01 02 (RPF) Total 04 286 93 657 LIST OF AWARDEES OF PRESIDENT'S POLICE MEDAL FOR GALLANTRY ON THE OCCASION OF REPUBLIC DAY-2020 President's Police Medal for Gallantry (PPMG) JAMMU & KASHMIR S/SHRI Sl No Name Rank Medal Awarded 1 Abdul Jabbar, IPS SSP PPMG 2 Gh.